Nearly half say the pandemic has driven people in their community apart

Pew Research Center conducted this study to understand Americans’ views and preferences for where they live and the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on their local communities. For this analysis, we surveyed 9,676 U.S. adults in October 2021. Everyone who took part is a member of Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology.

See here to read more about the questions used for this report and the report’s methodology.

References to White, Black and Asian adults include only those who are not Hispanic and identify as only one race. Hispanics are of any race.

All references to party affiliation include those who lean toward that party. Republicans include those who identify as Republicans and those who say they lean toward the Republican Party. Democrats include those who identify as Democrats and those who say they lean toward the Democratic Party.

References to college graduates or people with a college degree comprise those with a bachelor’s degree or more. “Some college” includes those with an associate degree and those who attended college but did not obtain a degree.

“Middle income” is defined here as two-thirds to double the median annual family income for panelists on the American Trends Panel. “Lower income” falls below that range; “upper income” falls above it. See the methodology for more details.

References to respondents who live in urban, suburban or rural communities are based on respondents’ answer to the following question: “How would you describe the community where you currently live? (1) urban, (2) suburban, (3) rural.” Throughout the report, the terms “urban” and “city” are used interchangeably.

In the early days of the coronavirus outbreak, some wondered if city living would lose its appeal, especially as remote work gave people more freedom to choose where to live. About a year and a half into the pandemic, there is some evidence that Americans are less likely now than they were before to want to live in urban areas – and more likely to want to live in the suburbs, according to a new Pew Research Center survey.

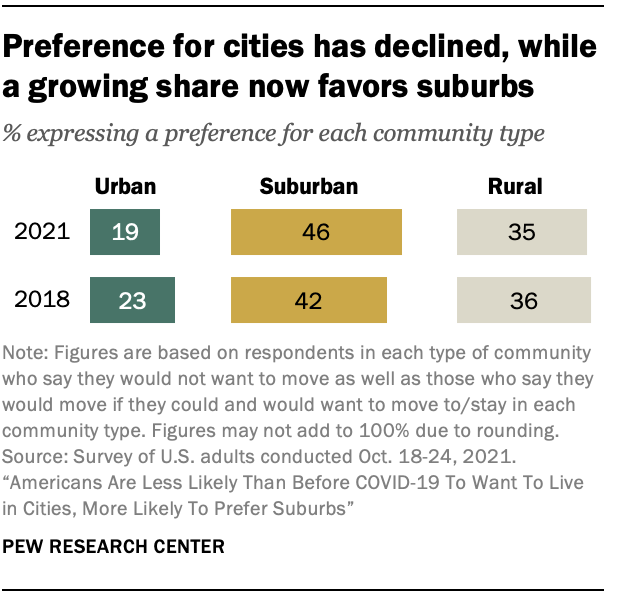

About one-in-five U.S. adults now express a preference for living in a city, down from about a quarter in 2018. The share of Americans who would like to live in the suburbs has increased from 42% to 46% during this time, while preference for rural areas is virtually unchanged.1

Related: In 2020, fewer Americans moved, exodus from cities slowed

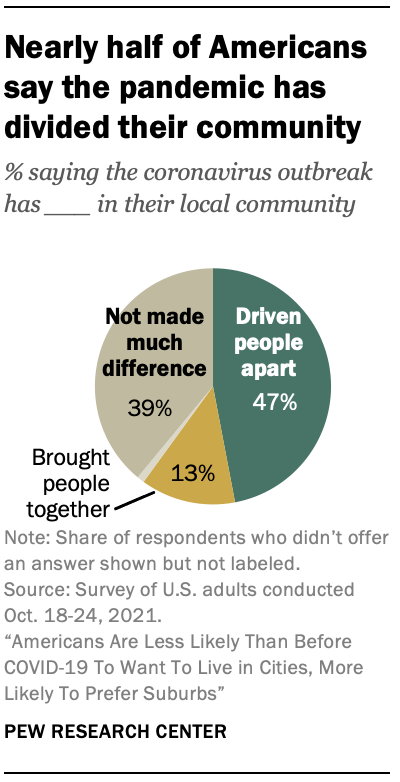

Regardless of where they live, nearly half of Americans (47% overall) say the pandemic has divided their communities; relatively few (13%) say it has brought people together. And many see a long road to recovery, with about one-in-five saying life in their community will never get back to the way it was before the coronavirus outbreak.

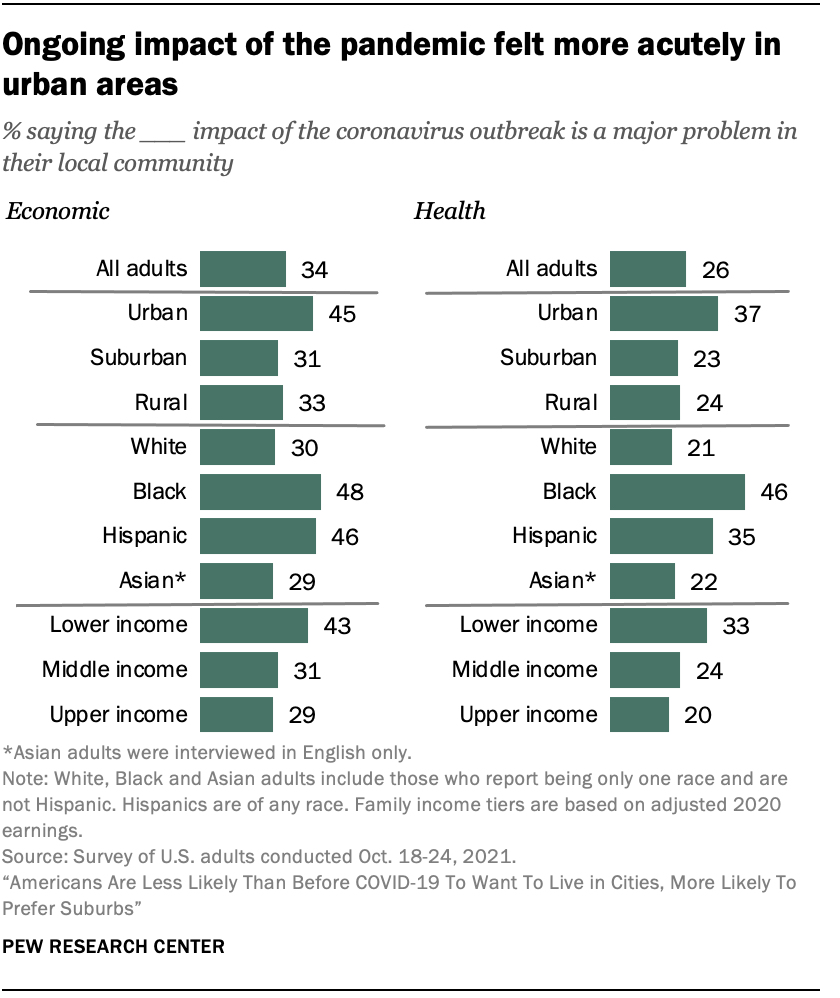

Across community types, about a quarter or more say the health and economic impacts of the pandemic remain major problems where they live, but the effects are felt most acutely in cities. More than four-in-ten urban residents (45%) say the economic impact of the outbreak is a major problem in their community, and 37% say the same about the health impact of COVID-19. By comparison, 31% of those in the suburbs and 33% of rural dwellers say the economic impact of the pandemic is a major problem in their local area, and about a quarter each say the health impact is a major issue.

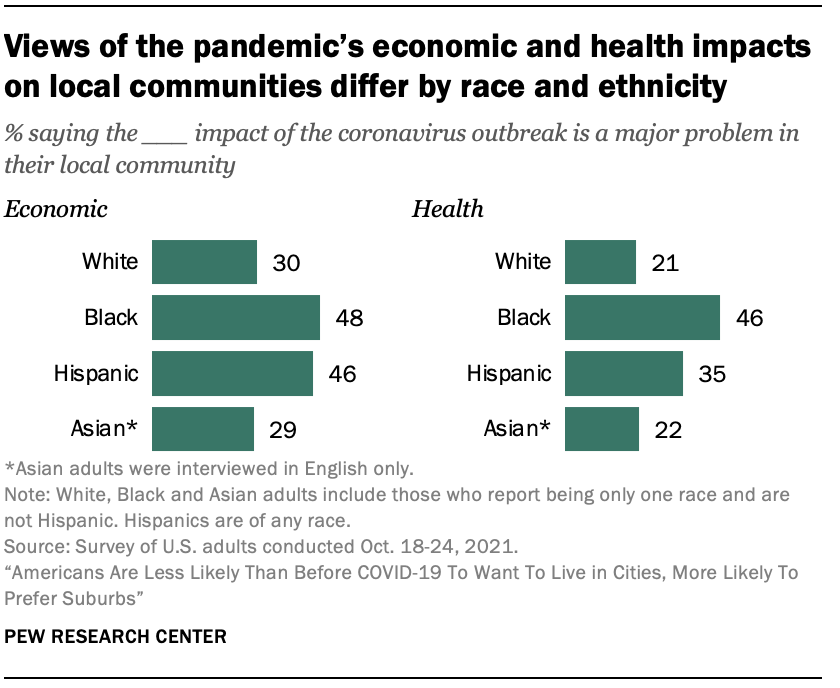

There are also racial, ethnic and income differences in these assessments. Black and Hispanic Americans are more likely than White or Asian Americans to say the pandemic’s economic impact is a major problem where they live, and Black adults are more likely than other racial or ethnic groups to say this about the health impact.2 Lower-income adults are also more likely than those with middle and upper incomes to say the health and economic impact of the pandemic are major problems in their local communities.3

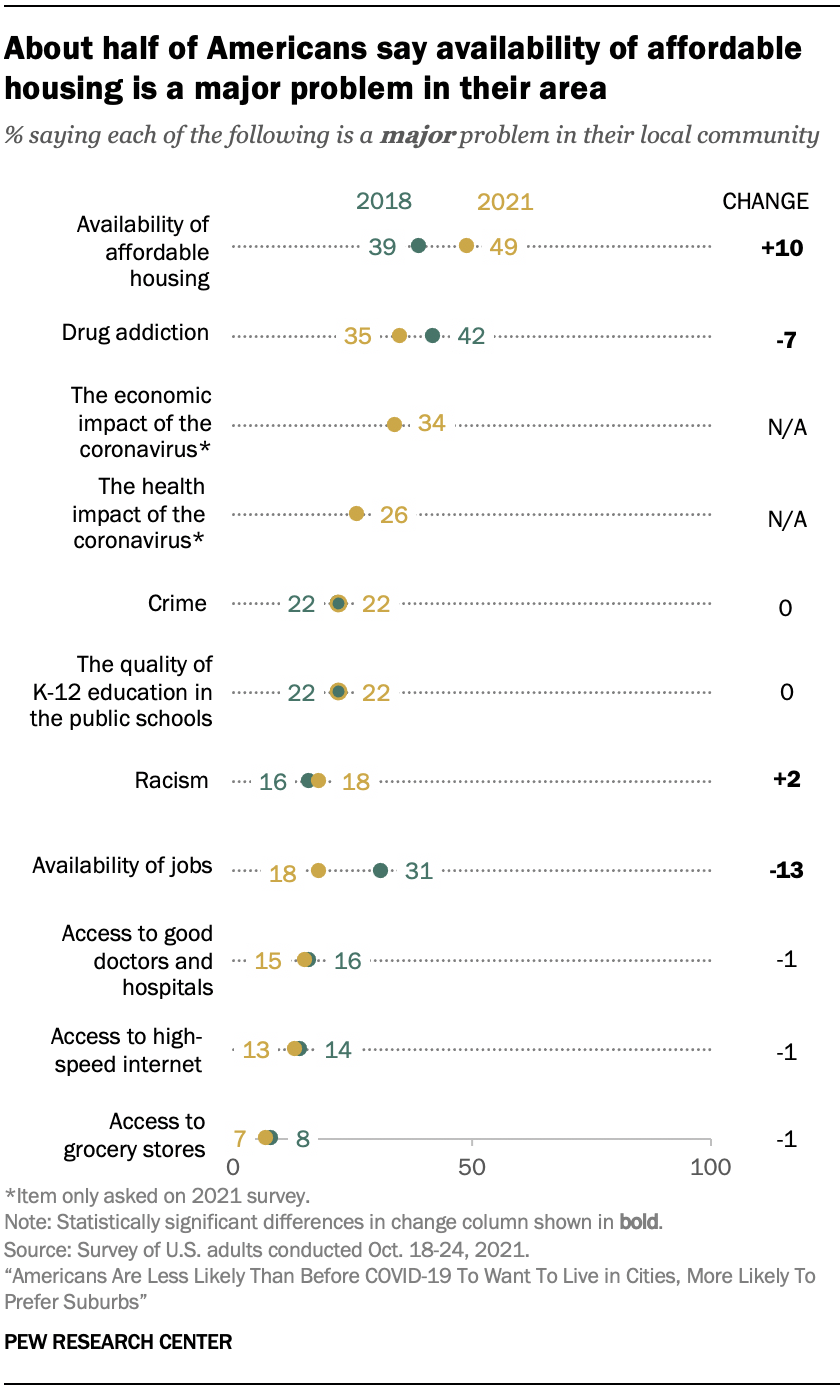

The pandemic isn’t the only issue Americans are facing in their local communities. About half of U.S. adults (49%) say the availability of affordable housing is a major problem where they live, up 10 percentage points from 2018.

At the same time, concern over drug addiction and the availability of jobs has waned. Some 35% now say drug addiction is a major problem in their community, down from 42% in 2018. And 18% say jobs are a major problem, down from 31%. About one-in-five say crime, the quality of K-12 schools and racism are major problems where they live – all relatively unchanged from 2018. With the exception of availability of jobs, urban residents are more likely than those in the suburbs or in rural areas to say each of the issues included in the survey is a major problem in their local community.

The nationally representative survey of 9,676 U.S. adults was conducted Oct. 18-24, 2021, before news of the omicron variant, using the Center’s American Trends Panel.4 Among the other key findings:

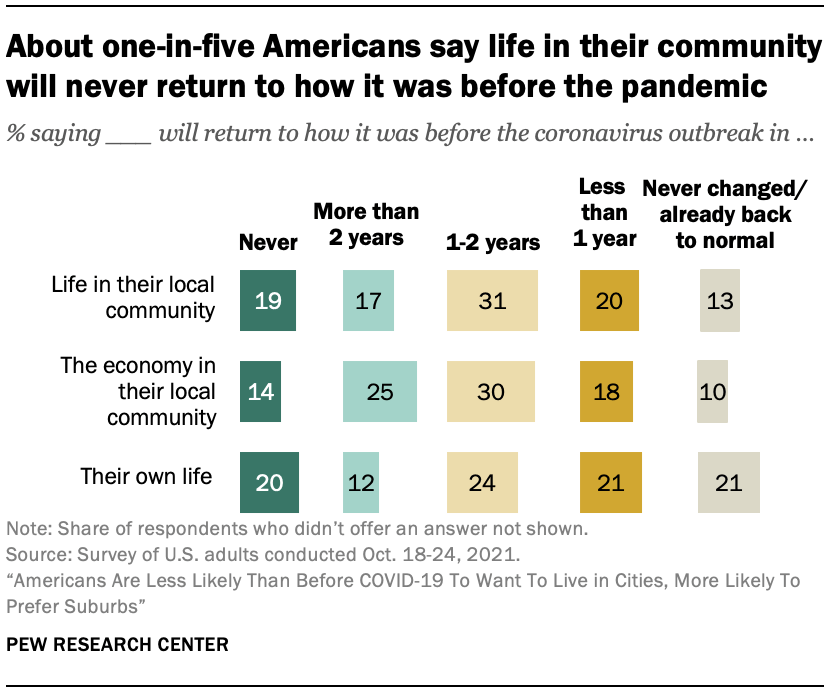

More than a third of U.S. adults (36%) say it will take over two years for their local community to return to how it was before the coronavirus outbreak or that their community will never get back to normal. An even higher share (39%) say this about the economy in their local community, including 14% who say their local economy will never come back. When asked about their own lives, about a third of adults say it will take more than two years for their life to return to how it was before the pandemic or that it will never be the same again (12% and 20%, respectively).

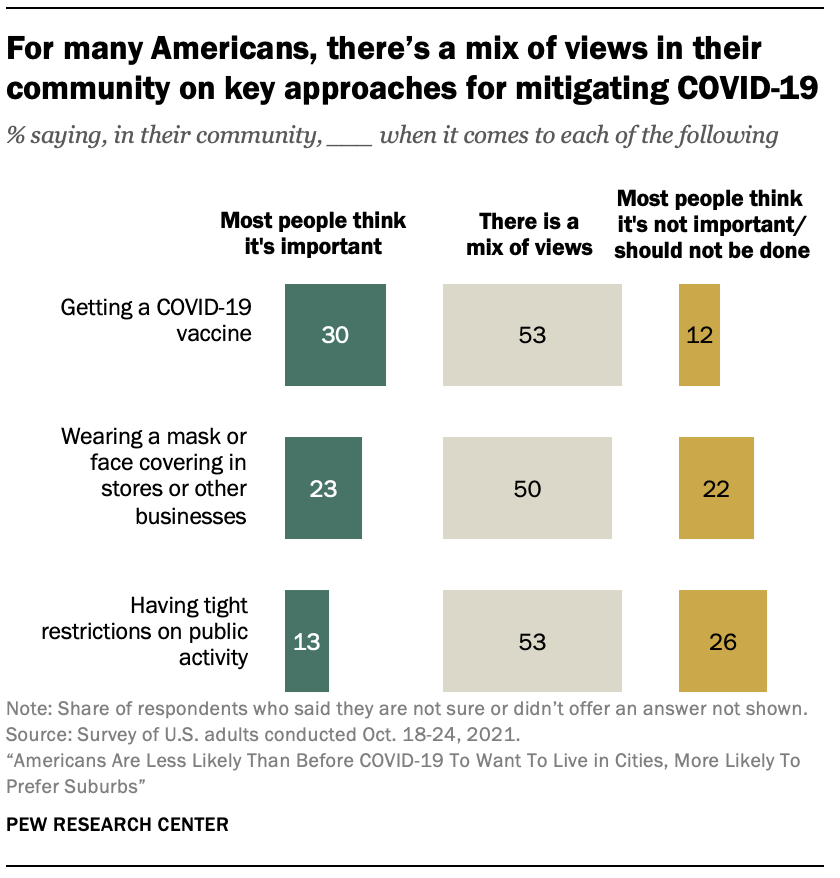

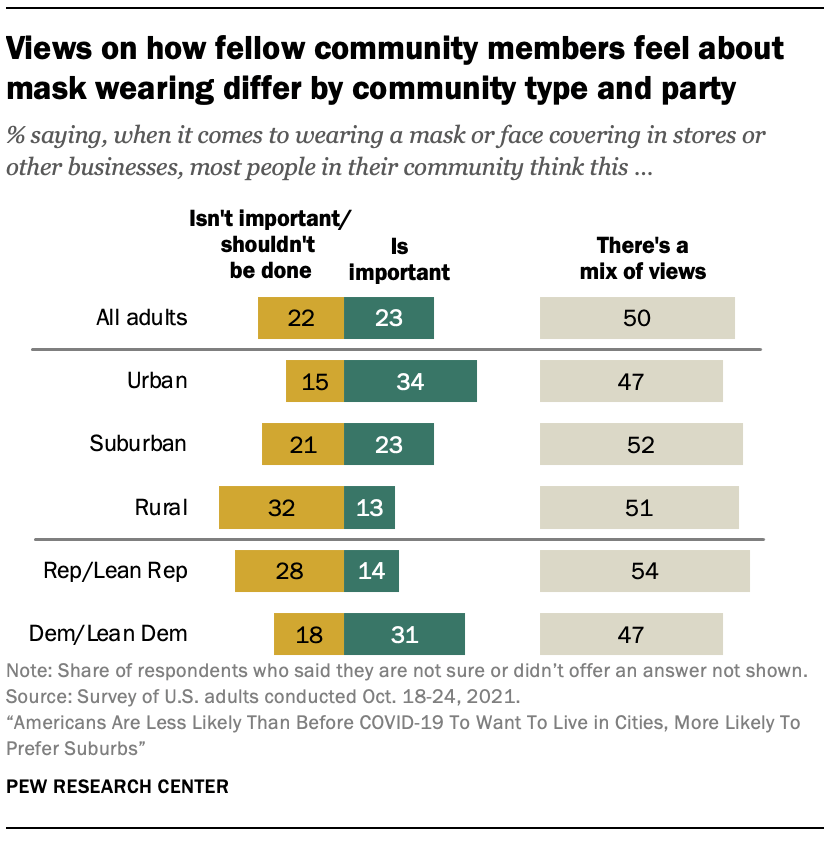

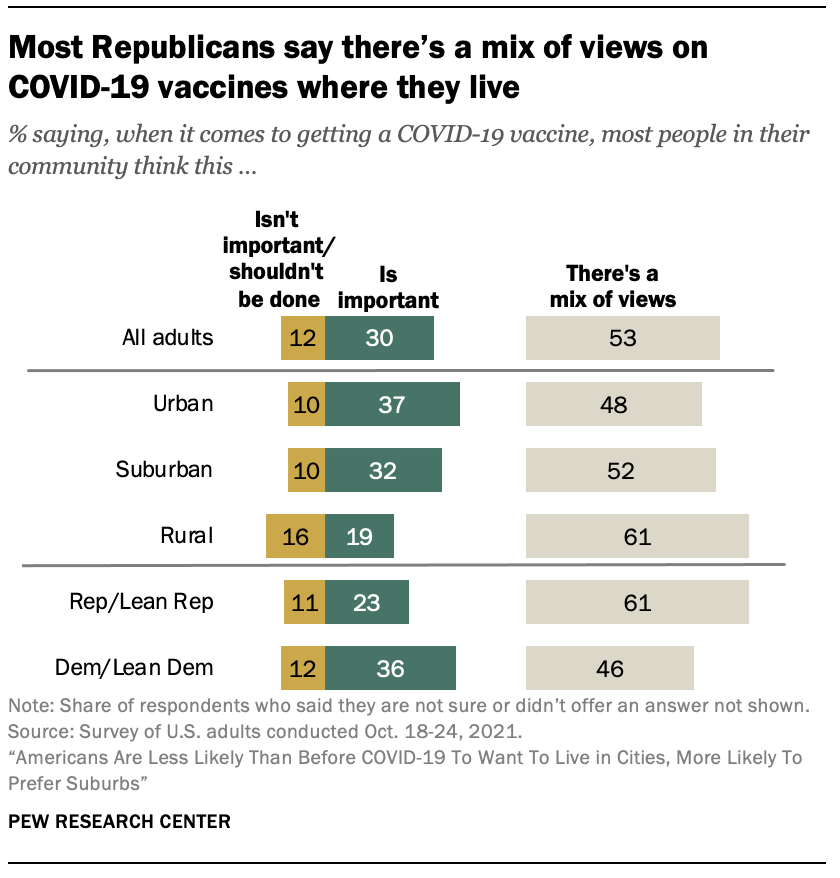

At least half of Americans say there is a mix of views on vaccines, masks and COVID-19 restrictions in their local community. To the extent that there is more uniformity in views, 30% say most people in their community think getting a COVID-19 vaccine is important, while 12% say most people think this is not important or shouldn’t be done. On mask wearing, 23% say most people in their community think wearing a mask in stores and other businesses is important, while about the same share (22%) say most don’t think it’s important or think it shouldn’t be done. When it comes to restrictions on public activities, 13% say most people where they live think it’s important to have tight restrictions, while twice as many say most people in their community don’t think this is important or think it shouldn’t be done. These views differ substantially across community types, with rural adults less likely than those who live in urban and suburban areas to say most people in their community think these things are important.

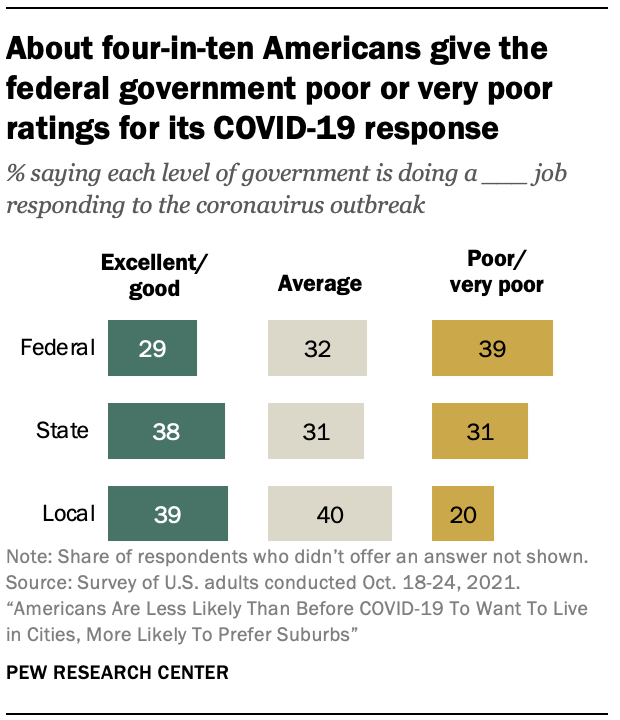

State and local governments receive higher ratings than the federal government for their handling of the coronavirus outbreak, but no level of government is seen as doing an excellent or good job by a majority of Americans. About four-in-ten give their state (38%) and local (39%) government a positive rating, while just 29% think the federal government is doing an excellent or good job responding to the pandemic (a 39% plurality say the federal government is doing a poor or very poor job, while 32% say it is average). Republicans are particularly negative in their views of how the federal government has handled the pandemic, with 65% saying it has done a poor or very poor job, compared with 18% of Democrats who say the same.

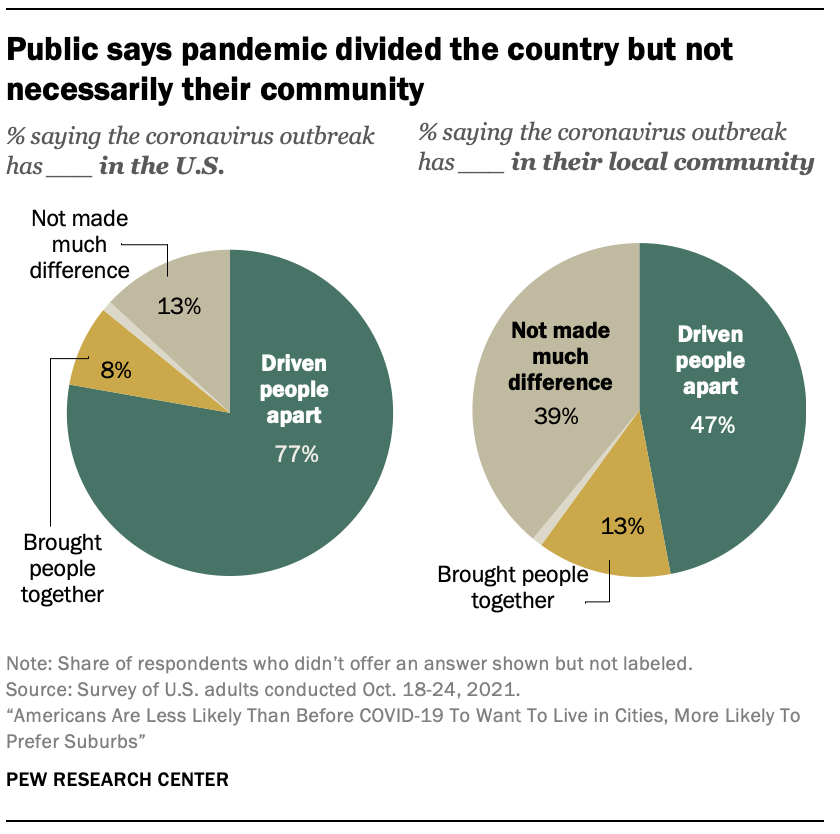

About three-quarters of Americans (77%) say the pandemic has divided people in the country as a whole. Just 8% say the pandemic has brought people in the U.S. together and 13% say it hasn’t made much difference. Republicans and Republican leaners are more likely than Democrats and those who lean Democratic to say the pandemic has driven people apart – both in the country and in their local communities. But at least three-quarters in both parties say this about people in the U.S., and more than four-in-ten say it about people in their community.

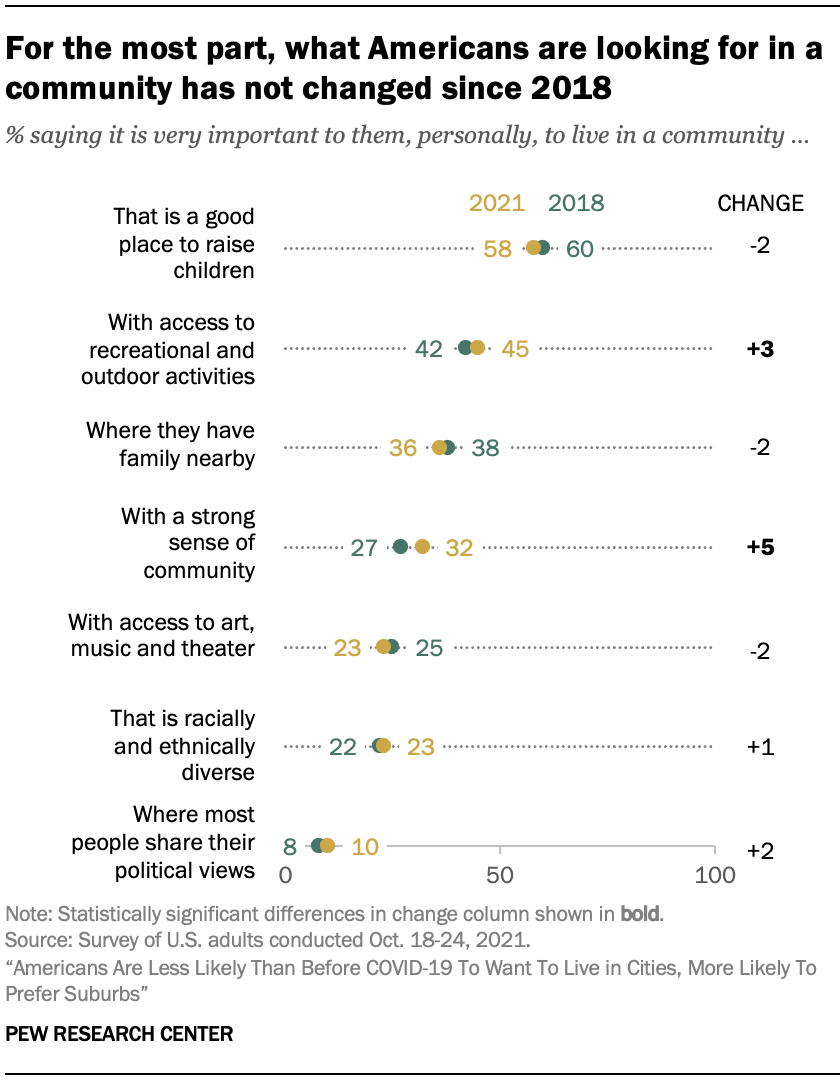

For the most part, what Americans are looking for in a community hasn’t changed considerably since 2018. The share of U.S. adults who say it’s very important to them, personally, to live in a place with a strong sense of community is up from 27% in 2018 to 32% today, and this is especially the case among those who live in urban and rural areas (up 8 and 10 percentage points, respectively). There has also been a modest 3-point increase in the share saying it’s very important to them to live in a community with access to recreational and outdoor activities. Living in an area that’s a good place to raise children remains the most valued feature of a community (58% say this is very important). On this and all other factors asked about in the survey – living near family; living in a community with access to art, music and theater; and living in a community that is racially and ethnically diverse or where most people share your political views – the shares who consider each a priority are virtually unchanged from 2018.

The share of Americans who are satisfied with the quality of life in their local community has dropped since 2018, but most are at least somewhat satisfied. About three-quarters of U.S. adults (74%) say they are at least somewhat satisfied with the quality of life in their local community, with 24% saying they are very satisfied. These shares are down from 79% and 27%, respectively, in 2018. The share expressing high levels of satisfaction with the quality of life in their community has dropped by 5 percentage points in urban and suburban areas (from 23% to 18% in cities and from 31% to 26% in suburbs). There has been no significant change in rural communities (26% said they were very satisfied in 2018 and 24% say this today).

Assessments of the ongoing effects of the pandemic differ by community type, race, ethnicity and income

The COVID-19 pandemic may not have drastically changed people’s preferences for where and how they want to live, but there’s no questioning that it had a profound impact on American life at both the community and individual level. About a third or more of adults say it will be more than two years before their communities and their own lives return to normal.

More than a year and half after the start of the pandemic, majorities of Americans say the economic and health impacts of the coronavirus outbreak are either a major or minor problem in their local community. Roughly a third (34%) say the economic impact is a major problem, and 26% say the same about the health impact.

Across community types, the impact is felt more acutely in urban areas. Some 45% of urban adults say the economic effect of COVID-19 is a major problem in their local community. This compares with 31% of suburban and 33% of rural residents. Similarly, while 37% of adults in urban areas say the health impact of the pandemic is a major problem where they live, smaller shares of suburban (23%) and rural (24%) adults say the same.

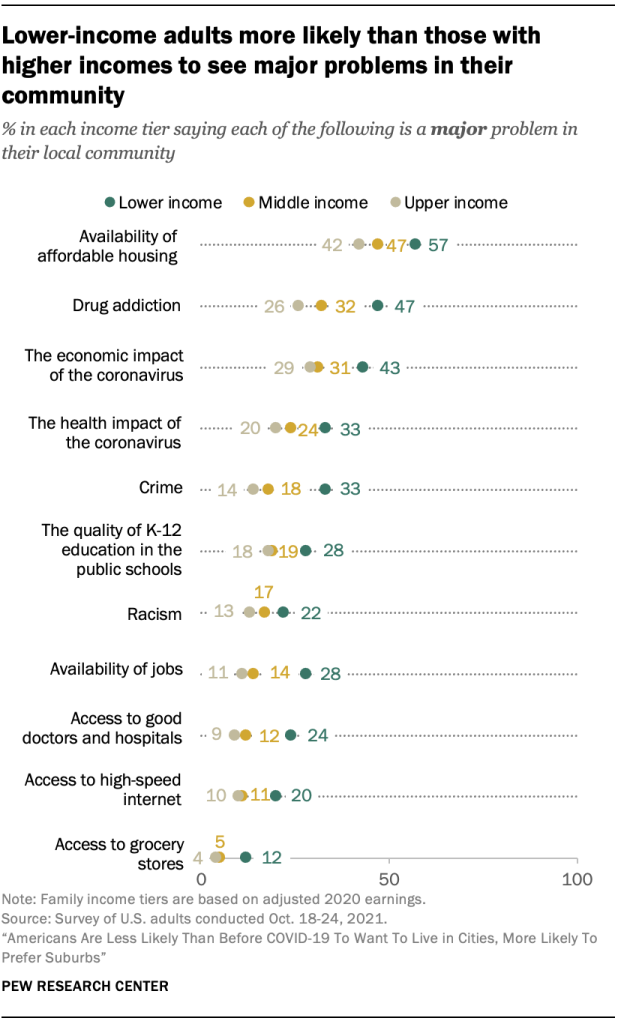

Perceptions about the impact of COVID-19 on communities also differ by income and race and ethnicity. Adults with lower incomes (43%) are significantly more likely than middle-income (31%) and upper-income (29%) adults to say the economic impact of the pandemic is a major problem in their community. And the pattern is similar when it comes to the health impact: A third of lower-income adults, compared with 24% of middle-income and 20% of upper-income adults, say this a major problem where they live.

These income differences are seen in suburban and rural areas. In these types of communities, lower-income adults are more likely than their middle- and upper-income counterparts to see the economic and health impacts of COVID-19 as a major problem.

Black and Hispanic adults are much more likely than White or Asian adults to say the economic impact of the pandemic is a major problem in their local community: 48% of Black adults and 46% of Hispanic adults say this, compared with 30% of White adults and 29% of Asian Americans. Black adults are the most likely among the major racial and ethnic groups to say the health impact of COVID-19 is a major problem where they live – 46% say this compared with 35% of Hispanic adults and smaller shares of White (21%) and Asian (22%) adults.

Across urban and suburban communities, higher shares of Black and Hispanic adults say the economic and health impacts of the pandemic are major problems where they live, compared with White adults. (There are too few Black, Hispanic or Asian adults in rural areas to analyze separately and too few Asian Americans in urban and suburban areas.)

Perceptions also differ by party. Democrats and those who lean Democratic (38%) are more likely than Republicans and Republican leaners (29%) to say the economic impact of the pandemic is a major problem in their community. And the gap is considerably wider in assessments of the health impact: 35% of Democrats but only 16% of Republicans say this is a major problem where they live. The partisan gap on the economic and health impact persists across urban, suburban and rural communities.

People who live in communities with a higher number of deaths related to COVID-19 in the past eight weeks are more likely than those living in communities with fewer deaths to say the health impact of the coronavirus outbreak is a major problem in their local area. About three-in-ten adults in higher impact communities (31%) say this, compared with 23% in medium-impact areas and 25% in lower-impact areas.5

Many Americans see a long road ahead until life gets back to the way it was before the pandemic

Americans have mixed views on how long it will take for life to get back to normal in their local community. Some 36% say it will be more than two years before things get back to the way they were before the pandemic, including 19% who say things will never get back to normal in their community. About three-in-ten adults (31%) say life will be back to normal in their community one to two years from now, and about a third say it will take less than a year (20%) or that life in their community never really changed or has already gotten back to where it was (13%).

When asked about their local economy, Americans have similar responses. About four-in-ten (39%) say it will be more than two years before the economy in their area returns to how it was before the coronavirus outbreak, including 14% who say it will never come back. Three-in-ten say it will take one to two years for the economy to recover, 18% say the economy will be back to where it was before COVID-19 in less than a year, and 10% say things never really changed or are already back to normal.

Adults who live in urban and rural communities have more pessimistic views than those living in the suburbs when it comes to both life in their community and their local economy returning to normal. For example, 41% of city dwellers and 37% of those in rural areas say it will take their community more than two years to recover – with about one-in-five saying it will never get back to the way it was. Among those living in the suburbs, 32% say it will take more than two years to return to normal (17% say it never will).

The differences by race and income level in perceptions of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic are echoed in views about the recovery. Black adults and those with lower incomes are particularly likely to say the return to normal for their community will be a long process. Among Black adults, 43% say it will take more than two years for life to return to normal in their community or it never will. Smaller shares of White (35%), Hispanic (36%) and Asian (28%) adults say the same. Even so, White (19%), Black (22%) and Hispanic (17%) adults are about equally likely to say things will never return to the way they were before the coronavirus outbreak, while Asian adults (5%) are much less likely to say this.

About four-in-ten lower-income adults (41%) say it will take more than two years for life in their local community to return to how it was before the pandemic. This includes 22% who say their community will never get back to how it was. By comparison, 34% of middle-income adults and 28% of those with upper incomes say it will take more than two years for their communities to return to normal.

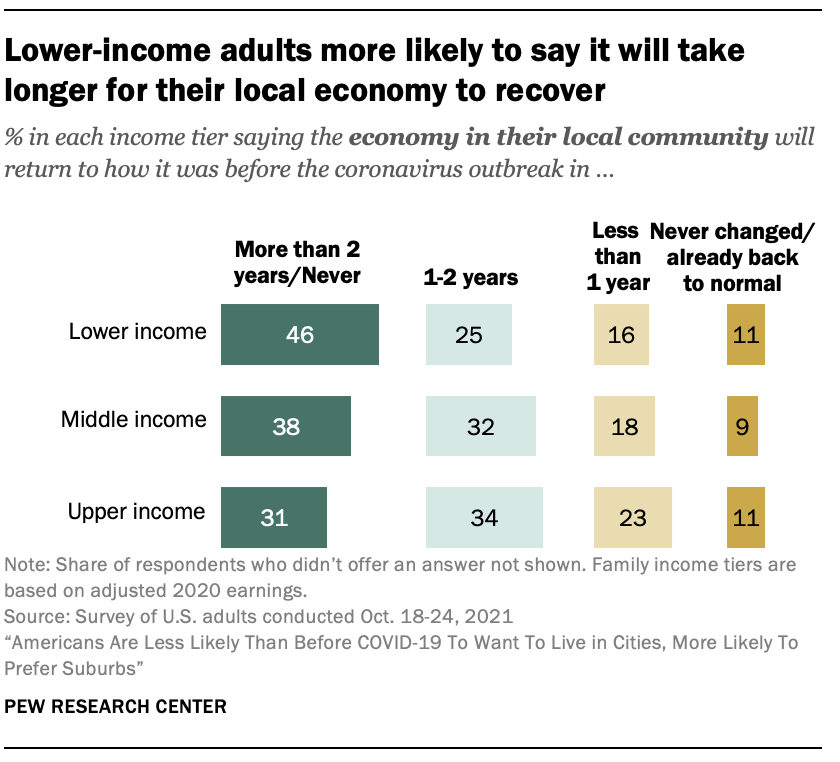

The patterns are similar for the economic recovery: 46% of lower-income adults say it will take two years or more for their local economy to come back from the pandemic, compared with 38% of middle-income and 31% of higher-income adults. Income gaps in assessments of the economic recovery are seen across community types, with lower- and middle-income adults more likely than those with upper incomes to see a longer road to recovery in cities and suburbs. In rural areas, those with lower incomes stand out as the most likely to see the recovery lasting two or more years.

There are partisan differences as well. Republicans (17%) are much more likely than Democrats (9%) to say life in their community never changed or has already returned to normal. Even so, Republicans (37%) are more likely than Democrats (34%) to say it will take more than two years for their communities to get back to the way they were before the pandemic. Similarly, Republicans are more likely than Democrats to say it will take more than two years for the local economy to return to normal.

Americans see a somewhat quicker return to normalcy when it comes to their own lives, with 42% saying either their life never really changed or has already returned to how it was before the pandemic (21%) or that it will be back to normal in less than a year (21%). About one-in-four adults (24%) say life will be back to normal for them in one to two years. Still, a substantial share (32%) say it will take more than two years for their lives to return to how they were before, including 20% who say things will never get back to normal.

Urban residents (36%) are somewhat more likely than those who live in suburban or rural areas (31% each) to say it will take two or more years for their lives to return to normal. There are income gaps as well, with higher shares of lower-income adults saying it will take more than two years to get back to normal, compared with middle- and upper-income adults.

While roughly equal shares of Republicans and Democrats say it will take more than two years for their lives to get to the way they were before the pandemic, Republicans (28%) are much more likely than Democrats (15%) to say their lives never changed or are already back to normal.

Most Americans say the pandemic drove people in the U.S. apart

Regardless of how they view the lingering impacts of the pandemic or the extent to which they believe their lives have returned to normal, there’s one thing most Americans agree on: The coronavirus outbreak has been a divisive event in the country. Fully 77% of all adults say the pandemic has driven people in the U.S. apart. Only 8% say it’s brought people together, and 13% say it hasn’t made much of a difference.

Large majorities across major demographic and political groups say the pandemic has driven Americans apart, including 73% or more in urban, suburban and rural communities. White adults (83%), four-year college graduates (83%) and upper-income adults (84%) are among the most likely to say the pandemic has driven people apart at the national level. Republicans (81%) are more likely than Democrats (75%) to express this view.

Americans are more ambivalent about whether the pandemic has united or divided people in their local communities. Overall, 47% say the coronavirus outbreak has driven people in their community apart, 13% say it has brought people together and 39% say it hasn’t made much of a difference.

Perceptions on this question are relatively consistent across community types. Similar shares of those living in urban (45%), suburban (48%) and rural (46%) areas say the pandemic has driven people in their local community apart. White adults (49%) are more likely than Black (41%) or Asian (33%) adults to say COVID-19 has been divisive within their community. Asian adults (52%) are more likely than other racial or ethnic groups to say it hasn’t made much of a difference. And, as with views on the country, Republicans (50%) are more likely than Democrats (45%) to say the pandemic has divided people in their local community.

There’s a diversity of views within many communities on vaccines, masks and COVID-19 restrictions

Some of the most divisive aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic have involved vaccines, mask wearing and restrictions on public activity. About half of Americans say they live in an area where there is a mix of views on these issues.

Some 53% of all adults say, in their local community, there is a mix of views when it comes to the importance of COVID-19 vaccines. Three-in-ten say most people in their community think getting a vaccine is important, and 12% say most think this is not important or should not be done (5% aren’t sure).

Similarly, half of all adults say there is a mix of views in their community on the importance of wearing masks or face coverings in stores or other businesses. Others see more consistency of views in their community: 23% say most people think wearing a mask is important, and a similar share (22%) say most think this is not important or should not be done.

When it comes to the importance of tight restrictions on public activity, 53% of all adults say there is a mix of views in their community on this issue. About one-in-four (26%) say most people in their area think having tight restrictions is not important or should not be done, and 13% say most people think having tight restrictions is important.

Perceptions on these issues differ by community type, some key demographic variables and political party identification. Rural residents are less likely than those living in urban or suburban areas to say most people in their community think each of the steps aimed at mitigating the virus is important – getting vaccines, wearing a mask and having tight restrictions on public activity. And, in turn, rural residents are more likely to say most people in their area think these things are not important or should not be done.

For example, on mask wearing, only 13% of rural residents (compared with 23% of those in the suburbs and 34% in cities) say most people in their communities think it’s important to wear a mask. About a third (32%) of people from rural areas (compared with 21% in the suburbs and 15% in urban areas) say most people in their community think wearing a mask is not important or shouldn’t be done. Roughly half in rural (51%) and suburban areas (52%) and 47% in cities say there’s a mix of views on this where they live.

There are also differences by race and ethnicity in people’s perceptions of how those in their community feel about these issues. On mask wearing, Asian (49%), Black (29%) and Hispanic (32%) adults are more likely than White adults (18%) to say most people in their community think wearing a mask is important. White adults are more likely than other groups to say most people where they live think it’s not important to wear a mask or that masks shouldn’t be worn. Still, 54% of White adults and pluralities of Black (47%) and Hispanic (44%) adults say there’s a mix of views in their community. The racial and ethnic patterns are similar on the issues of vaccines and restrictions on public activity.

Views also differ by income and education, particularly when it comes to vaccines. College graduates and upper-income adults are much more likely than those with less education or income to say most people in their community think getting a COVID-19 vaccine is important. Four-in-ten adults with a bachelor’s degree or more education say this, compared with 25% of those with less education. Similarly, 40% of upper-income adults – compared with 27% of middle-income and 28% of lower-income adults – say most people in the area where they live think it’s important to get a vaccine.

Partisan gaps on these issues are substantial. Democrats are more likely than Republicans to say they live in an area where most people think vaccines, masks and tighter restrictions are important, while Republicans are more likely to say most people where they live think masks and tighter restrictions are not important or should not be imposed. For example, 31% of Democrats but only 14% of Republicans say most people in their area think wearing masks is important. And 28% of Republicans but only 18% of Democrats say most in their community think this is not important or should not be done.

On vaccines, a higher share of Republicans than Democrats say there is a mix of views in their community. Even so, a plurality of Democrats say they live in an area where views on this issue are mixed.

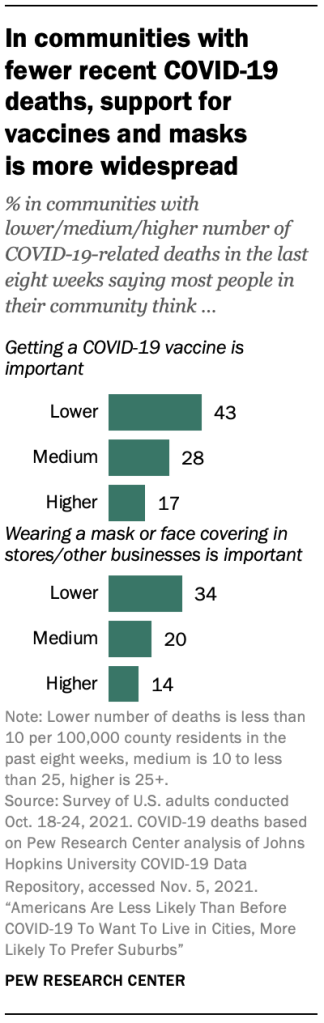

Adults who live in communities with a higher number of recent COVID-19-related deaths say there’s less support where they live for vaccines, masks and tight restrictions

Americans who live in communities that have been hit hard with COVID-19 deaths in recent weeks report less support among their fellow community members for vaccines, mask wearing and tight restrictions on public activity. Only 17% of those living in areas with a higher number of COVID-19-related deaths in the eight weeks prior to the survey say most people in their local community think getting a COVID-19 vaccine is important.6 By contrast, 28% of those living in areas with a medium number of recent COVID-19 deaths and 43% of those with a lower number of deaths say the same.

Similarly, while only 14% of those in areas with a higher number of recent deaths say most people in their community think wearing a mask or face covering in stores or other businesses is important, higher shares in communities with a medium (20%) or a lower (34%) number of deaths say the same.

The pattern is similar when it comes to views on having tight restrictions on public activity – those in areas with the highest number of COVID-19-related deaths in the past eight weeks are the least likely to say most people in their community think this is important.

These patterns are not driven by the partisan makeup of communities, as they can be seen among Republicans and Democrats.

Higher ratings for state and local government than federal government on COVID-19 response

Public assessments of the job government has done responding to the coronavirus outbreak are mixed and vary depending on the level of government. On balance, views of the federal government’s response to the pandemic are negative. About one-in-three adults say the federal government has done an excellent (5%) or good (24%) job, while 39% say it has done a poor (20%) or very poor (19%) job. Roughly a third (32%) say the federal government has done an average job responding to the coronavirus outbreak.

Views are somewhat more positive when it comes to the job state governments have done in responding to the pandemic: 38% say their state government has done an excellent (9%) or good (28%) job, and 31% say their state has done a poor (17%) or very poor (14%) job; 31% say their state has done an average job.

A similar share of adults have positive views of their local government’s handling of the pandemic: 7% say it has been excellent and 32% say it has been good. Views of local government are less negative than those of state and federal government, with 12% saying their local government has done a poor job and 8% saying very poor. Four-in-ten adults say their local government has done an average job.

Rural adults are less likely to give positive ratings to each level of government. The differences are sharpest on assessments of the federal government. For example, only 21% of rural residents give the federal government an excellent or good rating for its handling of the pandemic, compared with 30% of those in the suburbs and 36% of those in urban areas.

These views are driven in part by partisanship, as rural adults are disproportionately Republican, and Republicans are especially critical of the federal government’s handling of the coronavirus outbreak. Roughly two-thirds (65%) of Republicans say the federal government has done a poor or very poor job; only 18% of Democrats say the same. The party gap is significant, though not as wide, when it comes to the performance of state and local governments.

There are demographic differences in these ratings as well. Black, Hispanic and Asian adults give higher ratings to the federal government than do White adults. And college graduates give higher ratings to each level of government compared with non-college graduates.

Rising share of Americans say availability of affordable housing is a major problem in their area

Beyond the economic and health impacts of the coronavirus, many Americans see a variety of other problems in their area. About half (49%) say the availability of affordable housing is a major problem in their local community, while a smaller but substantial share say the same about drug addiction (35%). About one-in-five see crime (22%), the quality of K-12 education in local public schools (22%), racism (18%), and the availability of jobs (18%) as major problems, while smaller shares say access to good doctors and hospitals (15%), high-speed internet (13%) and grocery stores (7%) are major problems.

The share who consider the availability of affordable housing a major problem has increased 10 percentage points since the question was last asked in 2018. In turn, the shares saying drug addiction and the availability of jobs are major problems fell significantly. The availability of jobs saw the largest drop in the share saying it is a major problem – down 13 points from 31% in 2018. This change is particularly notable in rural areas, where the share saying the availability of jobs is a major problem dropped 19 percentage points, compared with a 12-point drop in urban areas and a 9-point drop in the suburbs.

On some issues, while the share of Americans saying each is a major problem in their area has only seen modest or no change, there has been greater movement in particular community types. For example, while the overall shares of U.S. adults who see crime and racism as major problems have not increased by more than 2 percentage points since 2018, this increase is much larger across urban areas. Some 43% of urban residents now say crime is a major problem in their community, compared with 35% in 2018. And 27% in urban areas now say this about racism, up from 21% in 2018.

Urban residents voice more concern across a broad range of issues. Fully 63% of urban residents say the availability of affordable housing is a major problem; 46% of suburban and 40% of rural residents say the same. About half of urban residents (49%) say drug addiction is a major problem in their area, compared with 40% of rural residents and an even smaller share in the suburbs (27%). In turn, rural residents are more likely to say access to good doctors and hospitals (22%) and high-speed internet (26%) are major problems; about one-in-five or fewer urban and suburban residents say the same. These patterns were similar in 2018.

Perceptions of these problems differ by race and ethnicity. For example, 42% of Black adults say crime is a major problem in their community, compared with 30% of Hispanic adults, 24% of Asian adults and 17% of White adults. And while about four-in-ten Black (42%) and Hispanic (41%) adults see drug addiction as a major problem in their area, 34% of White adults and an even smaller share of Asian adults (20%) say the same. In urban areas, where the issues included in the survey tend to be seen as more of a problem than in other community types, Black adults are more likely than their White and Hispanic counterparts to see drug addiction, crime and racism as major problems in their communities.7

Views on these issues also differ by income. Lower-income adults are significantly more likely than those with middle and upper incomes to see each of these issues as a major problem in their area. For example, a majority of lower-income adults say the availability of affordable housing is a major problem in their local community. Lower-income adults are also particularly likely to say drug addiction, crime and the availability of jobs are major problems.

These income differences are evident across community types, but lower-income adults in urban areas are even more likely to see drug addiction (59%) and crime (51%) as major problems. This is significantly more than the shares of lower-income adults in suburban and rural areas. In turn, lower-income adults in rural areas are more likely than those in urban and suburban areas to say access to high-speed internet (33%) is a major problem.

Americans less likely now to want to live in cities, more likely to prefer suburbs compared with 2018

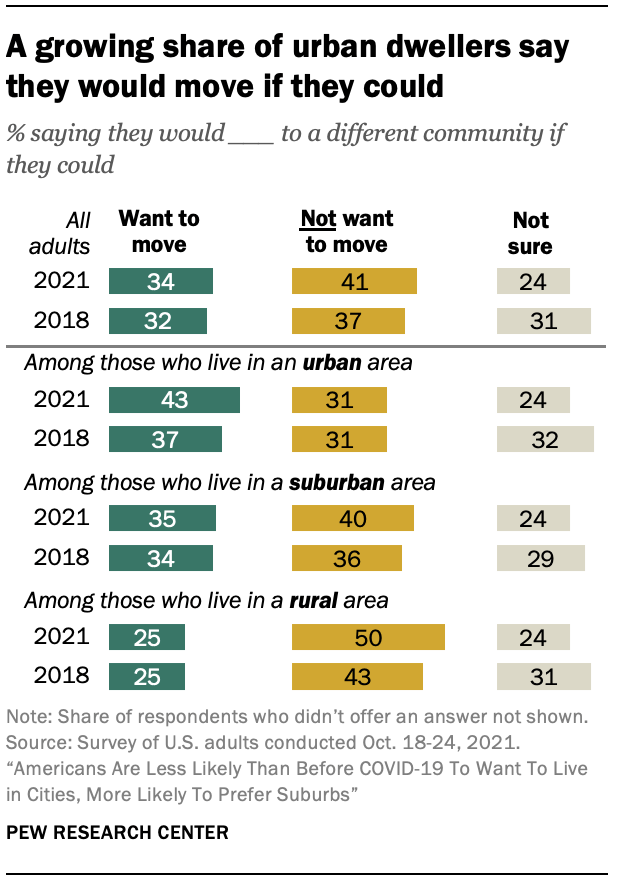

About a third of U.S. adults (34%) say they would want to move to a different community if they could, and those in urban areas are particularly likely to say this. Some 43% of urban dwellers say they would like to move, compared with 35% in suburbs and an even smaller share of those in rural areas (25%). Urban residents are also more likely than they were in 2018 to say they would want to move to a different community if they could: 37% said this in the earlier survey.

In contrast, the share of adults in suburban and rural communities who say they would want to move is virtually unchanged. Adults in these types of communities are now more likely than in 2018 to say they would not want to move (40% now vs. 36% in 2018 in the suburbs and 50% vs. 43% in rural areas). These changes reflect a drop in the shares in each of these community types who say they aren’t sure if they’d want to move if they could.

About three-in-ten adults in urban areas who say they would want to move (28%) say they would want to stay in an urban area, while 48% would want to move to the suburbs and 23% say they would want to move to a rural area. These responses have not changed significantly from 2018.

Among suburban residents who say they would want to move if they could, 37% would want to stay in the suburbs, while 43% would want to move to a rural area and just 19% would want to move to an urban community. The share saying they would want to move to a rural area (among those who would want to move) is up from 35% in 2018, while there was no significant change in the shares saying they’d want to stay in the suburbs or move to an urban area.

Rural dwellers who say they would want to move are the most likely to say they’d want to stay in the same community type: 46% would want to stay in a rural area. A third of rural residents who would move if they could say they would want to move to a suburb, while 19% would move to an urban area. Similar shares expressed these preferences in 2018.

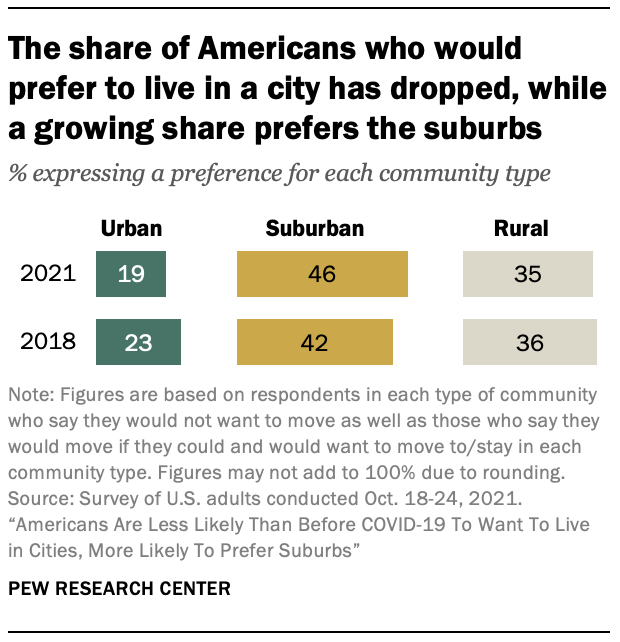

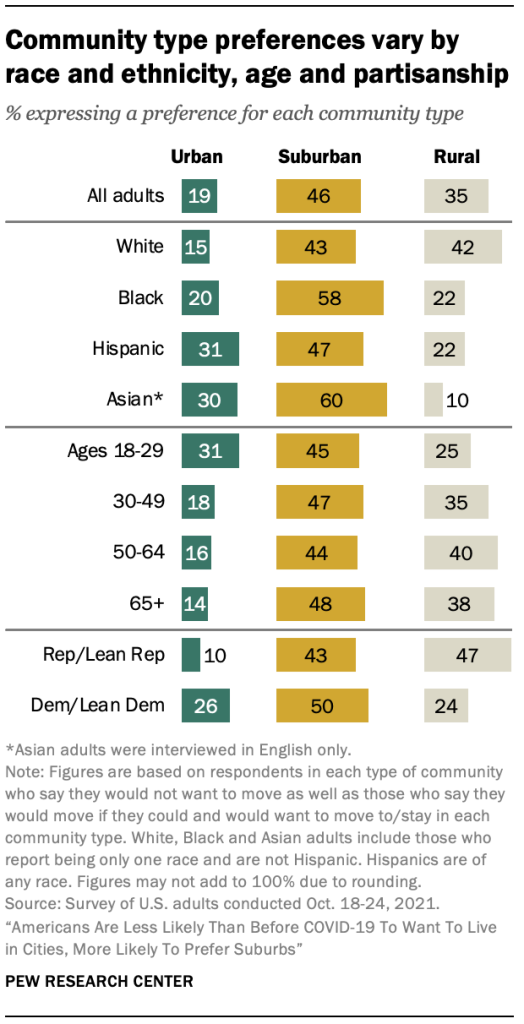

Overall, the share of U.S. adults who express a preference for living in an urban area has dropped from 23% in 2018 to 19% in 2021. This includes urban dwellers who do not want to move or who want to move but still live in an urban area, as well as those from the suburbs and rural areas who say they’d like to move to a city.8

At the same time, the share who would prefer living in the suburbs (either staying put or moving to the suburbs) is up 4 percentage points, from 42% to 46%. Some 35% prefer living in a rural area, virtually unchanged from the 36% who did so three years ago.

Across most age groups, more prefer suburbs to cities or rural areas; the exception are adults ages 50 to 64, similar shares of whom prefer suburban (44%) and rural (40%) communities. Still, adults younger than 30 who express a preference are more likely than those in older age groups to prefer living in an urban area: 31% of adults ages 18 to 29 would prefer to live in a city, compared with 18% of those ages 30 to 49, 16% of those ages 50 to 64 and 14% of adults ages 65 and older. Substantial shares in each age group would like to live in a suburban community, including 45% of those younger than 30 and 48% of those 65 and older.

About six-in-ten Black (58%) and Asian (60%) adults who express a preference would want to live in a suburban area, compared with 47% of Hispanic adults and 43% of White adults. Hispanic adults (31%) are more likely than Black (20%) and White (15%) adults to express a preference for urban areas, and Asian adults (30%) are more likely than those who are White to do so.9 In turn, White adults are the most likely to express a preference for rural areas: 42% do so, compared with 22% each of Black and Hispanic adults and just 10% of Asian adults.

There are also differences by partisanship. Among Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents who express a preference, half would prefer to live in the suburbs, while the rest are split between those who would prefer living in cities (26%) and those who would prefer a rural area (24%). Among Republicans and Republican leaners, similar shares express a preference for rural (47%) and suburban areas (43%), while just 10% would prefer to live in an urban community.

People’s priorities for what they are looking for in a community are largely unchanged compared with before the pandemic

While the survey shows some changes in the shares of Americans who would prefer to live in cities and suburbs compared with 2018, there is little evidence that people’s priorities in terms of what they consider important in a community have shifted considerably during this time. In particular, the shares saying it is very important to them to live in a community that is a good place to raise children; where they have family nearby; with access to art, music and theater; that is racially and ethnically diverse; or where most people share their political views have changed by no more than 2 percentage points between 2018 and 2021.

The share of Americans who see living in a community with access to recreational and outdoor activities as a high priority has seen a modest but statistically significant increase: 45% now say this is very important to them, compared with 42% in 2018. And there has also been a rise in the share saying it is very important to them to live in a place with a strong sense of community (32% say this today vs. 27% in 2018).

Adults in urban and rural communities are more likely than they were in 2018 to see living in a place with a strong sense of community as a high priority. Some 37% of city dwellers and 35% of those in rural areas now say this is very important to them, compared with 29% and 25%, respectively, in 2018. However, there has been no significant change among those in the suburbs: 29% say it’s very important to them to live in a place with a strong sense of community, similar to the 27% who said this in the earlier survey.

Overall, about six-in-ten U.S. adults (58%) say it’s very important to them, personally, to live in a community that is a good place to raise children. Smaller shares say the same about living in a place with access to recreational and outdoor activities (45%), where they have family nearby (36%), with a strong sense of community (32%), with access to art, music and theater (23%), that is racially and ethnically diverse (23%), or where most people share their political views (10%).

These preferences vary to some extent by age, race and ethnicity, and partisanship. For example, Black adults (49%) are more likely than Hispanic (33%), White (30%) or Asian (29%) adults to say it’s very important to them, personally, to live in a place with a strong sense of community. And Black (44%), Asian (35%) and Hispanic (32%) adults are more likely than White adults (16%) to see living in a community that is racially and ethnically diverse as a priority.

Adults younger than 30 are also more likely than older adults to say it’s very important to them to live in a racially and ethnically diverse community: 33% of those ages 18 to 29 say this, compared with 25% of adults ages 30 to 49, 21% of those ages 50 to 64 and just 16% of adults ages 65 and older. In turn, adults ages 65 and older are the most likely to say living in a community where they have family nearby is very important to them (44% say this vs. 38% of those ages 50 to 64, 31% of those 30 to 49 and 33% of adults younger than 30).

When it comes to partisan differences, Democrats and those who lean toward the Democratic Party are more likely than Republicans and Republican leaners to say it would be very important to them, personally, to live in a community with each of these characteristics: access to recreational and outdoor activities (50% of Democrats vs. 39% of Republicans), racial and ethnic diversity (36% vs. 9%) and access to art, music and theater (32% vs. 12%). There are no significant differences in the shares of Republicans and Democrats who see the other items asked in the survey as very important.

Share of U.S. adults who live near family is largely unchanged from 2018

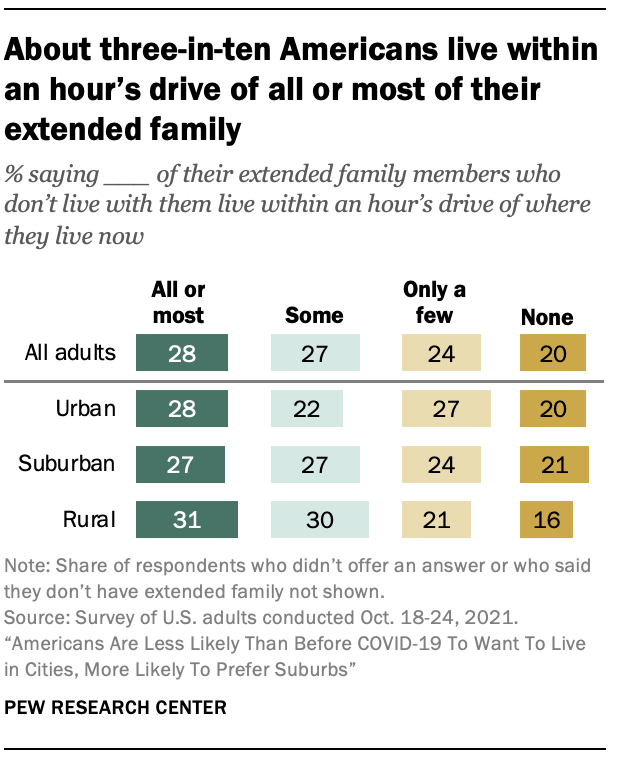

A quarter of U.S. adults say they have moved since the coronavirus outbreak, including 6% who say they moved for reasons related to the pandemic, but the share of adults who live near family members is unchanged. Some 55% say at least some members of their extended family live within an hour’s drive from them, including 28% who say all or most of their family members do (in 2018, these figures were 55% and 29%, respectively).

Adults in rural areas (62%) are more likely than those in cities (50%) or suburbs (54%) to say at least some of their family members live within an hour’s drive from them. In turn, about one-in-five adults in urban (20%) and suburban (21%) communities say none of their family members live nearby, compared with 16% in rural areas.