The Canadian province of Quebec recently enacted a new law that bans many public employees – including teachers, police officers and judges – from wearing religious symbols in the workplace. While advocates of the measure say it promotes the separation of church and state, opponents already have challenged the law in court, saying it targets Muslim women and erodes religious freedom.

Quebec is not the only jurisdiction to enact restrictions on religious dress in public. In fact, France, which once ruled Quebec as part of a large North American colony known as “New France,” banned head scarves and other religious symbols in public schools in 2004, and banned full-face veils in all public places in 2011. A ban on face veils is also in force in several other European countries. Although Pew Research Center has not asked Canadians for their opinions on these laws, most people across Western Europe favor at least some restrictions on Muslim women’s dress.

Here are five facts about religion in Canada, based on Pew Research Center data:

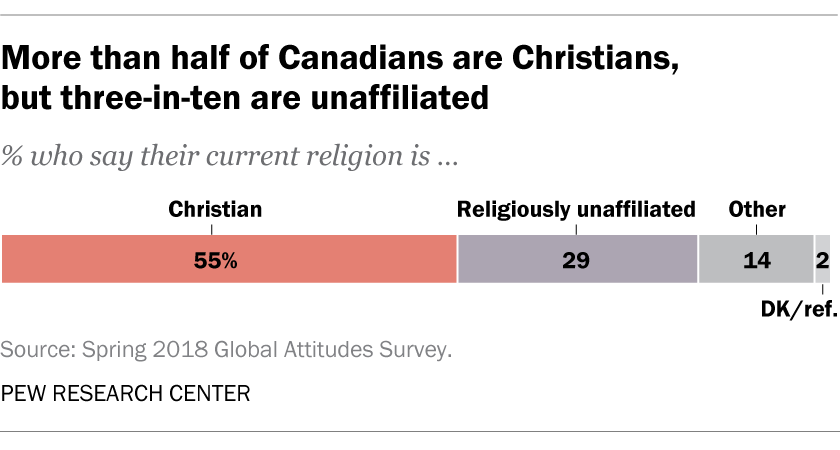

A declining share of Canadians identify as Christians, while an increasing share say they have no religion – similar to trends in the United States and Western Europe. Our most recent survey in Canada, conducted in 2018, found that a slim majority of Canadian adults (55%) say they are Christian, including 29% who are Catholic and 18% who are Protestant. About three-in-ten Canadians say they are either atheist (8%), agnostic (5%) or “nothing in particular” (16%). Canadian census data indicate that the share of Canadians in this “religiously unaffiliated” category rose from 4% in 1971 to 24% in 2011, although it is lowest in Quebec. In addition, a rising share of Canadians identify with other faiths, including Islam, Hinduism, Sikhism, Judaism and Buddhism, due in large part to immigration. The 2018 Pew Research Center survey found that these five groups together make up 8% of Canadian adults.

Most Canadians say religion’s influence in public life is waning in their country. Our 2018 survey found that roughly two-thirds of Canadian adults (64%) say religion has a less important role in their country than it did 20 years ago. Indeed, just 12% say religion has become more important in Canadian society. There is no consensus on whether this is good or bad: 37% of Canadians favor a more important role for religion, while 29% disagree and oppose any more influence for religion in public life. One-in-five have no preference either way.

Canada has low levels of government restrictions on religion, according to a Pew Research Center study using data from 2016, the most recent year available. The country’s constitution protects the freedom of religion, and its Supreme Court ruled in 2006 that a Quebec school could not prohibit a Sikh child from carrying a symbolic kirpan (dagger) at school. Sikh men in the Royal Canadian Mounted Police also are exempt from wearing hats so they can wear turbans, as required by their faith. More recently, in 2018, a Quebec court ruled that a Muslim woman was wrongly told to remove her hijab in a courtroom, and that head scarves should be allowed in court if they do not harm the public interest.

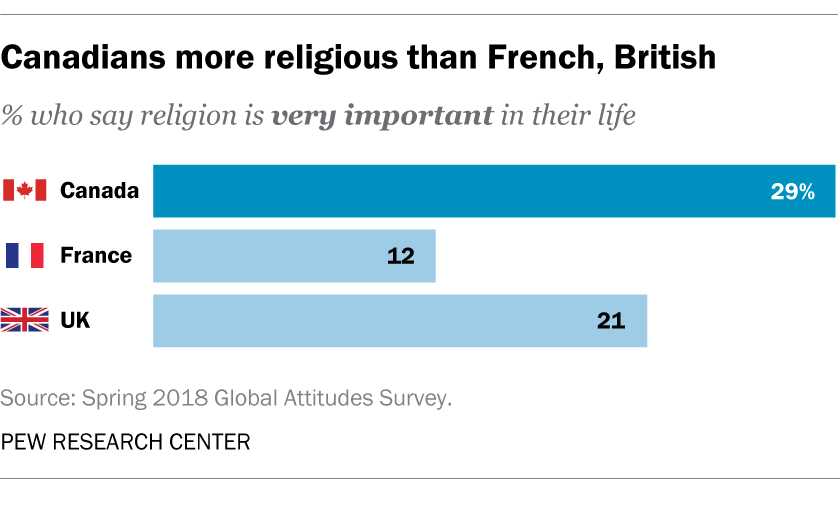

Relatively few Canadians engage frequently in traditional religious practices, such as daily prayer or weekly worship. We most recently asked Canadians about these behaviors in 2013, when one-in-five reported attending religious services at least weekly, and 29% said they pray daily. Around a third (36%) said they never pray, and about half said they seldom (24%) or never (25%) go to church or other worship services. Still, more than half of all Canadians (55%) in the Center’s 2018 survey said religion remains at least somewhat important in their lives, including about three-in-ten (29%) who said it is very important to them – higher than the share who said this in the UK, France and most other Western European countries. By all of these measures, young Canadian adults are less religious than their elders.

Two-thirds of Canadians (67%) say it is not necessary to believe in God in order to be moral and have good values. This figure has been largely steady across three surveys conducted by Pew Research Center in 2002, 2007 and 2013. About three-in-ten Canadians take the opposite view, saying that in order to have good values, belief in God is essential.