Lebanese protests that were in part prompted by a proposed tax on the use of the messaging platform WhatsApp have since turned into a broader call for rebuilding the nation’s political and economic system. In response to the demonstrations, Lebanon’s prime minister, Saad Hariri, announced he was resigning at the end of October to make way for a new government.

Amid the unrest, here is a closer look at the widespread use of WhatsApp in Lebanon, as well as public unhappiness with the country’s political and economic situation. All findings are based on Pew Research Center surveys conducted in 2018 and 2019.

Who uses WhatsApp in Lebanon?

The protests initially broke out in part as a response to the Lebanese government proposing a tax on WhatsApp, a popular messaging platform that can be used to send encrypted text and audio messages, make audio and video calls and share digital content.

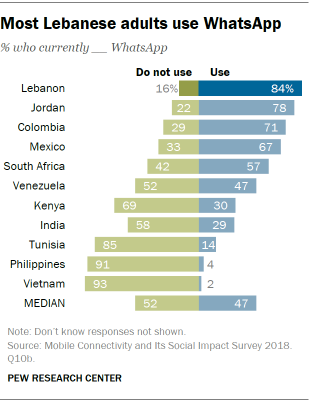

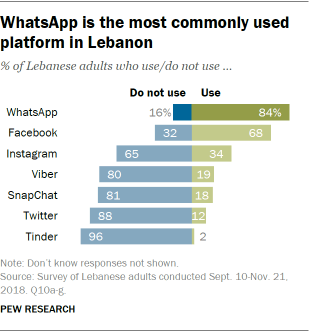

In a survey conducted in fall 2018, more than four-in-five Lebanese adults (84%) said they use WhatsApp, the highest rate among 11 emerging economies included in the survey. It is the most commonly used social network or messaging platform in Lebanon, beating out Facebook, Instagram and other platforms.

WhatsApp is especially popular among young people in Lebanon. Nearly all Lebanese adults ages 18 to 29 (98%) say they use the platform, as do 94% of those ages 30 to 49, compared with 60% of those 50 and older.

Wide majorities are unhappy with Lebanon’s political system

Many of the recent protests in Lebanon have featured chants calling on all politicians to step down and for the current sectarian governing arrangement to be replaced with a new system.

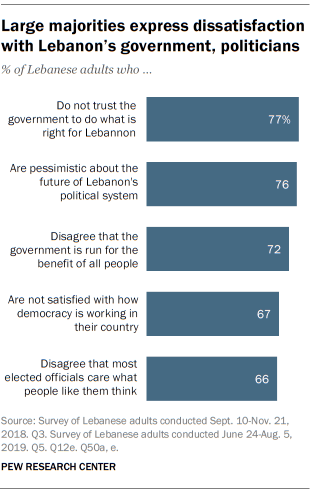

When polled in fall 2018, roughly four-in-five Lebanese adults (77%) said they do not trust their government to do what is right for Lebanon, at least to some extent. That included about half of Lebanese (53%) who said they do not trust their government to do what is right for their country at all.

A subsequent survey in summer 2019 found widespread discontent on a number of other questions. Around two-thirds or more of Lebanese adults said they are pessimistic about the future of their country’s political system (76%); disagree that the government is run for the benefit of all people (72%); are dissatisfied with how their country’s democracy is working (67%); and do not think most elected officials in their country care what people like them think (66%).

There has been an especially dramatic reversal in opinion when it comes to whether the Lebanese government is run for the benefit of all people. When the Center last asked this question in Lebanon in 2002, only 21% disagreed that the government worked for the benefit of its constituents, while 78% agreed.

Most are not confident in Lebanon’s economic prospects

Lebanon’s economy has also been a flashpoint for demonstrators, particularly those protesting in poorer areas, like Tripoli.

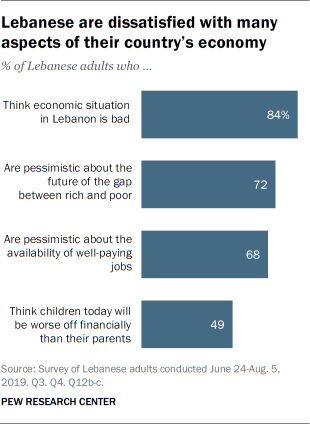

In the Center’s 2019 poll, 84% of Lebanese said their country’s economic situation is bad, with half saying the economic situation is very bad. And about half (49%) said that children today will be worse off financially than their parents.

In addition to widespread doubt surrounding economic conditions in general, 72% of Lebanese said they are pessimistic that the gap between the rich and poor will improve in the future. A similar share expressed concern about the future of the labor market: 68% said they doubt that well-paying jobs will be available in the future.

How different religious and age groups in Lebanon view the political and economic situation

In a country traditionally marked by sectarian divides, recent demonstrations have been notably intersectional, bridging religious, generational and socio-economic divisions.

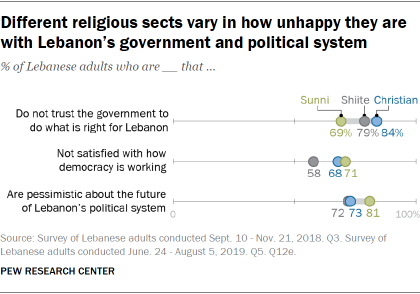

Still, some religious groups in Lebanon have more negative attitudes toward certain issues than others. For example, Christians are somewhat more likely than Muslims, both Sunni and Shiite, not to trust that the government will do what is right for their country.

However, Shiites are generally less likely than Sunnis and Christians to be dissatisfied with how democracy is working. And Christians and Shiites are somewhat less likely to be pessimistic about the future of Lebanon’s political system than Sunnis.

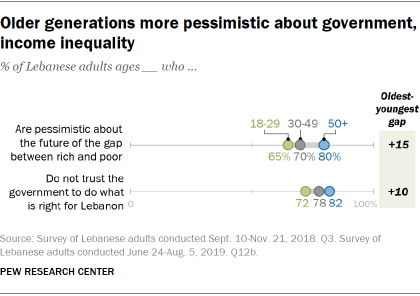

In general, older generations tend to express more pessimism than younger generations. Older Lebanese are more likely than younger adults not to trust the government to act in the best interest of the country and to be pessimistic about the future economic gap between the rich and poor.

People with incomes below the national median also tend to express more dissatisfaction with how democracy is working in Lebanon. About seven-in-ten lower-income Lebanese (71%) say they are not satisfied with how democracy is working in their country, compared with about six-in-ten (62%) of those with higher incomes.

While significant differences between religious, age, and socio-economic groups exist on many of the key issues defining the recent protests, large shares among all groups have expressed frustration and dissatisfaction with the political and economic conditions in Lebanon.

Note: See full topline results and methodology.