How we did this

Pew Research Center conducted this study to understand how Americans are continuing to respond to the coronavirus outbreak, their assessments of scientists and the role of scientific experts in policy. For most of the questions in this analysis, we surveyed 10,957 U.S. adults from April 29 to May 5, 2020. Questions about public confidence in scientists and medical scientists to act in the best interests of the public and questions about the ethical standards of medical doctors were asked in a survey of 10,139 U.S. adults from April 20 to 26, 2020.

Everyone who took part in either survey is a member of Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology.

See here to read more about the questions used for this report, along with responses, and its methodology.

Americans’ confidence in medical scientists has grown since the coronavirus outbreak first began to upend life in the United States, as have perceptions that medical doctors hold very high ethical standards. And in their own estimation, most U.S. adults think the outbreak raises the importance of scientific developments.

Scientists have played a prominent role in advising government leaders and informing the public about the course of the pandemic, with doctors such as Anthony Fauci and Deborah Birx, among others, appearing at press conferences alongside President Donald Trump and other government officials.

But there are growing partisan divisions over the risk the novel coronavirus poses to public health, as well as public confidence in the scientific and medical community and the role such experts are playing in public policy.

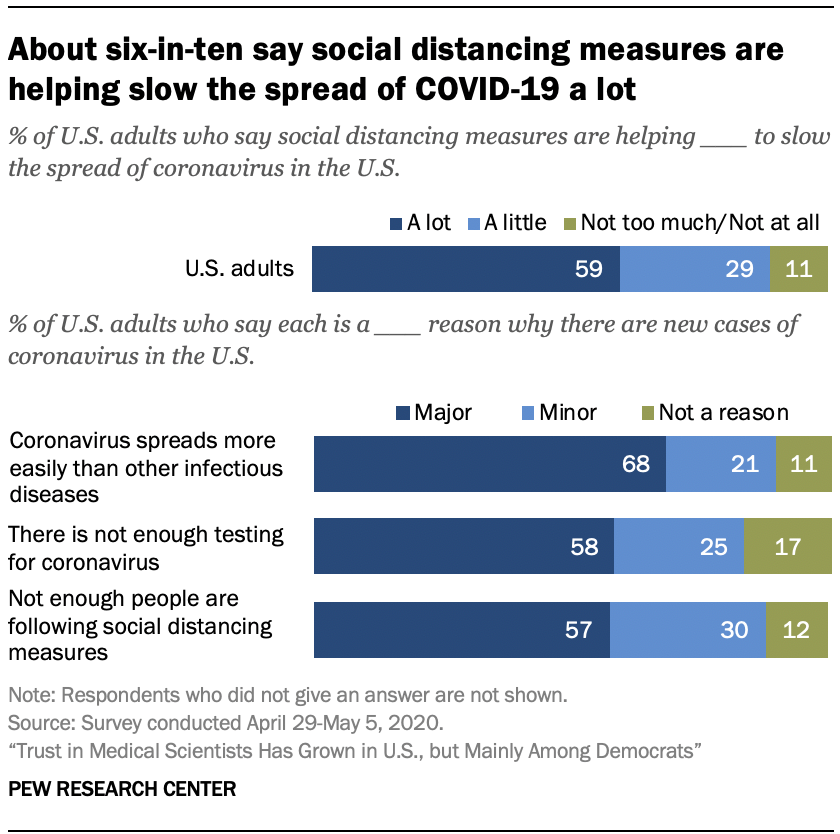

Still, most Americans believe social distancing measures are helping at least some to slow the spread of the coronavirus disease, known as COVID-19. People see a mix of reasons behind new cases of infection, including limited testing, people not following social distancing measures and the nature of the disease itself.

These are among the key findings from a new national survey by Pew Research Center, conducted April 29 to May 5 among 10,957 U.S. adults, and a new analysis of a national survey conducted April 20 to 26 among 10,139 U.S. adults, both using the Center’s American Trends Panel.

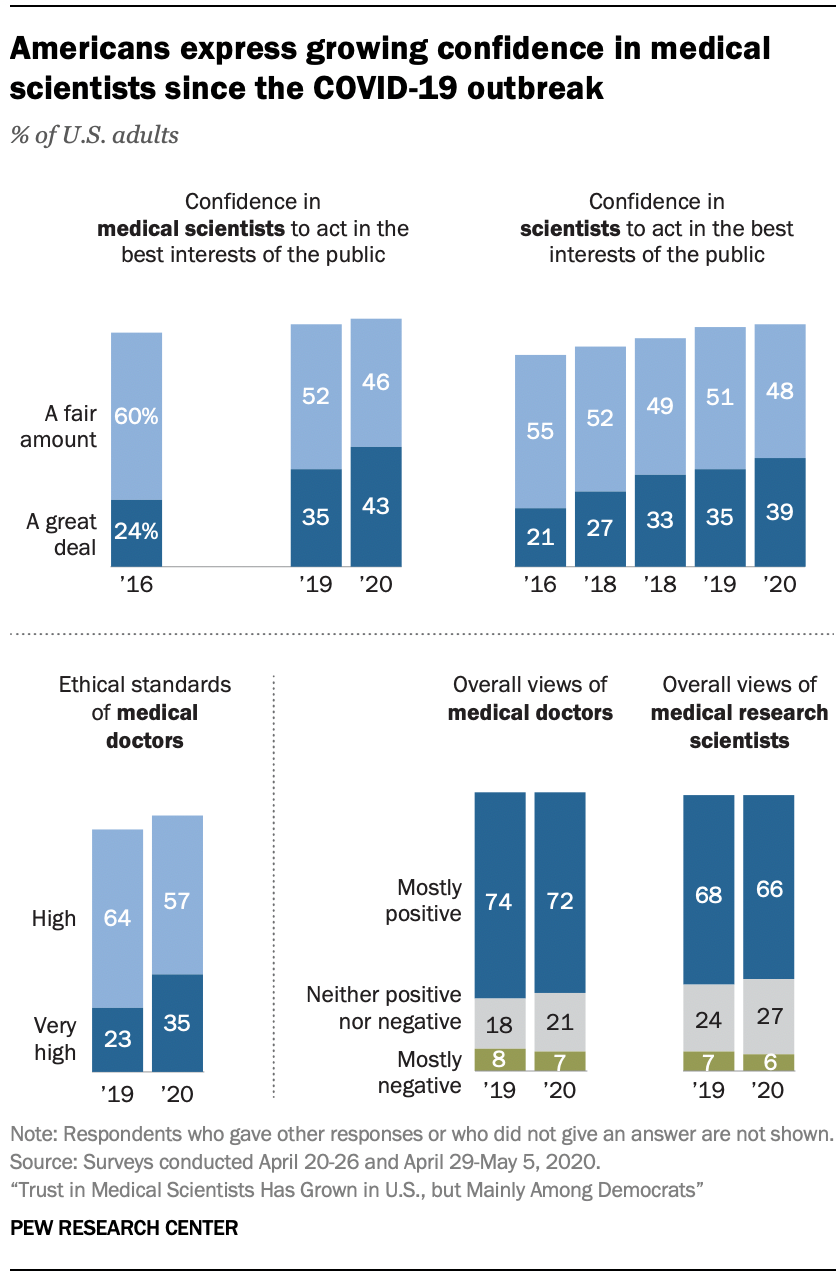

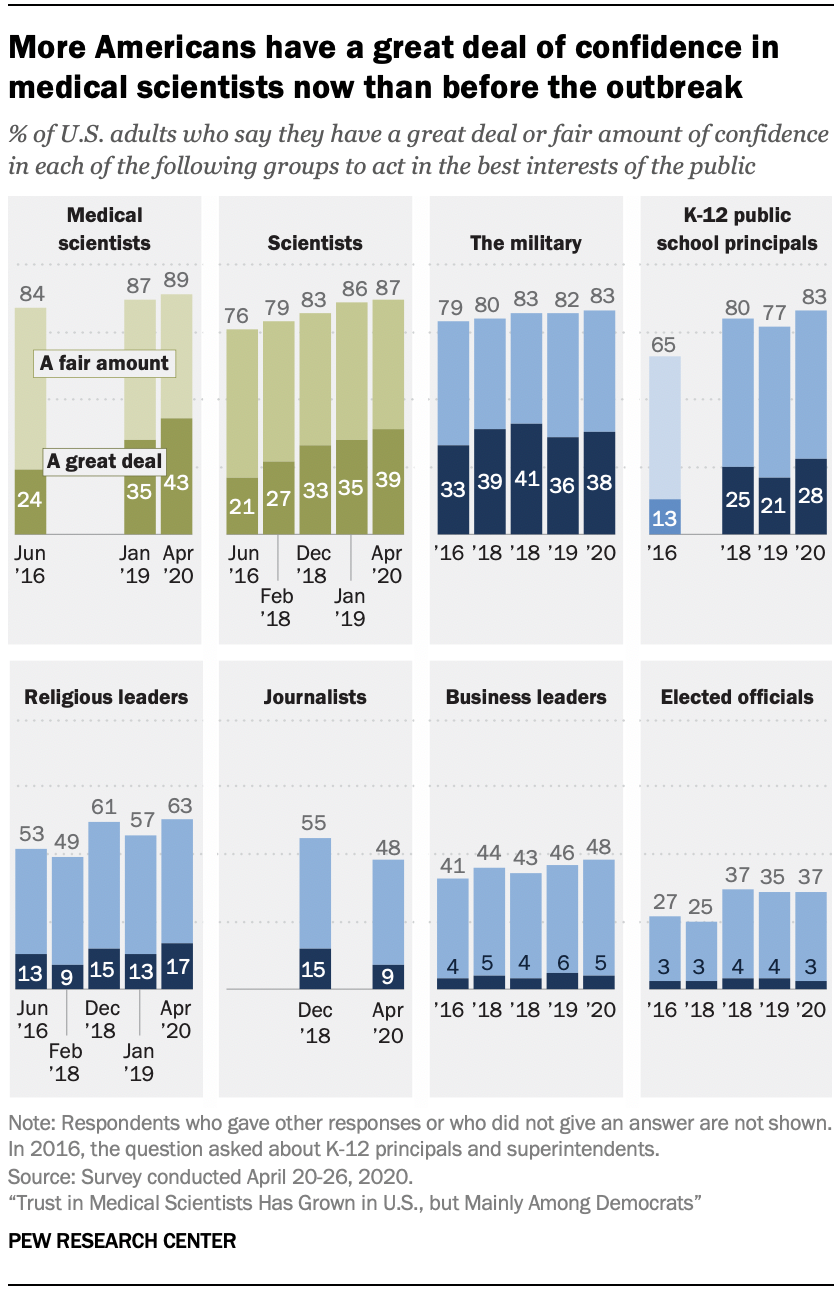

Public confidence in medical scientists to act in the best interests of the public has gone up from 35% with a great deal of confidence before the outbreak to 43% in the Center’s April survey. Similarly, there is a modest uptick in public confidence in scientists, from 35% in 2019 to 39% today. (A random half of survey respondents rated their confidence in one of the two groups.)

The rise in public confidence for scientific groups is in stark contrast with that for other groups and institutions. For example, confidence in the military has been stable over the same time period, and that for journalists has declined.

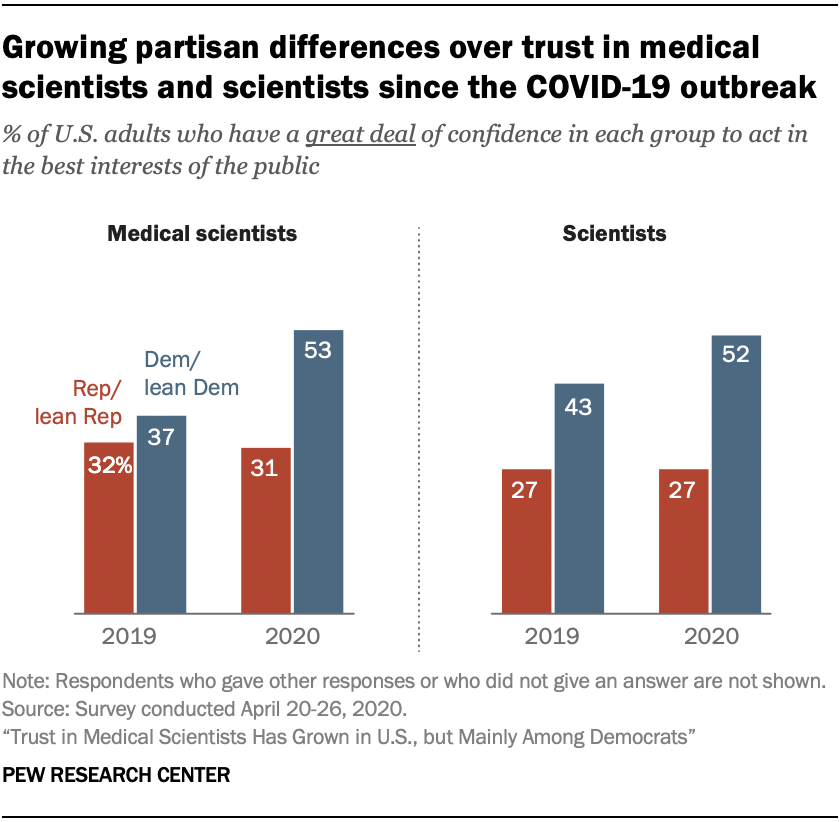

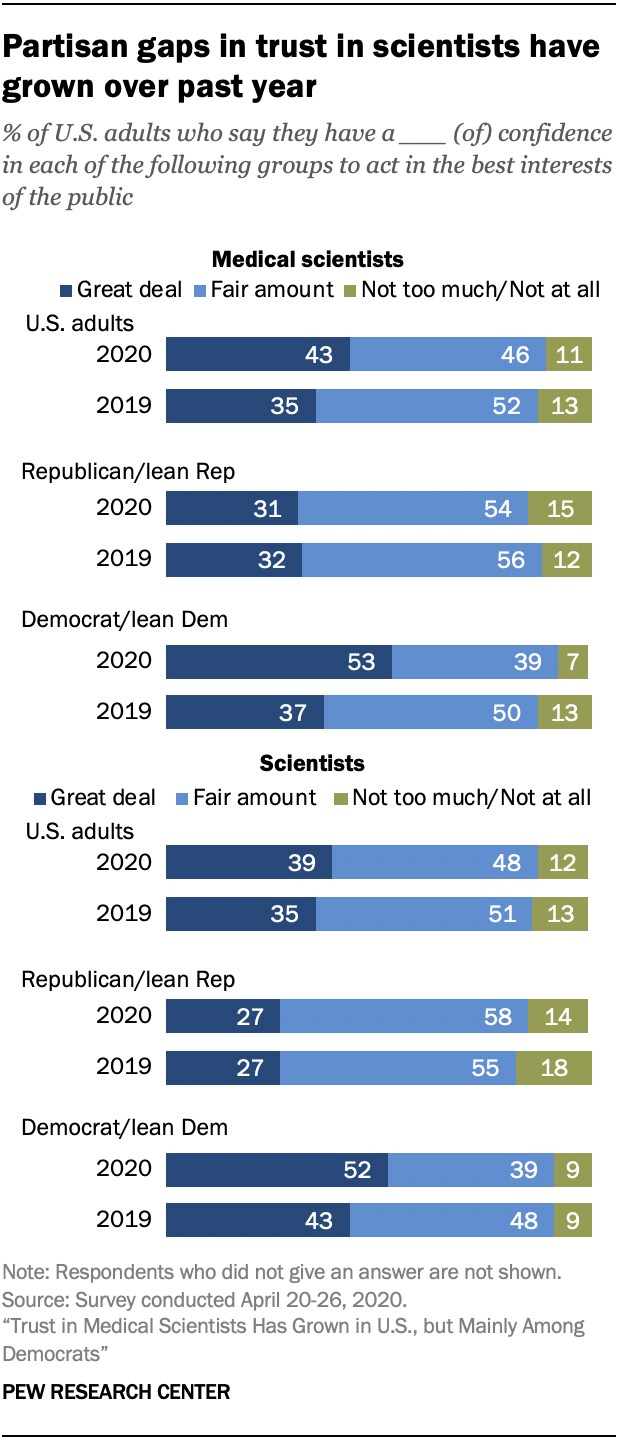

But public confidence has turned upward with Democrats, not Republicans. Among Democrats and those leaning to the Democratic Party, 53% have a great deal of confidence in medical scientists to act in the public interest, up from 37% in January 2019. But among Republicans and those who lean Republican, 31% express a great deal of confidence in medical scientists, roughly the same as in 2019 (32%). As a result, there is now a 22 percentage point difference between partisan groups when it comes to trust in medical scientists.

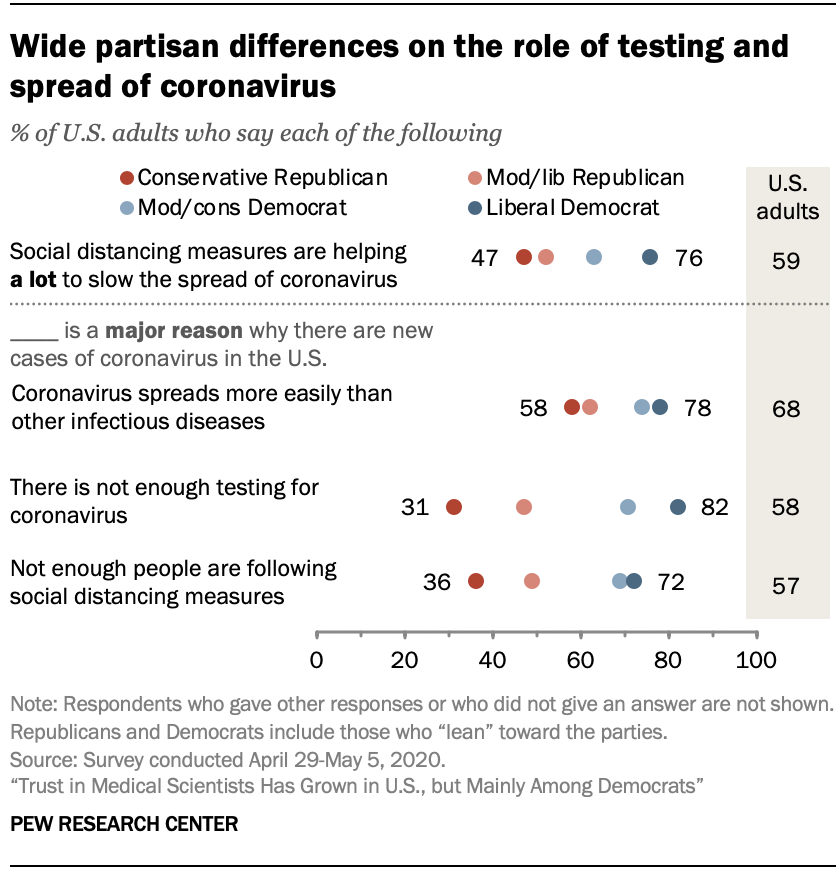

While a majority of U.S. adults (59%) believe social distancing measures are helping a lot to slow the spread of the coronavirus, Democrats are more likely to say this than Republicans (69% vs. 49%). And, when asked about possible reasons for the ongoing presence of new infections in the U.S., partisans diverge, particularly when it comes to the role of testing. Three-quarters of Democrats (75%) consider too little testing a major factor behind new disease cases in the U.S. compared with 37% of Republicans.

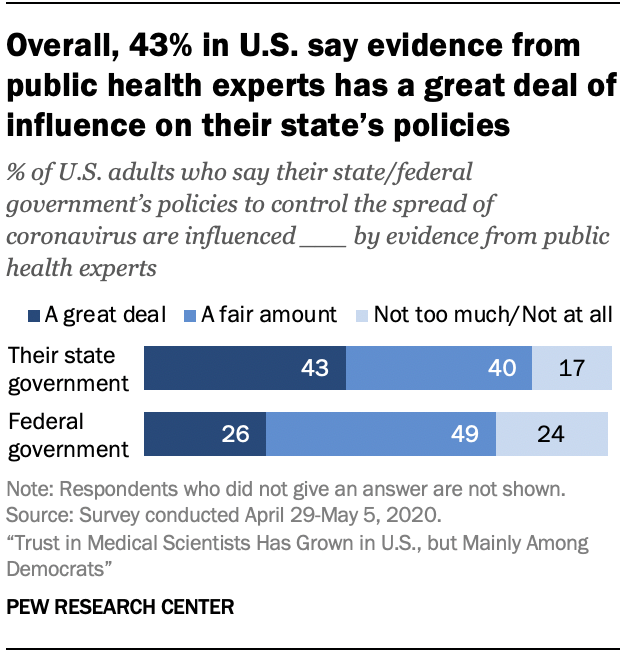

Most people believe that evidence from public health experts is influencing government policies related to the coronavirus at least a fair amount, but more think such evidence has a great deal of influence on their state’s policies (43%) than on federal policy (26%).

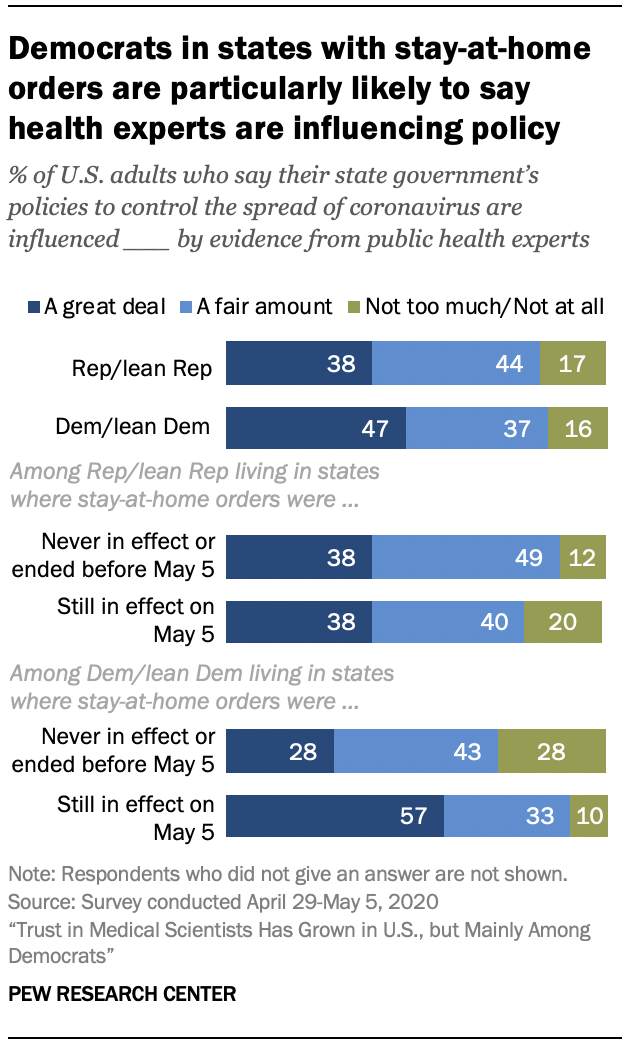

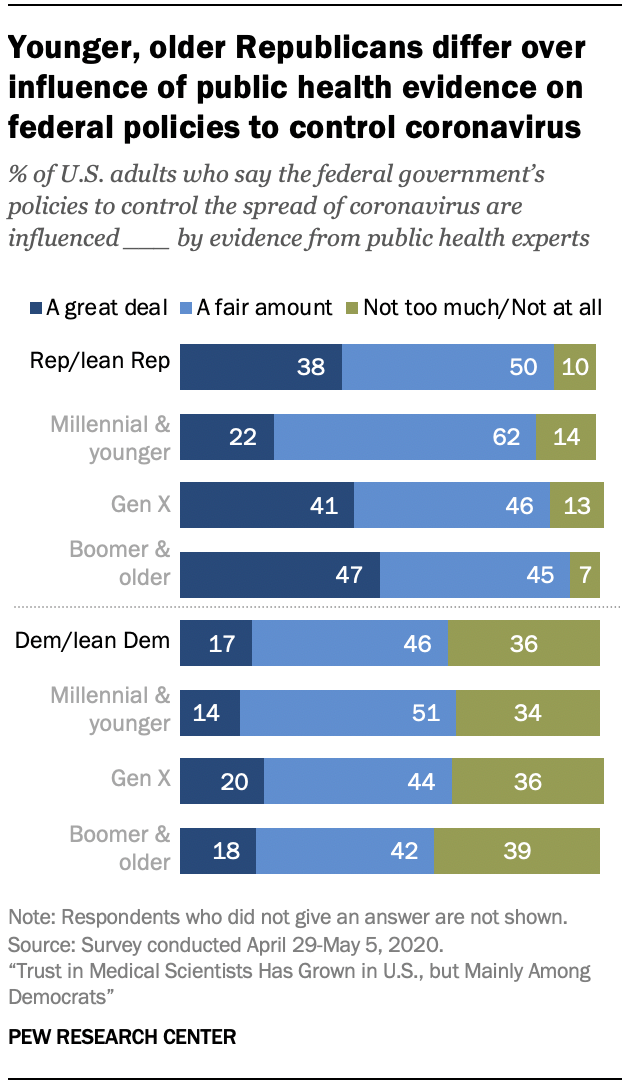

As with views on government handling of the coronavirus, partisans see the intersection of public health and policy through a different lens. For example, about twice as many Republicans (38%) as Democrats (17%) think federal policies to control the spread of the coronavirus are influenced a great deal by evidence from public health experts.

In addition, the new survey finds Democrats remain more supportive than Republicans of scientists taking an active role in science-related policy matters. But the balance of opinion has shifted among both partisan groups when it comes to the public’s role. A majority of U.S. adults now say that public opinion should not play an important role guiding science-related policy decisions “because these issues are too complex”; 55% hold this view in the new survey, up from 44% in 2019.

Most Americans believe social distancing measures are helping, but political groups have diverging perspectives on the ongoing outbreak

A majority of Americans believe social distancing measures in place across much of the country are helping reduce the spread of COVID-19 a lot, and there is widespread agreement that these measures are helping at least a little.

People attribute new cases of the coronavirus to a mix of factors. Majorities say that COVID-19’s spreading more easily than other infectious diseases (68%), not enough testing available for coronavirus (58%) and not enough people following social distancing measures (57%) are major reasons the U.S. is seeing new cases of the coronavirus.

About half or more across gender, race and ethnicity, generation and educational groups believe social distancing measures are helping a lot to reduce the spread of the coronavirus. Those with a postgraduate degree are particularly likely to see social distancing measures as helping a lot compared with those who have a high school diploma or less education (74% vs. 55%). (For details, see Appendix A.)

But there is a distinct partisan tint to how Americans see these measures and the restrictions designed to implement them around the country.

More Democrats (69%) than Republicans (49%) believe social distancing measures are helping reduce the spread of the coronavirus a lot, although strong majorities of both party groups say social distancing is helping at least a little. (Just 14% of Republicans and 8% of Democrats say social distancing measures are helping not too much or not at all.)

Political groups also differ over the reasons behind continued coronavirus infections, particularly around the roles of testing and social distancing.

Most Democrats believe that not enough testing for COVID-19 constitutes a major reason behind new infections of the disease; 82% of liberal Democrats and 71% of moderate or conservative Democrats say this. By contrast, 31% of conservative Republicans and 47% of moderate or liberal Republicans believe a lack of testing is a major reason behind new infections.

About seven-in-ten Democrats believe a major reason for new cases of coronavirus is that not enough people are following social distancing measures. About half of moderate or liberal Republicans (49%) and 36% of conservative Republicans agree that this is a major reason behind new cases of coronavirus.

But majorities of both Democrats (76%) and Republicans (59%) see the disease itself as a factor, saying a major reason behind the ongoing spread of infection is that COVID-19 spreads more easily than other infectious diseases.

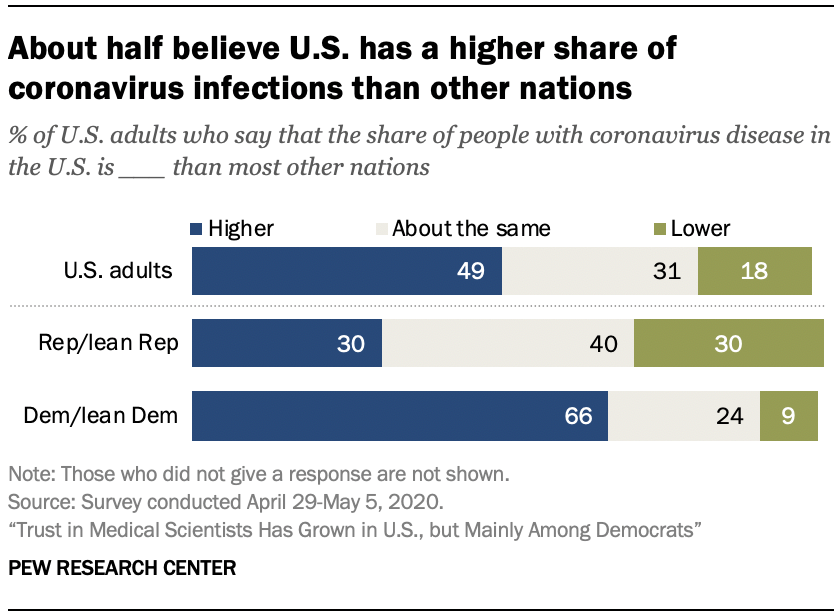

Roughly half of Americans (49%) believe the share of people with the coronavirus is higher in the U.S. than in most other nations, 18% believe the U.S. share is lower and about three-in-ten (31%) think the U.S. experience is about the same as most other nations.

It’s important to keep in mind that while such perceptions may be influenced by news and information about the spread of the disease, global statistics on the number of infections continue to change as new cases arise and classifications of infection are better identified.

More Democrats (66%, including leaners) than Republicans (30%, including leaners) think the share of people with COVID-19 is higher in the U.S. than most other nations.

Education also tends to align with beliefs on this question among Democrats, but not Republicans. About seven-in-ten Democrats with a postgraduate degree (72%) say the share of coronavirus infections is higher in the U.S. than in other nations, compared with 61% of Democrats with a high school diploma or less. But among Republicans there is no difference in views on this issue across education levels. See Appendix A for details.

For Americans’ views of how nations are handling the outbreak, see “Americans Give Higher Ratings to South Korea and Germany Than U.S. for Dealing With Coronavirus.”

Americans’ views about the role of public health in policy are tied to partisanship

Public health officials have played a prominent role in news and information about the spread of the coronavirus and ways to limit its effects on the population’s health. The Center survey asked people to gauge the degree to which evidence from such experts influenced government policy.

More than four-in-ten Americans (43%) say their state government’s policies to control the spread of the coronavirus are influenced a great deal by evidence from public health experts, 40% say such evidence has a fair amount of influence and 17% say it has not too much or no influence on their state’s policies.

In comparison, a smaller share of U.S. adults (26%) say the federal government’s policies to control the spread of the coronavirus are influenced a great deal by public health experts’ evidence. About one-quarter of Americans (24%) think such evidence does not influenced the federal government’s response too much or at all. (The survey asked a random half of respondents to gauge the role this evidence played either in federal policies and the other half to rate its role in their state government’s policies.)

Democrats’ perception of state policies depends on where they live. A majority of Democrats (57%) living in states where stay-at-home orders or other restrictions were in place as of May 5 say evidence from public health experts has a great deal of influence on their state’s policies. In contrast, 28% of Democrats living in states where restrictions were lifted by May 5 or never in place say the same.

But Republicans’ views on this issue are similar regardless of their state’s stay-at-home orders; 38% say evidence from public health experts has a great deal of influence on their state’s policies to control COVID-19.

The same Center survey also found most Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents (87%) say their greater concern is that states will lift restrictions too quickly, compared with 47% of Republicans and Republican leaners. People’s views about the need for more restrictions on public activity in their local area also depend on both partisanship and the level of restrictions in their state. (For more, see “Americans remain concerned that states will lift restrictions too quickly, but partisan differences widen.”)

Overall, 38% of Republicans say the federal government’s policies are influenced a great deal by evidence from public health experts, compared with only 17% of Democrats. Democrats are at least three times as likely as Republicans to say public health experts do not influence the federal government’s policies related to the coronavirus too much or at all (36% vs. 10%).

There are differences in perspective on this issue between younger and older Republicans. About half of Republicans in the Baby Boomer or older generations (47%) say the federal government’s policies on the spread of the coronavirus are influenced a great deal by public health experts, while only 22% of younger Republicans in the Millennial or Gen Z generations say the same.

Among Democrats, younger and older generations hold roughly similar views on this issue.

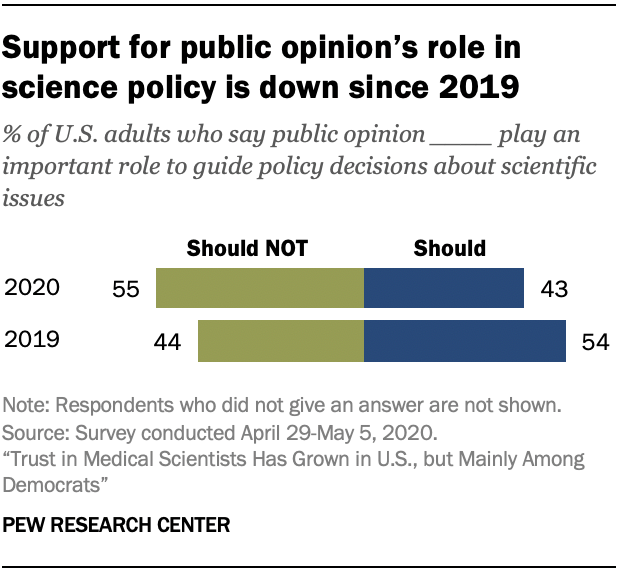

When it comes to policy about scientific issues, a majority of U.S adults (55%) say that public opinion should not play an important role “because these issues are too complex for the average person to understand,” while 43% think the public should help guide such decisions. The balance of opinion on this issue has shifted since 2019, when a Center survey found the majority (54%) said public opinion should play an important role in science policy decisions.

The shift in views about the public’s role in such matters from 2019 took place across educational and political party groups. However, Democrats shifted more on this issue (from 54% saying public opinion should play an important role in 2019 to 38% in 2020), while the Republican shift has been more modest (from 54% in 2019 to 48% in 2020).

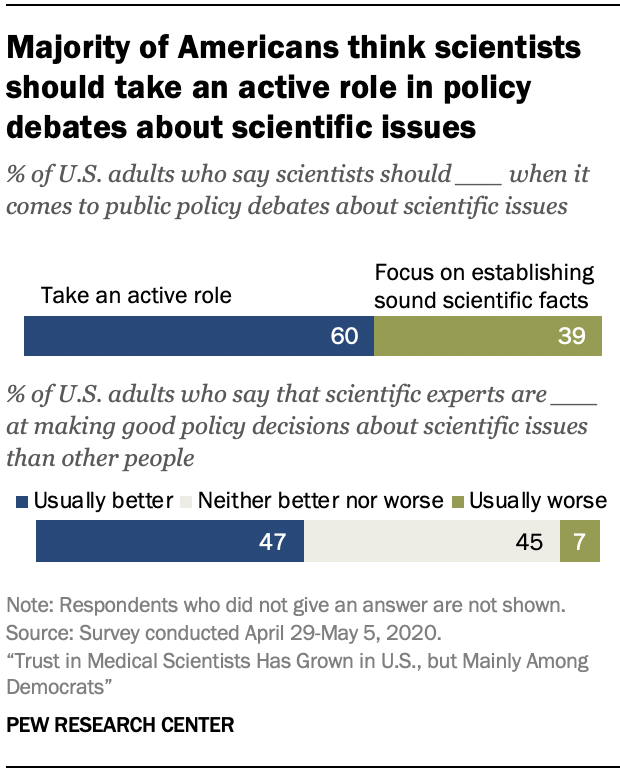

At the same time, six-in-ten Americans say in the new survey that scientists should take an active role in public policy debates, while 39% of Americans say scientists should focus on establishing scientific facts and stay out of science-related policy debates. Opinion on this issue is unchanged from last year.

Slightly fewer than half of Americans (47%) think scientific experts are usually better at making policy decisions about scientific issues than other people, a similar share as last year (45%).

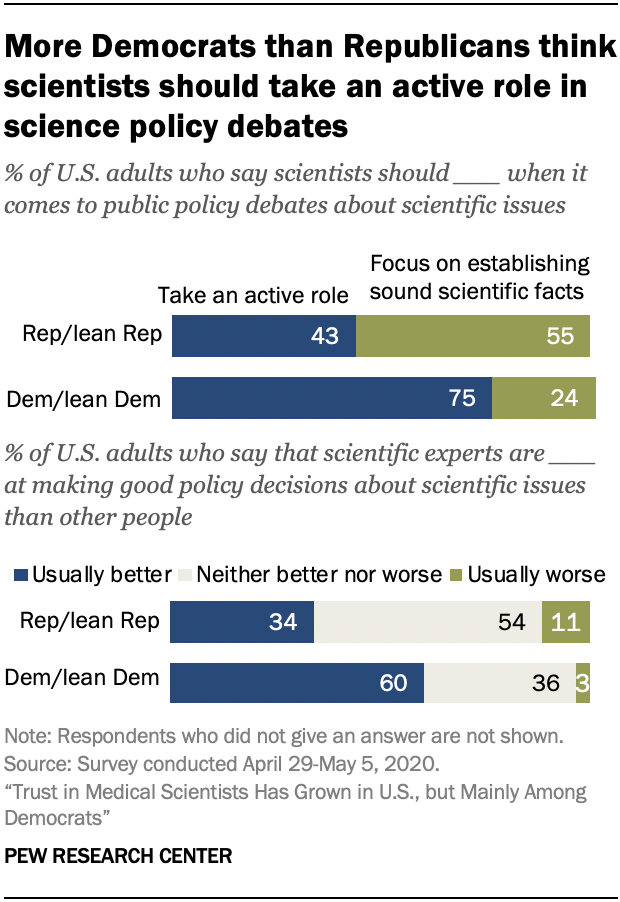

Political differences over the role and value of scientific experts remain, however. Democrats are far more likely than Republicans to think scientists should have an active role in policy debates (75% vs. 43%). Six-in-ten Democrats say scientific experts are usually better at making policy decisions about scientific issues than other people, compared with about a third of Republicans (34%). About two-thirds of Republicans (64%) think scientific experts are either worse or neither better nor worse at making science policy decisions.

Education is also linked with views about the role of scientific experts in policy matters for Democrats, but not Republicans. Among Democrats, those with a postgraduate education are more likely to say that scientists should take an active role in policy (85% compared with 64% among Democrats with a high school diploma or less education). But among Republicans there are no more than modest differences by education on this issue. See Appendix A for details. A similar pattern occurred in a 2019 survey between political party and people’s level of knowledge about science issues (based on an 11-item index of factual knowledge items) when it came to views of scientists’ judgments on policy issues.

Americans’ confidence in medical scientists is up since the coronavirus outbreak, but the rise is among Democrats, not Republicans

The Center survey finds 43% of U.S. adults express a great deal of confidence in medical scientists to act in the public interest, up 8 percentage points from 35% in 2019, prior to the outbreak. Similarly, the share with a great deal of confidence in scientists has ticked up to 39% in the new survey, from 35% in 2019.

Among eight institutions, the military receives the next highest level of public confidence (38% have a great deal of confidence in this group). Smaller shares of Americans express a great deal of confidence in other institutions such as journalists (9%) or elected officials (3%).

Confidence in medical scientists has risen among Democrats but not Republicans, leading to growing differences in trust between political groups since the coronavirus outbreak.

Just over half of Democrats and independents who lean to the Democratic Party (53%) in the April 20-26 survey report a great deal of confidence in medical scientists to act in the public interests, up from 37% in 2019. Among Republicans and Republican leaners, confidence in medical scientists has stayed roughly the same over this time period: 31% have a great deal of confidence as of April, as did 32% in 2019. As a result, there is a widening partisan divide in confidence in medical scientists from a modest 5 percentage points in 2019 to 22 points in the Center’s April survey.

There is a similar shift of public trust in scientists. Among Democrats, 52% have a great deal of confidence in scientists to act in the public interest, up from 43% in 2019. By contrast, there has been no change in Republicans’ trust: 27% have a great deal of confidence in scientists, the same as in 2019. Thus, there is a growing partisan divide when it comes to confidence in scientists. (The survey asked a random half of respondents to rate their confidence in medical scientists and the other random half to rate their confidence in scientists.)

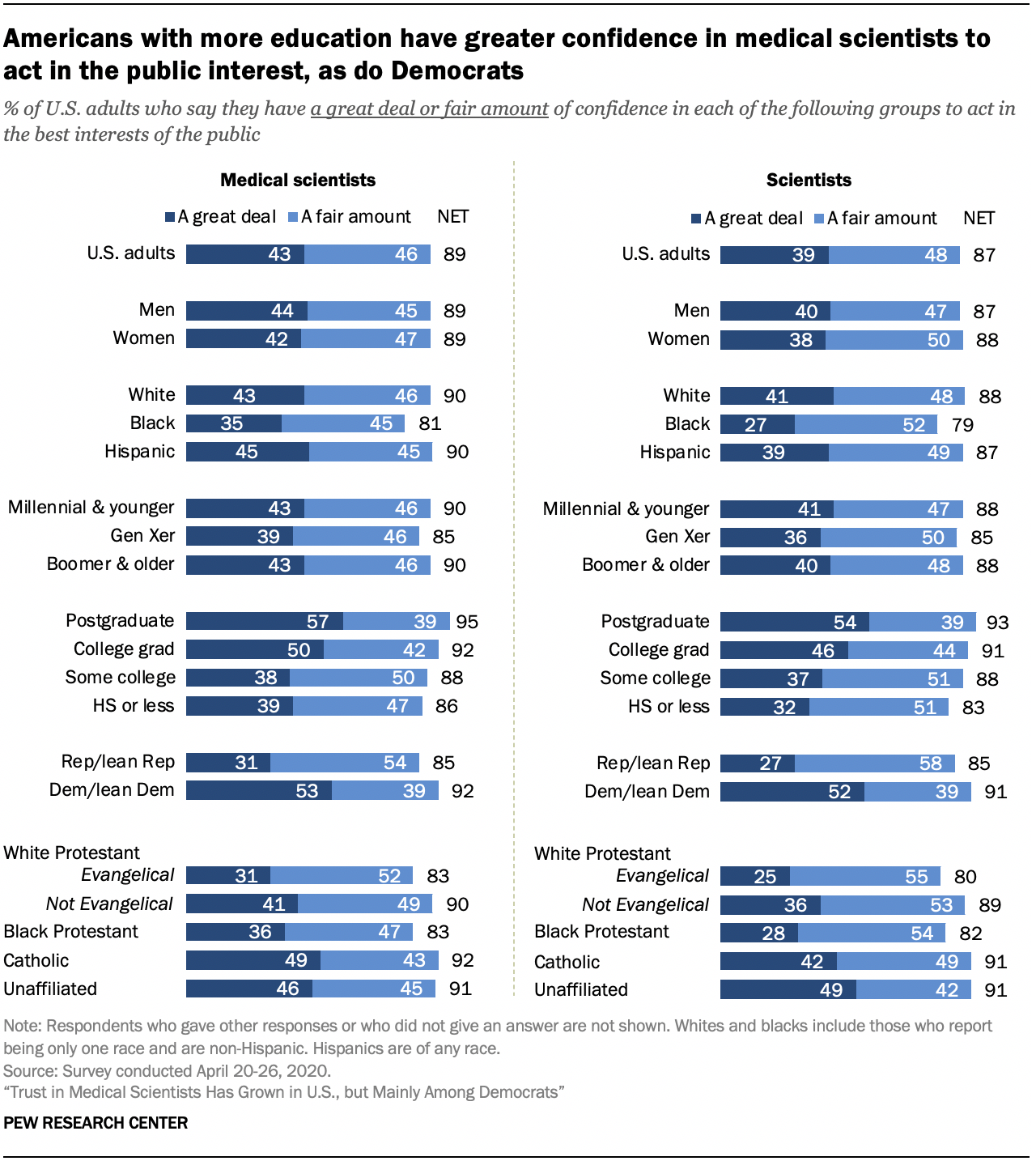

Americans with high levels of education are more likely to have strong confidence in medical scientists. There is a similar correlation between education and confidence in scientists.

However, the role of education in people’s level of confidence in scientists depends on political party. Seven-in-ten Democrats with a postgraduate degree (70%) have a great deal of confidence in scientists to act in the public interest, compared with 40% of those with a high school diploma or less education. Among Republicans, there is no such pattern; 27% of those with postgraduate degree and the same share of those a high school diploma or less have a great deal of confidence in scientists (27%). See Appendix A for details.

A 2019 Center report showed that people with higher levels of factual knowledge about science, based on an 11-item index, tend to express more confidence in scientists to act in the public interest. There, too, science knowledge was linked with Democrats’ confidence in scientists but not Republicans’ confidence.

On average, white evangelical Protestants are less likely than non-evangelical Protestants to have a great deal of trust in medical scientists (31% vs. 41%, respectively) and scientists (25% vs. 36%). These differences remain even after controlling for party identification and education.

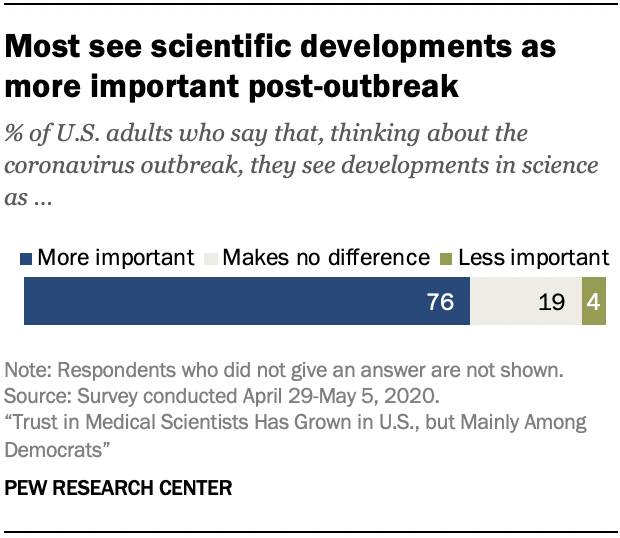

A majority of Americans (76%) say they see scientific developments as more important since the coronavirus outbreak. Just 4% say they see such developments as less important, and another 19% say the outbreak has made no difference in the level of importance.

Partisan differences also emerge in these perspectives, with 84% of Democrats and 66% of Republicans saying they see developments in science as more important in light of the coronavirus outbreak. (See Appendix A for details.)

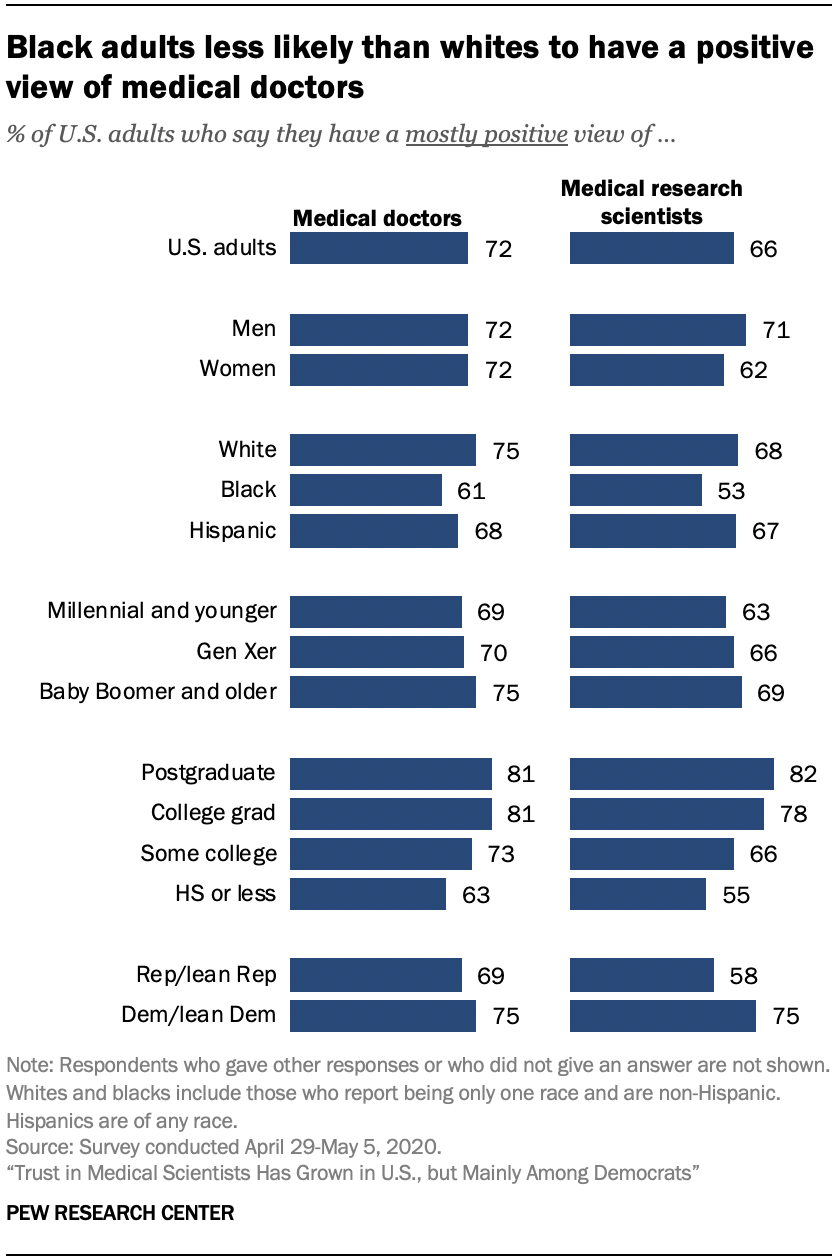

White adults are more likely than black adults to have a positive overall view of medical doctors and medical research scientists

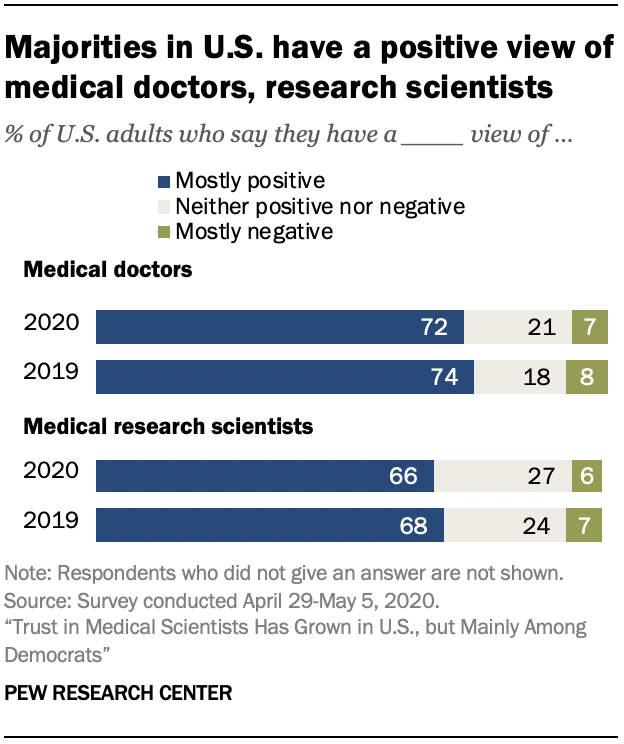

Overall, a majority of Americans say they have a mostly positive view of medical doctors (72%), and the same is true for medical research scientists (66%). Views of these scientists have not changed substantially since the question was last asked in January 2019, before the COVID-19 outbreak.

Americans with a bachelor’s or postgraduate degree (both 81%) are more likely than adults who attended some college (73%) or who have a high school diploma or less (63%) to have positive overall opinions of medical doctors. A similar education pattern exists for opinions of medical researchers.

White adults (75%) are more likely than black adults (61%) to have a positive view of medical doctors. Black Americans also stand out for their lower ratings of medical research scientists: About half (53%) have a positive view, compared with majorities of white (68%) and Hispanic (67%) adults.1

There are partisan differences in overall views of medical professionals. Democrats (75%) are more likely than Republicans (58%) to have mostly positive views of medical research scientists. Democrats are also slightly more likely to say they have positive views of doctors (75%, vs. 69% of Republicans). In a 2019 Center survey, Republicans and Democrats were about equally likely to have positive views of doctors (77% and 73%, respectively).

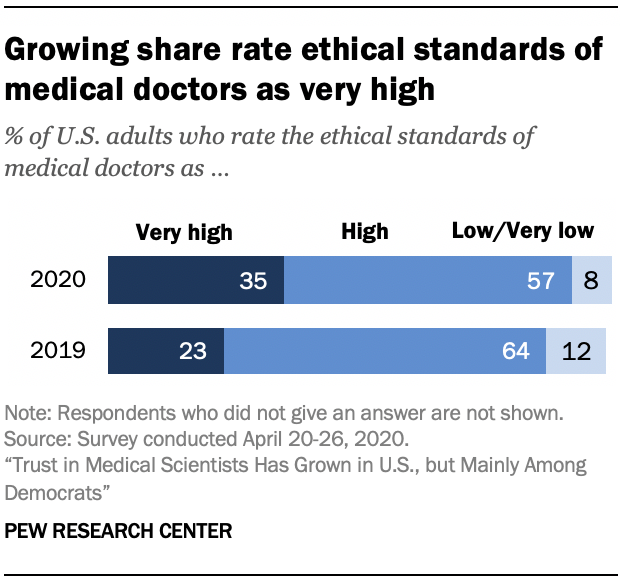

A growing share of Americans describe doctors’ ethical standards as very high

Overall, 35% of U.S. adults say medical doctors have very high ethical standards, up from 23% in a 2019 Center survey.

Ratings of doctors’ ethics are up across all demographic groups. See Appendix A for details.

While “very high” ratings are up significantly among both parties since 2019, Democrats (39%) are more likely than Republicans (31%) to rate doctors’ ethical standards as very high.

In addition, people with a postgraduate education (40%) are more likely than those who attended some college or high school or less to rate doctors’ ethical standards as very high (34% each).

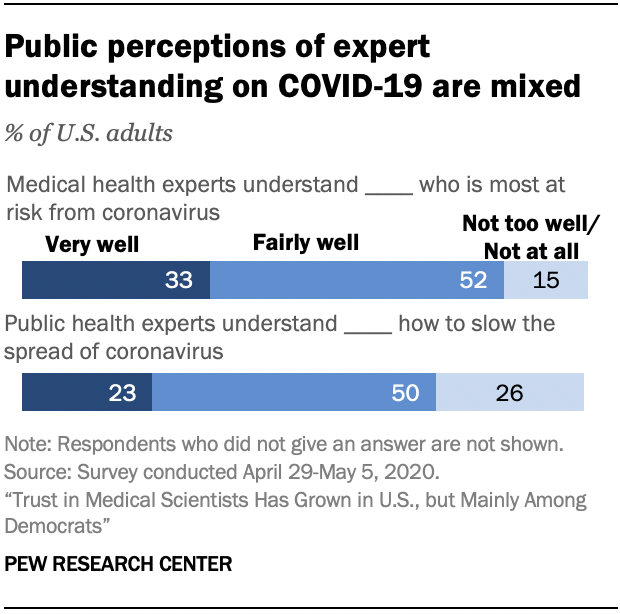

But Americans are more tepid when it comes to rating how well medical experts understand specific issues in the coronavirus crisis.

One-third of U.S. adults say medical health experts understand very well who is most at risk for serious illness from the coronavirus, and about half (52%) say they understand who is at risk fairly well. Another 15% say that medical health experts understand who is most at risk from COVID-19 not too or not at all well.

Assessments of public health experts are lower by comparison. Roughly one-quarter (23%) of U.S. adults say public health experts understand how to slow the spread of the coronavirus very well, half think public health experts understand this fairly well and another 26% say experts understand this not too or not at all well.

More Democrats than Republicans rate the understanding of experts in these areas highly. For example, 37% of Democrats (including leaners) and 29% of Republicans (including leaners) say medical health experts understand very well who is most at risk from the coronavirus disease. About three-in-ten Democrats (31%) say public health experts understand very well how to slow the spread of COVID-19, compared with about half as many Republicans (15%).