Barack Obama campaigned for the U.S. presidency on a platform of change. As he prepares to leave office, the country he led for eight years is undeniably different. Profound social, demographic and technological changes have swept across the United States during Obama’s tenure, as have important shifts in government policy and public opinion.

Apple released its first iPhone during Obama’s 2007 campaign, and he announced his vice presidential pick – Joe Biden – on a two-year-old platform called Twitter. Today, use of smartphones and social media has become the norm in U.S. society, not the exception.

The election of the nation’s first black president raised hopes that race relations in the U.S. would improve, especially among black voters. But by 2016, following a spate of high-profile deaths of black Americans during encounters with police and protests by the Black Lives Matter movement and other groups, many Americans – especially blacks – described race relations as generally bad.

The U.S. economy is in much better shape now than it was in the aftermath of the Great Recession, which cost millions of Americans their homes and jobs and led Obama to push through a roughly $800 billion stimulus package as one of his first orders of business. Unemployment has plummeted from 10% in late 2009 to below 5% today; the Dow Jones Industrial Average has more than doubled.

But by some measures, the country faces serious economic challenges: A steady hollowing of the middle class, for example, continued during Obama’s presidency, and income inequality reached its highest point since 1928.

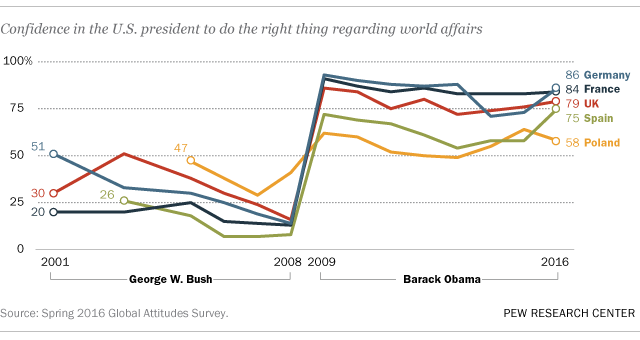

Obama’s election quickly elevated America’s image abroad, especially in Europe, where George W. Bush was deeply unpopular following the U.S. invasion of Iraq. In 2009, shortly after Obama took office, residents in many countries expressed a sharp increase in confidence in the ability of the U.S. president to do the right thing in international affairs. While Obama remained largely popular internationally throughout his tenure, there were exceptions, including in Russia and key Muslim nations. And Americans themselves became more wary of international engagement.

Views on some high-profile social issues shifted rapidly. Eight states and the District of Columbia legalized marijuana for recreational purposes, a legal shift accompanied by a striking reversal in public opinion: For the first time on record, a majority of Americans now support legalization of the drug.

As it often does, the Supreme Court settled momentous legal battles during Obama’s tenure, and in 2015, it overturned long-standing bans on same-sex marriage, effectively legalizing such unions nationwide. Even before the court issued its landmark ruling in Obergefell v. Hodges, a majority of Americans said for the first time that they favored same-sex marriage.

As the Obama era draws to a close, Pew Research Center looks back on these and other important social, demographic and political shifts that have occurred at home and abroad during the tenure of the 44th president. And we look ahead to some of the trends that could define the tenure of the 45th, Donald Trump.

[chapter title=”Who we are” background_image=”286528″]

Demographic changes don’t happen quickly. Obama’s presidency is only a chapter in a story that began long before his arrival and will continue long after his departure. Even so, the U.S. of today differs in some significant ways from the U.S. of 2008.

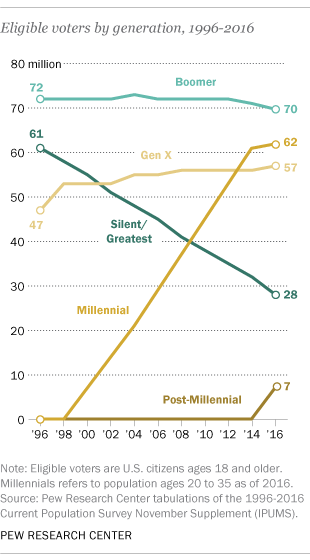

Millennials are approaching Baby Boomers as the nation’s largest living adult generation and as the largest generation of eligible voters.

The nation’s growing diversity has become more evident, too. In 2013, for the first time, the majority of newborn babies in the U.S. were racial or ethnic minorities. The same year, a record-high 12% of newlyweds married someone of a different race.

The November electorate was the country’s most racially and ethnically diverse ever. Nearly one-in-three eligible voters on Election Day were Hispanic, black, Asian or another racial or ethnic minority, reflecting a steady rise since 2008. Strong growth in the number of Hispanic eligible voters, in particular U.S.-born youth, drove much of this change. Indeed, for the first time, the Hispanic share of the electorate is now on par with the black share.

While illegal immigration served as a flashpoint in the tumultuous campaign to succeed Obama, there has been little change in the number of unauthorized immigrants living in the U.S. since 2009. And for the first time since the 1940s, more Mexican immigrants – both legal and unauthorized – have returned to Mexico from the U.S. than have entered.

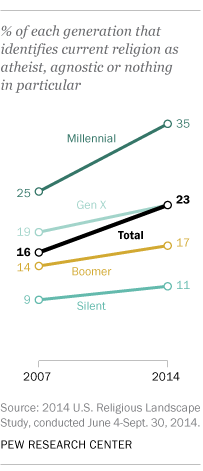

When it comes to the nation’s religious identity, the biggest trend during Obama’s presidency is the rise of those who claim no religion at all. Those who self-identify as atheists or agnostics, as well as those who say their religion is “nothing in particular,” now make up nearly a quarter of the U.S. adult population, up from 16% in 2007.

Christians, meanwhile, have fallen from 78% to 71% of the U.S. adult population, owing mainly to modest declines in the share of adults who identify with mainline Protestantism and Catholicism. The share of Americans identifying with evangelical Protestantism, historically black Protestant denominations and other smaller Christian groups, by contrast, have remained fairly stable.

Due largely to the growth of those who don’t identify with any religion, the shares of Americans who say they believe in God, consider religion to be very important in their lives, say they pray daily and say they attend religious services at least monthly have all ticked downward in recent years. At the same time, the large majority of Americans who do identify with a faith are, on average, as religiously observant as they were a few years ago, and by some measures even more so.

The tide of demographic changes in the U.S. has affected both major parties, but in different ways. Democratic voters are becoming less white, less religious and better-educated at a faster rate than that of the country, while Republicans are aging more quickly than the country as a whole. Education, in particular, has emerged as an important dividing line in recent years, with college graduates becoming more likely to identify as Democrats and those without a college degree becoming more likely to identify as Republicans.

[chapter title=”What we believe” background_image=”286530″]

More politically divided

Trump defeated Democrat Hillary Clinton in November’s bitterly contested election, becoming the first person ever to win the White House with no prior political or military experience. But the divisions that emerged during the campaign and in its aftermath had been building long before Trump announced his candidacy, and despite Obama’s stated aim of reducing partisanship.

Partisan divisions in assessments of presidential performance, for example, are wider now than at any point going back more than six decades, and this growing gap is largely the result of increasing disapproval of the chief executive from the opposition party. An average of just 14% of Republicans have approved of Obama over the course of his presidency, compared with an average of 81% of Democrats.

Obama’s signature legislative achievement – the 2010 health care law that informally bears his name – has prompted some of the sharpest divisions between Democrats and Republicans. About three-quarters of Democrats approve of the Affordable Care Act, or “Obamacare,” while 85% of Republicans disapprove of it.

But the partisanship so evident during Obama’s years is perhaps most notable because it extended far beyond disagreements over specific leaders, parties or proposals. Today, more issues cleave along partisan lines than at any point since surveys began to track public opinion.

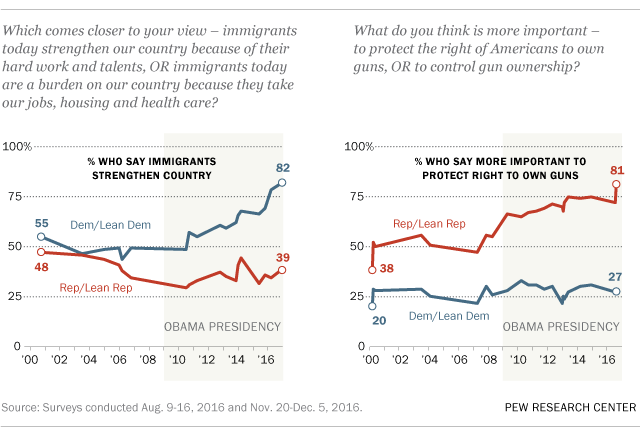

Between 1994 and 2005, for example, Republicans’ and Democrats’ attitudes toward immigrants in the U.S. tracked one another closely. Beginning around 2006, however, they began to diverge. And the gap has only grown wider since then: Democrats today are more than twice as likely as Republicans to say that immigrants strengthen the country.

Gun control has long been a partisan issue, with Democrats considerably more likely than Republicans to say it is more important to control gun ownership than protect gun rights. But what was a 27-percentage-point gap between supporters of Obama and John McCain on this question in 2008 surged to a historic 70-point gap between Clinton and Trump supporters in 2016.

Climate change marks another area where the parties are deeply divided. Wide partisan divides stretch from the causes and cures for climate change to trust in climate scientists and their research. Only about a fifth of Republicans and independents who lean Republican say they trust climate scientists “a lot” to give full and accurate information about the causes of climate change. This compares with more than half of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents.

Skeptical of government, other institutions

If views of some issues changed markedly during Obama’s time in office, views of the government did not. Americans’ trust in the federal government remained mired at historic lows. Elected officials were held in such low regard, in fact, that more than half of the public said in a fall 2015 survey that “ordinary Americans” would do a better job of solving national problems.

Americans felt disillusioned with the way Washington responded to the financial meltdown of 2008. In 2015, seven-in-ten Americans said that the government’s policies following the recession generally did little or nothing to help middle-class people. A roughly equal share said the government’s post-recession policies did a great deal or a fair amount to help large banks and financial institutions.

Against a backdrop of global terrorism – including several attacks on American soil – Americans also became less confident in the ability of their government to handle threats. In 2015, following major attacks in Paris and San Bernardino, California, the public’s concerns about terrorism surged and positive ratings of the government’s handling of terrorism plummeted to a post-9/11 low.

Americans also had serious concerns about privacy, though the government was not the sole focus of skepticism in this respect. During the Obama years, Americans were highly skeptical their personal information would remain private and secure, regardless of whether it was the government or the private sector that collected it. In a 2014 survey, fewer than one-in-ten Americans said they were very confident that each of 11 separate entities – ranging from credit card companies to email providers – would keep their records private and secure.

[chapter title=”Our place in the world” background_image=”286534″]

Obama’s election provided an almost immediate boost to America’s global image following the Bush administration and its entanglements in the Middle East. Americans themselves, however, grew more wary of international engagement during Obama’s presidency.

In Germany, favorability of the U.S. more than doubled following Obama’s election. In the United Kingdom, confidence in the U.S. president surged from 16% for Bush in 2008 to 86% for Obama in 2009. The Obama bump was most dramatic in Western Europe, but was also evident in virtually every country surveyed between 2007 and 2009.

The U.S. retained its popularity in Africa and parts of Latin America during Obama’s second term. But the U.S. wasn’t seen favorably everywhere. Russian views of the U.S. veered sharply negative in 2014 while the image of the U.S. remained dour in key Muslim countries. Meanwhile, certain U.S. actions under Obama, such as drone strikes, eavesdropping on foreign leaders and revelations of torture in the post-9/11 period, were globally unpopular.

Americans, meanwhile, have become less certain of their place in the world. The share of Americans who say it would be better if the U.S. just dealt with its own problems and let other countries deal with their own as best they can has risen 11 points since the spring of 2010.

The public’s wariness toward global engagement extends to U.S. participation in the global economy and international trade agreements. Roughly half of Americans say U.S. involvement in the global economy is a bad thing because it lowers wages and costs jobs; fewer see it as a good thing because it provides the U.S. with new markets and opportunities for growth. Americans’ views of trade agreements have also soured, a shift driven almost entirely by increasingly negative views among Republicans, especially during the campaign of Trump, who has been highly critical of free trade agreements.

About half of Americans say the U.S. is a less powerful and important world leader than it was a decade ago, though most still believe the U.S. is the world’s leading economic and military power.

[chapter title=”How we interact” background_image=”286549″]

Smartphones and social media

If demographic changes are slow, technological changes can be swift. In the new millennium, major technology revolutions have occurred in broadband connectivity, social media use and mobile adoption. All three of them continued, and in some cases accelerated, during Obama’s presidency.

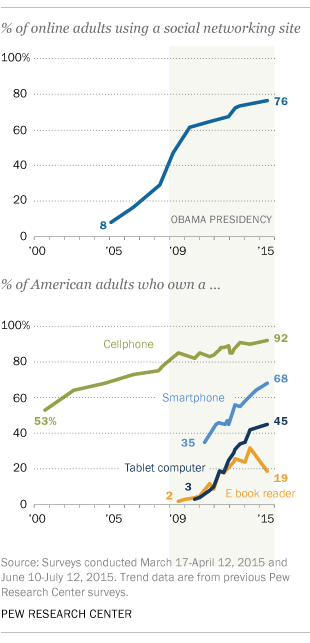

More than two-thirds of Americans owned a smartphone by 2015, six times the ownership levels at the dawn of Obama’s tenure. When Apple released the iPad halfway through Obama’s first term, a mere 3% of Americans owned tablets; nearly half had tablets by the end of 2015.

Although social media use was a signature aspect of Obama’s 2008 campaign, only one-third of Americans used social media that year. With the rise of Facebook, Twitter and other apps, social media use climbed to about three-quarters of online adults by 2015.

Obama also helped usher in the rise of digital video in politics, sharing his weekly address through the White House YouTube channel. By the end of his second term, YouTube had become a media behemoth with over a billion users.

How we get our news

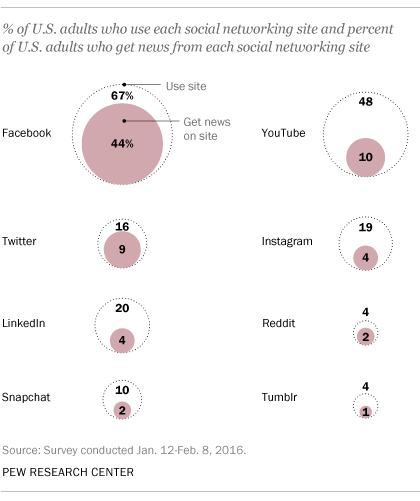

The rise of digital tools and social platforms has also helped bring about profound changes in the U.S. media landscape. Americans today access information, get news and engage with politicians in new and different ways than in 2008 – a trend underscored by the political success of Trump, whose frequent use of Twitter to communicate directly with supporters (and detractors) was one of the defining narratives of his campaign to succeed Obama.

In 2016, more U.S. adults learned about the presidential election through social media than through print newspapers. Younger Americans, in particular, were more likely to turn to social media rather than more traditional platforms, with those ages 18 to 29 listing it as their “most helpful” source for election information in a January 2016 survey. (Cable TV, by contrast, remained among the most helpful sources for all other adults.)

The overall American news experience changed significantly during Obama’s years in office. In 2008, relatively few Americans said they got their news through social media or via a smartphone or other mobile device. By 2016, six-in-ten Americans said they got their news through social media and seven-in-ten said they accessed it through a mobile device.

Print newspapers continued a long-term decline, with sharp cuts in newspaper staffing and a severe dip in average circulation. Newspaper editorial staff in the U.S. went from nearly 47,000 in 2008 to about 33,000 in 2014 – a 30% drop, according to data from the American Society of News Editors.

While television remains a major source of news for Americans, there are signs of change. Viewership of local TV newscasts has been flat or declining for years, depending on the time of day. Between 2007 and 2015, average viewership for late-night newscasts declined 22%, according to analysis of Nielsen Media Research data.

Overall, Americans remained extremely wary of the news media. In a 2016 survey, seven-in-ten adults said the media has a “negative effect” on the way things are going in the U.S. today – the highest share of any nongovernmental institution polled. Nearly three-quarters said in a separate survey that the news media are biased.

But for all the skepticism facing the media, Americans continued to value the watchdog functions of the press. About eight-in-ten registered voters, for example, said it is the news media’s responsibility to fact-check political candidates and campaigns. Three-in-four said that news organizations keep political leaders from doing things they shouldn’t.

The future of the media is likely to be an even more salient question following the 2016 presidential campaign, which saw the emergence of a trend of “fake news” that has caused some observers to say that America has entered a period of “post-truth politics.”

[chapter title=”Looking ahead” background_image=”286550″]

While the 2016 election may be one for the history books, looking ahead requires equal measures of caution and humility, particularly when it comes to politics and public policy.

It remains to be seen, for example, whether Donald Trump will push forward on some of his highest-profile campaign priorities, such as constructing a wall on the U.S. border with Mexico, lowering federal taxes and reducing government regulation. On some of his priorities, Trump appears to have the support of the public; on others, he appears to be out of step with public sentiment. Either way, history suggests that opinion can change significantly as general proposals move to concrete legislation.

Still, there are certain bigger trends we know are going to continue and others that show no signs of reversing.

The technological changes that were such a hallmark of Obama’s eight years will go on, constantly reshaping the way we communicate, the way we travel, the way we shop and the way we work, among many other facets of everyday life. Americans seem to expect major changes: More than six-in-ten, for example, believe that within 50 years, robots or computers will do much of the work that is currently done by humans.

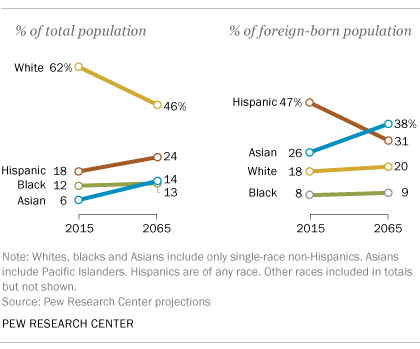

The demographic changes that have taken hold across the U.S. will continue their transformation of America, too. The nation as a whole will turn grayer and its racial and ethnic diversification is expected to continue: In less than 40 years, the U.S. will not have a single racial or ethnic majority group, according to Pew Research Center projections.

The U.S. has also long been home to more immigrants than any other country in the world, and by 2065, one-in-three Americans will be an immigrant or have immigrant parents, compared with about one-in-four today.

The nation’s stark partisan fissures are likely to persist and may deepen. Just as Obama’s job approval ratings are deeply divided along partisan lines, the public’s ratings for how Trump has handled his transition to the White House are more divided by party than they were for recent presidents-elect. A reality of American politics today is that one of the only things large numbers of Republicans and Democrats can agree on is that they can’t agree on basic facts.

The foreign policy challenges facing this politically fractured nation seem endless, from Russia and China to terrorism and the environment. At home, financial prosperity – even stability – feels increasingly out of reach to many Americans: Today, far more people are pessimistic than optimistic about life for the next generation of Americans.

Yet the United States enters this uncertain new era with undeniable, if often overlooked, strengths. Republicans and Democrats, for example, differ dramatically over whether the nation has gotten more or less powerful as a global leader over the past decade, but majorities in both parties say the U.S. is still the world’s leading military – and yes, economic – power. And most Americans say that one of the hallmarks of U.S. society – its racial and ethnic diversity – makes the country a better place to live.

It is tempting to believe that the pace of change in the U.S. has never been greater, or that 2016’s election is of greater consequence than others. As significant as the current moment of transition is, however, only the passage of time can reveal the trends that will truly have lasting importance.

Note: The second paragraph of the “Who we are” section of this essay and its accompanying graphic were updated on May 21, 2018. The changes reflect the Center’s revised definition of the Millennial generation and the updated year in which Millennials become the largest generation in the U.S. and in the American electorate.

Michael Dimock is the president of Pew Research Center, where he leads a domestic and international research agenda to explain public attitudes, demographic changes and other trends over time. A political scientist by training, Dimock has been at the Center since 2000 and has co-authored several of its landmark research reports, including studies of trends in American political and social values and a groundbreaking examination of political polarization within the American public.