Asian Americans are often seen by others as foreigners, regardless of their citizenship status or how long they or their family have lived in the U.S. This is commonly known as the “forever foreigner” or “perpetual foreigner” stereotype.

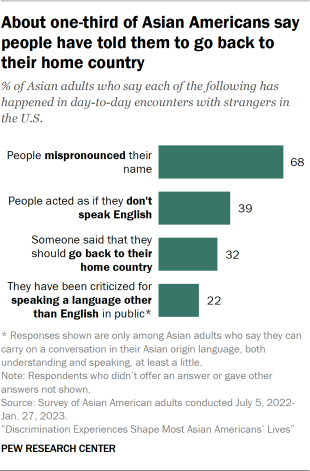

In the survey, we asked Asian adults whether they had experiences where people likely treated them as if they were a foreigner. About eight-in-ten Asian Americans (78%) have experienced at least one of the following incidents in their day-to-day encounters with strangers in the U.S.:

- 68% of Asian adults say people have mispronounced their name.

- 39% say people have acted as if they didn’t speak English.

- 32% say people have told them to go back to their “home country.”

- 22% of Asian adults who can speak the language of their Asian origin country say people have criticized them for speaking a language other than English in public.

What is the ‘forever foreigner’ stereotype?

A common experience for Asian Americans (and some other groups with large immigrant populations) is being asked when meeting someone for the first time, “Where are you from?” with a follow-up question if the person asking isn’t satisfied, “Where are you really from?” While these questions may be asked with good intentions, some Asian Americans say it makes them feel like they do not belong in the U.S., even though they may be longtime residents, citizens of the United States or even were born in the country.

Scholars have called this experience and the beliefs that may be behind it the “forever foreigner” or “perpetual foreigner” stereotype. This stereotype follows a long history of Asian Americans being excluded and treated as outsiders to American society and culture, and makes the group more likely to be affected by geopolitical tensions. The treatment of Asian Americans as proxies for foreign countries – including the incarceration of Japanese Americans after World War II, the murder of Vincent Chin, the backlash after the Sept. 11 attacks, and the spike in anti-Asian discrimination following the COVID-19 outbreak, among other examples – illustrates how “forever foreigner” narratives can be used to fuel discrimination.

Experiences with name mispronunciation

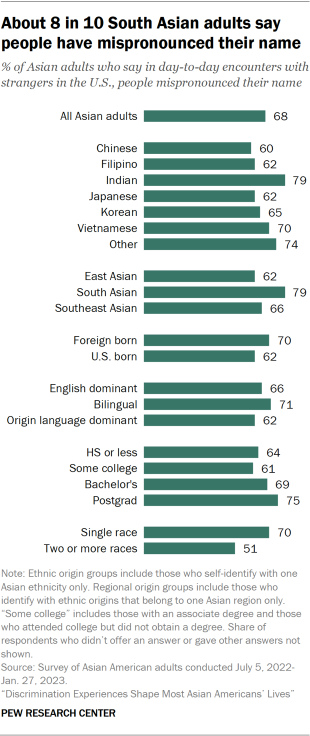

Roughly two-thirds of Asian adults (68%) say a stranger has mispronounced their name during day-to-day encounters.

While majorities across most demographic groups say they have experienced this, there are some differences, including by origin, nativity, education, race and religion:

- Ethnic origin: 79% of Indian adults say a stranger has mispronounced their name, a higher share than among other ethnic origin groups.

- Nativity: 70% of Asian immigrants say they have had this experience, compared with 62% of U.S.-born Asian adults.

- Education: 75% of Asian adults with a postgraduate degree say strangers have mispronounced their name. Somewhat smaller majorities among those with a bachelor’s degree or less say the same.

- Race: Name mispronunciation is less common among Asian adults who identify with two or more races (those who identify as Asian and at least one other race), though about half (51%) say it has happened to them. By comparison, 70% of single-race Asian adults (those who identify as Asian and no other race) say the same.

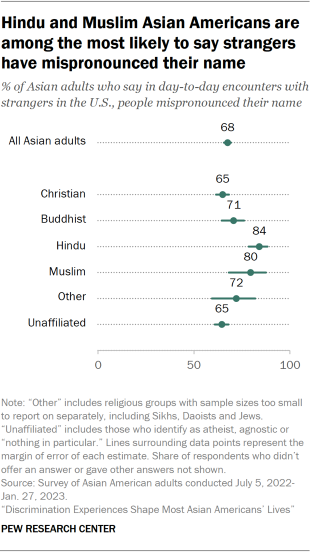

- Religion: Asian American Christians are less likely than Asian adults who are Hindu or Muslim to say people have mispronounced their name.

In their own words: Asian Americans’ experiences with having their name mispronounced

While having one’s name mispronounced is not always perceived as an incident of discrimination, names are strong indicators of other aspects of identity, such as ethnic origin, religion, gender and more. Having one’s name mispronounced can also have profound institutional and interpersonal impacts.

In our 2021 focus groups of Asian Americans, some participants talked about the experience of having their name routinely mispronounced. Additionally, many shared that they went by multiple names: their given name, which often reflected their origin or culture, and a second “easier to pronounce” Anglicized or American name.

“When you walk on the street, someone speaks to you like [in Korean or Japanese]. I am not Korean or Japanese, and this discrimination act is speaking this way when seeing Asian people. Another example [is that] average Americans actually can hardly read out my name. One day I went to see a dentist. He asked me how to read my name. After I told him, he said, ‘Are you sure you know how to read your name?’ He thought it was funny, but it was actually an offensive question, a kind of microaggression. There are many cases where others sort of praise you, but in fact it is indirect disrespect for your race.”

–Immigrant woman of Chinese origin in early 30s (translated from Mandarin)

“Nobody ever seems to be able to get my name right. And what is the number one thing that is your identity? It’s your name. So, the fact that nobody – even if I explain how to say it – people can’t say it. I have a list of over 200 names that I’ve been called, so it’s insane. Also, you go to a store and they have the names on magnets and keychains and your name is never, ever, ever going to be there. And as a kid I would always look and my mom would be like, ‘You know your name’s not going to be there, so what are you doing?’ And I’m like, ‘Yeah but I like to, you know, just look anyway.’ … Versus like you go to India and [my name is very common] so you see it on the street.”

–U.S.-born woman of Indian origin in late 20s

“Being Lao, my name is very strange [to Americans]. People don’t know what I am or what gender I am, like I share the same name with a bunch of different girls at my schools. But when they see my name, they’re not sure if it’s like Muslim, African, or whatever, and I feel like that hurts my job experiences. Even my friends tell me, ‘That’s your name? You don’t have like a normal name?’ They don’t know what to expect. They don’t know me [so they say things] like, ‘You speak good English,’ or whatever, stuff like that.”

–U.S.-born man of Laotian and Chinese origin in mid-20s

Discrimination experiences of being treated as foreigners

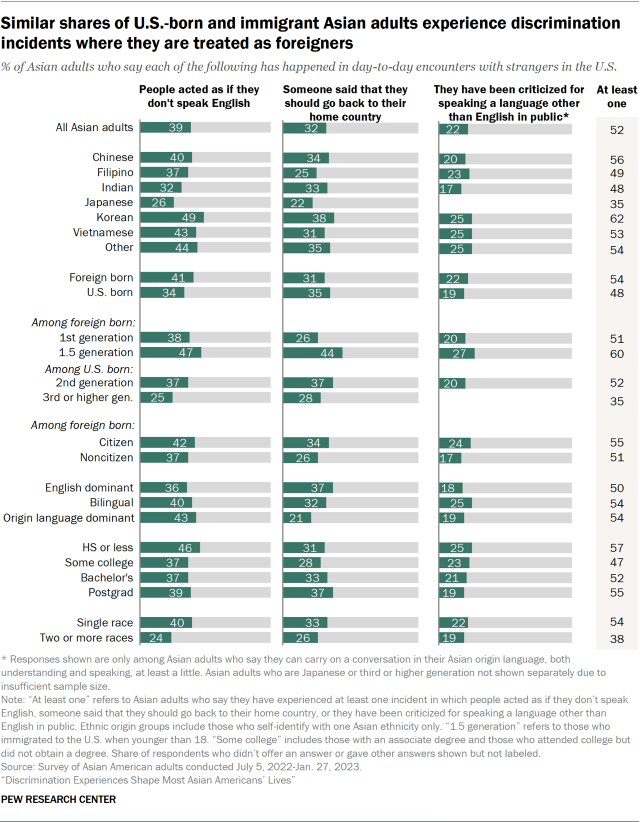

In their daily lives, 52% of Asian Americans say they have experienced at least one of three discrimination incidents in which a stranger treated them like a foreigner.

Whether Asian adults have had these experiences varies across some Asian ethnic origin groups:

- 49% of Korean Americans say strangers have acted as if they didn’t speak English in day-to-day encounters, compared with smaller shares of Chinese (40%), Filipino (37%), Indian (32%) and Japanese (26%) adults.

- About three-in-ten or more Korean, Chinese, Indian and Vietnamese adults and those who belong to less populous origin groups (those categorized as “other” in this report) say someone has told them to go back to their “home country.” About one-quarter of Filipino and Japanese adults say the same.

Regardless of nativity, similar shares of U.S.-born Asian adults (48%) and immigrants (54%) have experienced at least one of these three incidents.

Experiences, however, vary by immigration generation to some extent:

Qualitative research findings on how Asians are often seen by others as foreigners

An August 2022 report explored Asian Americans’ experiences with the “forever foreigner” stereotype. Here are some key findings related to the survey:

- Many Asian Americans shared a common experience of being asked where they are “really from,” implying that strangers see them as foreigners or that they do not fit their idea of what an “American” is supposed to look like.

- Whether participants were immigrants or U.S. born, many said they experienced this even if they or their families have lived in the country for decades or generations. Speaking fluent English also does not prevent others from asking them this question.

- Some U.S.-born participants said they avoided talking about their ethnic origin because it often led to misunderstandings and assumptions that they are immigrants.

- Japanese American participants shared their stories of being incarcerated with their families during World War II and being forced to leave their homes behind.

- Among immigrants, those who came to the U.S. as children (1.5 generation) are more likely than those who came as adults (first generation) to say someone has told them to go back to their “home country” (44% vs. 26%). And among the U.S.-born children of immigrant parents (second generation), 37% say they have had this experience.

- A higher share of 1.5-generation immigrants say strangers have acted as if they didn’t speak English than first-generation immigrants (47% vs. 38%).

Among immigrants, naturalized U.S. citizens are more likely than noncitizens to say they have encountered some of these incidents:

- 34% of naturalized citizens say someone has told them they should go back to their “home country,” compared with 26% of noncitizens.

- Among those who can speak the language of their Asian origin country, 24% of citizens say they have been criticized for speaking a non-English language in public, higher than the share of noncitizens who say the same (17%).

Asian Americans’ experiences with being treated like a foreigner by strangers vary by education:

- 46% of Asian adults with a high school degree or less say strangers have acted as if they didn’t speak English, higher than the shares among those with at least some college experience.

- On the other hand, Asian adults with higher levels of education are more likely to say that a stranger has told them to go back to their “home country.” About one-third of those with a bachelor’s degree or more say they have had this experience, compared with smaller shares of those with some college experience or less.

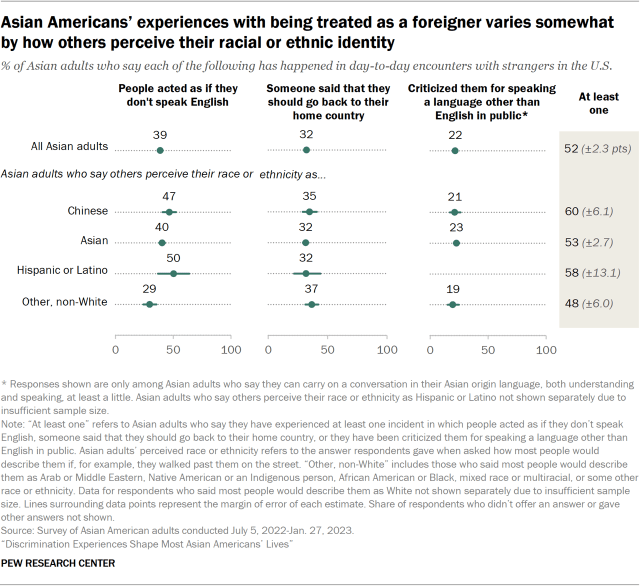

Asian Americans’ perceived racial or ethnic identity is also associated with whether they are treated as foreigners in day-to-day encounters:

- Asian adults who are perceived as Chinese, Asian, or Hispanic or Latino are more likely than those who are perceived as some other non-White race or ethnicity to say strangers have acted like they didn’t speak English.17

In their own words: How Asian Americans would react if their friend was told to ‘go back to their home country’

In the 2021 qualitative study of Asian Americans, we asked participants what they would do if someone told a close friend who just immigrated to the U.S., “Go back to your country, you don’t belong here!” We asked participants what they would say if their friend called them and asked, “Is this normal? What should I do?”

Participants answered with a variety of responses, including saying they would offer emotional support and offer strategies that could be summarized as “walk away,” “record and report” and “speak up.”

For those who suggest their friend walk away, some see it as rational and best for their friend’s safety.

“I personally have had a similar experience. This is a free country so you can’t stop other people from saying anything. … The main thing is to ensure your own personal safety.”

–Immigrant woman of Taiwanese origin in mid-20s (translated from Mandarin)

Participants also suggest their friend record the conversation if they can and report it to either an authority where the incident took place or the police.

“I also agree that whatever happens, we should calm down, and [if] I feel like I’m being attacked, I have to call the police for protection. That is my freedom. Other people can’t invade me, yell at me like that. But unfortunately it happens more often than I thought. I also have some friends or acquaintances who have been in the same situation.”

–Immigrant woman of Vietnamese origin in early 40s (translated from Vietnamese)

Immigrant participants are more likely to mention reporting the incident, while U.S.-born participants tend to express more doubt about whether police involvement would be helpful in the situation if there was no physical violence.

A number of participants would suggest their friend to speak up. Some see this as a chance to educate the aggressor:

“I’m a bit of a smartass and I would just tell them unless you’re [an] Indigenous [person], you should go back too. … [And] if you don’t like Chinese then you can’t have Chinese food. Things like that where they don’t realize that it’s already a part of their lives and kicking them out is going to take a piece of their own life with them.”

–U.S.-born man of Japanese origin in early 60s

“I would say, the answer would be that it is not your country either. It is a country of immigrants. … [I]t’s not you but your father or grandfather who came here. So, you too have to go to your country. Then it is everyone’s country.”

–Immigrant man of Bangladeshi origin in mid-50s (translated from Bengali)

Among U.S.-born participants who advocated for speaking up, some compared their response to how their parents might react:

“My parents would say, ‘Don’t say anything. Keep your eyes down and keep walking.’ … because they don’t know their rights and they don’t know the language, so they live in a different kind of fear of not being understood. But we growing up here know how to stand our ground.”

–U.S.-born man of Pakistani origin in early 30s

And while some Asian immigrants echo this sentiment, others elaborate on why they would encourage their children to speak up:

“If that happened to my child, the meaning is different from the situation when the same thing happened to me. They were born in this country and were supposed to be recognized as an American, but I think people say that to them because they look Asian. I would tell them that not everyone is like that, then they should protect themselves. If this happens, they can take [their] cellphone [to record the incident] and bring it to the police, or I would give them pepper spray for self-defense.”

–Immigrant woman of Japanese origin in mid-30s (translated from Japanese)

Many participants also said their suggestions to their friend in the scenario would ultimately depend on the situation.

“I guess if there is any kind of Asian association or something, that could help us in higher levels. That would help. But I don’t know. It’s hard because you can talk. You can tell that person back if that person’s not very bulky and acts like he’s going to hit you.”

–U.S.-born woman of Chinese origin in early 20s

“I would say ‘You can go home if you hate it.’ I don’t know what that person moved to the U.S. for, but if you have something you want to do, you should do it without being discouraged by such situations, so if you don’t like it, you can leave, and if you can do it, you can stay.”

–Immigrant man of Japanese origin in mid-20s (translated from Japanese)