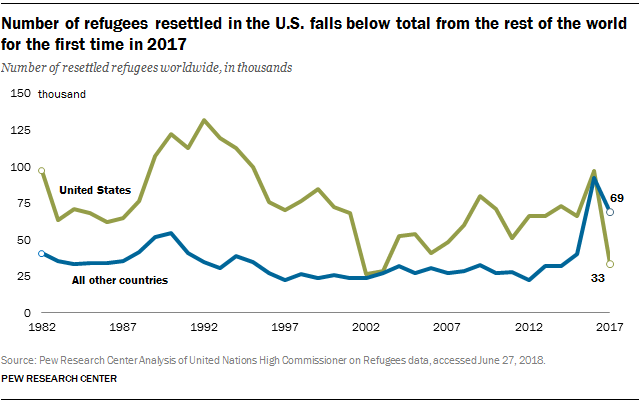

The number of refugees resettled in the United States decreased more than in any other country in 2017, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of new data from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). This represents the first time since the adoption of the 1980 U.S. Refugee Act that the U.S. resettled fewer refugees than the rest of the world.

The U.S. has historically led the world in refugee resettlement. Since 1980, the U.S. has taken in 3 million of the more than 4 million refugees resettled worldwide.

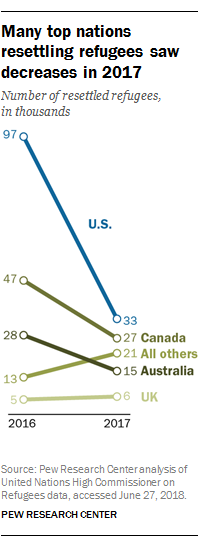

But in 2017, the U.S. resettled 33,000 refugees, the country’s lowest total since the years following the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks and a steep drop from 2016, when it resettled about 97,000.

Non-U.S. countries resettled more than twice as many refugees as the U.S. in 2017 – 69,000 – even though refugee resettlement in these nations was down from 92,000 in 2016.

Previously, the closest the rest of the world had come to surpassing the U.S. on this measure was 2003, when the U.S. resettled about 28,000 refugees and the rest of the world resettled about 27,000.

Despite a sharp single-year decline in refugee resettlement, the U.S. still resettled more refugees (33,000) than any other one country. Following the U.S. were Canada (27,000), Australia (15,000) and the United Kingdom (6,000). Sweden, Germany, Norway and France each resettled about 3,000 refugees. Per capita, Canada led the world by resettling 725 refugees per 1 million residents, followed by Australia (618) and Norway (528). The U.S. resettled 102 refugees per 1 million U.S. residents.

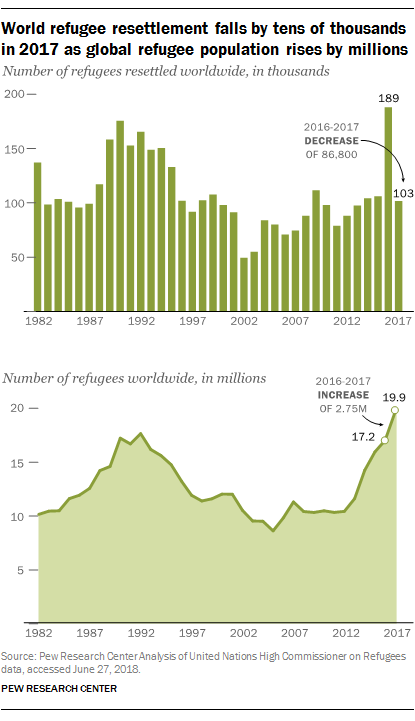

Overall, the world resettled 103,000 refugees in 2017, down from 189,000 in 2016. The broad-based decline included decreases in other leading countries in refugee resettlement, such as Canada and Australia, though the drops in these countries were more modest than those in the U.S.

Refugee resettlement involves a different group of migrants than those seeking asylum by entering Europe via the Mediterranean, coming to Canada via the U.S. and crossing into the U.S. at its southern border. Asylum seekers migrate and cross a border without having received prior legal permission to enter their destination country, and then apply for asylum. Resettled refugees, by contrast, don’t enter their destination country until they have legal permission to do so, because they apply for refugee status while in another country. The refugee approval process can take several months or years while destination countries complete security checks on prospective refugees.

The decline in refugee resettlement comes as the global refugee population increased by 2.75 million, and reached a record 19.9 million in 2017, according to UNHCR. This exceeds the high in 1990, following the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Refugees represent nearly a third (30%) of the world’s displaced population – people forced to leave their homes due to persecution, conflict, violence or human rights violations. The number of internally displaced people – those displaced within their home country – reached about 40 million in 2017, bringing the world’s total displaced population to 68.5 million in 2017 (a total that also includes Palestinian refugees and asylum seekers).

More than half (56%) of refugees resettled worldwide were citizens of countries in the Middle East-North Africa region, mostly from Syria. Another 23% were from sub-Saharan African countries, while 15% came from Asian countries.

U.S. refugee resettlement is on pace to remain at historically low levels in 2018. The Trump administration lowered the refugee ceiling for fiscal 2018 to 45,000 refugees – the lowest cap since the Refugee Act was adopted by Congress. The U.S. has admitted more than 16,000 refugees with about three months remaining in the current fiscal year, according to U.S. State Department data. The number of Muslim refugees admitted to the U.S. has dropped more than other religious groups. (Global refugee resettlement data for 2018 are unavailable.)

Correction (July 5, 2018): In a previous version of this post, the scale used in per-capita resettlement figures for Canada, Australia, Norway and the United States was incorrect. The numeral figures given (725, 618, 528 and 102, respectively) should have been per 1 million residents, not per 100,000.