The issue of paid family and medical leave has captured the attention of policymakers and advocates on both sides of the political aisle, as a growing share of working parents and an aging population put mounting pressure on American workers to balance family caregiving responsibilities and work obligations. A new Pew Research Center study finds that large shares of adults express support for paid family and medical leave, and most supporters say employers should cover the costs. Still, about half of Americans say the federal government should require employers to provide this benefit.

These findings are based on two new surveys of randomly selected U.S. adults conducted by Pew Research Center with support from Pivotal Ventures: one of adults in general, and the other of those ages 18 to 70 who were employed for pay and have taken – or who needed or wanted but were unable to take – parental, family or medical leave in the past two years.

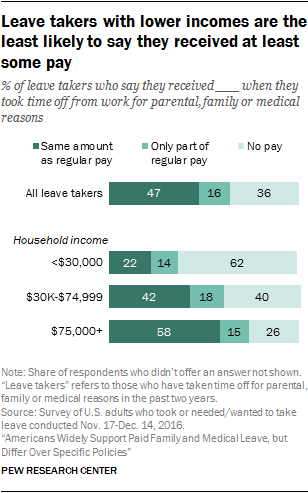

The study also finds that the experiences of Americans who have taken family or medical leave in recent years – including the amount of time they took off, whether they received pay, and how they coped with the loss of wages and salary if they didn’t receive full pay during their leave – vary sharply by income.

Here are six key takeaways from the report:

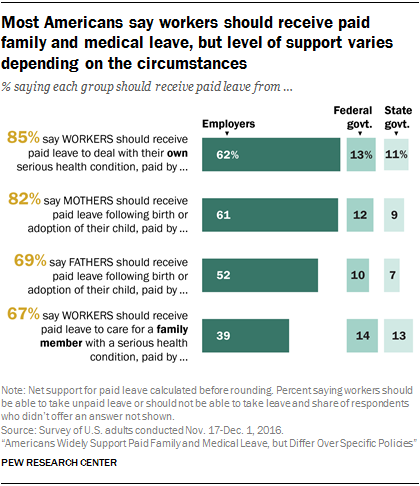

Support for paid family and medical leave is widespread, but it is greater under some circumstances than others. About eight-in-ten Americans (82%) support paid leave for mothers following the birth or adoption of a child, while 69% support paid paternity leave for fathers. And while 85% support paid leave for workers dealing with their own serious health condition, fewer (67%) support paid leave for those caring for a family member who is seriously ill.

More Americans say that employers, rather than the federal or state government, should be responsible for providing pay for workers who take leave. For example, roughly six-in-ten adults say employers should provide pay for workers who need to deal with their own serious health condition (62%) and for mothers following birth or adoption (61%).

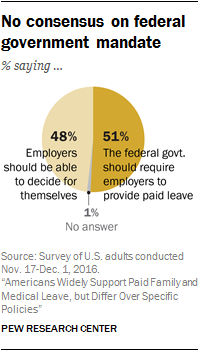

There is no consensus on whether there should be a federal government mandate for paid family and medical leave or on the best policy approach for dealing with paid leave. About half of Americans (51%) say the federal government should require employers to provide paid leave, while a similar share (48%) says that employers should be able to decide for themselves.

When it comes to specific policies for the government to deal with employees who need to take time off from work for family or medical reasons, the public has more positive views of policies that incentivize employers versus those that establish a government fund. Roughly four-in-ten or more Americans say they strongly favor providing tax credits to employers that provide paid leave (45%) or allowing workers to set aside monthly pretax contributions into a personal account that can be withdrawn when they need to take leave (39%). About three-in-ten (28%) strongly favor providing paid leave through new or higher taxes on the wealthy or corporations, and about a quarter (24%) strongly support the establishment of a government fund for employers and employees to pay into through payroll contributions that would then provide paid leave to workers who needed it.

The need for family and medical leave – whether paid or unpaid – is felt broadly across the U.S. Roughly six-in-ten Americans (62%) say they have taken or are very likely to take time off from work for family or medical reasons at some point. Among adults who were employed in the past two years, 27% say they have taken parental, family or medical leave during this period. In addition, 16% of those who were employed in the past two years say they needed or wanted to take these types of leave during this period but were unable to do so.

Blacks and Hispanics, those without a bachelor’s degree and those with annual household incomes under $30,000 are more likely than whites and those with more education or higher incomes to say they weren’t able to take leave when they needed or wanted to.

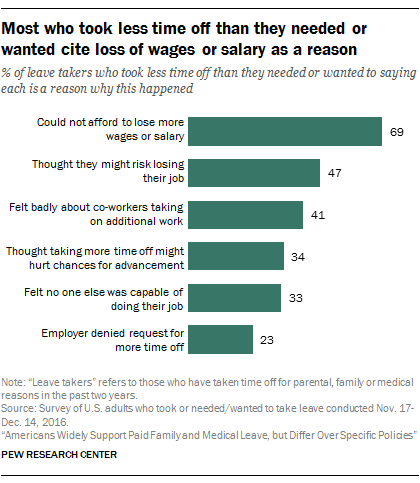

Many leave takers – including 56% of those who took parental leave – say they took less time off than they needed or wanted to. Financial concerns top the list of reasons why some leave takers returned to work more quickly than they would have liked to or didn’t take time off at all. About seven-in-ten leave takers (69%) who took less time off than they needed or wanted to say they couldn’t afford to lose more wages or salary. About half (47%) say they thought they might lose their job – a concern more widely felt among lower-income workers.

Leave takers with lower incomes are far less likely than those with higher incomes to receive pay when they take time off from work for family or medical reasons. Among all who took family or medical leave in the past two years, 47% say they received their regular pay, while 16% say they received only partial pay and 36% say they received no pay. But among leave takers with annual household incomes under $30,000, 62% say they received no pay, compared with 26% of those with household incomes of at least $75,000.

Among leave takers who received at least some pay, most (79%) say that at least part of that pay came from vacation days, sick leave or paid time off that they had earned. And roughly one-in-five say they used temporary or short-term disability insurance provided by their employer (22%) or family or medical leave benefits paid by the employer (20%) for at least part of their pay.

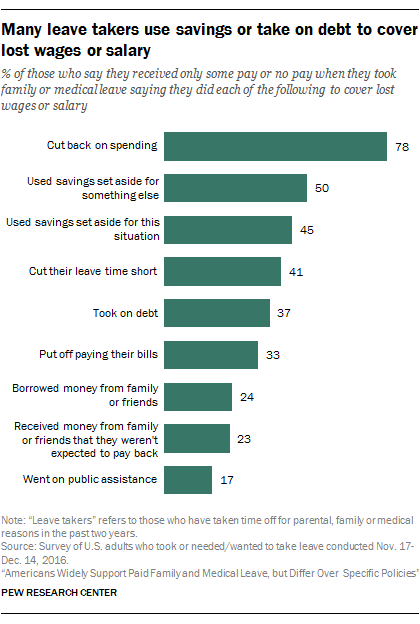

To cover lost wages, many leave takers take on debt or use savings. About eight-in-ten leave takers (78%) who took unpaid or partially paid family or medical leave say they cut back on their spending to compensate for lost wages or salary. Substantial shares also say they used savings set aside for something else (50%), used savings set aside for the reason they took leave (45%), cut their leave short (41%) or took on debt (37%). A third say they put off paying bills and about a quarter say they borrowed money from family or friends (24%) or received money they weren’t expected to pay back (23%). Nearly one-in-five (17%) say they went on public assistance to cover the lost wages or salary.

Leave takers with household incomes under $30,000 are far more likely than those with higher incomes to say they had to take more consequential measures to compensate for lost wages, such as taking on debt, putting off paying bills and going on public assistance when they don’t receive full pay for their leave – and this is particularly the case among those who have taken parental leave. To deal with the loss of wages or salary, about six-in-ten (57%) parental-leave takers with household incomes under $30,000 who didn’t receive full pay during their leave say they took on debt and 48% say they went on public assistance. By comparison, 36% of parental-leave takers with household incomes of at least $75,000 who didn’t receive full pay during their leave say they took on debt and just 5% say they went on public assistance.

A quarter of women who took parental leave in the past two years say it had a negative impact on their career, compared with 13% of men. By contrast, 66% of men who took paternity leave and 54% of women who took maternity leave say it didn’t make much of a difference for their job or career.

The median length of maternity leave far exceeds that of paternity leave (11 weeks vs. one week, respectively). But women with lower household incomes generally took shorter maternity leaves than women with higher incomes. For mothers with household incomes under $30,000, the median length of leave was six weeks, compared with 10 weeks for those with household incomes between $30,000 and $74,999 and 12 weeks for mothers with household incomes of $75,000 or more.