Reports of racist and xenophobic slurs against players and fans have continued to emerge during the World Cup. Two fans were arrested last weekend after chanting racist remarks during the match featuring Argentina vs. Bosnia-Herzegovina.

In an attempt to combat hate speech during the tournament, FIFA and Brazilian authorities initiated an anti-racism campaign using the hashtag #SayNoToRacism. Hate speech is taken seriously in Brazil, where racist or religiously intolerant speech or actions are prohibited by law and carry penalties including imprisonment.

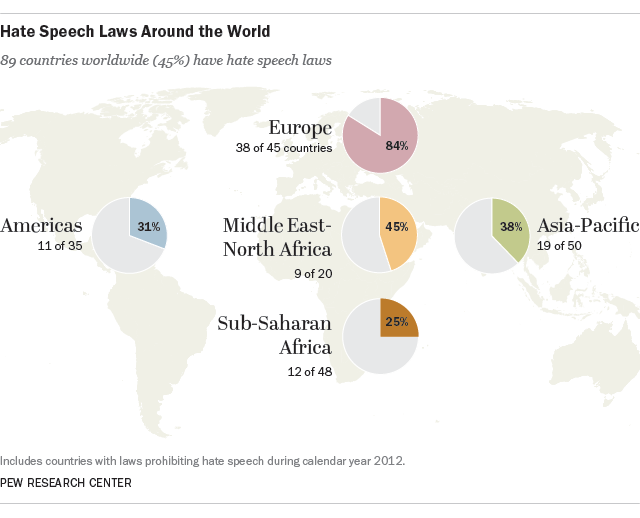

Brazil is not the only country with a law that penalizes hate speech. A new Pew Research analysis finds hate speech laws in 89 countries around the world (45%), according to 2012 data. In some countries, the laws protect only certain religious or social groups, while others have broader laws, covering words or actions that insult, denigrate or intimidate a person or group based on race, gender, religion, ethnicity or other traits.

Although these laws are on the books, in some countries they are not enforced. However, in countries where penalties are imposed for hate speech, they often include fines or short-term jail sentences. A spectator in Spain was arrested earlier this year on suspicion of throwing a banana at a Brazilian player, and in 2012, a man in the United Kingdom received a jail sentence for posting racist and offensive comments on Twitter after a player collapsed on the field.

Laws against hate speech are most common in Europe, where 84% of countries (38 of 45) have such laws or policies (as of 2012). In 2008, the European Union passed a framework decision to combat hate speech and other expressions of racism and xenophobia – although member states have yet to consistently enforce the decision. In France, inciting racial or ethnic hatred is illegal, and noncitizens may be deported for such actions.

Some European countries have hate speech laws in place that include policies specifically targeting soccer and other sporting events. In the United Kingdom, for instance, the Football Offences Act (initially passed in 1991) prohibits racist chanting at football matches. In Spain, it is illegal to incite hatred because of race, religion, ethnicity, gender, nationality or sexual orientation, and athletic teams and stadiums can face sanctions for “actions that disparage religion if committed by professional athletic clubs, players or fans during sporting events,” according to the U.S. State Department.

Similar measures are in effect in nine of the 20 countries in the Middle East-North Africa region (45%) and more than a third of the countries in the Asia-Pacific region (38%, or 19 of 50). In Indonesia, for example, it is illegal to incite hatred toward individuals or community groups because of race, religion or ethnicity.

Hate speech laws were present in a quarter of countries in sub-Saharan Africa as of 2012 (12 of the 48 countries) and about three-in-ten countries in the Americas (31%, 11 of 35).

In the United States, courts have traditionally struck down attempts to limit hate speech. Most recently, during a 2011 case involving one of the Westboro Baptist Church’s anti-gay protests at a military funeral (Snyder v. Phelps), the U.S. Supreme Court reaffirmed the First Amendment’s protection of free speech. Athletes occasionally encounter racist comments in the United States, often on Twitter.

This analysis is based on our ongoing research on global restrictions on religion. For more on our sources and procedures, see our most recent report on the topic.