A greater share of mothers are not working outside the home than at any time in the past two decades, according to a new Pew Research Center report. After declining for several decades — bottoming out at 23% around the turn of the century — the share of stay-at-home mothers has risen in fits and starts over the past decade and a half, to 29% in 2012, according to the Pew Research analysis of census data.

[e]

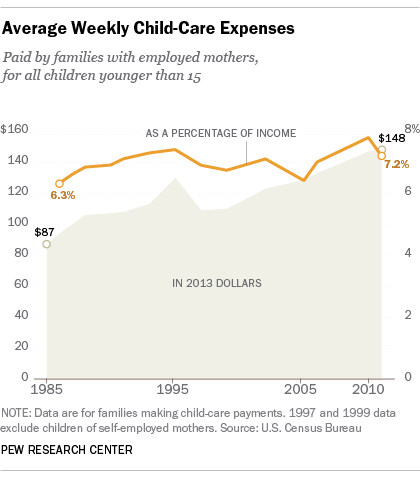

Mothers who do work are paying more than ever for child care. In inflation-adjusted dollars, average weekly child care expenses for families with working mothers who paid for child care (24% of all such families) rose more than 70% from 1985 ($87) to 2011 ($148), according to research by the Census Bureau. For those families, child-care expenses represent 7.2% of family income, compared to 6.3% in 1986 (the earliest year available).

But child care costs hit families at different income levels very differently, according to the census data. In 2011, for instance, families with employed mothers whose monthly income was $4,500 or more paid an average of $163 a week for child care, representing 6.7% of their family income. Families with monthly incomes of less than $1,500 paid much less –$97 a week on average — but that represented 39.6% of their family income.

Those figures are national averages, of course — the actual cost of child care depends on such factors as the age of the child(ren), the type of facility, and where the family lives. According to the census data, for example, families whose youngest child was younger than 5 paid an average of $179 a week; those whose youngest was between 5 and 14 paid just $93 (reflecting that school-age children need fewer hours of care).

Overall in 2011, more than 2.7 million preschoolers with employed mothers (25.2% of preschoolers in that category) had their primary care arrangement through a day-care center, preschool or other organized facility, according to Census. The most common primary care arrangement was with parents or other relatives (48.6%); 12.9% of preschoolers with employed mothers were cared for primarily by non-relatives, either in their own home or the provider’s; the rest had some other arrangement or were in no regular one.

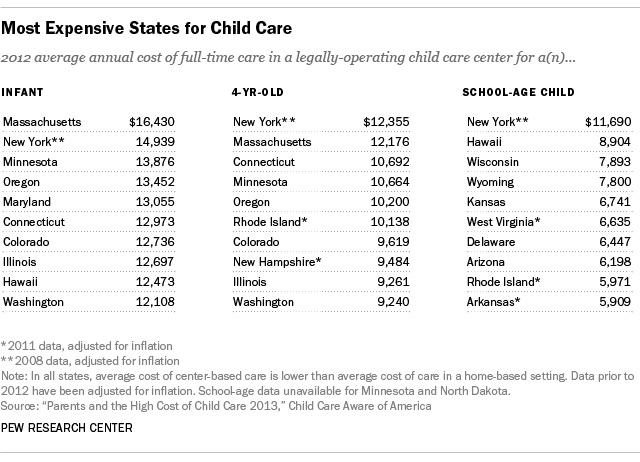

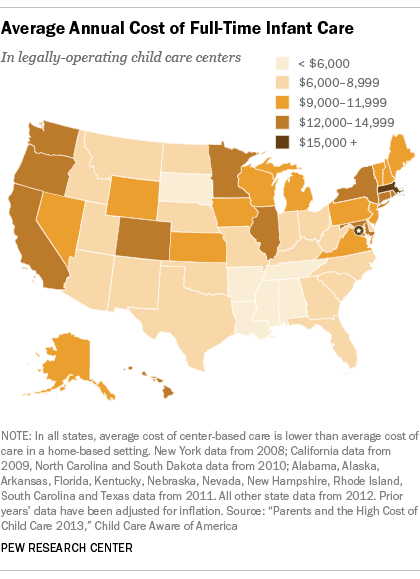

Costs vary considerably by geography. To get a sense of just how much variance there is, Child Care Aware of America, a national organization of local child care resource and referral agencies, surveyed its members last year on the average prices of care for infants, 4-year-olds and school-age children among child-care facilities and home-based caregivers in their states. New York and Massachusetts were the most expensive states in nearly every category, while the lowest costs typically were found in the South. (Washington, D.C., which topped all the lists, was excluded because it isn’t directly comparable to states.)