Supporters of a U.S.-led military strike against Syria have largely framed the issue as a matter of protecting global security by enforcing international law. Speaking Friday at the G-20 summit in Russia, President Obama stressed that the international norm against using chemical weapons must be maintained if that and other norms are to have any meaning.

But proponents of taking military action also have sought to cast the move as a moral imperative. “This is not the time to be spectators to a slaughter,” Secretary of State John Kerry told the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on Tuesday. “Neither our country nor our conscience can afford the cost of silence.” In his comments on Friday, Obama implicitly compared the debate over Syria to international inaction during the Rwandan genocide.

While the data from different surveys taken at different times varies, Americans generally are less willing to support foreign policies on moral or humanitarian grounds than when they are cast as directly benefiting the United States or its allies.

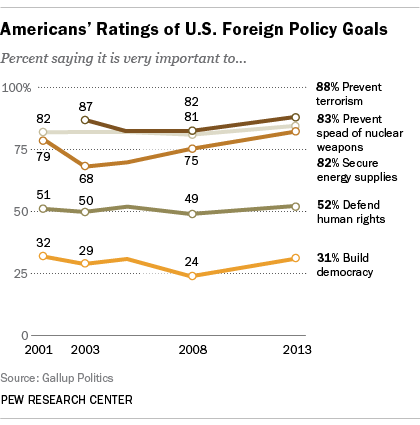

In February, when Gallup asked Americans how important various foreign-policy goals should be, 52% rated promoting and defending human rights in other countries as “very important.” Out of nine goals Gallup asked about, it ranked third from the bottom, ahead of “helping other countries build democracies” and “promoting economic development in other countries” (31% each). By far the strongest support — above 80% in each case — was given to goals related to U.S. national security and securing adequate energy supplies for the country.

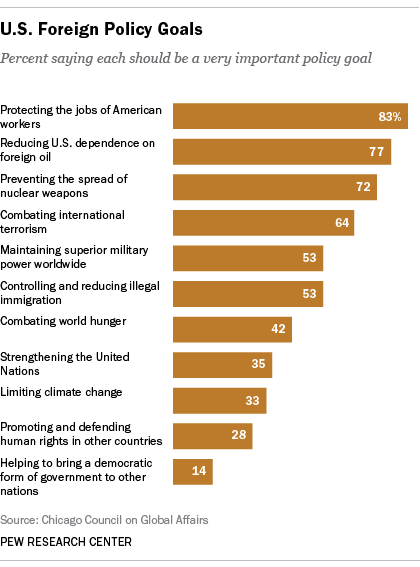

A similar 2012 survey by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs found considerably less support than Gallup for moral or humanitarian foreign-policy goals. Of 11 possible goals CCGA asked about, the two lowest-scoring ones were “promoting and defending human rights in other countries” and “helping to bring a democratic form of government to other nations,” with 28% and 14%, respectively, calling those very important. The top-rated goals in that survey? Protecting the jobs of American workers (83% saying that was very important) and reducing U.S. dependence on foreign oil (77%).

More generally, in a 2008 poll 35% of Americans “strongly” agreed that the United States “has a moral obligation to take a leadership role in world affairs,” with another 25% “somewhat” agreeing.

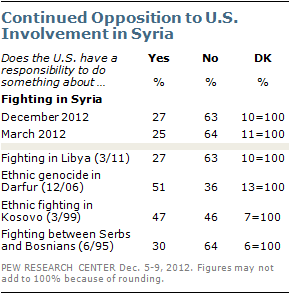

In June, before the Syrian government’s reported use of chemical weapons, Americans in a Pew Research poll were almost equally divided on whether the country had “a moral obligation to do what it can to stop the violence in Syria.” Fully 49% agreed and 46% disagreed — though that was an increase from the 27% who said in December 2012 that the United States had such a responsibility. (However, when we asked again last week, as it became clear that President Obama had decided on airstrikes, Americans said they opposed such action 48% to 29%, with 23% undecided.)

A question in March 2011 about Libya found about as little sense of U.S. responsibility, though higher percentages said the U.S. had a responsibility to do something about the fighting in Darfur in 2006 (51%) and fighting between Serbs and Bosnians in Kosovo in 1999 (47%).