Typically, East Asia is considered to encompass China, Hong Kong, Japan, Macau, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea and Taiwan. In geopolitical terms, Vietnam is often categorized as part of Southeast Asia. But we surveyed Vietnam along with East Asia for several reasons, including its historic ties to China and Confucian traditions. Moreover, Buddhists in Vietnam practice the same strain of Buddhism (Mahayana) found across East Asia.

Throughout this report, the term “East Asia” refers to Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan.

When discussing trends throughout the broader “region,” we include Vietnam.

For legal and logistical reasons, we did not survey several other places that are generally considered part of East Asia. At present, China does not allow non-Chinese organizations to conduct surveys on the mainland, and public opinion surveys are not possible in North Korea. Conducting nationally representative surveys in Mongolia is difficult due to the nomadic lifestyle of a large part of its people. We did not survey Macau because its population is relatively small.

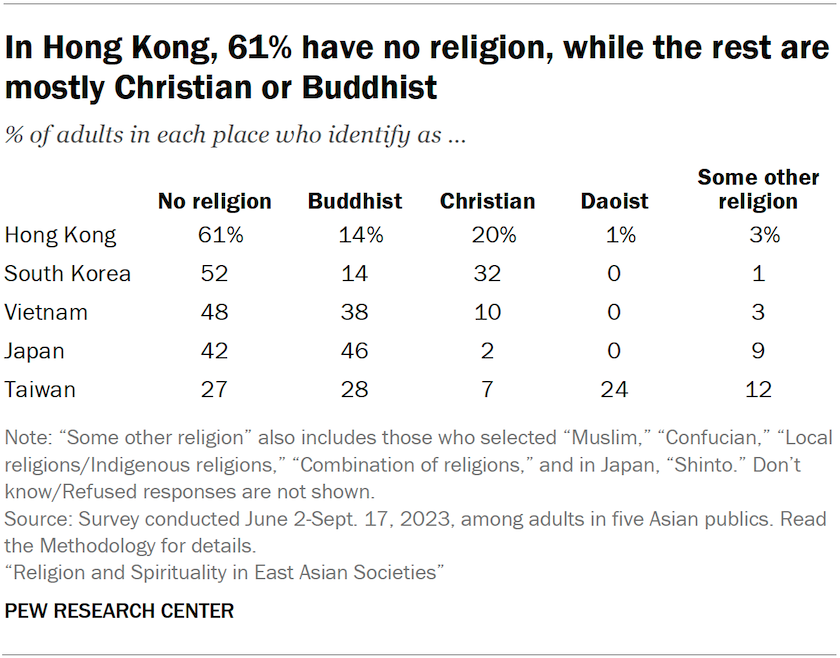

Most people in the five Asian societies surveyed either identify as Buddhist or say they have no religion. But substantial shares in South Korea and Hong Kong identify as Christian, and Taiwan has a sizable number of Daoists (also spelled Taoists).

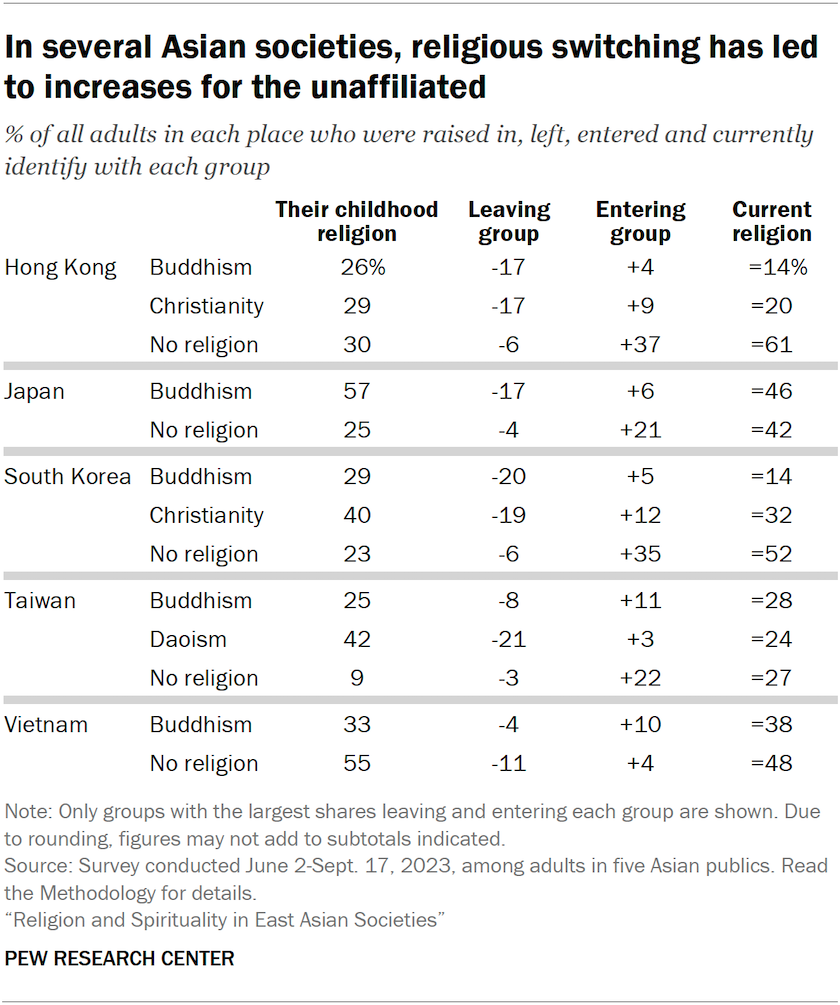

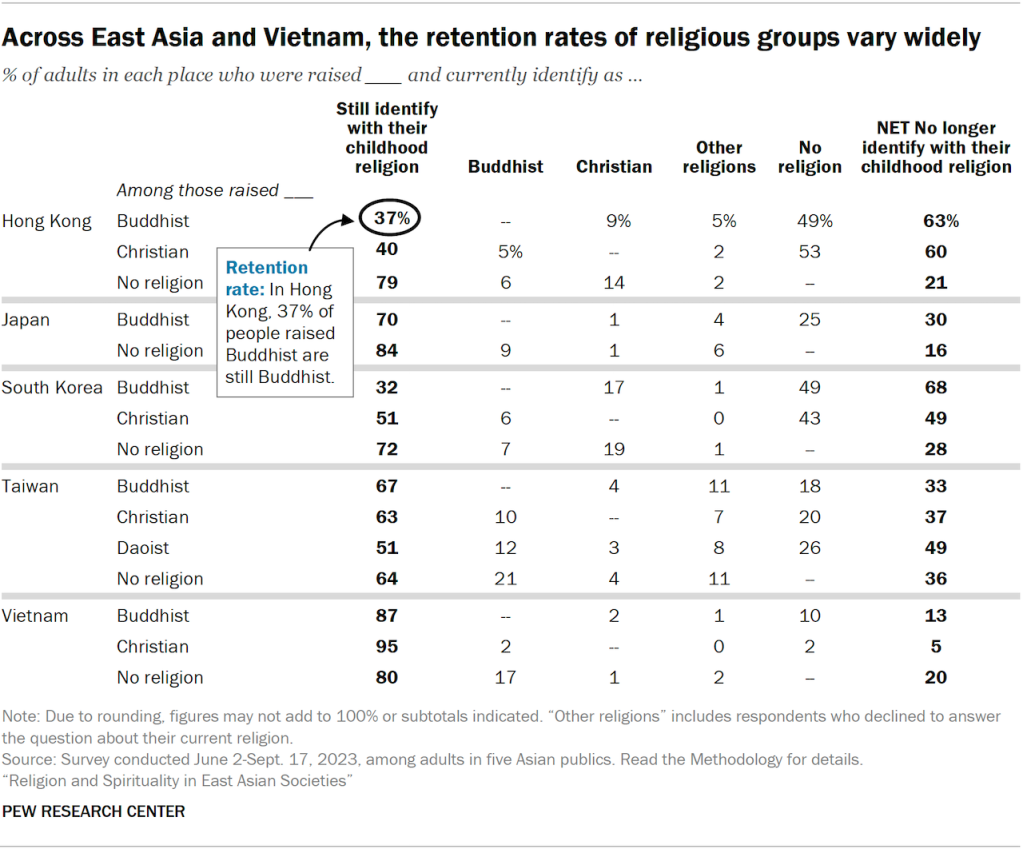

Religious “switching” – changing from one’s childhood religion to a different religious identity in adulthood – is quite common in Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan. Switching is less common in Vietnam.

People who were raised in a religion but no longer identify with any religion account for most of the switching in the region.

For example, in Hong Kong and South Korea, roughly half of adults say they have left the religion in which they were raised; many have given up Buddhism or Christianity and are now religiously unaffiliated.

In all five places, however, most people who say they were raised with “no religion” have retained that identity, remaining unaffiliated in adulthood.

Despite this region’s relatively high levels of religious switching, public attitudes toward proselytizing are mixed. Large majorities in Japan and South Korea say it is generally unacceptable for people to try to persuade others to join their religion. In Hong Kong, Taiwan and Vietnam, respondents are more supportive of conversion efforts.

Religious composition

In three places surveyed, the religiously unaffiliated are the largest group: Most adults in Hong Kong (61%), and roughly half in South Korea (52%) and Vietnam (48%), say they have no religion.6 Substantial shares in Japan (42%) and Taiwan (27%) say the same.

Buddhists also are prevalent in the region. We find that 46% of Japanese, 38% of Vietnamese and 28% of Taiwanese adults identify as Buddhist, while 14% in both Hong Kong and South Korea are Buddhist.

Christians are not the largest religious group in any of the five places surveyed, although roughly one-third of South Koreans identify as Christian, as do 20% of Hong Kongers and 10% of Vietnamese adults.

Overall, the religiously unaffiliated, Buddhists and Christians account for roughly 90% of adults or more in four of the places surveyed. In Taiwan, those three religious groups make up 62% of adults, and an additional 24% are Daoist.

We did not ask respondents to say which of the three major strands of Buddhism they follow, though past research has shown that Mahayana Buddhism is prevalent in Japan, South Korea and Vietnam. Mahayana, which originated in China, teaches its followers to strive to become bodhisattvas, or “wisdom bodies,” who work toward enlightenment for themselves and all beings. The other major strands of Buddhism – Theravada and Vajrayana (also known as Tibetan Buddhism) – are more prevalent in places such as Thailand, Sri Lanka and Nepal.

Evangelical Christians

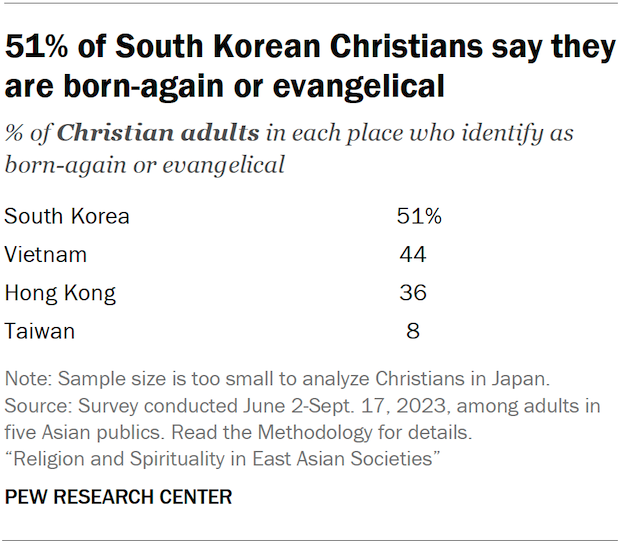

Adults who self-identify as Christian were asked a follow-up question: “Would you describe yourself as a born-again or evangelical Christian?”

About half of Christians in South Korea say they are born-again or evangelical. Smaller shares of Christians in Vietnam (44%) and Hong Kong (36%) give the same answer.

In South Korea, older Christian adults are more likely than those under 35 to say they are evangelical (54% vs. 38%). Christians without a college degree, as well as South Korean women, also are more likely than their counterparts to describe themselves as born-again or evangelical.

In Taiwan, only 8% of Christians describe themselves as born-again or evangelical.

Christians also were surveyed in Japan, but the number of Christians in our sample of Japanese adults is too small to allow their characteristics or views to be analyzed and reported separately.

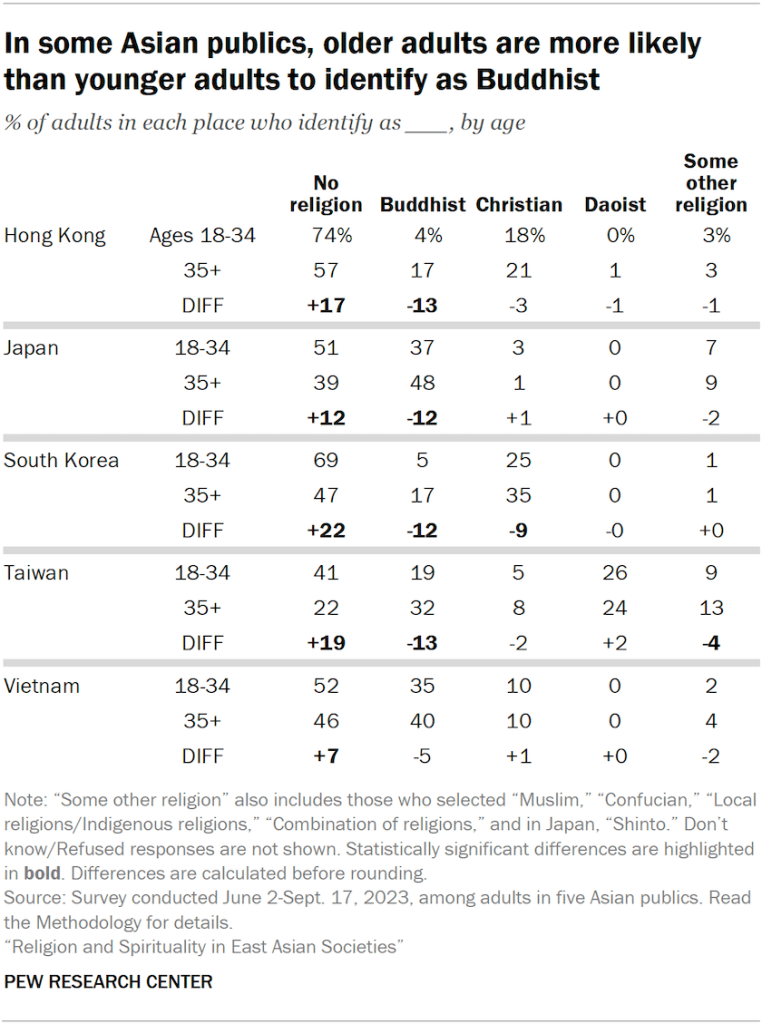

How religious identity differs by age

Younger adults (ages 18 to 34) are consistently more likely than older adults not to identify with any religion. In Taiwan, for instance, younger adults are almost twice as likely as older adults to be religiously unaffiliated (41% vs. 22%).

Younger adults also tend to be less likely than older adults to identify as Buddhist.

Among Christians, there are no wide age gaps except in South Korea, where 25% of younger adults and 35% of older ones identify as Christian.

Religious switching

When demographers study how a society’s religious mix is changing, they typically consider five factors that drive change over time: religious switching (the voluntary choices people make about which religious groups they belong to, if any); age structure (differences in the age and sex composition of groups); fertility rates (how many children are born to women in different religious groups); mortality rates (whether people in some religious groups live longer than others); and migration rates (how many people in each religious group are moving into and out of a particular place).

This report does not attempt to measure differences in fertility, mortality or migration between religious groups. However, we measured religious switching by asking respondents two separate questions:

- What is your religion, if any?

- Thinking about when you were a child, in what religion were you raised?

The responses to these two questions allow us to calculate what percentage of the public has left a religious group (or “switched out”) and what percentage has entered (or “switched in”).

Switching can go in multiple, and partially offsetting, directions. In Hong Kong, for example, 26% of adults say they were raised as Buddhists, but just 14% currently identify as Buddhist. This is because 17% of adults in Hong Kong were raised as Buddhists but now identify with some other religion (or with no religion), while 4% were not raised as Buddhists but have entered Buddhism as adults.

On balance, the survey finds that religious switching has resulted in an overall (or “net”) loss to Hong Kong’s Buddhist community of 12 percentage points, after rounding to the nearest integer.

Net gains and losses for each religious group

Across the region, the religiously unaffiliated population generally has experienced the biggest net gains from religious switching, drawing large shares from every other religious category in all places except Vietnam.

In South Korea, for example, 23% of adults surveyed say they were raised without a religion, but 52% currently identify as religiously unaffiliated – a gain of 29 points. This is because 35% of South Koreans have left their childhood religion to join the ranks of the unaffiliated, while just 6% who were raised unaffiliated have joined a religion.

Only in Vietnam is this pattern of net growth among the religiously unaffiliated reversed. There, the share who claim no religious identity has fallen 7 points between respondents’ childhoods and today (55% vs. 48%).

Meanwhile, Buddhism has experienced net losses in Hong Kong, Japan and South Korea. For instance, 57% of adults in Japan say they were raised Buddhist, while 46% are currently Buddhist – a net loss of 12 points (after rounding). This is because people who were raised Buddhist have left the community at a higher rate than people have entered Buddhism from other religious backgrounds. While 17% of Japanese adults were raised Buddhist but no longer identify as Buddhist, just 6% have switched into Buddhism after being raised in some other religious tradition.

In Taiwan and Vietnam, on the other hand, Buddhism has experienced slight net increases due to religious switching.

Also in Taiwan, Daoism has shrunk dramatically due to switching: 42% of adults say they were raised Daoist, compared with 24% who identify as Daoist today.

The percentages who identify as Christian have fallen over people’s lifetimes in Hong Kong (net loss of 9 points) and South Korea (down 8 points).

Retention rates or ‘stickiness’

Another way of measuring religious change is to look at retention rates: What percentage of all the people raised in a group remain in that group today? This is sometimes referred to as how “sticky” a group is.

Across the region, among survey respondents who say they were raised without a religion, most still do not identify with any religion today. Retention rates among the unaffiliated range from 64% in Taiwan to 84% in Japan.

Retention rates for Buddhists vary widely. Most people raised as Buddhists continue to identify with Buddhism in Vietnam (87%), Japan (70%) and Taiwan (67%). But far fewer have stuck with Buddhism in Hong Kong (37%) and South Korea (32%).

Meanwhile, Christians have relatively low retention rates in Hong Kong (40%) and South Korea (51%) but a higher rate in Taiwan (63%) and an exceptionally high rate in Vietnam (95%).

Across the region, most people who have left their childhood religion tend to be unaffiliated, no longer identifying with any religion. (Switching from having a religion to having no religion is often called disaffiliation. For figures on disaffiliation across Asia and other parts of the world, turn to the Overview of this report.) In Vietnam, for instance, 13% of people raised Buddhist have left Buddhism, and most of them (10% of all people raised Buddhist) now have no religion; 2% have become Christian and 1% identify with other religious groups.

Conversely, among those who were raised without a religion and have taken on a religion in adulthood, most have become either Buddhist (as in Vietnam) or Christian (as in South Korea.)

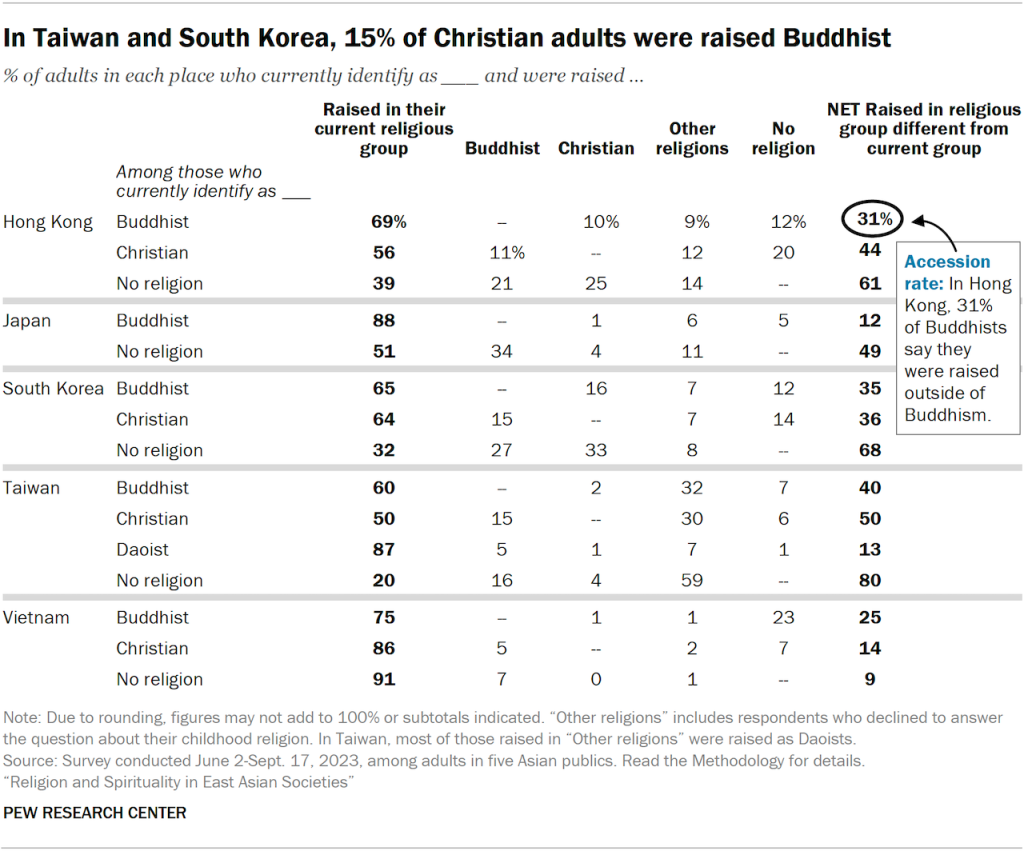

Which groups have the biggest shares of new entrants?

Yet another way of looking at religious change is to consider which religious groups have the largest percentages of new entrants, sometimes called an “accession rate.”

In general, the religiously unaffiliated are more likely than other groups to be composed of newcomers. For example, in Japan, 49% of the unaffiliated were raised in some religious community, while just 12% of Japanese Buddhists were raised outside Buddhism.

Once again, Vietnam bucks the trend. While 9% of Vietnam’s unaffiliated adults grew up with a religion, 25% of Vietnam’s current Buddhist adults were raised outside Buddhism. And most of these converts to Buddhism say they grew up unaffiliated.

Across the region, at least half of all Buddhists and Christians were raised in the religious community they identify with today.

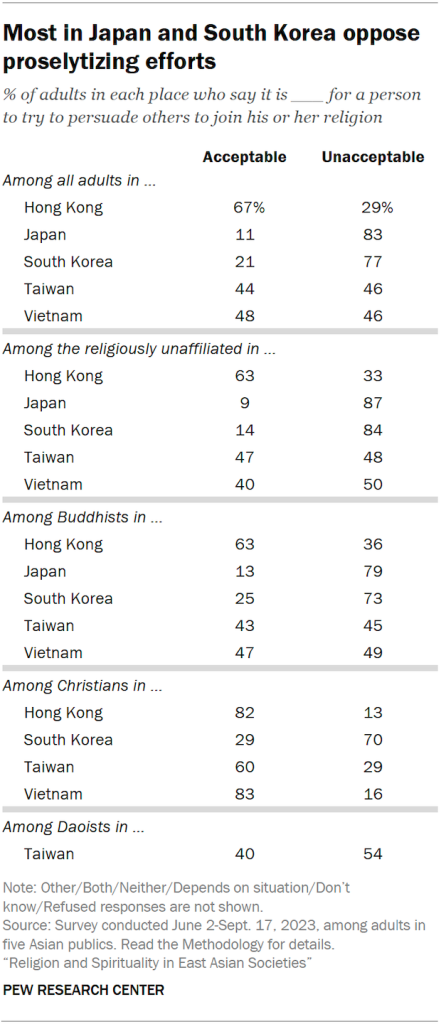

Persuading others to switch

People across East Asia and Vietnam express widely differing views on whether proselytizing (i.e., seeking religious conversions) is acceptable.

Most adults in Japan (83%) and South Korea (77%) say it is unacceptable for a person to try to persuade others to join his or her religion. This includes vast majorities of the religiously unaffiliated and Buddhists in both places. Most Christians in South Korea (70%) also oppose proselytization.

People in Taiwan and Vietnam are more divided about conversion efforts. In neither place do a majority say such efforts are acceptable or unacceptable.

Hong Kong is the only place surveyed where a majority of respondents say it is acceptable to proselytize (67%).

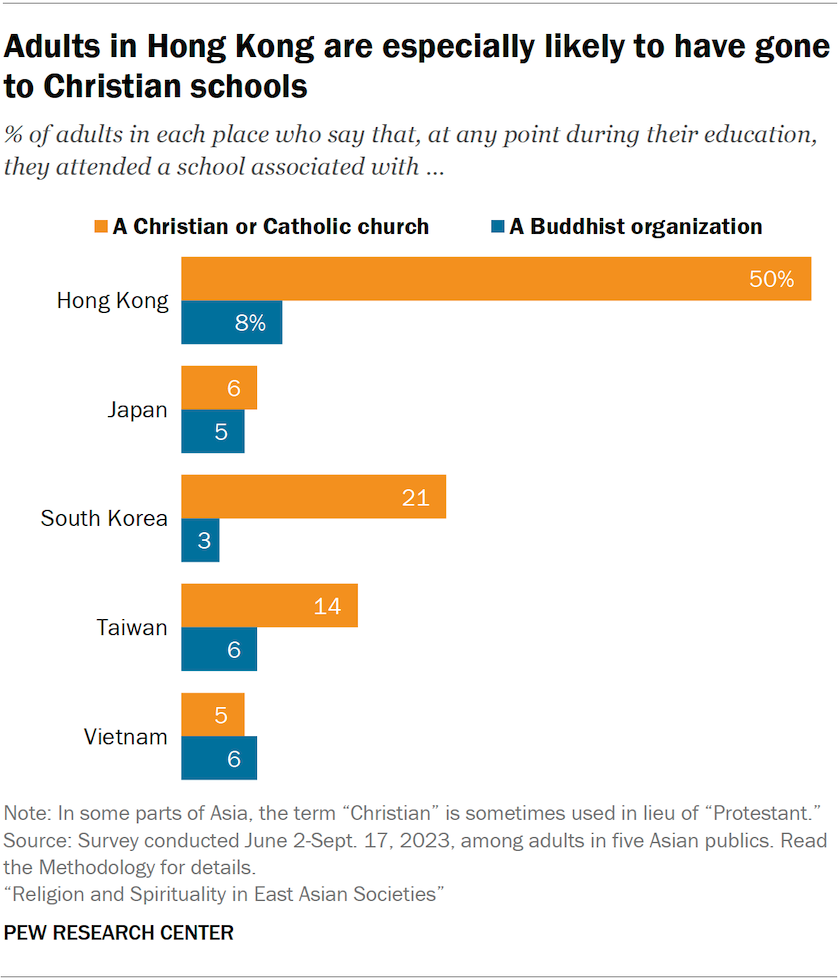

Attending Christian and Buddhist schools

Most adults throughout the region say they did not attend any school with a religious affiliation during the course of their education.

Hong Kong is an exception, with half of adults there saying they have attended a school associated with a Catholic or other Christian church. (This may be in part due to a large increase in church-run public education starting in the 1960s. Government statistics in 2022 showed that about half of primary school students in Hong Kong attended a school associated with a Catholic or other Christian church.)

In general, it’s more common for people in the places surveyed to have attended a school with Christian connections than one associated with a Buddhist organization.

In addition, Christians are more likely to have attended Christian schools than Buddhists are to have attended schools with Buddhist ties. For instance, 22% of Taiwanese Christians attended a school associated with a Christian or Catholic church, while 10% of Taiwanese Buddhists ever attended a school connected to a Buddhist organization.