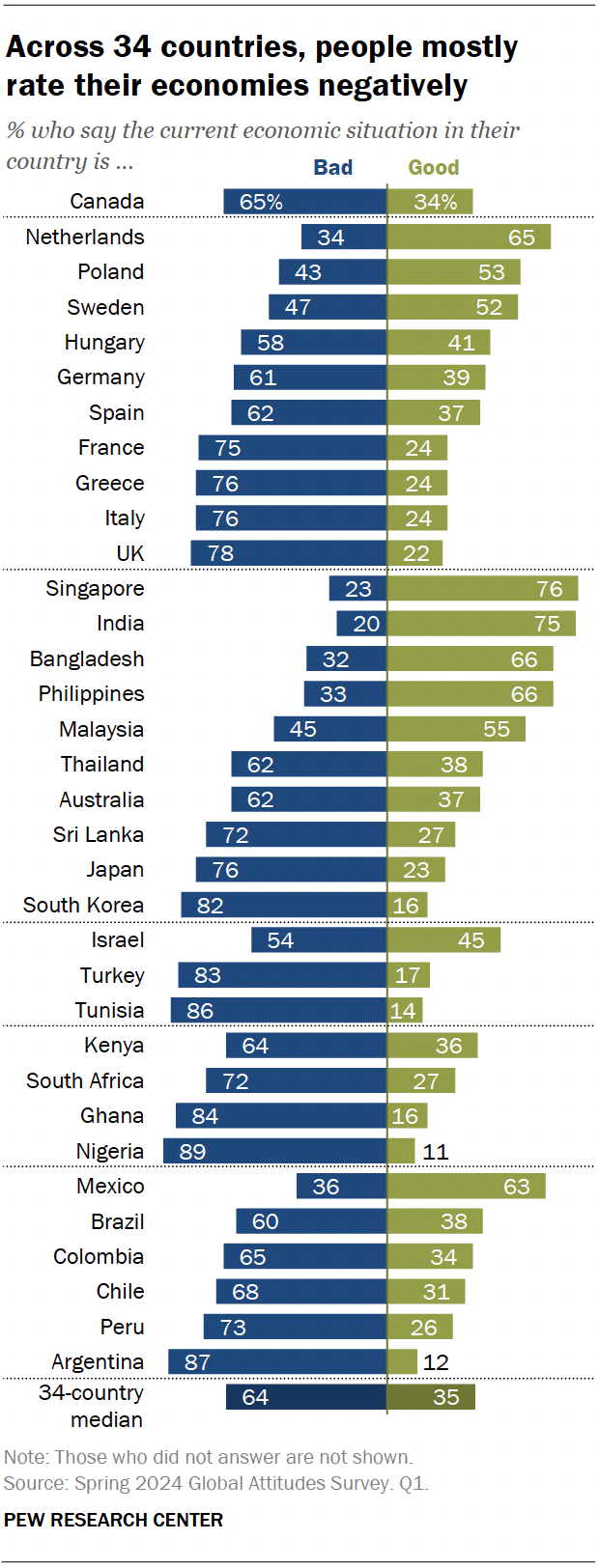

Economic ratings in 34 countries Pew Research Center surveyed this year are, on balance, more bad than good. A median of about two-thirds of adults (64%) rate their country’s economic situation poorly. The surveys were fielded amid stalled global trade and slow economic growth around the world.

This Pew Research Center analysis explores public opinion of the domestic economy in 34 countries in North America, Europe, the Asia-Pacific region, the Middle East, sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America.

This analysis draws on nationally representative surveys of 40,566 adults conducted from Jan. 5 to May 21, 2024. All surveys were conducted over the phone in Canada, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Japan, Malaysia, the Netherlands, Singapore, South Korea, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom. Surveys were conducted face-to-face in Argentina, Bangladesh, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ghana, Hungary, India, Israel, Kenya, Mexico, Nigeria, Peru, the Philippines, Poland, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Tunisia and Turkey. In Australia, we used a mixed-mode probability-based online panel.

To compare educational groups across countries, we standardize education levels based on the UN’s International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED).

To compare views of those who support the governing party or parties with those who do not, we grouped respondents based on their answers to a question asking them which political party, if any, they identified with in their country. For more, including country specific classifications, read our Political Categorization Appendix.

Prior to 2024, combined totals were based on rounded topline figures. For all reports beginning in 2024, totals will be based on unrounded topline figures, so combined totals might be different than in previous years. Refer to the 2024 topline to see our new rounding procedures applied to past years’ data.

Here are the questions used for the analysis, along with responses, and the survey methodology.

Evaluations are most negative in Argentina, Ghana, Nigeria, South Korea, Tunisia and Turkey. In each of these countries, more than eight-in-ten say their economy is bad, including more than four-in-ten who say it is very bad.

Adults in most European countries surveyed also offer negative evaluations of their economies, including three-quarters or more in France, Greece, Italy and the United Kingdom. Smaller majorities in Germany, Hungary and Spain agree.

Still, people in several countries have largely positive views of their economies. In Bangladesh, India, Malaysia, Mexico, the Netherlands, the Philippines and Singapore, majorities say their economy is good. About a third of Indian adults say the economic situation in their country is very good – the largest share of any country surveyed.

A separate Center survey from this spring shows that Americans are largely critical of their economy. Only 23% of U.S. adults say economic conditions are excellent or good. For more information, read “Public’s Positive Economic Ratings Slip; Inflation Still Widely Viewed as Major Problem.”

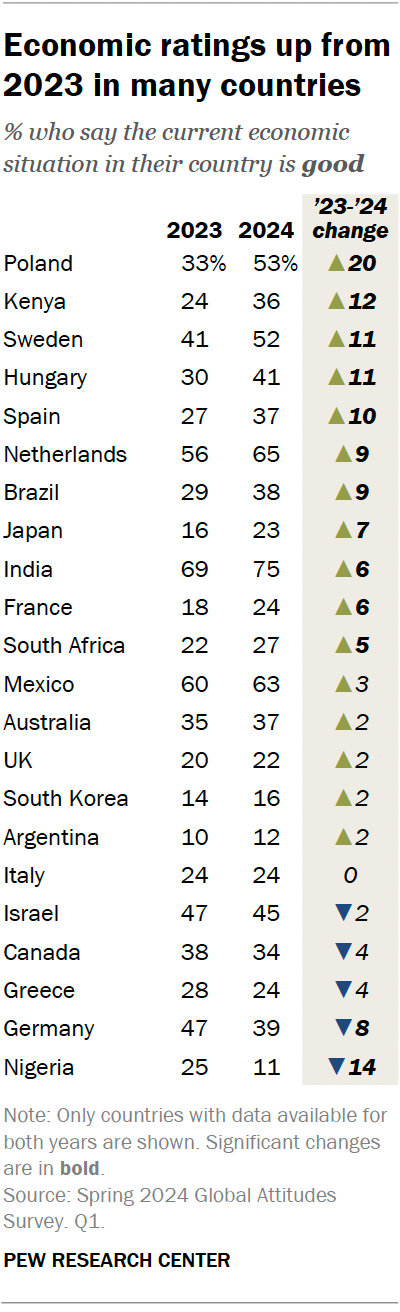

Change in economic ratings over time

Although economic ratings are negative in many places, they have improved since 2023 in 11 countries. For example, positive ratings jumped from 33% to 53% in Poland. This increase follows an October 2023 election where Poles voted to unseat the Law and Justice (PiS) party, which had ruled since 2015. The change in government prompted the European Union to release $149 billion in withheld funds to Poland during our survey period.

Significant single-year increases also occurred in Brazil, France, Hungary, India, Japan, Kenya, the Netherlands, South Africa, Spain and Sweden.

Nigeria and Germany are the only two countries surveyed in both years that saw notable decreases in positive economic ratings in the last year (by 14 and 8 percentage points, respectively). Nigerians, who have seen their economy slip from the largest in Africa in 2022 to the fourth largest this year, are coping with a near 30-year high inflation rate of 29.9%. And during the survey period in Germany, the country’s economy minister outlined especially low growth predictions for 2024 (0.2%), citing the impact of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

In a handful of countries, our most recent data prior to 2024 comes from 2019 or 2017, before the COVID-19 pandemic upended the global economy. In most of these places, ratings have dropped significantly since the last time we surveyed. For example, about four-in-ten Turkish adults (39%) called their country’s economic situation good in 2019; now just 17% give similarly positive ratings. Good ratings are also down 31 and 30 points from 2017 in Peru and Ghana, respectively.

Still, in those countries we did not find strong correlations between people’s ratings of their country’s economy and economic indicators such as gross domestic product, inflation and inequality (or how these changed).

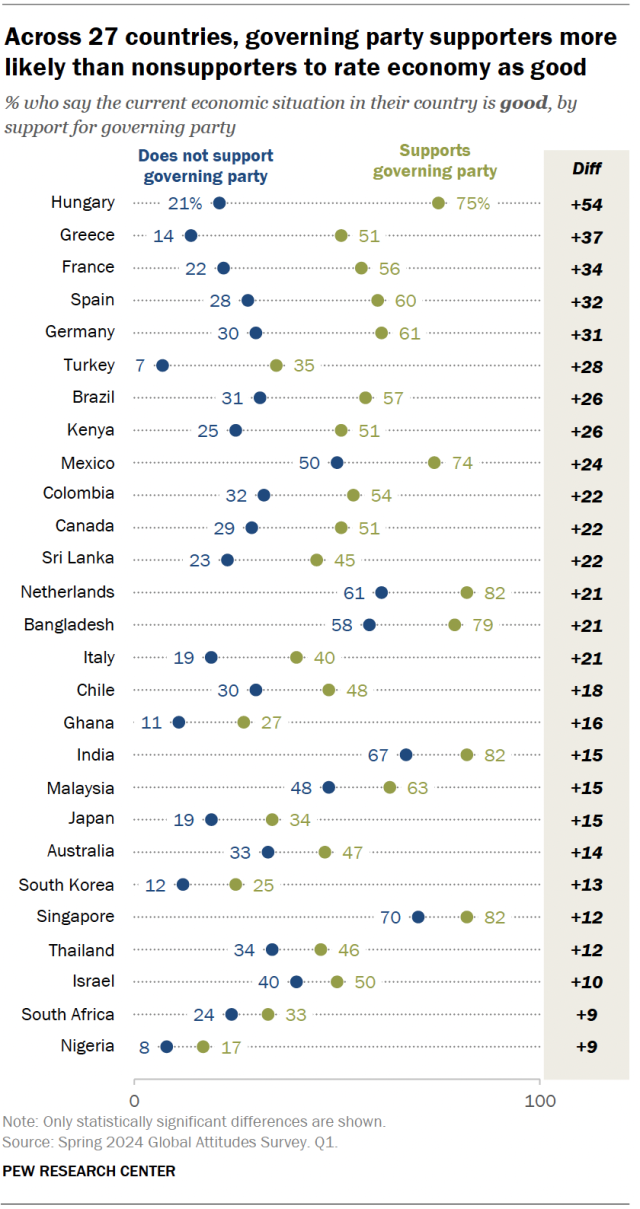

Economic ratings and support for current governments

In general, supporters of a country’s governing party or parties are more likely than nonsupporters to say the current economic situation in their country is good. This pattern holds regardless of whether overall ratings in that country are positive or negative. (Refer to the appendix for country-specific governing party classifications.)

The largest difference is in Hungary, where three-quarters of adults who support the ruling Fidesz-KDNP alliance say the economy is doing well. Just 21% of those who do not support the current government agree.

In France, Germany, Greece and Spain, the difference in economic attitudes between governing party supporters and nonsupporters exceeds 30 points.

Economic ratings by age and education level

The impact of certain demographic factors such as age and level of education on economic ratings varies by country.

In six countries, adults ages 18 to 34 have less positive views of the economy than those 50 and older. But in five countries, the opposite is true. For example, 46% of Chilean adults under 35 feel positively about the current economy, compared with 22% of those 50 and older. But in Sri Lanka, older adults give the country’s economy better ratings than their younger counterparts do (32% vs. 25%).

Similarly, adults with more education rate the economy higher than those with less education in five countries, but in another four countries, it’s less educated adults who are more positive.

Note: Here are the questions used for the analysis, along with responses, and the survey methodology.

CORRECTION (June 7, 2024): A previous version of this post showed Poland data twice in the chart “Across 34 countries, people mostly rate their economies negatively.” The chart has been updated to correctly include data from Sweden. No other findings in the post are affected.