U.S. public school teachers have spent 2024 in the spotlight. The Democratic vice presidential nominee, Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz, has highlighted his previous career as a high school teacher and football coach. And a congressional hearing in June focused on multiple “crises” facing public school teachers, including low pay and overwork.

Here are some key facts about the 3.8 million public school teachers who work in America’s classrooms. These findings primarily come from a fall 2023 Pew Research Center survey of public K-12 teachers and from federal data.

This Pew Research Center analysis focuses on the demographics, experiences and hopes of K-12 public school teachers in the United States.

Demographic data comes from the National Center for Education Statistics and the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Data on teachers’ experiences primarily comes from a Center survey of 2,531 U.S. public K-12 teachers conducted from Oct. 17 to Nov. 14, 2023. This post also draws on our survey of 5,188 U.S. workers conducted from Feb. 6 to 12, 2023; it included both part-time and full-time workers who are not self-employed and have only one job or have more than one but consider one to be their primary job.

More information about each survey, including the questions and methodology, can be found at the links in the text.

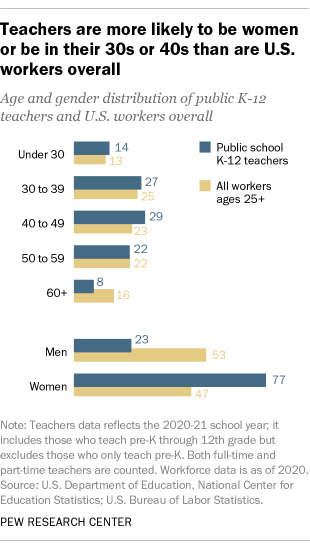

Most K-12 public school teachers are women. About three-quarters (77%) of teachers are women and 23% are men, according to data from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) for the 2020-21 school year, which is the most recent one available. This gender imbalance is especially notable in elementary schools, where 89% of teachers are women. Women make up 72% of middle school teachers and 60% of secondary or high school teachers.

There is far more gender balance among U.S. workers overall, across different industries and occupations. In 2020, women accounted for 47% of workers ages 25 and older, compared with 53% who were men, Bureau of Labor Statistics data shows. “Workers” in this analysis are those ages 25 and older in the U.S. noninstitutionalized civilian population.

The teaching force skews a bit younger than U.S. workers overall. Just 8% of K-12 public school teachers are at least 60 years old, but 16% of U.S. workers are at least 60. Public school teachers are more likely to be in their 30s and 40s than are U.S. workers overall (56% vs. 49%).

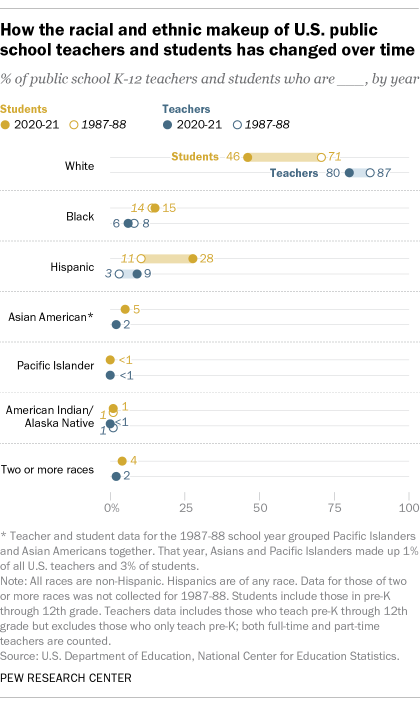

As a group, U.S. public school teachers are considerably less racially and ethnically diverse than their students, according to NCES data. In 2020-21, 80% of public school elementary and secondary teachers identified as non-Hispanic White. Much smaller shares were Hispanic (9%), Black (6%), Asian American or multiracial (2% each). And fewer than 1% identified as Pacific Islander or American Indian and Alaska Native.

By comparison, just under half (46%) of all public school students were non-Hispanic White in 2020. Another 28% were Hispanic, 15% were Black and 5% were Asian. Meanwhile, 4% were multiracial, and about 1% or fewer were American Indian and Alaska Native or Pacific Islander.

The share of the teaching force who is White has declined 7 percentage points between the 1987-88 and 2020-21 school years, but the growth in teachers’ racial and ethnic diversity still has not kept pace with the rapid growth in the diversity of their students over this time span. (Note: In 2021, the Center published a more detailed version of this analysis using the most recent data available at that time.)

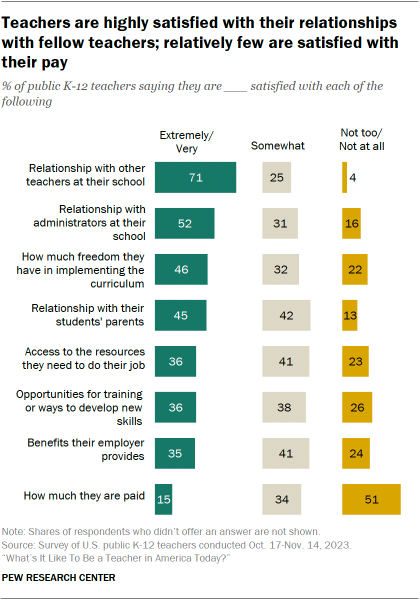

Only a third of teachers say they’re extremely or very satisfied with their job overall, according to a fall 2023 Center survey of public K-12 teachers. About half (48%) say they’re somewhat satisfied, while 18% say they are not too or not at all satisfied with their job.

Teachers express much lower job satisfaction than U.S. workers overall: 51% of all employed adults say they are extremely or very satisfied with their job, according to a separate Center survey conducted in early 2023. (Data for U.S. workers excludes those who are self-employed.)

Teachers are especially dissatisfied with certain aspects of the job, including how much they are paid (51% say they are not too or not at all satisfied); the opportunities for training or ways to develop new skills (26%); and the benefits their employer provides (24%).

In fact, 29% of teachers said it was at least somewhat likely they’d look for a new job in the 2023-24 school year. Among these teachers, 40% said it was at least somewhat likely they’d look for a job outside of education entirely.

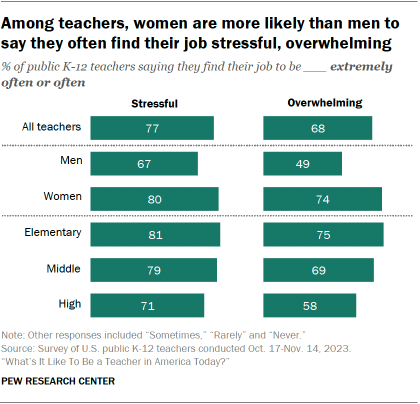

Most teachers describe their job as stressful and overwhelming. Majorities of teachers say they find their job stressful (77%) or overwhelming (68%) extremely often or often. Some teachers are especially likely to experience this:

- Women: 74% of women teachers say they find teaching to be overwhelming extremely often or often, compared with 49% of men. And 80% of women teachers frequently find the job stressful, compared with 67% of men.

- Elementary and middle school teachers: Educators at these levels are more likely than their counterparts at high schools to say that their job is frequently stressful and overwhelming.

Teachers’ negative feelings may be related to the issues they report with understaffing. Seven-in-ten public K-12 teachers say their school is understaffed, with 15% saying it’s very understaffed. Another 55% say their school is somewhat understaffed. This pattern is consistent across elementary, middle and high schools.

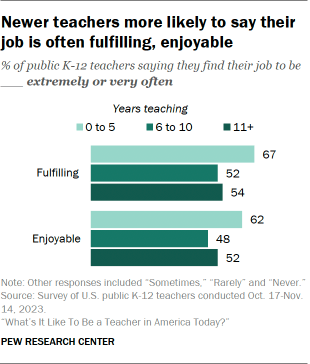

Newer teachers are the most likely to say their job is generally fulfilling and enjoyable. Overall, slim majorities of all K-12 public school teachers say they find their job fulfilling (56%) or enjoyable (53%) extremely often or often.

These sentiments are most common among those who’ve been teaching for less than six years. For instance, 67% of teachers who have been teaching for five years or less say their job is fulfilling extremely often or often. That compares with 52% of teachers with six to 10 years of experience and 54% of those who’ve been teaching for 11 years or more.

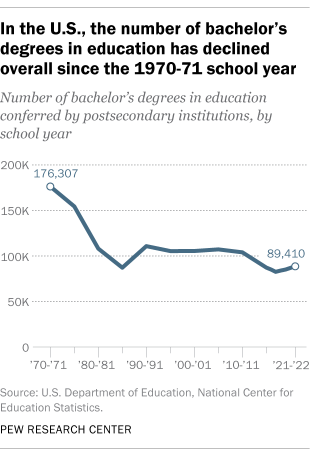

Fewer people are completing the educational requirements to be hired as teachers – just one indicator of the field’s growing pipeline problem, NCES data shows. Many K-12 teachers enter their line of work after getting a bachelor’s degree in education, which includes a teacher preparation program. But some teachers instead meet license requirements through alternative preparation programs, offered through a college or university, state government, nonprofit or other organization.

Both the number and share of new college graduates with a bachelor’s degree in education have decreased over the last few decades. Yet during that span, the overall number and share of Americans with a college degree increased.

In 2021-22, the most recent year with available data, schools conferred about 89,000 education bachelor’s degrees, making up 4% of the total issued that year. In 2000-01, roughly 105,000 undergraduates (8% of the total) graduated with bachelor’s degrees in education.

Teacher preparation programs have also seen a steep decline in enrollment in recent years, including both traditional programs associated with higher-education institutions and alternative ones. Between the 2012-13 and 2020-21 school years, the number of people who completed teacher prep programs dropped from about 190,000 to 160,000. In 2020-21, 13% of those prospective educators received their prep through alternative programs run by organizations other than institutions of higher education.

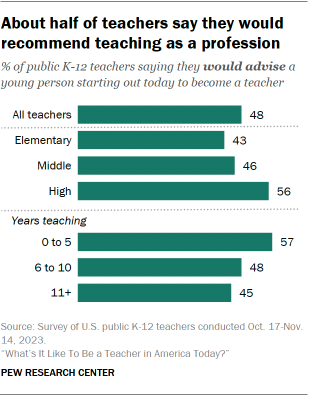

Teachers are relatively split on whether they would advise young people to join the profession, according to the Center’s fall 2023 survey. While 48% say they would recommend the profession to a young person starting out today, 52% say they would not.

High school teachers (56%) are more likely than middle school (46%) and elementary school (43%) teachers to recommend the job. This view is also more common among teachers with five years or less of teaching experience than among more veteran educators.

Teachers rate students in their school fairly low when it comes to academic performance and behavior. About half of K-12 public school teachers say the behavior (49%) and academic performance (48%) of most of students at their school is fair or poor. Meanwhile, just 17% say students’ academic performance is excellent or very good, and 13% say the same about student behavior at their school.

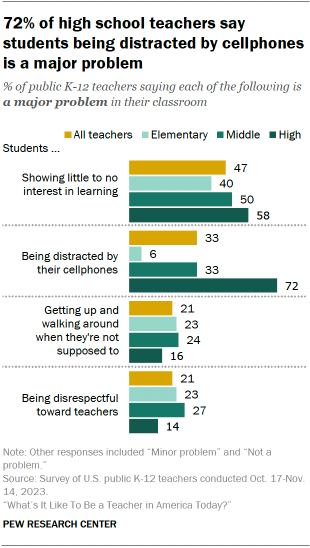

In addition to broader issues at their school, teachers report various challenges in their own classrooms. Teachers across all K-12 grade levels say certain student behaviors are major issues in their classroom:

- Showing little to no interest in learning (47% of teachers say this is a major problem)

- Being distracted by their cellphones (33%)

- Getting up and walking around when they’re not supposed to (21%)

- Being disrespectful toward teachers (21%)

Certain problems are more prevalent for older or younger grade levels. For instance, high school teachers report bigger problems with cellphone distraction (72% say it’s a major problem) and students showing little to no interest in learning (58%). Meanwhile, elementary and middle school teachers are more likely than high school teachers to experience students getting up and walking around or being disrespectful toward teachers.

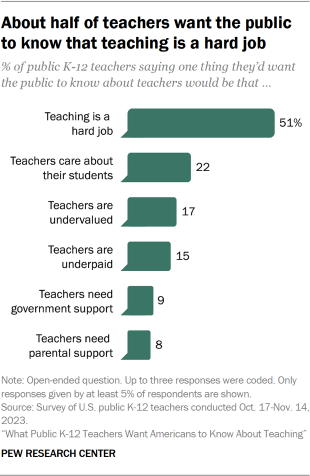

About half of teachers (51%) say that if there’s one thing they want the public to know about them, it’s that teaching is a difficult job and teachers are hardworking. This was the most common response to an open-ended question we asked teachers last fall.

Another 22% of teachers said they want the public to know that teachers care about their students, and 17% want the public to know that teachers are undervalued.