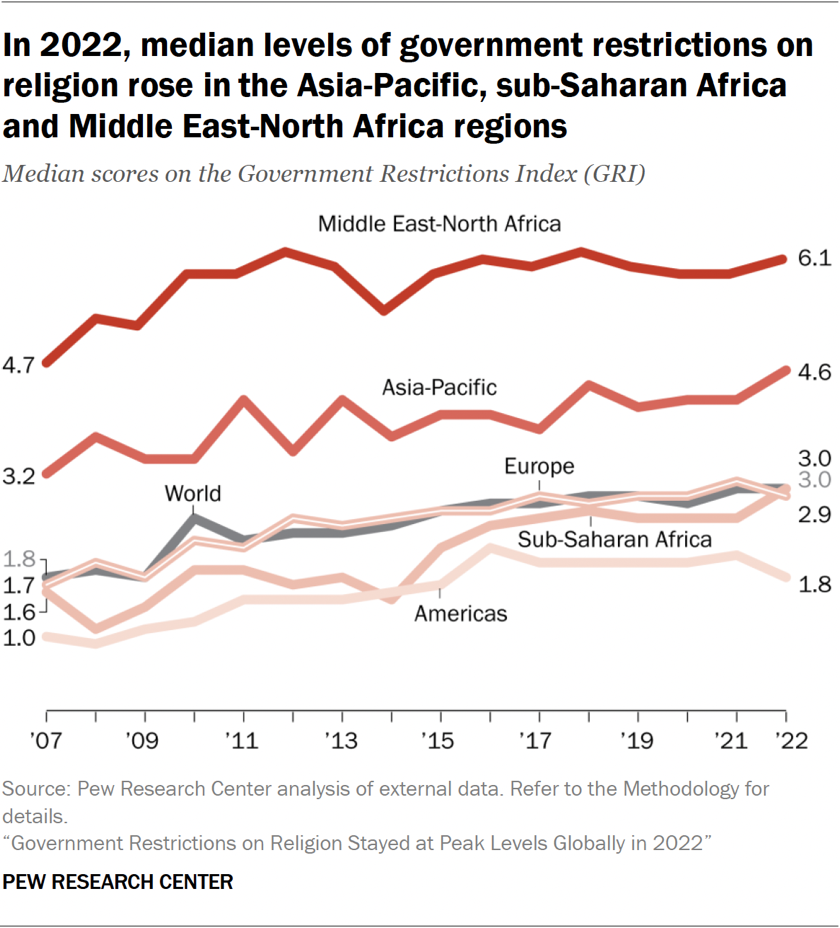

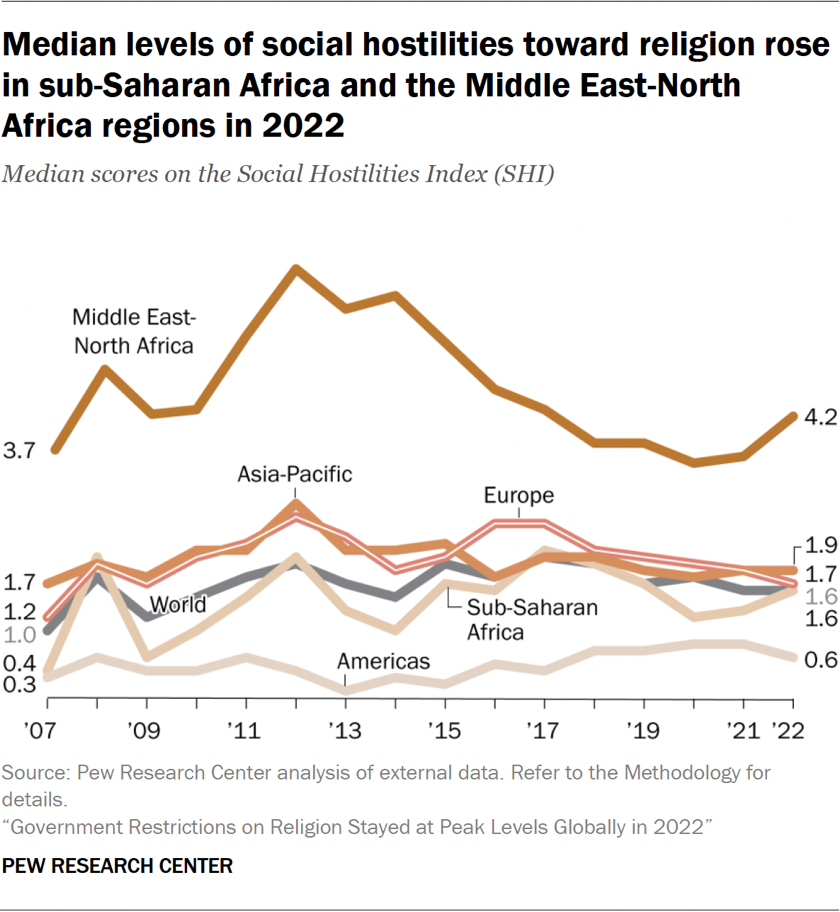

In 2022, global median scores on both the Government Restrictions Index (GRI) and the Social Hostilities Index (SHI) were the same as they were in 2021. Some geographic regions scored higher on one or both indexes, but other regions had lower scores or showed no overall change. This chapter examines the year-over-year changes in the regional scores on both indexes.

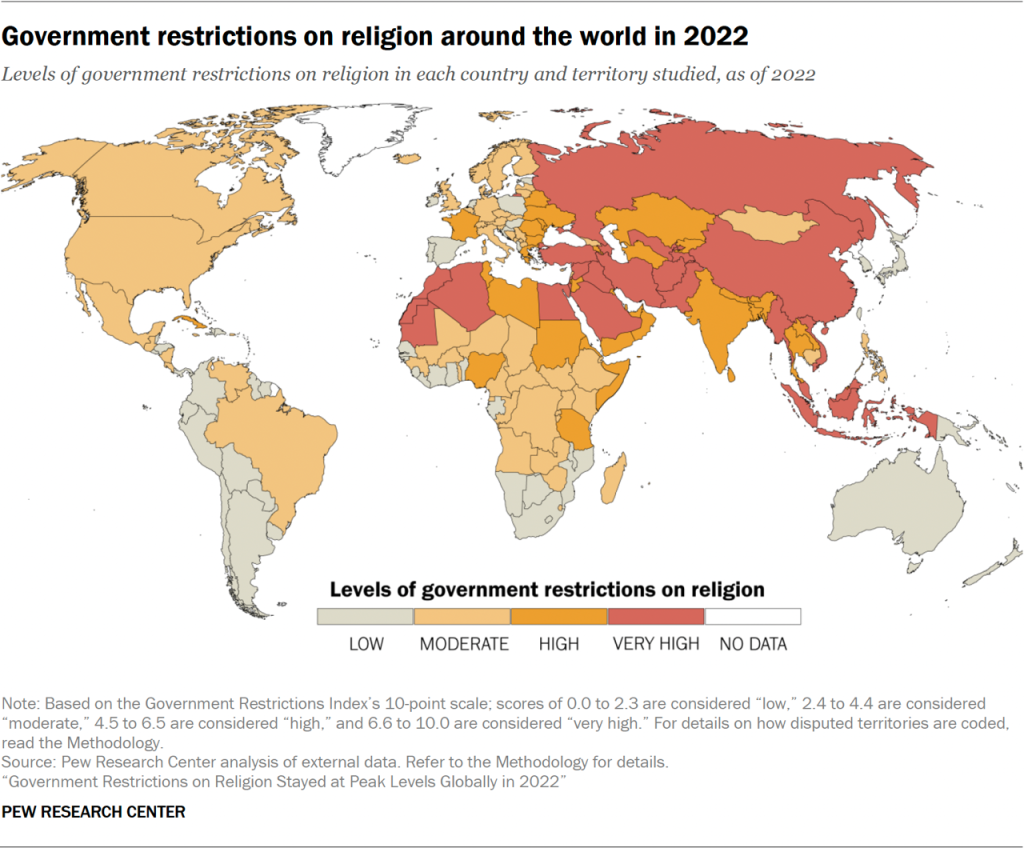

Government restrictions on religion, by region

The global median score for the 198 countries and territories analyzed in this study remained 3.0 out of 10.0 on the Government Restrictions Index, tied for the highest median score registered since 2007, the first year of the study. Median GRI scores increased in three regions – Asia and the Pacific, sub-Saharan Africa, and the Middle East and North Africa – while declining in two regions: the Americas and Europe.

In the Asia-Pacific region, the median GRI score rose from 4.2 to 4.6 in 2022, the highest score in this region since the beginning of the study. More than half of all the countries in the world with “very high” levels of government restrictions in 2022 were in the Asia-Pacific region (14 out of 24).9 In this study, the Asia-Pacific region encompasses 50 countries and stretches across a vast area, from Australia to Turkey. It includes some of the most populous countries in the world, such as India, China and Indonesia.

In 2022, more governments in Asia-Pacific countries interfered in worship, restricted public preaching and used violence against religious groups than in 2021. For example, in Cambodia, a former Buddhist monk was sentenced to five years in prison – and barred from becoming a monk again – for posting messages on social media that were critical of the prime minister. The monk was charged with “conspiracy to commit treason and incitement to commit a felony or cause social unrest.”

In Afghanistan, the Taliban in 2022 were in power for the first full calendar year after having overthrown the previously elected government in August 2021. After their takeover in 2021, the group declared the country an Islamic emirate and ordered that all laws must be in accordance with sharia, or Islamic law. According to the U.S. State Department, minority groups such as the Shiite ethnic Hazara said that the Taliban’s targeting of their community and failure to defend them from attacks by a militant group (ISIS-K) in 2022 “deepened marginalization and the erasure of the Hazara from society.” Other minorities, such as Sikhs, Hindus, Christians and Ahmadi Muslims, sought to leave the country in growing numbers in 2022, fearing the Taliban’s enforcement of sharia.

In 2022, sub-Saharan Africa’s median GRI score increased from 2.6 to 3.0, also hitting its peak level on the index, with nearly all countries in the region (46 out of 48) reporting at least one case of harassment of religious groups. More of these countries interfered in worship, limited public preaching, and used physical violence against religious groups (by detaining religious leaders, for example) in 2022 than did so in 2021.

For example, the government in Equatorial Guinea enforced new mandates requiring religious groups to obtain a “theological certificate” in order to operate, leading some groups to be disbanded, according to the U.S. State Department. Also, an ordained Pentecostal leader in the country, who was a former ambassador and minister, was arrested for criticizing the government and calling it tyrannical. And in Mauritius, 12 Rastafarians were arrested in 2022 for protesting restrictions on marijuana usage in religious ceremonies. Neither of these countries had reports of arrests related to religion in 2021.

The median GRI score in the Middle East-North Africa region climbed from 5.9 to 6.1 in 2022. As has been the case in every year of the study, this region had the highest levels of government restrictions in the study, largely driven by preferential status given to religious groups. Of the 20 countries in the region, all except Sudan recognized a favored or official religion; all except Lebanon required some type of religious education in public schools; and all except Western Sahara had at least one type of physical harassment, according to the sources analyzed.10 And all 20 countries in the Middle East-North Africa region had reports of interference in worship and either physical or verbal harassment (or both types) toward religious groups.

In Oman, for example, authorities sentenced two people – Maryam al-Nuaimi and Abdullah Hassan – to prison for three years and five years, respectively, for online discussions about religious freedom that the government found to be “denigrating Muslim values,” according to the U.S. State Department. And in Morocco, a blogger was fined and sentenced to two years in prison for satirical comments on social media about Quranic verses that authorities charged were “insulting to Islam.” The U.S. State Department reported that the blogger has been held in solitary confinement since her detention.

In 2022, the median GRI score for Europe fell from 3.1 to 2.9, while the score in the Americas fell from 2.1 to 1.8. Of all five major regions, the Americas had the lowest median score for government restrictions in 2022.

In Europe, Russia was the only country with “very high” levels of government restrictions in 2022. According to the U.S. State Department, Russian authorities sentenced people from multiple religious groups to prison on charges of extremism. Those sentenced included Jehovah’s Witnesses, followers of a Turkish Muslim theologian named Said Nursi, and members of Falun Gong (an illegal religious group), the Church of Scientology, evangelical Protestant groups, and a transnational Islamic political group called Hizb ut-Tahrir. Russian Orthodox priests and members of other religious groups also were fined and banned from their positions for criticizing the Russian government’s war in Ukraine.

In the Americas, Cuba was the only country with “high” GRI levels in 2022, while all other countries in the region had “moderate” or “low” scores. According to the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF), the Cuban government restricted the freedom of religious groups “through surveillance, harassment of religious leaders and laypeople, forced exile, fines and ill treatment of religious prisoners of conscience.” In February, the president of the Christian Reformed Church of Cuba was detained because his denomination had disaffiliated with a pro-government council of churches. He left the country for the United States later in the year.

And in the U.S., which had “moderate” levels of government restrictions in 2022, multiple cases remained open from previous years involving complaints of religious discrimination filed under the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act, a federal law. For example, the American Civil Liberties Union of Mississippi filed a lawsuit in November 2021 alleging that city officials in Horn Lake, Mississippi, denied zoning permits for construction of a mosque “due to anti-Muslim bias.”

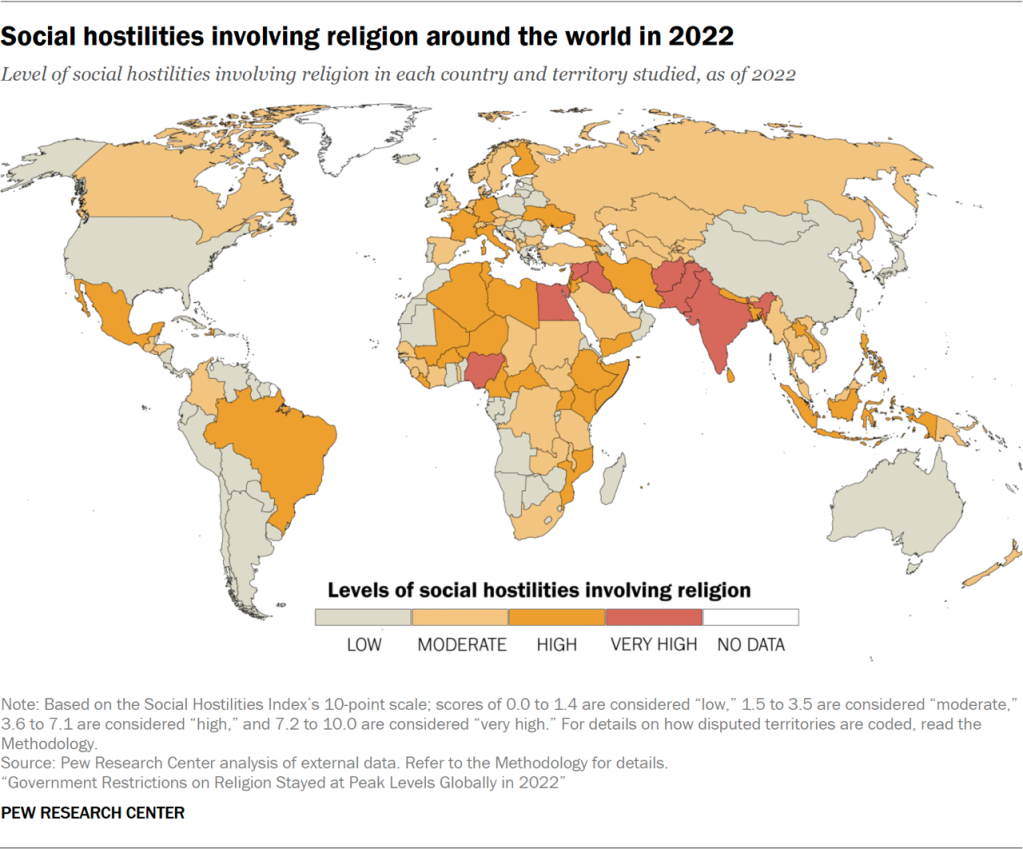

Social hostilities involving religion, by region

The global median score on the Social Hostilities Index was stable in 2022, remaining at 1.6 out of 10.0, the same as in 2021. The Middle East-North Africa region and sub-Saharan Africa registered increases, while the Americas and Europe had declines in their median SHI scores. The Asia-Pacific region’s median score stayed the same.

In the Middle East-North Africa region, the median SHI score rose from 3.6 to 4.2. Syria, Iraq and Egypt had the highest social hostilities scores in the region, with all three countries in the “very high” category.

Syria in 2022 continued to experience the aftereffects of broad conflicts dating back to anti-government protests that broke out in the Arab Spring of 2011. The U.S. State Department said the country was afflicted by sectarian violence “exacerbated by regime actions” and accused the Syrian government of using “sectarianism, including the politicization of religion” to its advantage in 2022.

Iraq also experienced sectarian instability rooted in a long series of events, including the U.S. invasion of the country in 2003; the subsequent rise of the Sunni militant group Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) in 2013-14; and the formation of predominantly Shiite armed groups known as Population Mobilization Forces (PMF) to fight ISIS. In 2022, media and human rights organizations said security conditions were improving in Iraq but also reported that “sectarian armed groups” (such as militias aligned with Iran) carried out violence and that people in non-Muslim minority religious groups faced kidnappings and pressure to follow Islam.

The median SHI score in sub-Saharan Africa increased from 1.3 to 1.6 in 2022, with Nigeria, Burkina Faso and Mali recording the highest SHI scores in the region. Nigeria had “very high” levels of social hostilities, while Burkina Faso and Mali had “high” levels.

In 2022, Burkina Faso faced a worsening security climate due to multiple military coups and the expansion of armed insurgents and jihadist militant groups such as the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara. These groups killed religious leaders and worshippers and attacked mosques, churches and places where animists worship, according to the U.S. State Department, which also reported that the expansion of extremist groups threatened the country’s “long tradition of religious pluralism.” For example, the Fulani ethnic group, which is mostly Muslim, faced violence from other ethnic groups because of a “perceived association with militant Islamist groups.”

Mali also dealt with violent attacks in 2022, as militant groups targeted civilians, government forces and peacekeepers for not following their strict interpretation of Islam, according to the U.S. State Department. These groups – designated by authorities as extremists – shut down government schools they viewed as overly Western and directed that some of them become schools focused on teaching the Quran.

Meanwhile, the median SHI score across Asia and the Pacific remained stable at 1.9 in 2022. India, Pakistan and Afghanistan had the highest levels of social hostilities in this region; all registered SHI scores in the “very high” category.

In India, several deadly incidents of communal violence took place in 2022, particularly between Hindus and Muslims over accusations that Muslims had slaughtered or sold cows, which Hindus view as holy. The U.S. State Department reported that a Muslim man was beaten to death and two others were injured by a mob in the state of Madhya Pradesh in August for “transporting cattle for slaughter,” which is illegal in the state. While police filed a complaint against the accused perpetrators of the attacks, they also charged the two injured Muslim survivors for “illegally transporting cattle.”

And in Pakistan, a Muslim-majority country, religiously motivated attacks claimed the lives of Muslims as well as Hindus, Christians and Sikhs. For example, in February, a mob severely beat and killed a mentally disabled Muslim man and hung his body from a tree after he was accused of burning pages of a Quran. Police officers responding to the attack allegedly were assaulted by the mob as well. The police eventually arrested more than 30 people and held more than 100 for questioning.

In 2022, Europe’s median score for social hostilities fell from 1.9 to 1.7 in 2022. And in the Americas, the median SHI score also ticked downward, from 0.8 to 0.6. Still, religious groups faced harassment (verbal or physical) by social actors in 4o out of the 45 countries analyzed in Europe. And in 20 European countries, women were harassed for violating either secular or religious dress norms, according to the study’s sources.

For example, in a survey conducted by the government, Muslim women in the Netherlands who wore face coverings reported facing rising social harassment after the country banned face coverings in 2019, which included religious attire such as niqabs and burqas. Another survey found that women who wear head coverings in job application photos have a lower chance of being called back by employers.