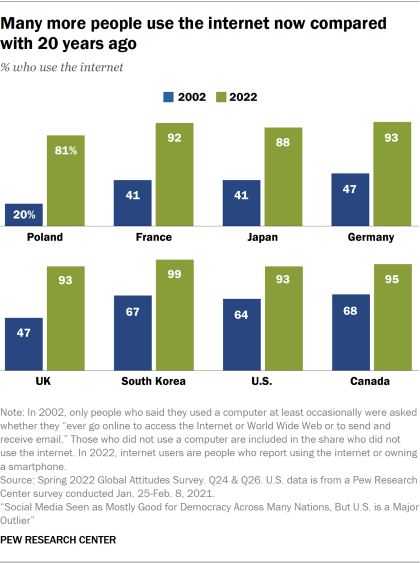

Pew Research Center first started asking about internet use internationally in 2002. Twenty years later, internet use among adults in several countries has increased dramatically. The way people use and access the internet has changed since then, so our question has changed as well. In 2002, we first asked whether people used a computer at least occasionally, either at home, work or school. People who reported using a computer then indicated whether they “ever go online to access the Internet or World Wide Web or to send and receive email.” A median of 47% reported using the internet across eight countries: Canada, South Korea, the U.S., Germany, the UK, France, Japan and Poland.

Among the countries included in the analysis, a few people used a computer without using the internet in 2002, ranging from 6% in South Korea to 18% in France, but a substantial share of the population in some of the countries did not use a computer at all. Poland had the highest share of the population who did not use a computer (67%). Even in the countries with the highest prevalence of computer use – the U.S., Canada and South Korea – roughly 25% reported never using a computer.

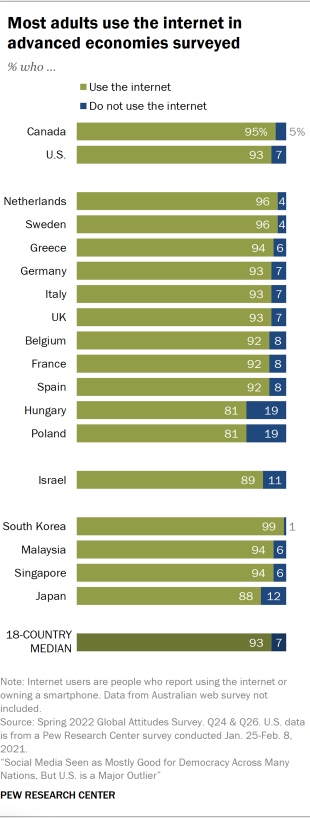

By comparison, a median of 93% among these countries report using the internet in the current survey. In fact, the overwhelming majority of people surveyed across 18 countries report using the internet, at least occasionally. (Although we surveyed in Australia, we do not include it in this analysis because data was collected online and mode differences prevent direct comparisons.) Because smartphones have access to the internet, people who own a smartphone are also classified as internet users, whether they say they use the internet or not. The share of people who report not using the internet ranges from 1% in South Korea to 19% in both Poland and Hungary, though in most countries, this share is in the single digits.

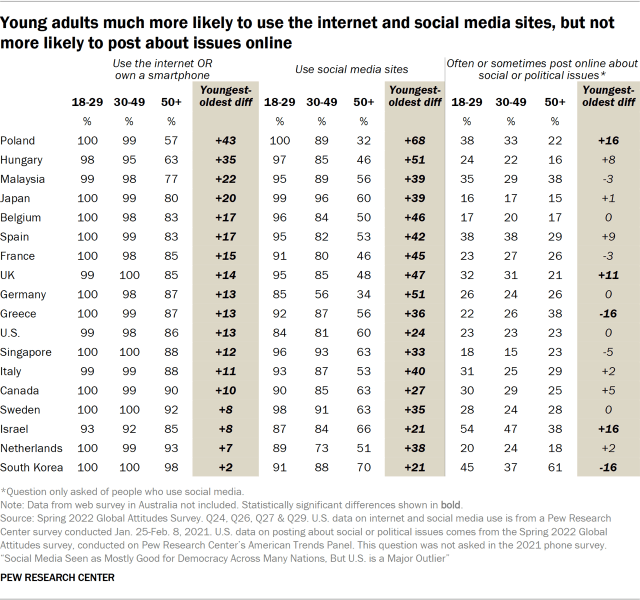

Internet use varies based on age, education and income. Nearly 100% of young adults report using the internet in every country except Israel (93%). Among older adults, internet usage rates range from 57% in Poland to around nine-in-ten in Canada (90%), Sweden (92%) and the Netherlands (93%). Older Koreans stand out, with 98% reporting using the internet.

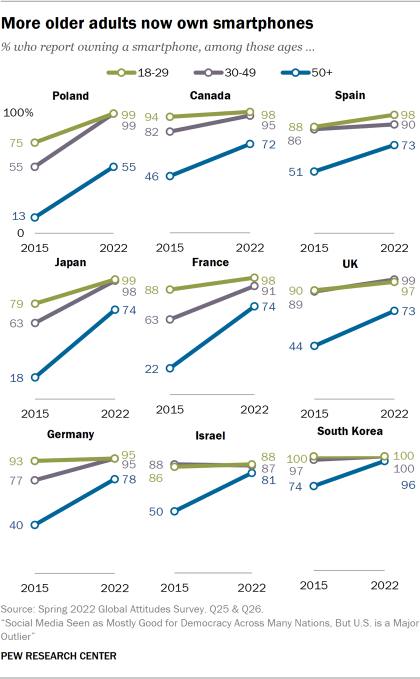

Age differences within most countries in the analysis have become smaller over time as internet use has increased sharply among older adults. For example, 82% of German adults under 30 used the internet in 2002 compared with only 22% of Germans ages 50 or older, a 60 percentage point age gap. In the current survey, most Germans of all age groups report using the internet, including 100% of young adults and 87% of older adults.

People with more education and those with a higher income are also more likely to use the internet in nearly every country surveyed. In Israel, for example, 71% of people with a lower income report using the internet, compared with 96% of those with a higher income. And 85% of Israelis with less education use the internet, compared with 95% of those with more education.

Widespread smartphone ownership while very few do not own a mobile phone at all

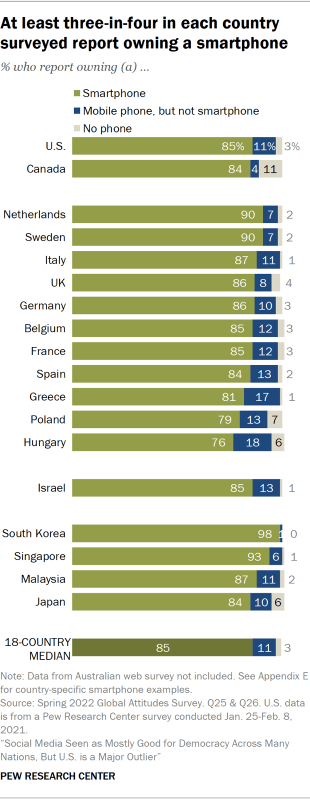

Nearly all people surveyed across 18 advanced economies report owning a mobile phone, the vast majority of which are smartphones. A median of 85% say they own a smartphone, 11% own a mobile phone that is not a smartphone and only 3% do not own a phone at all. (See Appendix E for a list of country-specific smartphone examples.)

Despite widespread smartphone ownership, there is some variability across the countries surveyed in mobile tech use. Roughly 20% of adults in Greece and Hungary own a mobile phone that is not a smartphone. And about 10% do not own a mobile phone at all in Canada and Poland. On the opposite end of the spectrum, 98% of Korean adults own a smartphone. (See the “How we did this” section of this report for more information about how reported tech usage is related to our survey methodology.)

There are also large differences in smartphone and mobile phone ownership within each country, with younger adults, people with a higher income, and those with more education generally being more likely to own a smartphone.

In Poland and Hungary, where somewhat fewer people overall own a smartphone, there are especially large gaps. Nearly all Polish young adults own a smartphone (99%), compared with just over half of people ages 50 and older (55%). Similarly, 98% of people with higher education and 87% of those with higher incomes in Poland own a smartphone. But among Poles, only 73% with less education and 49% with lower incomes report owning a mobile phone that is a smartphone. The differences based on age and income look roughly the same in Hungary. In nearly every other country surveyed, there are significant, but smaller gaps.

As with internet use, the age gap in smartphone ownership in these countries has narrowed over time as more older adults have adopted smartphones. In Canada, for example, the share of young adults who own a smartphone has not changed much since 2015, but among older adults, the share has increased from 46% to 72% in the current survey. In South Korea, where nearly everyone in all age groups reports owning a smartphone, ownership among older adults has grown substantially since 2015, when this question was first asked.

Trends in the U.S. show a similar pattern for tech use among older adults over the last decade. While smartphone ownership has increased among all age groups in the U.S. since 2012, Americans ages 65 and older have seen an especially sharp uptake in smartphone ownership, increasing from 13% in 2012 to 61% in 2021.

Previous Pew Research Center surveys have found that smartphone penetration is lower in some emerging and developing economies. In 2018, the median share who reported owning a smartphone across 19 lower- or middle-lower income countries was 42%, though most adults reported owning a mobile phone. And as in the advanced economies surveyed, younger adults and those with more education and a higher income are much more likely to own a smartphone in these countries.

Most say they use social media sites

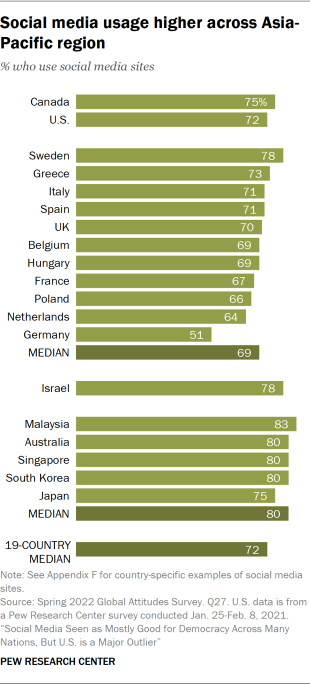

At least half in every country surveyed say they ever use social media sites such as Facebook, Twitter or Instagram (see Appendix F for full list of country-specific examples of social media sites). Social media use is especially common across the Asia-Pacific countries surveyed (median of 80%), but still widespread in Europe (median of 69%), Israel, Canada and the U.S.

Germans stand out for having less prevalent social media use. Only around half of Germans use sites like Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. By comparison, roughly two-thirds or more report using social media in every other country surveyed.

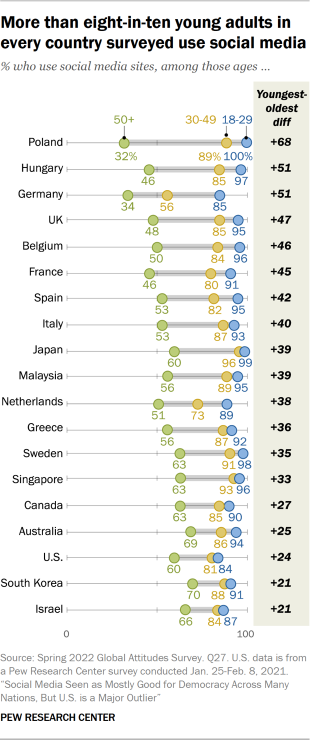

Age gaps in social media use between those under 30 and those 50 or older are 20 percentage points or higher in every country surveyed. Poland is a particularly stark example, with 100% of younger adults but only 32% of older adults reporting using social media.

Social media use among older adults ranges widely. Half or fewer of adults ages 50 or older use social media in Poland, Germany, France, Hungary, the UK or Belgium. Roughly two-thirds or more of older adults use social media in Israel, Australia and South Korea. Social media usage among younger adults, on the other hand, ranges from 84% in the U.S. to 100% in Poland.

Though younger adults are more likely than older adults to use social media, there is evidence that the age gap in social media use has narrowed over time. There has been a faster rate of change in social media use among older adults in a number of countries, similar to internet use and smartphone ownership. For example, social media use among young adults in the UK has not changed since 2012 (since most young adults were already using social media a decade ago). By comparison, it has more than doubled among people ages 50 and older in the UK, from 22% who used social media in 2012 to 48% in the current survey.

The question asked whether people use any social media sites, but data from the U.S. demonstrates that the popularity of different sites varies widely. In a 2021 survey, 69% of Americans reported ever using Facebook, while 40% said they used Instagram, 23% used Twitter and 21% used TikTok. Younger adults are generally more likely to use social media sites, but the magnitude of the age difference depends on the platform.

Internet and social media use in lower-income countries

Pew Research Center suspended fieldwork in countries where surveys are conducted in person at the start of the coronavirus pandemic in early 2020. We plan to return to these countries, many of which are emerging or developing economies, as health outcomes continue to improve around the world. Yet, because of this, the current survey focuses on internet use and attitudes in advanced economies.

We last asked about technology use in a larger set of countries in 2019. Rates of internet use at that time were lower in some emerging and developing economies, though at least half in most countries reported using the internet or owning a smartphone. India was an outlier among the countries surveyed (38%). Because relatively fewer people in several of these countries used the internet, social media use was generally lower, as well.

The 2019 survey also showed the same demographic patterns we see in the current survey: Younger adults and people with more education or a higher income are all more likely to use the internet and social media. These differences tend to be largest in many lower-income countries where overall usage rates are lower.

Surveys of Americans during the coronavirus pandemic found that a majority see the internet as essential in their lives and many reported using the internet in new ways as a result of the outbreak. Pew Research Center is planning to collect new data in emerging and developing countries in our next annual global survey to shed light on whether, and in what ways, technology use in these countries has changed since 2019.

Frequent posting about social or political issues on social media is uncommon

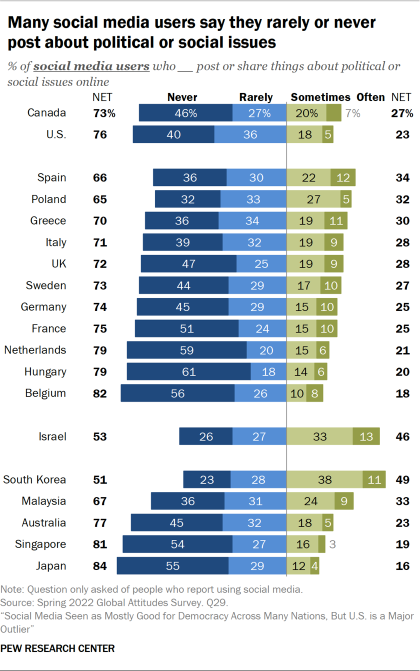

Despite most people reporting using social media sites, few say they post or share things about political or social issues on social media with any frequency. A median of 73% of social media users across the 19 countries surveyed say they rarely or never post about issues on social media. A median of just 27% say they sometimes or often do.2

The most common response across many of the countries surveyed is that people never post or share about political or social issues online. This includes roughly half or more of people who use social media in the UK, France, Singapore, Japan, Belgium, the Netherlands and Hungary.

Posting about social issues is relatively common in some countries, however. Almost half of social media users in Israel and South Korea say they post or share about social or political issues at least sometimes. And roughly a third say the same in Spain, Malaysia, Poland and Greece.

Notably, while there are significant age gaps in tech use, older adults are generally just as likely as younger adults to post online about social or political issues. Thus, while more people ages 18 to 29 are on social media to begin with, that does not necessarily translate to them being more active when it comes to sharing about politics online. There are some exceptions. Among social media users, younger adults are more likely than those ages 50 and older to post about social issues in Poland, Israel and the UK. And older adults are more likely than younger ones to post or share things about these issues in Greece and South Korea. Yet overall, posting about social or political issues on social media is rare among all age groups.

Similarly, while there are differences in smartphone ownership and internet and social media use based on education and income, there are no differences in who decides to post online about social or political issues.

There are some differences based on where people place themselves on the political spectrum, however. In the U.S., Italy, Spain, Australia and South Korea, people on either end of the ideological spectrum are more likely to post than those who place themselves in the center. In the U.S. for example, 29% of self-identified liberals and 25% of conservatives post about social issues at least sometimes, while only 19% of moderates say they post with the same frequency. Spain has some of the largest differences based on ideology: Roughly 40% of those on the ideological right and left post about issues online, compared with about a quarter of people in the center of the political spectrum. And in France, those on the ideological left are more likely to post about social or political issues (38%) than those in the center (21%) or on the right (21%).

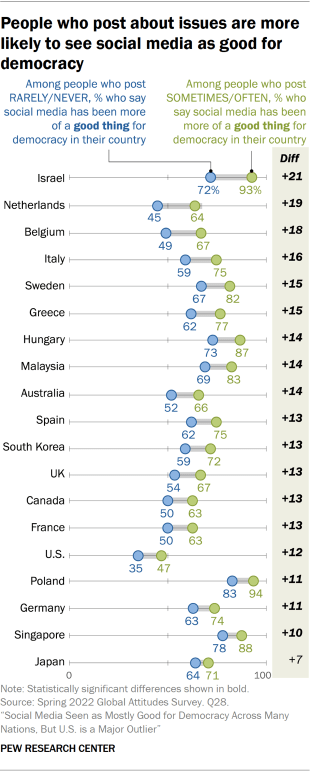

People who post online and those who do not also differ in their attitudes about social media’s influence on society and democracy. In nearly all countries surveyed, those who post about social or political issues on social media at least sometimes are more likely than people who do not post to say that, all things considered, social media has been more of a good thing for democracy in their country. This is true even in the U.S., where most do not feel social media has been good for their democracy; among those who post about social or political issues sometimes or often, 47% say social media is good for democracy, compared with 35% among those who rarely or never post about these issues.

In most places surveyed, people who post online about social or political issues are also more likely to see social media as an effective way to influence policy decisions, raise awareness or change people’s minds about social or political issues, or get elected officials to pay attention to those issues. In every country except Germany, more people who post about issues online, compared with those who don’t, say that in order to be a good member of society it is very important to join demonstrations about important issues. In some places, those who make social or political posts also place more importance on following domestic and international news.

In seven countries, people who are dissatisfied with their democracy are more likely to share or post about political or social issues on social media. In France, for example, 33% of people who are dissatisfied with the way democracy is working in their country post about issues often or sometimes, compared with only 16% of those who are satisfied with democracy. A similar patten can be seen in the Netherlands, Canada, Greece, the UK, Australia and Singapore. But a negative view of their political system is not the only potential driver of posting about issues online. In several countries, people who have a higher sense of political efficacy, meaning those who feel their political system allows them to have some say in politics, are also more likely to post.

Spotlight on the U.S.: Political discussions online

Americans tend to be somewhat exhausted by how much political content they see on social media, at least during election years. A 55% majority of adult social media users described themselves in 2020 as “worn out” by how many political posts and discussions they saw – up 18 points since the question was fielded in the lead up to the 2016 election. Seven-in-ten social media users also said that talking about politics on social media with people they disagree with tends to be stressful and frustrating – rather than interesting and informative – and that share had also grown since 2016.

When asked in 2020 whether they post about political or social issues, 70% of Americans said they did not. The chief reasons these non-posters gave for their behavior was that they didn’t want things they posted or shared to be used against them (33%) and they didn’t want to be attacked for their views (32%) – more than said the same of not wanting to offend others (20%).

As of 2021, around one-in-five Americans reported having experienced online harassment because of their political views.

A 2021 analysis of Twitter users in the U.S. also found that people who tweet frequently about political issues (just 6% of U.S. adults with public Twitter accounts) are more politically engaged than others in a number of ways: They are more likely to have attended a political rally or event, or contacted an elected official, and they are much more likely to follow the news most of the time. Consistent with the finding that both liberals and conservatives are more likely to post about political or social issues in the U.S., the analysis found that prolific political tweeters were more likely to identify as either liberal or conservative and tended to have more negative ratings of people who support a different political party.

The Center has also found in surveys of U.S. adults that a majority distrust social media sites as sources of political and election news, believe social media has a negative impact on the “way things are going” in the country and believe the firms running the platforms censor political viewpoints.