Dissatisfaction with functioning of democracy is linked to concerns about the economy, the pandemic and social divisions

This Pew Research Center analysis focuses on views of democracy and the desire for political, economic and health care reform. For this report, we conducted nationally representative surveys of 16,254 adults from March 12 to May 26, 2021, in 16 advanced economies. All surveys were conducted over the phone with adults in Canada, Belgium, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, the United Kingdom, Australia, Japan, New Zealand, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan.

In the United States, we surveyed 2,596 U.S. adults from Feb. 1 to 7, 2021. Everyone who took part in the U.S. survey is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories.

This study was conducted in places where nationally representative telephone surveys are feasible. Due to the coronavirus outbreak, face-to-face interviewing is not currently possible in many parts of the world.

Here are the questions used for the report, along with responses. See our methodology database for more information about the survey methods outside the U.S. For respondents in the U.S., read more about the ATP’s methodology.

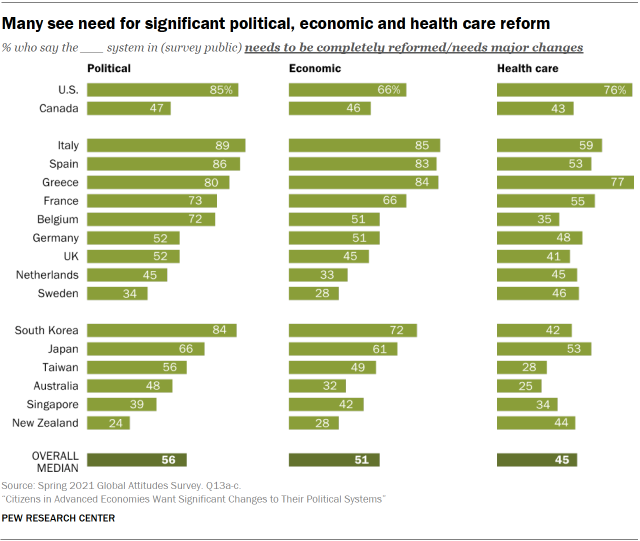

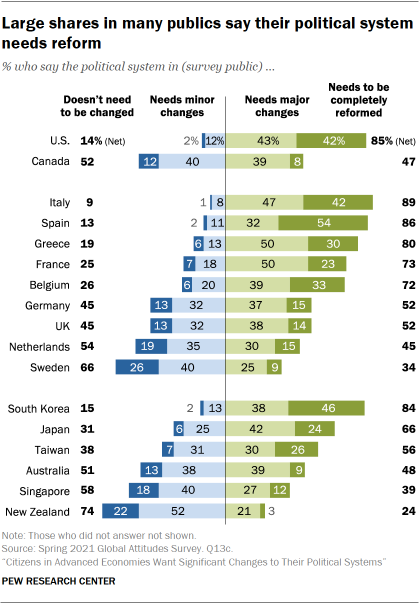

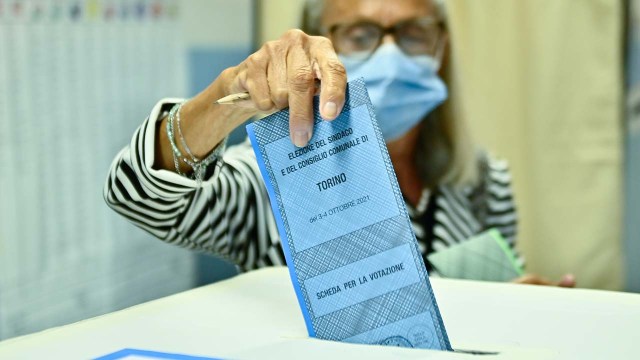

As citizens around the world continue to grapple with a global pandemic and the changes it has brought to their everyday lives, many are also expressing a desire for political change. Across 17 advanced economies surveyed this spring by Pew Research Center, a median of 56% believe their political system needs major changes or needs to be completely reformed. Roughly two-thirds or more hold this view in Italy, Spain, the United States, South Korea, Greece, France, Belgium and Japan.

Even in places where the demand for significant political reform is relatively low, substantial minorities say their system needs minor changes. In all of the publics surveyed, fewer than three-in-ten say the political system should not be changed at all.

But while many want change, many are also skeptical about the prospects for change. In eight of the 17 publics, roughly half or more of those polled say the political system needs major changes or a complete overhaul and say they have little or no confidence the system can be changed effectively.

There is also a strong desire for economic reform in many of the publics surveyed. In Italy, Spain and Greece – three countries where the economic mood has been mostly dismal for over a decade – at least eight-in-ten of those polled believe their economic systems need major changes or a complete overhaul. About three-quarters in South Korea and two-thirds in the U.S. and France share this sentiment.

In comparison, there is less demand for changes to health care systems. But the U.S. and Greece are clear outliers: About three-quarters of Americans and Greeks say their health care system needs major changes or needs to be completely reformed.

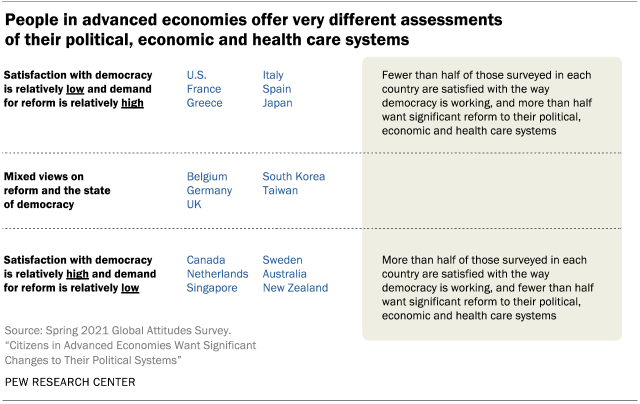

These questions about political, economic and health care reform reveal very different public moods across the advanced economies surveyed. There are six nations – the U.S., Italy, Spain, Greece, France and Japan – where discontent with the status quo is especially high. In all six, more than half want major changes or complete reform to the political, economic and health care systems.

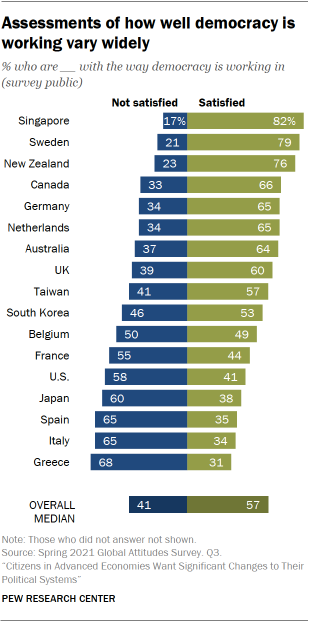

Satisfaction with the way democracy is working is also lowest in these countries. Fewer than half of adults in Greece, Italy, Spain, Japan, the U.S. and France are satisfied with the functioning of democracy in their country.

However, the public mood is not so downcast everywhere. Majorities in half of the surveyed publics express satisfaction with the state of their democracy. And there are six nations – Canada, the Netherlands, Sweden, Australia, Singapore and New Zealand – where the desire for reform is relatively low. (Organizations that provide cross-national ratings of democracy generally give Singapore lower ratings than the other nations in the survey. For more on how the Economist Intelligence Unit, Freedom House and the Varieties of Democracy project rate all 17 places polled, see Appendix A.) Fewer than half of those surveyed in all six countries want significant reform to their political, economic or health care systems. Satisfaction with democracy is also notably high in these nations.

The impact of economic assessments

Attitudes toward the state of democracy and political reform are shaped in part by views about the economy, the impact of COVID-19 and social and political divides.

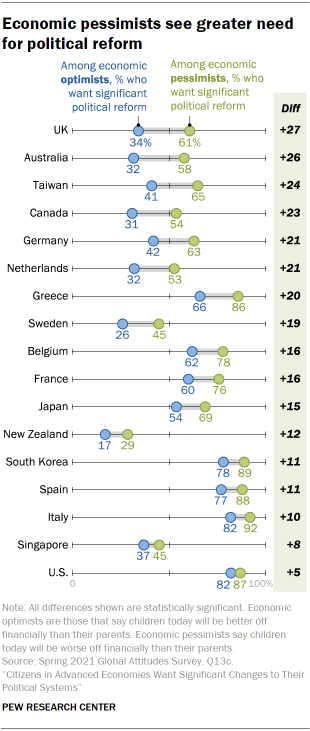

People who describe the current economic situation in their country as bad are consistently more likely than those who describe it as good to say they are dissatisfied with the way democracy is working. And in 16 publics, they are more likely to want significant political reform.

Similarly, optimism or pessimism about the long-term economic future for children is linked to attitudes toward political reform. In the societies polled, those who think children in their country today will be financially worse off than their parents are especially likely to say their political system needs major changes or complete reform.

In the United Kingdom, for example, 61% of respondents who are pessimistic about the next generation’s financial prospects think their country needs significant political reform, compared with just 34% among those who are optimistic that the next generation will do better financially than their parents.

Opinions about the current and future state of the economy are also tied to views about economic reform. People who say the current national economic situation is bad and those who are pessimistic about the financial prospects for today’s children are generally more likely to call for significant changes to their economic system.

COVID-19 and views about the state of politics

The coronavirus pandemic has influenced politics and public opinion around the globe. As previous Pew Research Center reports have shown, a growing number of people in advanced economies report that their lives have changed significantly as a result of the pandemic. Our analysis also shows that opinions about the impact of COVID-19 are shaping attitudes toward democracy and the need for reform.

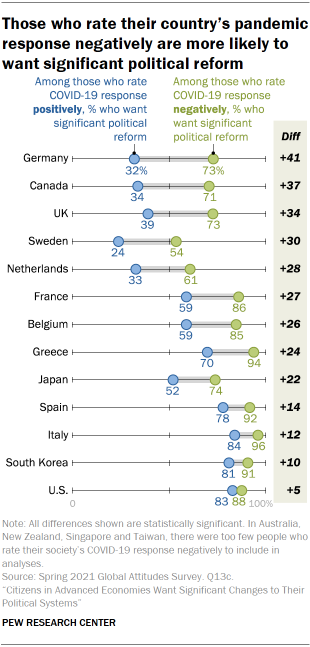

People who believe their country is doing a poor job of dealing with the pandemic are consistently more likely to say they are dissatisfied with the way their democracy is working and to call for political reform.

For instance, 73% of Germans who feel their country is handling the crisis poorly believe their political system needs major changes or should be completely overhauled, while just 32% of those who think the country is handling it well express this view.

The belief that one’s country is doing a bad job of dealing with the pandemic is also linked to a desire for health care reform. In the U.S. – where the demand for reform is relatively high – 86% of those who think the country has handled the pandemic poorly want significant change in the American health care system; 62% of those who say the U.S. has done a good job dealing with the pandemic want significant change.

Another key finding from our earlier reporting on COVID-19 is that growing shares of the publics in advanced economies believe their country is more divided than before the outbreak. We also find that this belief about people now being more divided is linked to attitudes about the political system. People who think their country is more divided since the outbreak are particularly likely to be dissatisfied with the state of democracy and to want political reform.

Divided societies and political reform

The pandemic has exacerbated long-running divisions in countries around the globe, and as a recent Center report found, many people in these 17 advanced economies see significant partisan and racial and ethnic conflict in their societies.

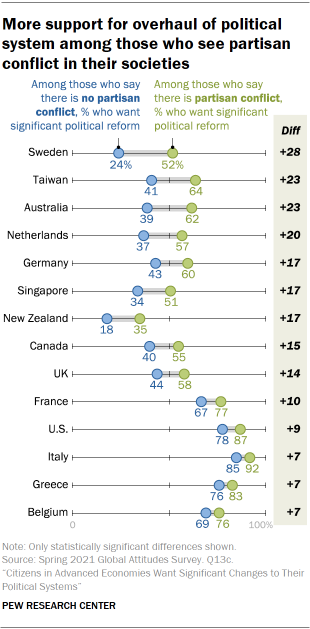

Perceptions of partisan divisions – which are especially common in South Korea and the U.S., where nine-in-ten see conflict between people from different political parties – are linked to unhappiness with the state of democracy and a strong desire for political reform.

Sweden is a nation where the demand for political reform is low overall, but among those who say there is significant partisan conflict in their country, 52% think the political system needs major changes or should be overhauled completely; only 24% of Swedes who do not believe there is partisan conflict in their country say their political system needs significant reform. Similar gaps between those who see partisan conflict and those who do not are also found in 13 other publics surveyed.

Beyond partisan disagreements, at least a quarter in many places say most people disagree about basic facts on important issues facing their country (in France, the U.S., Italy, Spain and Belgium, about half or more say this). And the desire to reform the political system is especially common among those who see widespread disagreement over basic facts. For instance, 69% of Dutch respondents who say there is disagreement about basic facts want significant political reform, compared with just 37% of those who believe people generally agree about facts.

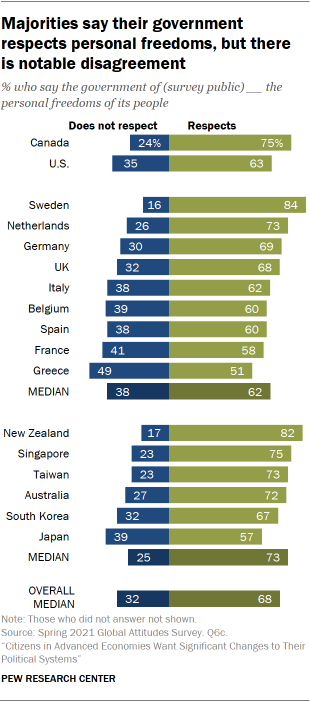

These are among the major findings of a Pew Research Center survey, conducted from Feb. 1 to May 26, 2021, among 18,850 adults in 17 advanced economies. The survey also finds that at least half in every public surveyed say their government respects the personal freedoms of its people. Still, about a third or more of those polled in Greece, France, Japan, Belgium, Spain, Italy and the U.S. say their government does not respect personal freedoms.

Widespread support for political reform in many publics

Roughly half or more in 13 of 17 publics surveyed say their political system needs at least major changes. A median of 38% say their system needs major changes, while 23% say it needs to be completely reformed.

In Spain, South Korea, the U.S. and Italy, four-in-ten or more say their political systems need to be completely reformed. And in nearly all places, roughly a third or more of people say major changes are needed.

In contrast, most of those surveyed in New Zealand, Sweden, Singapore, the Netherlands, Canada and Australia think their political systems need either minor changes or no changes at all.

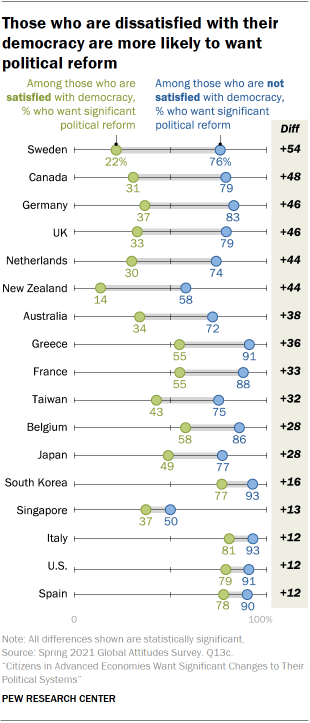

Those who are dissatisfied with democracy are consistently more likely to say that their political system needs at least major changes. These differences are double digits in every place surveyed but tend to be largest in nations where large majorities are satisfied with democracy, such as Sweden and Canada, and smaller where fewer are satisfied with democracy, such as the U.S. and Italy.

In the U.S., large majorities of both Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents (88%) and Republicans and Republican-leaning independents (83%) support major changes or complete reform. Roughly half of Democrats (47%) think the political system needs to be completely reformed, compared with 38% of Republicans.

In 14 publics, people who support the governing party are less likely to want significant political reform. The U.S. is the only country where this pattern is reversed. (The U.S. survey was conducted in early February 2021, only a couple weeks after Joe Biden was inaugurated as president.)

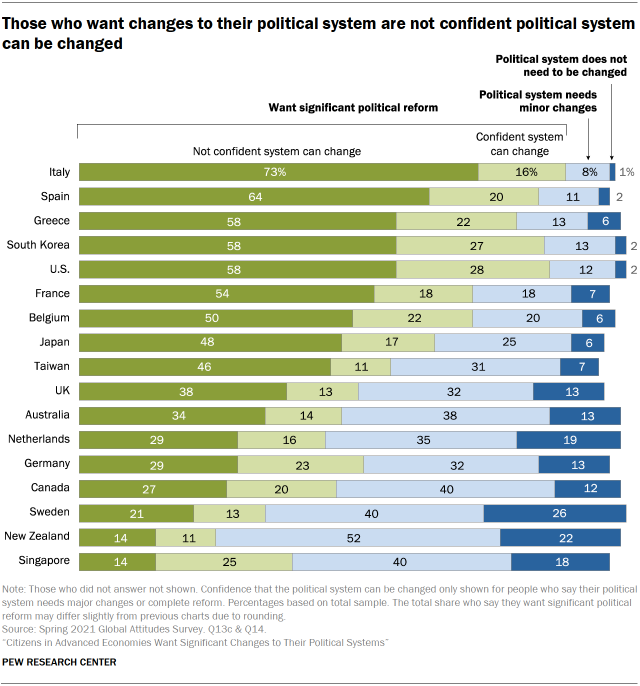

Many who want changes are not confident the political system can be effectively reformed

Respondents who said the political system where they live needs major changes or complete reform were then asked how confident they are that the system can be changed effectively. A median of 46% across the 17 publics express both a desire for change and a lack of confidence, while a median of just 18% are confident the change they feel their system needs can happen.

Italians are by far the most pessimistic: 73% want significant political reform but are not confident their system can be changed effectively. Roughly half or more share this view in Spain, Greece, South Korea, the U.S., France, Belgium and Japan. In every public except Singapore, larger shares of those who want political reform lack confidence that reform can happen effectively, compared with those who are confident change can occur.

Those who do not support the governing party are more likely to want political reform and lack confidence that the system can be changed effectively in nearly every public surveyed. In the UK, 47% of people who do not support the governing Conservative Party say their political system needs significant reform and do not think effective reform is possible, while only 17% of Conservative supporters hold this view.

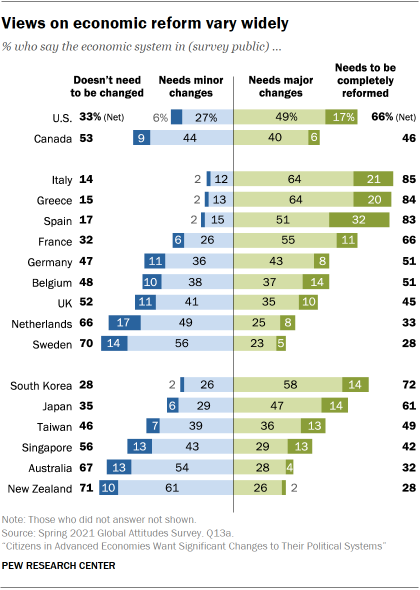

Views on economic system reform vary widely across 17 publics

When it comes to reforming the economic system, views are roughly split across the 17 publics surveyed. Majorities in seven publics say the economic system needs complete or major reform, while in five, majorities say the system needs minor changes or no reform at all, and elsewhere opinion is divided.

Calls for economic reform are highest in Italy, Greece and Spain – three countries where large shares say that the economic situation is not good. Additionally, large majorities in the U.S., France, South Korea and Japan believe the economic system in their countries needs significant reform. In the Netherlands, Sweden, Australia and New Zealand, where people generally describe their economic situation as good, large majorities say their economic system either does not need any changes or needs only minor changes.

Opinion on the degree to which the economic system needs reform is more balanced among Canadians, Germans, Belgians, Britons and Taiwanese.

In the U.S., 80% of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents think the economic system needs major changes or a complete overhaul, compared with 50% of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents who say the same.

There are also significant ideological differences on this question in the UK, Australia and Belgium, with respondents who place themselves on the ideological left voicing more support for economic reform than those on the right.

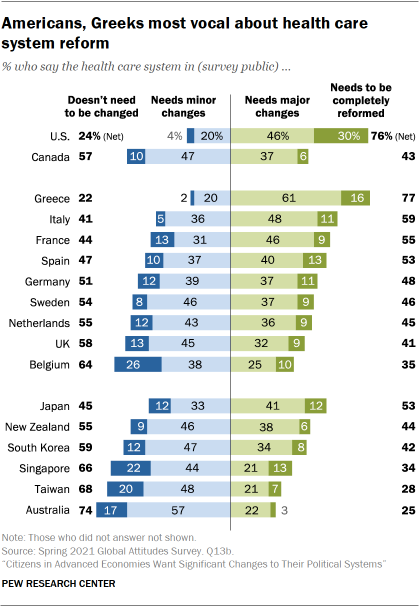

Publics mostly split on whether reform of health care system is needed

Overall, there is somewhat less support for reforming health care systems than for making significant reforms to political or economic systems. Still, roughly half or more in seven nations think the health care system needs major changes or needs to be completely reformed, and in the U.S. and Greece, roughly three-in-four express this view.

Majorities among supporters of both major American political parties believe the health care system needs at least major changes. Still, the desire for change is stronger among Democrats (39% want complete reform and 47% want major changes) than among Republicans (20% complete reform, 43% major changes).

Views are more positive elsewhere, especially in Belgium, Singapore and Taiwan, where one-in-five or more say their health care system doesn’t need to be changed.

Older people in Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Korea are more likely to say their health care system needs significant reform, while in the U.S., younger people are more likely to say this.

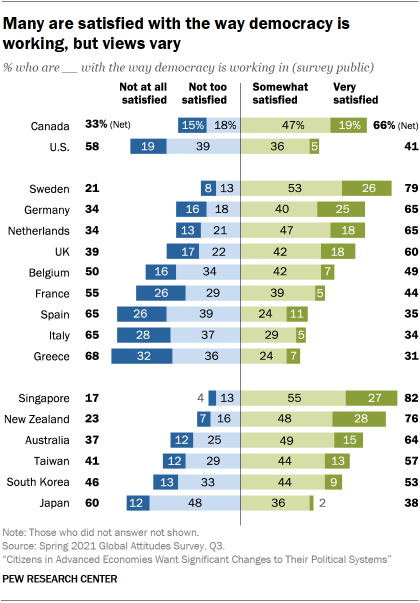

Wide range of views on how democracy is functioning

A median of 57% across 17 publics say they are satisfied with the way their democracy is working. But while views of democracy are relatively positive overall, assessments vary across the advanced economies surveyed.

Only 41% of Americans are satisfied with the way democracy is working in their country. (The survey was conducted in early February 2021, roughly a month after supporters of former President Donald Trump stormed the U.S. Capitol.)

In Europe, large majorities in Sweden and Germany are satisfied with the way their democracy is functioning, including roughly a quarter in each country who are very satisfied. Ratings are also positive in the Netherlands, where Prime Minister Mark Rutte won his fourth election as the survey was fielding.

On the other end of the spectrum, only around a third are content with their democracy in Spain, Italy and Greece. In these three countries, as well as France, at least a quarter say they are not at all satisfied with how their democracy is working.

Assessments of democracy are generally positive across most of the Asia-Pacific region. Satisfaction is particularly high in Singapore and New Zealand, where roughly a quarter are very satisfied. But more than half in Australia, Taiwan and South Korea also rate their democracies positively. Japan is an outlier in the region, with only 38% providing a positive assessment.

It is worth noting that previous Pew Research Center surveys have generally found more negative views of democratic functioning. This is due, in part, to discontent in many countries in Africa, Latin America and the Middle East, where the coronavirus has halted face-to-face data collection, meaning no recent comparative data on these attitudes are available.

In North America, Europe and the Asia-Pacific region, views of democracy have not changed much since the last time this question was asked in 2019, though slightly larger shares in Australia, Sweden and Greece are now satisfied. The UK is the only country where positive ratings have increased substantially since 2019, rising from 31% to 60%.

Across every public surveyed, people are much more likely to be satisfied with the way democracy is working if they support the party in power, say the current economic situation is good and think their society is more united now than it was before the coronavirus outbreak.

Most say their government respects people’s personal freedoms

The COVID-19 pandemic has raised concerns among many about the potential for governments to use the crisis to acquire more power over their citizens, at the expense of civil liberties. Among the advanced economies surveyed, though, half or more say their government respects the personal freedoms of its people. Still, sizable shares of the publics in many nations say their government does not respect such freedoms, including roughly four-in-ten or more in six countries. Respondents in the Asia-Pacific region say their government respects freedoms at slightly higher rates than those in European countries polled – a median of 73% versus just 62%, respectively.

Three-quarters of Canadians agree that their government respects individual liberties, while 63% of Americans hold this view.

Across Europe, people tend to say that their governments respect the personal freedoms of their people. In Sweden, 84% say their government respects personal freedoms, and roughly seven-in-ten agree in the Netherlands, Germany and the UK. Smaller majorities in Italy, Belgium, Spain and France say this, as well. In Greece, however, views are almost equally divided between those who think the government respects personal freedoms and those who think it does not.

Across the Asia-Pacific region, majorities say their government respects individual liberties. Roughly eight-in-ten in New Zealand say this, with roughly seven-in-ten or more saying the same of their government in Singapore, Taiwan and Australia. Two-thirds of Korean respondents also say their government respects freedoms, while roughly six-in-ten of Japanese say the same.

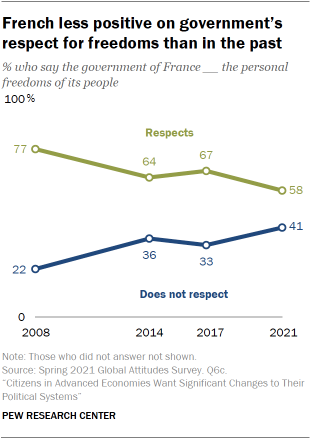

Over the last decade, the share saying their government does not respect personal freedoms has increased in France. When the question was first asked in 2008, just 22% of French adults said this about their government. In the time since, that share has nearly doubled, with 41% now agreeing that their government does not respect personal freedoms. Trend data on this question is not available in the other places surveyed.

In some countries, those with more education are more likely to say their government respects personal freedoms. For instance, in Germany, 83% of those with a postsecondary degree say this of the German government, while just 62% of those without a postsecondary degree agree. A similar difference prevails in Belgium (75% of those with a postsecondary degree vs. 54% of those without one). There are double-digit differences based on education on this subject in the U.S., Italy, Japan, Sweden, South Korea and Spain, as well.

Views on respect for freedoms also varies by income in some places. In South Korea, roughly three-quarters of those with higher incomes say their government respects freedoms, while just 60% of those with lower incomes agree. There is a similar split in Italy, where 68% of those with higher incomes and just 55% of lower-income adults say that the Italian government respects people’s individual liberties.

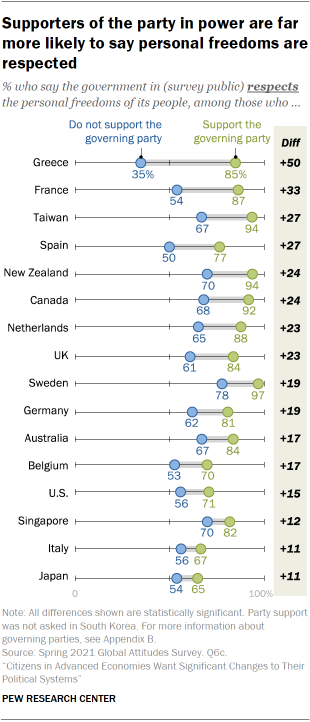

Those who support the party currently in power are far more likely to say their government respects freedoms than those who do not support the governing party in all the publics where this analysis is possible (party support was not asked in South Korea; for more on how governing party is defined, see Appendix B). The difference is largest in Greece: 85% of respondents who say they feel closest to New Democracy (ND) also attest that their government respects personal freedoms. Among those who do not feel closest to ND, just about a third say this. There are similar, sizable differences between supporters and non-supporters of En Marche in France, Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in Taiwan and the coalition between United Left, Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE) and Podemos in Spain.

In Europe, those with favorable views of some right-wing populist parties are less likely to say the government respects their people’s personal freedoms (for more on how populist parties are defined, see Appendix C). The largest gap in views is in Germany, where three-quarters of those with an unfavorable view of Alternative for Germany (AfD) say the German government respects individual liberties. In contrast, only four-in-ten of those with a favorable view of AfD perceive the government in this way. There are similar differences between those with favorable and unfavorable views of the Sweden Democrats, Forum for Democracy (FvD) and Party for Freedom (PVV) in the Netherlands, and Vox in Spain.

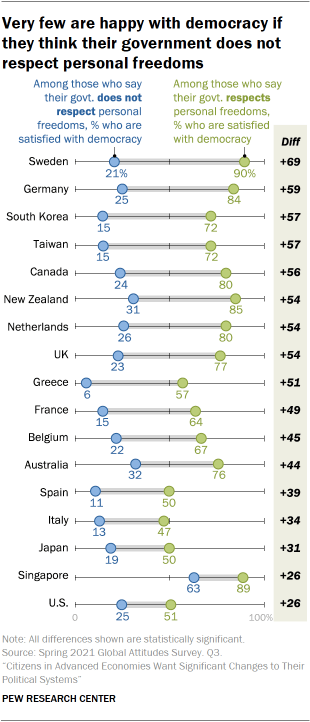

People are much more likely to rate their democracy positively if they think their government respects the personal freedoms of its people, compared with those who say their government does not respect freedoms.

In Sweden, for example, 90% of people who say their government respects personal freedoms are pleased with how democracy is working in their country. Among those who think the government does not respect the freedoms of its citizens, only 21% are satisfied. Similar differences of roughly 50 percentage points or more can be seen in nine other publics.