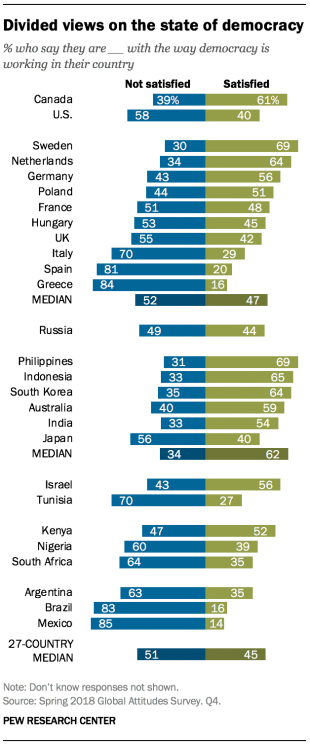

Around the world, more people are unhappy with the state of democracy in their countries than are content. Across 27 countries surveyed, a median of 51% are dissatisfied with the way their democracy is functioning, compared with 45% who are satisfied.

Discontent varies somewhat across regions of the globe. Those in the Asia-Pacific region, for example, tend to be satisfied with how democracy is working in their countries; only in Japan do a majority say they are dissatisfied.

Europeans are, on balance, disaffected; in six of the 10 European countries surveyed, half or more say they are dissatisfied with how democracy is working. Discontent is highest in the southern European countries of Italy, Spain and Greece, where 70% or more say they are dissatisfied. In contrast, roughly a third or fewer hold this view in Sweden and the Netherlands.

Across the sub-Saharan African and Latin American countries surveyed, around half or more in every country say they are dissatisfied with the way democracy is working.

Dissatisfaction with democracy is higher in emerging than advanced economies. A median of 60% express dissatisfaction across the nine emerging economies surveyed, compared with 50% across the 18 developed economies (for more on how advanced and emerging economies were classified, see Appendix C).

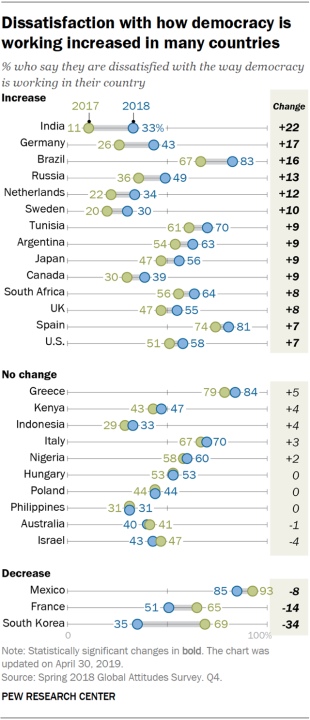

In many countries, dissatisfaction with democracy grew between 2017 and 2018

Between 2017 and 2018, dissatisfaction with the way democracy is working significantly increased in roughly half of the countries polled. This increasing dissatisfaction is evident around the globe, regardless of whether the economies are advanced or emerging.

Ten countries did not experience any significant changes in democratic dissatisfaction, while it decreased in only three countries: South Korea, France and Mexico. South Korean opinion has shifted the most since 2017 of any country surveyed, with the percentage saying they are dissatisfied dropping from 69% to 35%. Over this period, President Park Geun-hye was impeached and sentenced to 24 years in prison.

In the six countries where concerns about the economic situation significantly increased since 2017, democratic dissatisfaction also rose. For example, in India, concerns about the economy increased the most of any surveyed country – 12% thought the economy was in bad shape in 2017, but by 2018 this opinion was held by 30% of adults. This increase in economic discontent is coupled with a 22-point rise in democratic dissatisfaction. In Germany and Brazil, as well, the rising sense that the economy is not in good shape has been accompanied by double-digit shifts in democratic dissatisfaction.

In France and South Korea, the opposite relationship is found. Both countries experienced significant decreases in democratic dissatisfaction alongside improvements in economic outlook. The U.S. stands out as the only country in which dissatisfaction with democracy has increased at the same time that people think the country’s economic situation is improving.

Age, education and views of parties out of power sometimes associated with dissatisfaction

There are few consistent age-related patterns when it comes to who is dissatisfied with the performance of democracy in their country. While those ages 50 and older in Australia, the Netherlands, South Korea, the UK and Germany tend to be more dissatisfied with democracy than those ages 18 to 29, in other countries, there is no relationship between age and dissatisfaction.

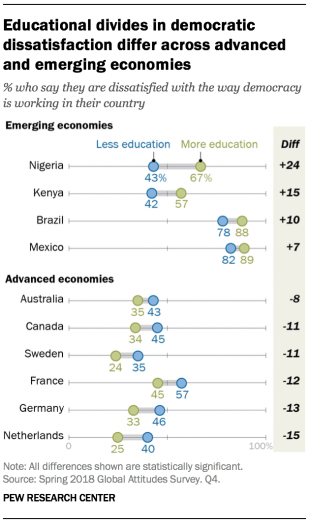

Education affects people’s satisfaction with democracy somewhat differently across emerging and advanced economies. In four of the nine emerging economies surveyed, those with higher levels of education tend to be more dissatisfied than those with lower levels of education.1 For example, Nigerians with at least a secondary degree are 24 percentage points more dissatisfied than those with less education.

The opposite is true in six of the 18 advanced economies surveyed, where those with lower levels of education are more dissatisfied than those with higher degrees. In the Netherlands, for example, those with less education are 15 points more dissatisfied than those with more education.

Income also impacts democratic dissatisfaction differently in some advanced and emerging economies. In four of the emerging economies surveyed, those with higher income levels are more dissatisfied than those with lower income levels.2 In contrast, in five of the advanced economies polled, those with lower incomes are more dissatisfied with democracy than those with higher incomes.

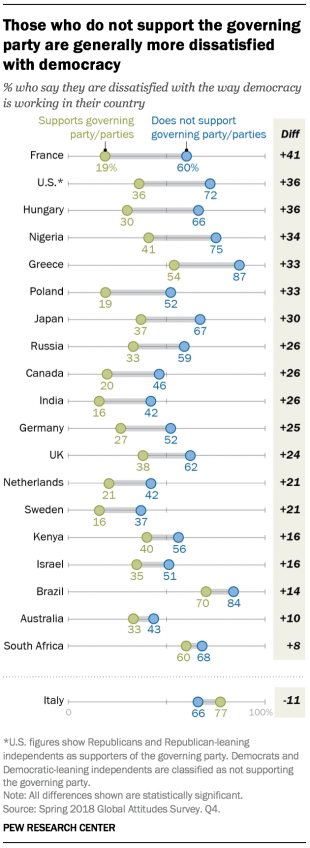

Across most of the countries surveyed, democratic dissatisfaction is higher among people who support parties that are not currently in government (see Appendix D). For example, in France, supporters of En Marche, the governing party, tend to be much less dissatisfied than people who don’t support En Marche. France boasts the largest gap in dissatisfaction between supporters and nonsupporters of the governing party (41 percentage points).

Italy, a country governed by a coalition of two populist parties, is an exception: 77% of those who support Northern League (now called League) or the Five Star Movement are dissatisfied, whereas 66% of those who do not support either party hold this view. (The coalition was created during the fieldwork period, nearly three months after the election.)

Dissatisfied democrats are more open to nondemocratic alternatives

This data, showing rising democratic dissatisfaction in many parts of the world, naturally elicits a question: If people are dissatisfied with democracy, are they more open to nondemocratic alternatives? To answer this question, we rely on data collected in 2017 from which we constructed an index of commitment to representative democracy.

Respondents in 2017 were asked whether each of a number of different systems would be a good or bad way to govern their country: (1) a democratic system where representatives elected by citizens decide on what becomes law (representative democracy); (2) a system in which experts, not elected officials, make decisions according to what they think is best for the country (rule by experts); (3) a system in which a strong leader can make decisions without interference from parliaments or courts (rule by a strong leader); and (4) a system in which the military rules the country (rule by the military).

They were then classified into three groups. “Committed democrats” are those who support a system where elected representatives govern, but do not support rule by experts, a strong leader or the military (i.e., nondemocratic governments). “Less-committed democrats” say a representative democracy is good, but support at least one nondemocratic form of government. “Non-democrats” are defined as those who do not support representative democracy and support at least one nondemocratic form of government. This commitment to democracy index ranges from 1 to 3, with 1 being the most committed to democracy and 3 being no commitment at all.

Respondents were also asked about their satisfaction with democracy, using the same question that we posed to them in 2018. All of the countries surveyed in 2018 were also surveyed in 2017. Across the 27 countries included in this report, people who were more dissatisfied with democracy also tended to be less committed to representative democracy, and so more likely to support governance options such as rule by experts, a strong leader or the military. This suggests that dissatisfaction with democracy is related to willingness to consider other, nondemocratic forms of government.