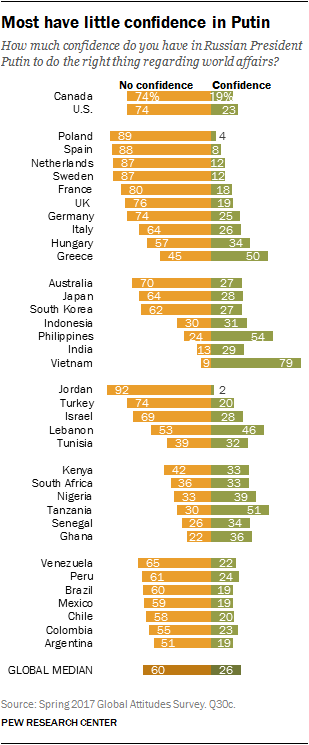

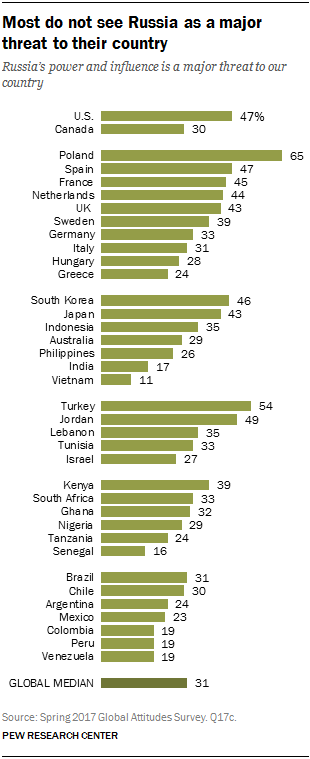

Around the world, few people trust Russian President Vladimir Putin to do the right thing when it comes to international affairs. A global median of roughly one-in-four (26%) say they have confidence in the Russian leader. Doubts about Putin’s handling of foreign policy, however, do not necessarily coincide with perceptions of Russia as a security risk. Across 37 countries, a median of 31% describe Russia’s power and influence as a major threat to their country – identical to the median percentage who say the same about China, and similar to the median share (35%) that sees America’s power and influence as a large threat.

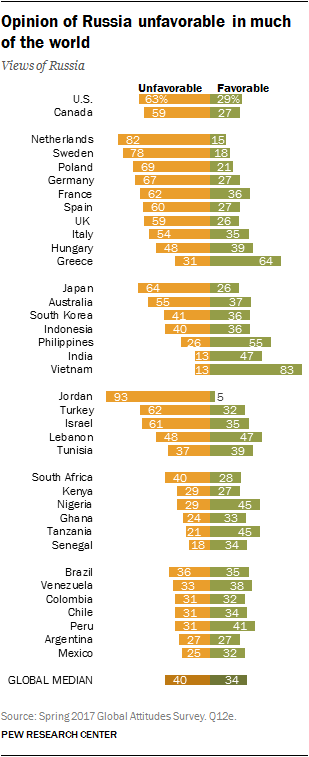

On balance, Russia’s international image is more negative than positive. Critical opinions of Russia are particularly widespread in the United States and Europe, while views are more mixed in the Asia-Pacific, the Middle East, sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America. In only three countries surveyed do majorities express a favorable opinion of Russia: Vietnam (83%), Greece (64%) and the Philippines (55%).

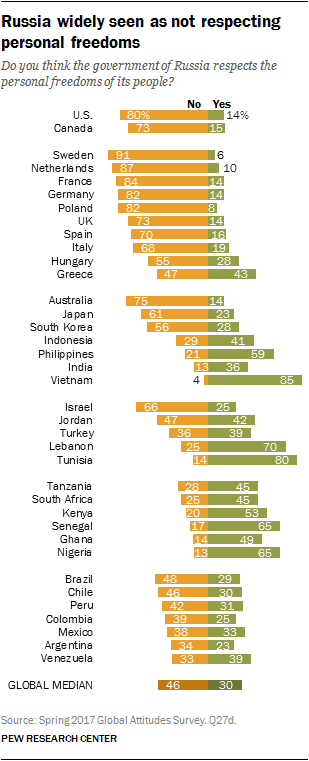

Many people doubt the Russian government’s commitment to civil liberties. Globally, a median of 30% say Russia respects the rights of its citizens, compared with 46% who disagree and 17% who do not offer an opinion. Skepticism about the protection of personal freedoms in Russia is widespread in the U.S. and Europe. Views are mixed across the Asia-Pacific, the Middle East and Latin America, while publics in sub-Saharan Africa are more convinced than not that the Russian government safeguards individual liberties at home.

These are among the major findings from a new Pew Research Center survey conducted among 40,951 respondents in 37 countries outside of Russia from Feb. 16 to May 8, 2017. (For views from within Russia, see “Russians Remain Confident in Putin’s Global Leadership.”)

Europeans are particularly harsh in their assessment of Putin, with a median in Europe of 78% expressing a lack of confidence in the leader. In the U.S. and Canada, few are confident in Putin’s global leadership, with more than three times as many people disliking Putin as liking him.

In a handful of nations (Vietnam, the Philippines, Tanzania and Greece), half or more are positive on Putin’s international performance. In other nations, many do not express any view of him: Roughly one-third or more in India, Indonesia, Ghana, Senegal, South Africa and Argentina do not share an opinion on the Russian leader.

Though Putin and Russia receive low ratings across much of the world, few see Russian power and influence as a major threat to their nation. Russia is seen as far less threatening than other issues such as the Islamic State militant group (ISIS) and climate change in every nation surveyed except for Poland and Jordan. A global median of 31% say that Russian power poses a major threat to their nation, compared with 62% for ISIS, 61% for climate change and 51% for cyberattacks from other countries and for the condition of the global economy. In fact, among the eight threats tested, Russia’s power and influence is tied with that of China for last place (median of 31%). (For views on global threats, see “Globally, People Point to ISIS and Climate Change as Leading Security Threats.”)

Generally, the Russian government is not seen as respecting the personal freedoms of its people. Across the 37 nations surveyed, a median of only 30% believe that Russia adheres to this tenet of democracy; that is lower than those who believe the same of France (60%, excluding France’s figures) and the U.S. (54%, excluding U.S. figures) but higher than for China (25%).

Both Americans (80%) and Canadians (73%) widely feel that Putin’s government does not respect personal freedoms. Similarly high shares feel this way in most European countries surveyed.

In the Middle East and the Asia-Pacific, views vary among the countries polled. Majorities in Tunisia, Lebanon, Vietnam and the Philippines think Russia respects civil liberties, while publics elsewhere in these regions are split on the issue.

Few have confidence in Putin on the international stage

In few countries surveyed do people exhibit confidence in Putin to do the right thing regarding world affairs. Globally, a median of 60% say they lack confidence in Putin’s global leadership.

Europe is the region least confident in Putin, with a median of 78% expressing a lack of confidence in the Russian president. Eight-in-ten or more in Poland (89%), Spain (88%), the Netherlands (87%), Sweden (87%) and France (80%) lack trust in Putin.

About half or more across the countries surveyed in Latin America also express doubts about Putin’s handling of foreign affairs. The same is true in the Middle East, with the exception of Tunisia, where views are more evenly divided (32% confident vs. 39% not confident).

Views of Putin are mixed in Africa, with sizable percentages not offering an opinion. Only in Tanzania do as many as half (51%) express confidence in the Russian leader’s international policies.

Putin also has the trust of half or more Vietnamese (79%), Filipinos (54%) and Greeks (50%).

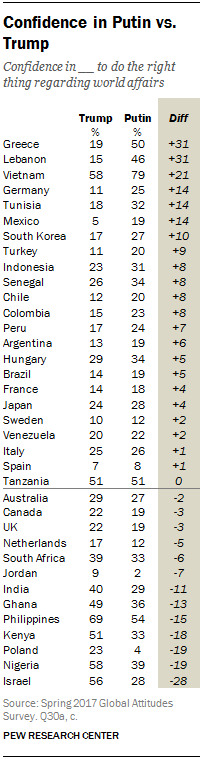

Although confidence in Putin’s handling of foreign affairs is generally low, in many countries he is more trusted than American President Donald Trump. Confidence in Putin most dramatically outpaces that in Trump in Greece and Lebanon (both +31 percentage points) and Vietnam (+21 points). On the other hand, confidence in Putin lags significantly behind confidence in Trump in Israel (-28 points), Nigeria and Poland (both -19 points) and Kenya (-18 points).

In terms of bilateral views, Americans are less confident in Putin than Russians are in Trump: Only 23% of the U.S. public has confidence in Putin on the world stage, whereas 53% of Russians have confidence in Trump. (Russia was surveyed during the same period as the other 37 countries, though its results are excluded elsewhere in this report.)

In a number of countries, gender matters when it comes to confidence in Putin. In 10 of the 37 countries polled, men express more confidence in Putin than do women.

Political ideology is also linked to views of Putin. In 11 of the 21 countries in which respondents were asked about ideology, those who place themselves on the right of the political spectrum are more confident in Putin. This is especially the case in Italy, where 39% of those on the right look favorably toward Putin compared with 24% on the left; in Greece (62% vs. 47%); and in Australia (33% vs. 19%).

In Venezuela, the trend is decidedly the opposite, with those on the left of the political spectrum being 28 points more likely to support Putin on the international stage. There is an 11-point gap in the same direction in Israel.

In the U.S., there is a partisan divide in views of Putin. Today, only 13% of Democrats express confidence in Putin, compared with about a third (34%) of Republicans. In 2015, there was almost no partisan gap: 20% of self-identified Democrats were confident in the Russian leader, compared with 17% of Republicans.

Russia not seen as particularly threatening in most countries

Compared with other global threats such as ISIS or climate change, most people around the globe express relatively muted concerns about Russia’s power and influence. Of the 37 nations polled, only in Poland and Jordan does Russia rank among the top three perceived threats to national security.

In the U.S., 47% view Russian power with great concern, though far more Americans view ISIS, cyberattacks and climate change with alarm. In Canada, only 30% view Russia’s power as a major threat, putting it among Canadians’ lowest-level concerns of the eight included in the survey.

Outside of Poland, most European publics express substantial but not overwhelming concern about their neighbor to the east. Greeks (24% major threat) and Hungarians (28%) are the least worried about Russia’s power and influence.

In the Middle East, only in Turkey do more than half (54%) see Russia as a threat to their country. Elsewhere in the region, concern is less widespread, with Israelis (27%) least worried. Across sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America, a third or fewer see Russia as very threatening. The exception is Kenya, where roughly four-in-ten (39%) express great concern about Russia’s power and influence.

In some instances, concerns about Russia vary by education level.1 In the U.S., for example, those with more education are slightly more likely to view Russia as a major threat than people with less education (51% vs. 44%). There is a wider education gap in the same direction in the Philippines (those with more education are 12 percentage points more likely to see Russia as a threat).

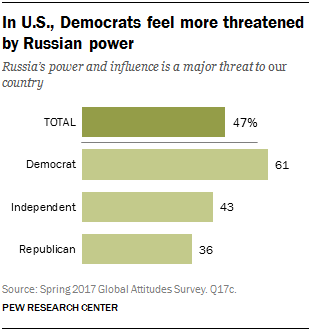

Especially in the United States, political leaning plays a role in views of Russia. Roughly six-in-ten Democrats (61%) view Russia as a major risk to national security, whereas only 36% of Republicans feel the same.

Russia viewed unfavorably in many countries

Opinions of Russia are more unfavorable than favorable in 19 of the 37 nations outside Russia that were surveyed. A median of just 34% view Russia in a positive light overall, while 40% view the country negatively. This reflects a slight improvement of Russia’s global image: In 2015, a global median of 51% viewed Russia negatively.

Regionally, Russia’s reputation is least favorable in Europe and North America. A full 63% of Americans and 59% of Canadians hold negative views of Russia. In Europe, a median of 61% feel the same, with anti-Russian sentiment particularly intense in the Netherlands (82%) and Sweden (78%).

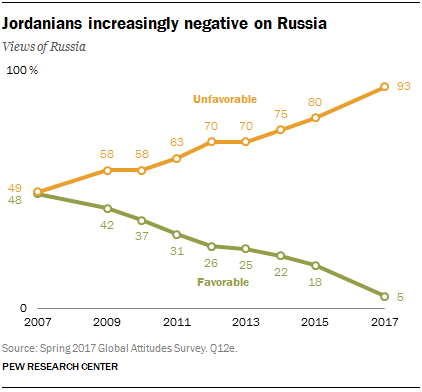

In the Middle East, majorities in Jordan (93%), Turkey (62%) and Israel (61%) hold negative views of Russia. Anti-Russian sentiment in Jordan has nearly doubled over the past decade – intensifying even before Russia’s involvement in the Syrian conflict.

Opinion is split in both Tunisia and Lebanon. Within Lebanon, views vary by religious sect: 83% of Shiites view Russia favorably, while only 21% of Sunnis and 38% of Christians feel the same.

Views of Russia are mixed in Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa, with many people undecided or not offering an opinion. Across the two regions, favorable views of Russia are most common in Nigeria (45% favorable), Tanzania (45%) and Peru (41%), while negative opinion is most pronounced in South Africa (40% unfavorable) and Brazil (36%).

Across all countries surveyed, Russia’s image is strongest in Vietnam, Greece and the Philippines; in all three countries, more than half the public holds a favorable view of Russia. In Greece, Russia’s favorability rating has stayed steady, hovering just above six-in-ten since Pew Research Center began measuring it in 2012; it currently stands at 64%.

In both the Philippines and Vietnam, sentiment toward Russia has improved over time. In Vietnam, 83% currently hold favorable views of Russia, an 8-point jump since 2015. And Filipinos, led by a president who appears to be shifting alliances away from the U.S. and toward Russia, are now significantly more favorable toward Russia (55%) than they were four years ago (35% in 2013).

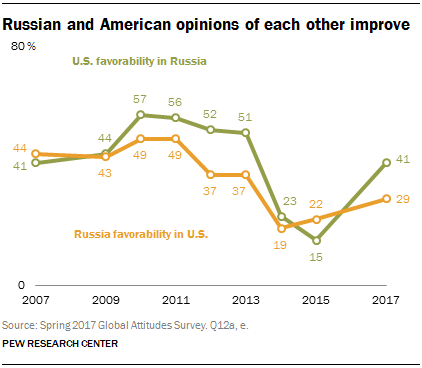

American and Russian views of one another have become less harsh since turning intensely negative in the wake of Russia’s annexation of Crimea and the imposition of Western sanctions on Russia. Today, roughly four-in-ten Russians (41%) feel favorably toward the United States, compared with just 15% in 2015. Views in the U.S. toward Russia have eased less: 22% of Americans felt favorably toward Russia in 2015, compared with 29% today.

In the U.S., partisan differences in attitudes toward Russia have emerged. In 2015, Democrats (71% unfavorable) and Republicans (73% unfavorable) held comparably negative views of Russia. In the past two years, Republican views have become significantly more positive, while Democratic views are little changed. Today, only 16% of Democrats have a favorable view of Russia, compared with 41% of Republicans.

(For more, see the June 26 report, “U.S. Image Suffers as Publics Around World Question Trump’s Leadership.”)

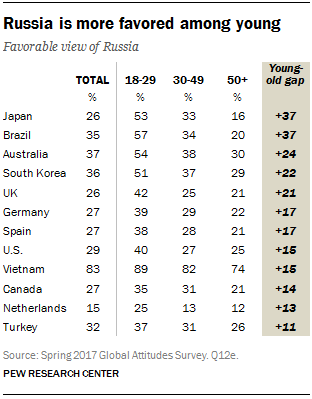

Across many nations, older people are significantly less likely to view Russia favorably than their younger counterparts – and in no nation are younger people significantly more critical of Russia than the older generation. In 12 nations, those ages 50 and older hold much more negative views of Russia than those 18 to 29. The generation gap is most notable in Japan and Brazil (both reveal a 37-point generational gap on favorability of Russia), Australia (24 points) and South Korea (22 points). In 11 other nations, anywhere from 40% to nearly 60% of those 50 and older offer no opinion on Russia.

Men also tend to favor Russia more than women: In seven nations, the share of men who feel warmly about Russia is anywhere from 7 to 17 points higher than the share of women who feel the same way. This gender gap is most pronounced in France (17-point gap) and Germany (14 points).

The relationship between education level and views of Russia varies by region. In France, the U.S. and Sweden, those with lower levels of education are significantly more likely to feel favorably toward Russia. However, in Tunisia and Turkey, those with higher levels of education are more likely to feel favorably toward Russia.

Many question Russia’s protection of personal freedoms

Globally, a median of 30% think the Russian government respects the personal freedom of its people. In North America, people in both the U.S. (80%) and Canada (73%) feel strongly that the Russian government does not respect civil liberties. In Europe, roughly eight-in-ten feel the same way in Sweden, the Netherlands, France, Poland and Germany. Greeks are the most likely to say Russia protects individual freedoms (43%).

Contrasting views on Russia’s respect for personal freedoms are found in both Asia and the Middle East. Majorities in Australia (75%), Japan (61%) and South Korea (56%) doubt the Russian government on this score, compared with most Vietnamese (85%) and Filipinos (59%) who think Russia is protecting civil liberties at home.

In the Middle East, Israel is the only country surveyed where a clear majority does not believe the Putin administration is protecting the rights of Russian citizens. In contrast, majorities in Tunisia (80%) and Lebanon (70%) give Russia favorable marks in this regard.

In sub-Saharan Africa, positive assessments of Russia’s record on civil liberties consistently outweigh negative views, especially in Nigeria and Senegal, where a 65% majority in each country says Putin’s government protects individual freedoms.

Across Latin America, publics tend to be divided on the issue. In Venezuela and Mexico, there is a 5- to 6-point difference in the share that thinks Russia respects freedoms and the share that thinks it doesn’t. In Argentina and Peru, the share that does not believe personal freedoms are respected in Russia is 11 points higher than the share that thinks they are. And in Brazil, Chile and Colombia, views are slightly stronger that Russia does not respect freedoms.

Across many countries surveyed, young people are more likely to believe that Russia respects the personal freedoms of its people. And nowhere is the oldest age group more likely to believe that Russia respects its people’s freedoms. In Japan, South Korea, Germany, the Netherlands, Australia, Chile and Spain, the gap between the youngest and oldest groups is 14 percentage points or more.