But majorities of both Republican and Democratic parents are satisfied with the quality of their children’s education

Pew Research Center conducted this study to better understand how parents with children in K-12 schools see their children’s education. This analysis is based on 3,251 U.S. parents with children in elementary, middle or high school. The data was collected as part of a larger survey of parents with children younger than 18 conducted Sept. 20 to Oct. 2, 2022. Most of the parents who took part are members of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This survey also included an oversample of Black, Hispanic and Asian parents from Ipsos’ KnowledgePanel, another probability-based online survey web panel recruited primarily through national, random sampling of residential addresses.

Address-based sampling ensures that nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology.

Most questions in this report were asked only of K-12 parents who indicated that their child attends a public, private or charter school (this excludes 197 parents who said their child is being homeschooled and 15 parents who didn’t provide an answer for the type of school their child attends).

Read more about the questions used for this report and the report’s methodology.

References to White, Black and Asian adults include only those who are not Hispanic and identify as only one race. Hispanics are of any race.

All references to party affiliation include those who lean toward that party. Republicans include those who identify as Republicans and those who say they lean toward the Republican Party. Democrats include those who identify as Democrats and those who say they lean toward the Democratic Party.

“Middle income” is defined here as two-thirds to double the median annual family income for panelists on the American Trends Panel. “Lower income” falls below that range; “upper income” falls above it. See the methodology for more details.

As the midterm election approaches, issues related to K-12 schools have become deeply polarized. Republican and Democratic parents of K-12 students have widely different views on what their children should learn at school about gender identity, slavery and other topics, according to a new Pew Research Center survey.

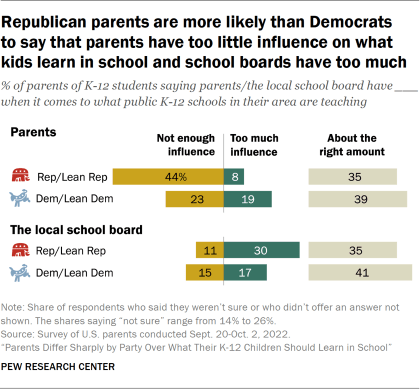

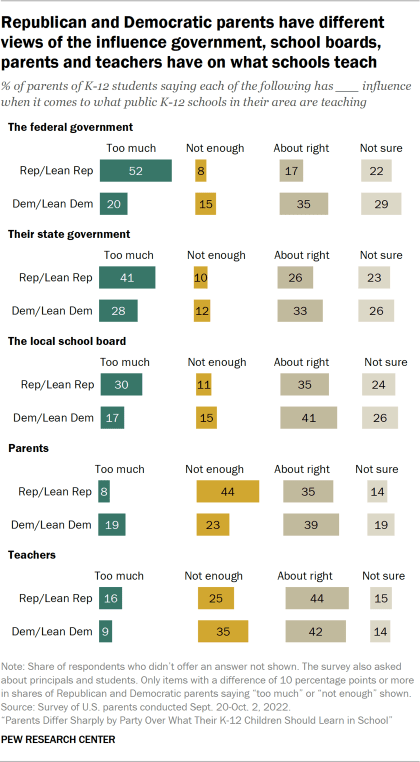

They also offer different assessments of the influence parents, local school boards and other key players have on what public K-12 schools in their area are teaching. Republican parents with children in K-12 schools are about twice as likely as Democratic parents to say parents don’t have enough influence (44% vs. 23%, including those who lean to each party). And Republicans are more likely than Democrats to say school boards have too much influence (30% vs. 17%). These parents also differ over the amount of input they personally have when it comes to what their own children are learning in school.

At the same time, Republican and Democratic parents – including those with children in public schools – are equally likely to say they are extremely or very satisfied with the quality of the education their children are receiving (58% each) and that the teachers and administrators at their children’s schools have values that are similar to their own (54% each).

Most of the questions in this report were asked only of parents of K-12 students who are not homeschooled. These questions relate to what parents want their children to learn in school, assessments of the quality of education their children are receiving and other aspects that relate to their children’s schools. Because parents with multiple children in K-12 schools may have different answers depending on the child or the school they attend, these parents were randomly assigned to think about their youngest or oldest child who is in grades K-12 when answering these questions. The data was weighted to account for each parent’s probability of being assigned to a child in elementary, middle or high school and is representative of all parents of students at each of these stages. Please see the report’s Methodology and Topline for details about the survey and how these questions were asked.

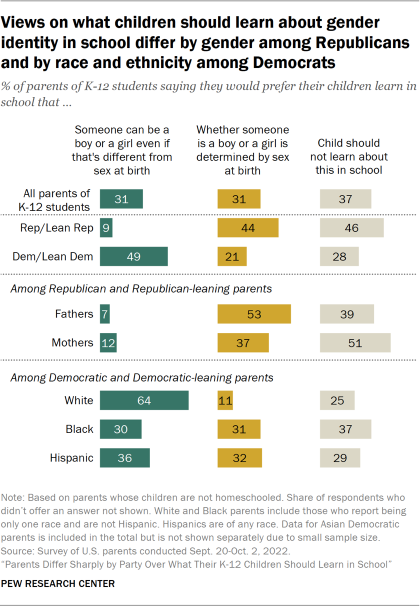

When it comes to what their children are learning in school, U.S. parents of K-12 students are divided over what they think their children should learn about gender identity: 31% say they would prefer that their children learn that whether someone is a boy or a girl is determined by the sex they were assigned at birth, and the same share say they’d rather their children learn that someone can be a boy or a girl even if that’s different from their sex at birth. A 37% plurality say their children shouldn’t learn about this in school.

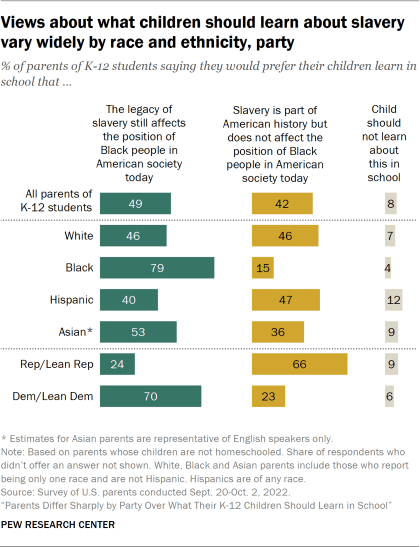

There is also no consensus when it comes to what parents want their children to learn about slavery: 49% say they would prefer that their children learn that the legacy of slavery still affects the position of Black people in American society today, while a smaller but sizable share (42%) would prefer that their children learn that slavery is part of American history but doesn’t affect the position of Black people in American society today.

On both gender identity and the legacy of slavery, there are differences ranging from 23 to 46 percentage points in what Republican and Democratic parents of K-12 students would prefer that their children learn in school. There are also large partisan differences when it comes to what parents want their K-12 children to learn about sex education and America’s standing in the world.

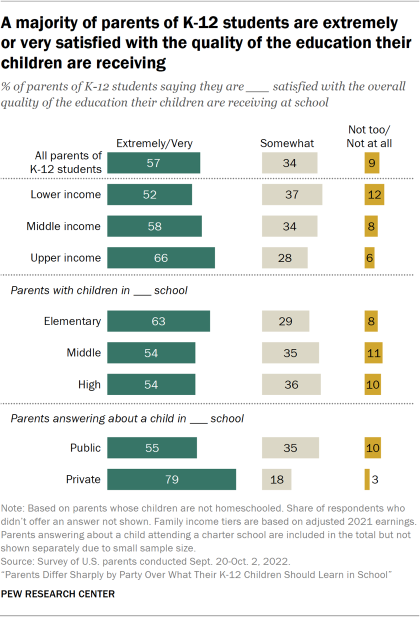

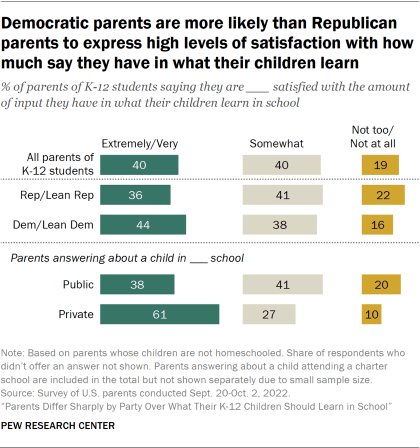

When asked to assess the quality of the education their children are receiving, a majority of U.S. parents of K-12 students (57%) say they are extremely or very satisfied. However, fewer than half (40%) express similar levels of satisfaction with the amount of input they have in what their children learn in school. Parents who are extremely or very satisfied with the amount of input they have express higher levels of satisfaction with the overall quality of their children’s education than those who are somewhat satisfied or who are not too or not at all satisfied with how much say they have in what their children learn in school.

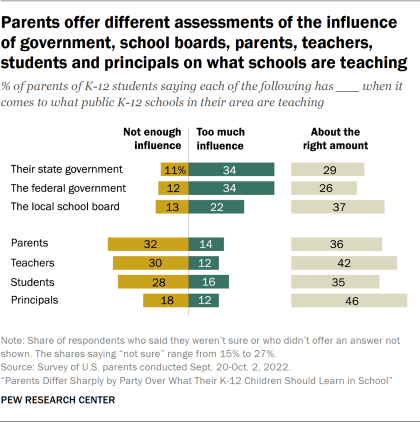

In addition to asking parents about how much influence parents and the school board have on what’s being taught in their local schools, parents were asked about the influence of the federal and state government, teachers, principals and students. While many parents say each of these has the right amount of influence or that they aren’t sure, larger shares say their state government, the federal government and their local school board have too much influence than say they don’t have enough influence. Conversely, more say parents, teachers, students and principals don’t have enough influence than say they have too much.

The nationally representative survey of 3,251 U.S. parents of K-12 students was conducted Sept. 20-Oct. 2, 2022, using the Center’s American Trends Panel.1 Among the other key findings:

Upper-income parents and parents answering about a child in private school express higher levels of satisfaction with the quality of their children’s education. About eight-in-ten parents answering about a student in a private K-12 school (79%) say they are extremely or very satisfied with the quality of the education their child is receiving, compared with 55% of those answering about a child in a public school.2 About two-thirds of upper-income parents (66%) express high levels of satisfaction, compared with 58% of those with middle incomes and a smaller share of those with lower incomes (52%).3 The difference between upper- and lower-income parents remains when looking only at those answering about a child in public school (the sample size for parents answering about private school children is too small to analyze separately).

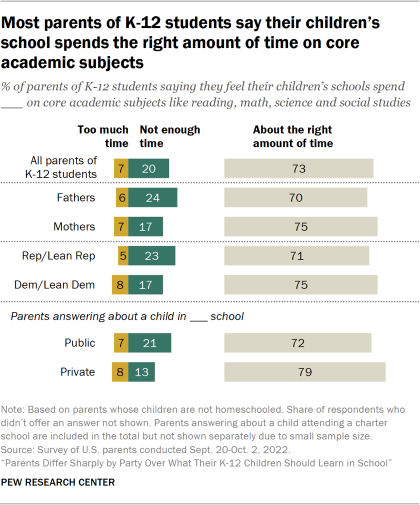

One-in-five parents of K-12 students say their children’s school doesn’t spend enough time on core academic subjects like reading, math, science and social studies. The shares saying this are higher among fathers (24%) than mothers (17%) and among Republican and Republican-leaning parents (23%) than those who identify with or lean toward the Democratic Party (17%). But majorities of 70% or more say their children’s school spends about the right amount of time on these subjects.

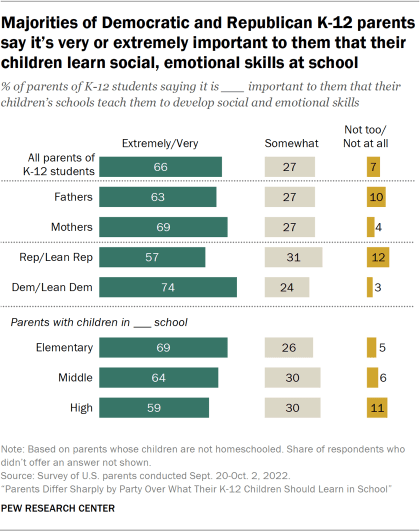

About two-thirds of parents say it is extremely or very important to them that their children’s school teaches them to develop social and emotional skills. Parents of elementary school students (69%) are more likely than parents of high school students (59%) to say it’s at least very important to them that their children’s school teaches these skills (64% of parents of middle schoolers say the same). And while majorities of Democratic and Republican parents say this is extremely or very important to them, this is a more common view among Democrats (74% vs. 57% of Republican parents).

Parents of K-12 students have mixed views about whether public school teachers should be allowed to lead students in prayer. About half of parents (52%) say this shouldn’t be allowed in any form, while 27% say leading students in Christian prayers should only be allowed if prayers from other religions are also offered and 19% say it should be allowed even if prayers from other religions are not offered. Among Democratic parents, 63% say public school teachers shouldn’t be allowed to lead students in any type of prayers; 39% of Republican parents say the same.

Elementary school parents express higher levels of satisfaction with the quality of their children’s education than those with older children

A majority of parents with children in K-12 schools (57%) say they are extremely or very satisfied with the overall quality of the education their children are receiving at school; another 34% are somewhat satisfied and 9% say they are not too or not at all satisfied. Parents of elementary school students (63%) are more likely than those with children in middle school or high school (54% each) to say they are extremely or very satisfied with the quality of their children’s education.

Parents’ assessments also vary widely depending on the type of school their children attend. About eight-in-ten parents answering about a child in private school (79%) express high levels of satisfaction with the quality of education their child is receiving, compared with a narrower majority (55%) of those answering about a child who is in public school.

Upper-income parents (66%) are more likely than those with middle (58%) and lower (52%) incomes to say they are extremely or very satisfied with the quality of their children’s education. While these differences in part reflect the fact that parents with higher incomes are more likely to have children in private schools, a larger share of upper-income parents (61%) than lower-income parents (51%) answering about a child in public school express a high level of satisfaction with the quality of the education their child is receiving.

Overall, Democratic and Democratic-leaning and Republican and Republican-leaning parents are equally likely to say they are extremely or very satisfied with the quality of the education their children are receiving at school (58% each). There is also no statistical difference between Republicans and Democrats when looking only at those answering about a child who attends a public school.

Four-in-ten parents of K-12 students are extremely or very satisfied with how much say they have in what their children learn in school

While a majority of parents of K-12 students express high levels of satisfaction with the quality of their children’s education, fewer than half (40%) say they are extremely or very satisfied with the amount of input they personally have in what their children learn in school; the same share (40%) are somewhat satisfied, and 19% say they are not too or not at all satisfied with the amount of input they have.

Parents answering about a child in private school are far more likely than those answering about a child in public school to say they are extremely or very satisfied with how much input they have in what their child learns in school (61% vs. 38%, respectively). One-in-five parents answering about a public school student say they are not too or not at all satisfied, compared with one-in-ten parents of those answering about a child in private school.

Partisanship also factors into these views: 44% of Democratic and Democratic-leaning parents say they are extremely or very satisfied with the amount of input they have in what their children learn in school, compared with 36% of parents who identify with or lean toward the GOP. This difference persists when looking only at Democratic and Republican parents answering about a child in public school.

One-in-five parents of K-12 students say their children’s school doesn’t spend enough time on core academic subjects

For the most part, parents of K-12 students think their children’s school spends about the right amount of time on core academic subjects like reading, math, science and social studies (73% say this). Still, one-in-five say their children’s school doesn’t spend enough time on these subjects, while 7% say too much time is spent on core academic subjects.

These views largely reflect the opinions of parents answering about a child in public school: 21% of these parents say their child’s school doesn’t spend enough time on core academic subjects, compared with 13% of parents answering about a child in private school (private school parents are more likely to say it’s about right).

Fathers (24%) and Republican parents (23%) are more likely than mothers (17%) and Democrats (17%) to say their children’s school doesn’t spend enough time on core academic subjects like reading, math, science and social studies, but seven-in-ten or more across these groups say their children’s school spends about the right amount of time on these subjects.

Most parents see value in their children learning social and emotional skills at school

About two-thirds of parents of K-12 students (66%) say it’s extremely or very important to them that their children’s school teaches them to develop social and emotional skills; another 27% say this is somewhat important and just 7% say it’s not too or not at all important.

Parents with children in elementary school (69%) are more likely than parents of high school students (59%) to say it’s extremely or very important for their children to learn social and emotional skills at school (64% of parents of middle schoolers say the same).

Majorities of mothers and fathers say it’s extremely or very important to them that their children’s schools teach them to develop social and emotional skills, but mothers are more likely to say this (69% vs. 63% of fathers). And while about three-quarters of Democratic and Democratic-leaning parents (74%) place high value on social-emotional learning, a smaller majority of Republicans and Republican leaners (57%) share this view.

No consensus among parents about what they want their children to learn about gender identity or slavery

The survey asked parents of K-12 students what they would prefer that their children learn in school about some issues that have been at the center of the national conversation about K-12 education. Parents are most divided when it comes to what their children should learn about gender identity, and there’s no majority consensus about what children should learn about slavery.

In turn, majorities of parents say they would prefer that their children learn that there are safe and effective methods of contraception (rather than being taught abstinence-only sex education) and that there are countries that are as good as or better than the United States (rather than learning that the U.S. stands above all other countries). On each of these, views differ along partisan lines.

Republican moms and dads have different views about what, if anything, schools should teach about gender identity; among Democrats, views differ by race and ethnicity

About three-in-ten parents of K-12 students (31%) say they would prefer that their children learn in school that whether someone is a boy or a girl is determined by the sex they were assigned at birth; an equal share (31%) say they would rather their children learn that someone can be a boy or a girl even if that’s different from their sex at birth. More – 37% – say their child shouldn’t learn about this at school. Parents of elementary school students (45%) are more likely than those with children in middle school or high school (31% each) to say their children shouldn’t learn about gender identity in school.

Views about what children should learn about gender identity in school vary considerably along party lines, although no position reaches a majority within either party. About half of Democratic and Democratic-leaning parents (49%) say they would prefer that their children learn that someone can be a boy or a girl even if that’s different from the sex they were assigned at birth; just 9% of Republican parents and those who lean to the GOP say the same. In turn, Republican parents (44%) are about twice as likely as Democratic parents (21%) to say they would prefer that their children learn that whether someone is a boy or a girl is determined by their sex at birth. Republican parents are also more likely than Democratic parents to say their children shouldn’t learn about this in school (46% vs. 28%).

Among Republicans, views differ by gender, with 53% of Republican fathers and 37% of Republican mothers saying they would prefer that their K-12 children learn that whether someone is a boy or a girl is determined by their sex at birth. Republican mothers are more likely than their male counterparts to say their children shouldn’t learn about this in school (51% vs. 39%).

There are no differences by gender among Democratic parents, but views among this group differ by race and ethnicity. A majority of White Democratic parents (64%) say they would prefer that their children learn that someone can be a boy or a girl even if that’s different from the sex they were assigned at birth, compared with 30% of Black and 36% of Hispanic Democratic parents.4

Black and Hispanic Democratic parents are more likely than their White counterparts to say they would prefer that their children learn that a person’s gender is determined by their sex at birth (31% and 32% vs. 11%, respectively). Black Democratic parents (37%) are more likely than those who are White or Hispanic (25% and 29%, respectively) to say their children shouldn’t learn about this in school.

Large shares of Black and Democratic parents would prefer that their children learn that the legacy of slavery still affects the position of Black people in American society today

About half of parents of K-12 students (49%) say they would prefer that their children learn that the legacy of slavery still affects the position of Black people in American society today. A smaller but substantial share (42%) would prefer that their children learn that slavery is part of American history but does not affect the position of Black people in American society today. Just 8% say their children shouldn’t learn about this in school.

Seven-in-ten Democratic parents, but only about a quarter of Republican parents (24%), say they’d prefer that their children learn in school that the legacy of slavery still affects the position of Black people in American society today. For their part, 66% of Republican parents would rather their children learn that slavery is part of American history but doesn’t affect the position of Black people today; just 23% of Democratic parents say the same.

Black parents (79%) are far more likely than Asian (53%), White (46%) and Hispanic (40%) parents to say they’d prefer that their children learn that the legacy of slavery has had a lasting effect. Among Democrats, however, White and Black parents are equally likely to say they want their children to learn this in school (81% each). A smaller share of Hispanic Democratic parents (48%) hold this view.

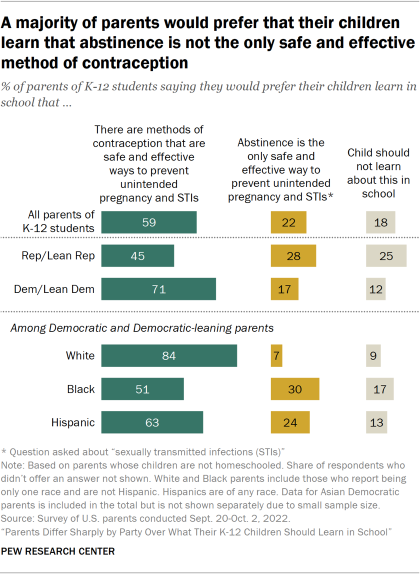

Most Democratic parents – and a plurality of Republican parents – would prefer that their children learn that there are safe and effective methods of contraception

About six-in-ten parents of K-12 students (59%) say they would prefer that their children learn that there are methods of contraception that are safe and effective ways to prevent unintended pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections (STIs); 22% would rather their children learn that abstaining from sex is the only safe and effective method to prevent unintended pregnancy and STIs, and 18% say their children shouldn’t learn about this in school (parents of elementary school children are the most likely to say this).

A large share of Democratic parents (71%) say they would like their children to learn in school that there are safe and effective methods of contraception, while 17% would prefer their children to learn that abstinence is the only safe and effective way to prevent unintended pregnancy and STIs and 12% don’t think their children should learn about this in school.

Views are more divided among Republican parents, but a plurality (45%) say they would prefer that their children learn that there are methods of contraception that are safe and effective; 28% would rather their children learn abstinence is the only safe and effective way, and a quarter say their children shouldn’t learn about this in school.

Among Democrats, White parents (84%) are far more likely than Hispanic (63%) and Black (51%) parents to say they would prefer that their children learn that there are methods of contraception that are safe and effective in preventing unintended pregnancy and STIs. Still, majorities or pluralities across these groups say this. Only 7% of White Democratic parents would prefer that their children learn that abstinence is the only effective way, compared with 30% of Black Democratic parents and 24% of those who are Hispanic.

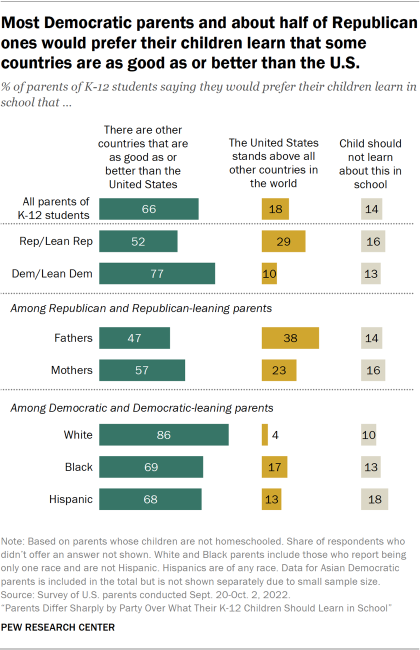

Fathers and Republican parents are more likely than mothers and Democrats to say they want their children to learn that the U.S. stands above all other countries in the world

About two-thirds of parents of K-12 students (66%) say they would prefer that their children’s school teach them that there are other countries in the world that are as good as or better than the United States; 18% would rather their children learn that the U.S. stands above all other countries in the world, and 14% don’t think their children should learn about this in school.

Views on this differ widely by party, with 77% of Democratic parents saying they would prefer that their children learn that there are other countries that are as good as or better than the U.S., compared with 52% of Republican parents.

And while fewer than half of Republican and Democratic parents say they would prefer that their children learn that the U.S. stands above all other countries in the world, Republicans (29%) are more likely than Democrats (10%) to hold this view.

A larger share of fathers (24%) than mothers (13%) say they’d prefer that their children learn that the U.S. stands above all other countries, and this difference is particularly pronounced among Republicans. About four-in-ten Republican dads (38%) say this, compared with 23% of Republican moms. In turn, a majority of Republican moms say they would prefer that their children learn that there are other countries that are as good as or better than the U.S. (57% vs. 47% of Republican dads).

Among Democrats, Black (17%) and Hispanic (13%) parents are more likely than White parents (4%) to say they would prefer that their children learn that the U.S. stands above all other countries. But most White (86%), Black (69%) and Hispanic (68%) Democratic parents say they would prefer that their children learn that there are other countries that are as good as or better than the U.S.

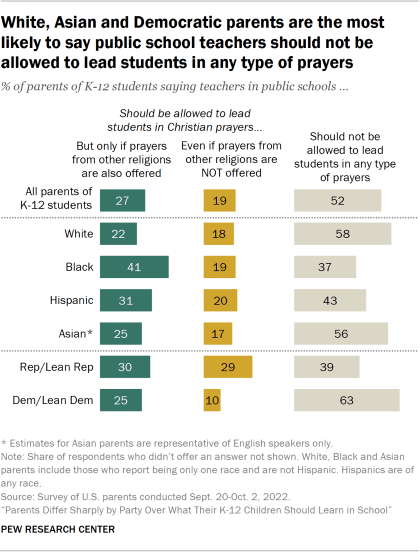

Views about whether public school teachers should be allowed to lead students in prayer are somewhat mixed

About half of parents of K-12 students (52%) say public school teachers shouldn’t be allowed to lead students in any type of prayers, but more than four-in-ten say public school teachers should be allowed to lead students in Christian prayers, including 27% who say this should be allowed only if prayers from other religions are also offered and 19% who say this should be allowed even if prayers from other religions are not offered.

Similar shares of parents across racial and ethnic groups (between 17% and 20%) say public school teachers should be allowed to lead students in Christian prayers even if prayers from other religions are not offered. But Black parents are the most likely to say teachers should be allowed to lead students in Christian prayers as long as prayers from other religions are also offered (41% vs. 31% of Hispanic parents, 25% of Asian parents and 22% of White parents). Some 37% of Black parents and 43% of Hispanic parents say public school teachers shouldn’t be allowed to lead students in any type of prayers, smaller than the share of White (58%) and Asian (56%) parents who say the same.

Most Democratic parents (63%) say public school teachers shouldn’t be allowed to lead students in any type of prayers, compared with 39% of Republican parents. Among Republican parents, 30% say teachers should be allowed to lead students in Christian prayers, but only if prayers from other religions are also offered (25% of Democrats agree), and 29% say teachers should be allowed to lead students in Christian prayers even if prayers from other religions are not offered (vs. 10% of Democratic parents).

Perhaps not surprisingly, these views vary considerably by religious affiliation. About four-in-ten White evangelical parents (41%) say public school teachers should be allowed to lead students in Christian prayers, even if prayers from other religions are not offered. A quarter (25%) of Black Protestant parents share this view, as do 19% of Catholic, 16% of White non-evangelical Protestant and 7% of unaffiliated parents.

Religiously unaffiliated parents are by far the most likely to say public school teachers shouldn’t be allowed to lead students in any type of prayers: 73% say this, compared with 55% of White non-evangelical parents, 45% of Catholic parents, 31% of Black Protestant parents and 28% of White evangelical parents.

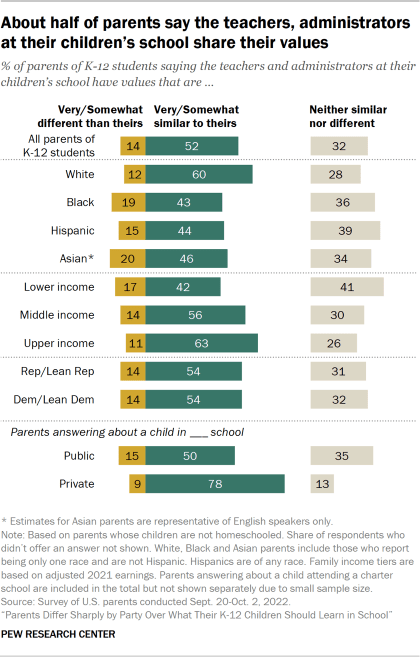

White parents are more likely than other major racial or ethnic groups to say teachers and administrators share their values

About half of parents of K-12 students (52%) say the teachers and administrators at their children’s school have values that are at least somewhat similar to their own, with a relatively small share (14%) saying these teachers and administrators have values that are very similar to theirs. About a third of parents (32%) say the values of the teachers and administrators at their children’s school are neither similar nor different, and 14% say they are very or somewhat different than their own values.

These views vary considerably by the type of school students attend. Some 46% of parents answering about a child in private school say the teachers and administrators at their child’s school have values that are very similar to their own, compared with 11% of those answering about a child in public school (78% of those answering about a child in private school say the values are at least somewhat similar vs. 50% of those answering about a child in public school).

White parents are the most likely to say the teachers and administrators at their children’s school have values that are at least somewhat similar to their own. Six-in-ten White parents say this, compared with 46% of Asian parents, 44% of Hispanic parents and 43% of Black parents. These differences remain when looking only at parents answering about a child in public school.

Majorities of parents with upper (63%) and middle (56%) incomes say the teachers and administrators at their children’s school have values that are at least somewhat similar to their own, compared with 42% of those with lower incomes. These income differences remain when looking only at parents answering about a child who attends public school.

Republican and Democratic parents – including those answering about a child in a public K-12 school – are about equally likely to say the teachers and administrators at their children’s school have values that are very similar (10% and 12%, respectively) or somewhat similar (39% and 40%) to their own.

Overall, parents who are less satisfied with the amount of input they have into what their children are learning at school are more likely to say the teachers and administrators at their children’s school don’t share their values: 29% of parents who say they are not too or not at all satisfied with how much input they have say this, compared with 11% of those who are extremely or very satisfied. Among those who express high levels of satisfaction with the amount of input they have, 63% say the teachers and administrators at their children’s school share their values (vs. 31% of those who are not too or not at all satisfied).

Wide partisan gaps in views of how much influence parents, school boards and governments have on what public K-12 schools teach

In addition to asking parents of K-12 students about their assessments of and experiences with their children’s education, the survey also asked more generally about their views of how much influence each of the following have on what public K-12 schools in their area are teaching: the federal government, their state government, the local school board, parents, teachers, principals and students.

For the most part, parents of K-12 students either say that each of these actors has the right amount of influence or that they are not sure. But to the extent that parents see each of these as having too much or not enough influence on what public K-12 schools in their area are teaching, more say the local school board, their state government and the federal government have too much influence than say they don’t have enough influence. In turn, larger shares say parents, teachers, principals and students don’t have enough influence than say they have too much influence.

Republican parents (44%) are far more likely than Democratic parents (23%) to say parents in general don’t have enough influence when it comes to what public K-12 schools in their area are teaching. And by double-digit margins, Republican parents are more likely than their Democratic counterparts to say the federal government (52% of Republicans vs. 20% of Democrats), their state government (41% vs. 28%) and their local school board (30% vs. 17%) have too much influence.

When it comes to how much influence they think teachers have on what public K-12 schools are teaching, Republican and Democratic parents alike are more likely to say teachers don’t have enough influence than to say they have too much influence. But Democratic parents are more likely than Republican parents to say teachers don’t have enough influence (35% vs. 25%, respectively). And while 16% of Republican parents say teachers have too much influence, a smaller share of Democratic parents (9%) say the same.