While majorities of Americans express support for paid leave for both mothers and fathers following the birth or adoption of a child, the survey suggests that the public sees different roles for men and women when it comes to caring for children or for other family members. Moreover, many Americans say men face more pressure than women from society and from employers to focus on their job or career.

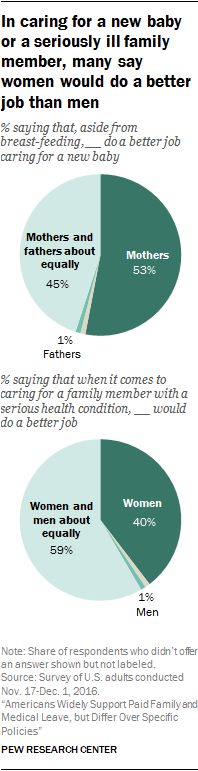

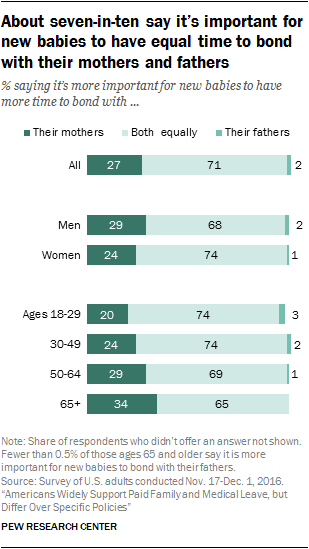

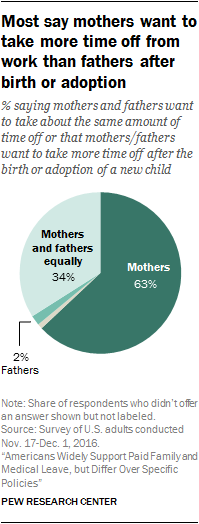

In a series of questions aimed at exploring the roles of mothers and fathers with new babies, the survey finds that a majority (71%) think it’s important for a new baby to have equal time to bond with their mother and their father. Yet a somewhat larger share of Americans think that, aside from breast-feeding, mothers would do a better job caring for a new baby than say both mothers and fathers would do about an equally good job (53% vs. 45%); only 1% say fathers would do a better job than mothers. In addition, most (63%) say mothers generally want to take more time off from work than fathers do after the birth or adoption of their child.

When it comes to caring for a family member with a serious health condition, a majority (59%) say men and women would do about an equally good job, but a substantial share (40%) say women would generally do a better job than men (just 1% say men would do a better job than women).

Many Americans (45%) also say that, in general, caregiving responsibilities when a family member is seriously ill fall mainly on women, but the perceptions of men and women differ widely: 59% of women say caregiving responsibilities fall mainly on their own gender, compared with 29% of men who say these responsibilities fall mainly on women. About seven-in-ten men (69%) – and 40% of women – say caregiving responsibilities fall equally on men and women.

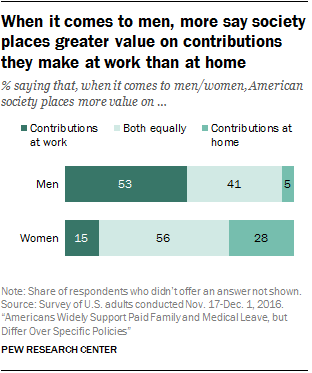

About half say American society values the contributions men make at work more than the contributions they make at home

Asked what American society values more these days when it comes to men, about half (53%) of all adults point to the contributions men make at work, while just 5% say society values the contributions men make at home more and 41% say society values both equally. In contrast, a majority (56%) of Americans say that, when it comes to women, society values the contributions they make at work and at home equally. Still, more say society places greater value on the contributions women make at home (28%) than say society values the contributions women make at work more (15%).

For the most part, assessments of what American society values more when it comes to both men and women do not vary substantively across demographic groups. However, Americans with at least a bachelor’s degree are far more likely than those with less education to say society places greater value on the contributions men make at work; two-thirds among the more highly educated say this, compared with about half (51%) of those with some college and 43% of those with a high school diploma or less education.

In turn, about half (49%) of those with a high school diploma or less and 42% of those with some college education say society places equal value on the contributions men make at work and at home, while just 29% of those with a college degree or more share this view. A similar pattern is evident when looking at income. Those with higher household incomes are more likely than those with lower incomes to point to the contributions men make at work as being more valued, and those with lower incomes are more likely to say society values the contributions men make at work and at home about equally.

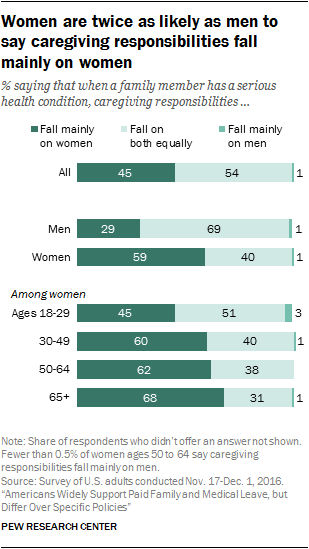

Men and women disagree on who has more caregiving responsibilities

A narrow majority (54%) of Americans say that, in general, when a family member has a serious health condition, caregiving responsibilities fall on both women and men equally. Still, more than four-in-ten (45%) say caregiving responsibilities fall mainly on women, while virtually no one (1%) says they fall mainly on men.

Women are about twice as likely as men to say caregiving responsibilities fall mainly on women when a family member has a serious health condition (59% vs. 29%), while men tend to say responsibilities fall on both equally. About seven-in-ten men say this (69%), compared with 40% of women.

Among women, the view that family caregiving responsibilities fall mainly on women is particularly common among those ages 30 or older. While young women ages 18 to 29 are about evenly divided between those who say caregiving responsibilities fall mainly on their gender (45%) and those who say they fall equally on women and men (51%), majorities of women ages 30 to 49 (60%), 50 to 64 (62%), and 65 and older (68%) say these responsibilities fall mainly on women. There are no similar divisions among men in different age groups.

When asked whether women or men would do a better job caring for a family member with a serious health condition, a majority (59%) of Americans say both would do about an equally good job, while 40% say women would do a better job than men and just 1% say men would do a better job. Larger shares of women than men say women would do a better job caring for a family member with a serious health condition (45% vs. 34%), but more women say both would do an equally good job than say their own gender would (54% of women say both equally).

The view that women would be better caregivers than men is shared more widely among older Americans. Some 46% of those ages 50 to 64 and an even higher share (56%) among those 65 and older say women would do a better job than men when it comes to caring for a seriously ill family member, compared with about three-in-ten adults ages 18 to 29 (31%) and 30 to 49 (30%). Older women are particularly likely to say their own gender would be better at providing care for a family member with a serious health condition: 63% of women ages 65 and older say this is the case, compared with 48% of their male counterparts and 50% of women ages 50 to 64, 37% of women 30 to 49, and a third of adult women younger than 30.

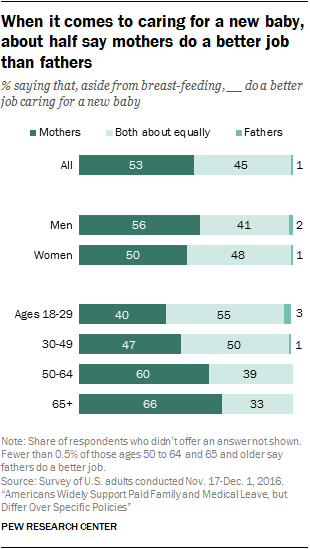

Many say mothers do a better job caring for a new baby than fathers, but about seven-in-ten say it’s equally important for babies to bond with both

While more Americans say men and women would be equally good at providing care for a family member with a serious health condition than say women would be better caregivers, the balance of opinion on who does a better job caring for a new baby tilts the other way: 53% of Americans say that, aside from breast-feeding, mothers generally do a better job caring for a new baby than fathers, while 45% say both do about an equally good job.

The view that mothers do a better job than fathers caring for a new baby is more common among men than women (56% vs. 50%, respectively) and among those ages 50 and older. Six-in-ten Americans ages 50 to 64 and about two-thirds (66%) of those 65 and older say mothers do a better job than fathers, compared with 47% of those ages 30 to 49 and 40% of adults younger than 30.

Young women are more likely than men or women in any age group to have a more gender-balanced view of the job mothers and fathers do caring for a new baby. About six-in-ten adult women younger than 30 (62%) say both mothers and fathers do about an equally good job, while about a third (34%) say mothers are better caregivers; men in the same age group are evenly divided between those who say mothers and fathers do an equally good job and those who say mothers do a better job (47% each).

Across political lines, Republicans who describe their views as conservative stand out. About two-thirds (64%) in this group say mothers do a better job than fathers caring for a new baby, while 34% say both mothers and fathers do about an equally good job. Among Republicans who say their views are liberal or moderate, as well as among conservative or moderate Democrats and liberal Democrats, opinions are more evenly divided between those who say mothers are better caregivers for new babies and those who say mothers and fathers are equally good.

Still, a majority (71%) of Americans say it’s equally important for new babies to have as much time to bond with their fathers as with their mothers. This is particularly the case among those who say both mothers and fathers do an equally good job caring for a new baby – 89% of this group says it’s equally important for babies to bond with mothers and fathers. Even so, a majority (58%) of those who say mothers are better caregivers also say it’s important for babies to bond with both equally.3

Majorities across demographic and partisan groups say it’s important for new babies to have equal time to bond with their mothers and their fathers, but women are somewhat more likely to say this is the case (74% vs. 68% of men), as are adults younger than 50 (74% vs. 68% of those ages 50 and older). And while about three-quarters of liberal (74%) and moderate or conservative (73%) Democrats as well as moderate or liberal Republicans (73%) say it’s important for new babies to have equal time to bond with mothers and fathers, six-in-ten Republicans who describe themselves as conservative share this view.

Men and women agree mothers want to take more time off than fathers

A majority of Americans – including 66% of women and 61% of men – think mothers generally want to take more time off from work than fathers following the birth or adoption of a new child. But views on who wants to take more time off vary considerably across age groups. About eight-in-ten adults ages 65 and older (78%) say mothers generally want to be home longer with a new child than fathers, as do seven-in-ten adults ages 50 to 64 and a narrower majority (59%) of those 30 to 49. In contrast, adults ages 18 to 29 are evenly divided: 47% say mothers want to take more time off than fathers, and the same share says both mothers and fathers generally want to take about the same amount of time off from work when they have a new child.

Household income is also related to opinions about who wants to stay home longer when a new child arrives. About two-thirds of those with annual household incomes between $30,000 and $74,999 (66%) and those with incomes of $75,000 or higher (68%) say mothers generally want to take more time off from work than fathers. Among those with incomes below $30,000, however, about the same shares say mothers want to take more time off as say mothers and fathers generally want to take about the same amount of time off from work after the birth or adoption of a new child (49% and 47%, respectively).

Majorities across party lines say mothers generally want to take more time off from work than fathers, but this is particularly the case among Republicans: 75% of Republicans say this, compared with about six-in-ten Democrats (59%) and independents (61%).

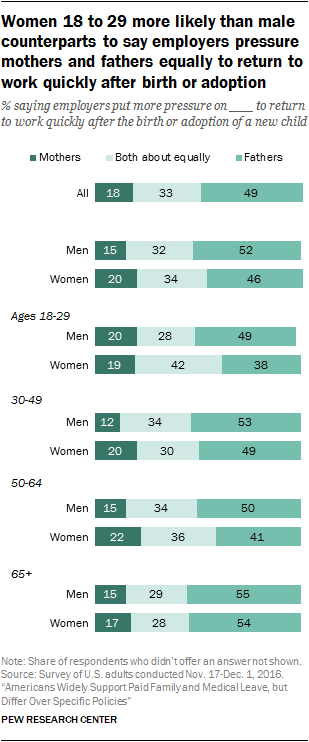

Larger share of the public says fathers, rather than mothers, are pressured to return to work quickly after the arrival of a child

About half of adults say employers put greater pressure on fathers than mothers (49%) to return to work quickly after the birth or adoption of a new child. This is significantly higher than the share saying mothers face more pressure than fathers (18%) or that both face about the same amount of pressure (33%) from employers. Views on this question vary slightly by gender, with men and women each more likely than the other to say their own gender faces more pressure from employers to return to work quickly (20% of women and 15% of men say mothers face more pressure; 52% of men and 46% of women say fathers do). About a third of each group say employers put about the same amount of pressure on mothers and fathers.

Gender differences are more pronounced among adults ages 18 to 29; about four-in-ten women in this age group (42%) say employers put about the same amount of pressure on fathers and mothers to return to work quickly after welcoming a new child, while 28% of young men share this view. In turn, about half (49%) of adult men younger than 30 say fathers face more pressure than mothers, compared with 38% of women in this age group who say the same. About one-in-five young men (20%) and women (19%) say employers put more pressure on mothers than on fathers.

Among adults ages 30 to 49 and those 50 to 64, similar shares of men and women say employers put about the same amount of pressure on both mothers and fathers, but somewhat higher shares of women than men say mothers face more pressure (20% vs. 12%, respectively, among those ages 30 to 49 and 22% vs. 15% among those 50 to 64). And while half of men ages 50 to 64 say employers put more pressure on fathers, 41% of women in this age group say this is the case.

Differences also emerge across education and income lines. For example, about half of those with household incomes of $75,000 or more (53%) and those with incomes between $30,000 and $74,999 (49%) say employers generally put more pressure on fathers than on mothers to return to work quickly after the birth or adoption of a new child. Among those with household incomes under $30,000, however, opinions are more evenly divided, with about as many saying there is more pressure on fathers (39%) as say fathers and mothers face about the same amount of pressure (42%). Similarly, 56% of adults with a bachelor’s degree or higher say employers put more pressure on fathers to return to work quickly, compared with 48% of those with some college and 43% of those with a high school diploma or less education.

A plurality says it’s ideal for young children to have a stay-at-home parent

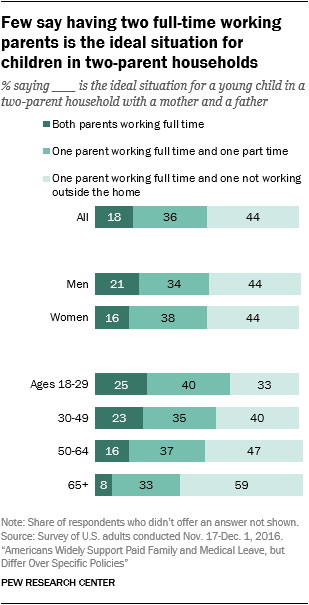

Most two-parent households today include two parents who work at least part time. Still, a 44% plurality of Americans say the ideal situation for a young child in a household with both a mother and a father is for one parent to work full time and one parent to not work outside the home; 36% say the ideal situation for young children is to have one parent working full time and one working part time, while about one-in-five (18%) say having both parents working full time is ideal.

Opinions about the ideal situation for children with a mother and a father vary considerably across age groups, with adults ages 65 and older particularly inclined to say young children are better off with an at-home parent: About six-in-ten adults in this age group (59%) say this is the ideal situation, compared with about half (47%) of those ages 50 to 64 and even smaller shares of those 30 to 49 (40%) and those younger than 30 (33%). Still, among the two younger groups, more say the ideal situation for young children is to have one parent working full time and one part time than say it’s better for children when both parents work full time (40% vs. 25% among those ages 18 to 29 and 35% vs. 23% among those 30 to 49).

Republicans who describe their views as conservative are far more likely than Americans with other partisan or ideological orientations to prefer a situation for young children where one parent works full time and one parent does not work outside the home: Six-in-ten conservative Republicans say this is the ideal situation, compared with 45% of moderate or liberal Republicans, 37% of moderate or conservative Democrats and 32% of liberal Democrats. Only about a quarter or fewer among each group say it’s ideal for young children in two-parent households to have two full-time working parents.

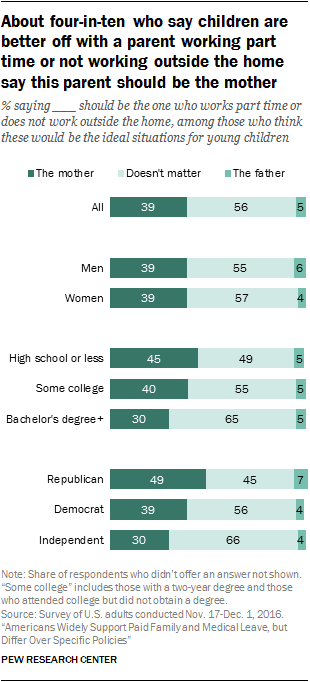

For the most part, Americans who say the ideal situation for young children in a two-parent household with a mother and a father is for one parent to work full time and the other parent to work part time or to not work outside the home say it doesn’t matter which parent works part time or stays home (56% say this). Still, about four-in-ten (39%) say the mother should be the one who works part time or doesn’t work outside the home, while just 5% point to the father.

Here, too, political orientation is a factor. Among Democrats and independents who say it’s ideal for young children to have one parent at home at least part time, far more say it doesn’t matter which parent works part time or stays at home (56% of Democrats and 66% of independents) than say the mother (39% and 30%, respectively) or the father (4% of each) should be the one. Republicans offer more mixed views: 49% say the mother should stay home or work part time and 45% say it doesn’t matter which parent does this.

Educational attainment is also related to views of which parent should work part time or stay home with their young children. Among college graduates who say the ideal situation for children with a mother and a father is for one parent to work full time and one parent to either work part time or not work outside the home, about two-thirds (65%) say it doesn’t matter which parent doesn’t work full time; 30% say the mother should be the one who works part time or is not employed; and 5% say it should be the father. A narrow majority (55%) of those with some college education but without a bachelor’s degree say it doesn’t matter which parent stays home or works part time; 40% say it should be the mother; and 5% say it should be the father. By comparison, among those with a high school education or less, about as many say it doesn’t matter (49%) as say the mother should be the one who does not work full time (45%).