Veterans who served on active duty during the post-9/11 era consider themselves more patriotic than other Americans, and most see the military as an efficient and meritocratic institution. They have a more positive view than the general public about the overall worth of the Afghanistan and Iraq wars and the tactics the military has used to wage them. Even so, only one-third (34%) of these veterans say that both wars have been worth fighting.

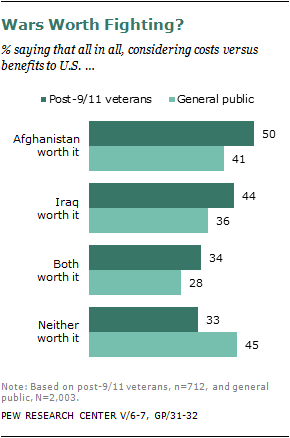

Looking at the conflicts individually, 50% of post-9/11 veterans say the decade-old war in Afghanistan has been worth fighting and 44% view the 8½-year-old conflict in Iraq the same way—approval levels that are nine and eight percentage points higher, respectively, than among the general public. Post-9/11 veterans also assess these wars somewhat more favorably than do veterans who served prior to the terrorist attacks a decade ago.

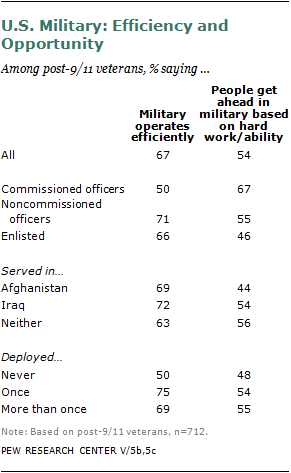

Post-9/11 veterans are more apt than the general public to say the military operates efficiently—67% vs. 58%. A majority (54%) of post-9/11 veterans think people generally get ahead in the military based on their hard work and ability, though veterans who served before 9/11 are more likely to say this (63%). By comparison, Americans overall are split 48%-48% on whether people generally get ahead in their job or career on the basis of hard work and ability.

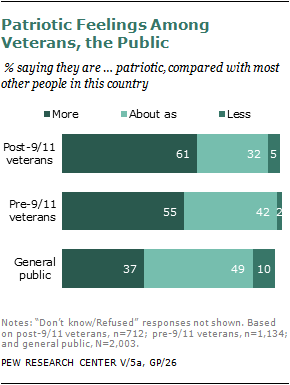

Patriotic sentiment runs far stronger among post-9/11 veterans, 61% of whom say they are more patriotic than most other people in the country, than it does among the general public (37%). Among pre-9/11 veterans, 55% say they are more patriotic than most other Americans.

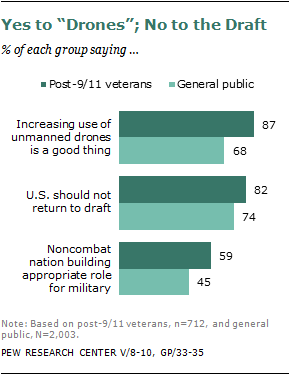

Those who have served since 9/11—for whom a part of their mission has been to try to rebuild social, political and economic institutions in Afghanistan and Iraq—are much more likely than the general public (by 59% to 45%) and veterans who served in earlier eras (also 45%) to view such noncombat “nation building” as an appropriate role for U.S. armed forces.

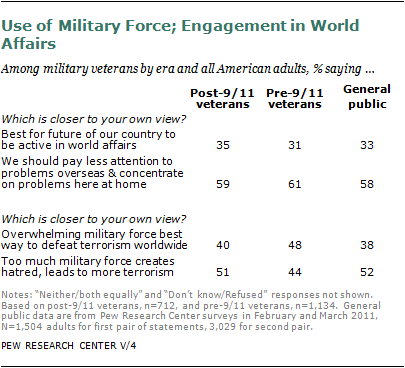

At the same time, however, many post-9/11 veterans have isolationist inclinations, with about six-in-ten saying the United States should pay less attention to problems overseas and concentrate on problems here at home. In a Pew survey conducted earlier this year, a similar share of the general public (58%) agreed.

Moreover, half (51%) of post-9/11 veterans say that overreliance on military force creates hatred that breeds more terrorism, while just four-in-ten say overwhelming military force is the best way to defeat terrorism. In the early 2011 Pew Research survey, the public divides in a nearly identical way on this question (52% vs. 38%).

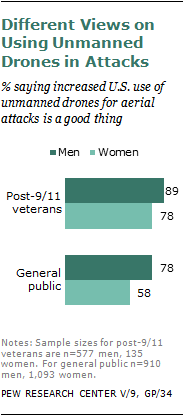

On a related matter, 87% of post-9/11 veterans say the U.S. military’s increasing use of unmanned “drone” aircraft for aerial attacks on individual enemy targets is a good thing. A smaller share of the general public (68%) agrees.

Asked their views on a long-abandoned method of staffing the military, 82% of post-9/11 veterans oppose reinstatement of the draft, which was abolished in 1973—though the new Pew survey of all adults hints at slightly softening opposition to the draft among all adults, at 74%, down 11 points from its high in an identical Gallup poll question in 2004.

Veterans are more likely than the general public to describe themselves as Republican (31% of all veterans, including 36% of those who served after 9/11, compared with 23% of all adults). And veterans overall are more apt to consider themselves conservative (48%) than are Americans overall (37%), although veterans who served after 9/11 do not differ significantly from the public in this regard (40% say they are conservative). In line with these partisan differences, fewer post-9/11 veterans (44%) than Americans overall (53% in the new Pew survey) approve of the way Obama is handling his duties as commander in chief.

The remainder of this chapter examines in greater detail how veterans and the general public judge the U.S. military and the wars it has been fighting in the post-9/11 era.

Approval of Afghanistan and Iraq Wars

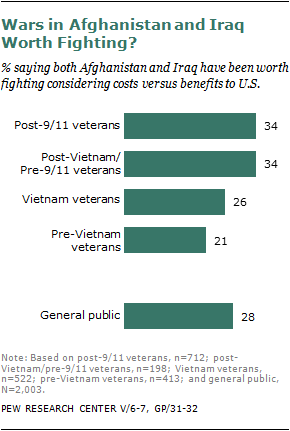

Veterans who have served since Vietnam, including post-9/11 veterans, are more likely than the general public and older veterans to approve of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. But skepticism remains substantial across the board.

Among all adults in the new Pew survey, 41% say that, considering the costs versus the benefits to the United States, the war in Afghanistan has been worth fighting, while 52% say it has not. Of the war in Iraq, 36% of Americans say it has been worth it and 57% say it has not. Fewer than three-in-ten Americans, 28%, say both wars have been worth fighting; 45% say neither has been worth it.

As noted, half of post-9/11 veterans (50%) say the war in Afghanistan has been worth fighting; 42% say it has not. And 50% of that group says Iraq has not been worth it, compared with 44% who view it positively. About as many post-9/11 veterans say neither war has been worth fighting (33%) as view both as being worthwhile (34%).

Veterans who served after Vietnam but before 9/11 hold similar views to the post-9/11 veterans, except somewhat fewer of the older veterans express no opinion one way or the other: 50% say Afghanistan has been worth it, 47% disagree and 3% don’t know; 45% say Iraq has been worth fighting, 53% say it has not and 2% don’t know. That leaves 34% of the post-Vietnam and pre-9/11 veterans saying both wars have been worth fighting and 37% saying neither war has been worthwhile.

Older veterans voice less approval of the effort in Afghanistan; just 33% who served before Vietnam say that war has been worth fighting, as do 39% of Vietnam veterans. By contrast, half of those who served subsequently say the Afghanistan War has been worth it. Nearly six-in-ten who served before and during Vietnam say Afghanistan has not been worth fighting (59% and 58%, respectively).

The Iraq War also gets less approval from older veterans; 35% who served before Vietnam and 36% who served during it say Iraq has been worth fighting, compared with 44% of all who have served in the military since Vietnam.

Among pre-Vietnam veterans, just one-in-five (21%) say both the Afghanistan and Iraq wars have been worth fighting, while more than twice as many, 47%, say neither has been worth it; the comparable figures for Vietnam-era veterans are 26% and 49% (and again, for the general public, 28% and 45%).

Views of Wars by Rank, Service in Theater, Casualties

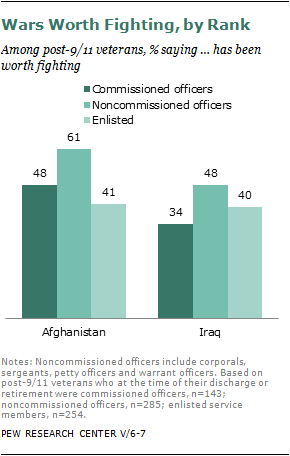

Among post-9/11 veterans, noncommissioned officers view the war in Afghanistan more approvingly (61% say it’s been worth fighting) than commissioned officers (48%) and enlisted service members (41%).7 Evaluations by rank regarding views of Iraq follow a similar pattern: 48% of noncommissioned officers say that war has been worth fighting, compared with 40% of enlisted service members and 34% of commissioned officers.

Veterans who served in or off the coast of Iraq or who flew missions over the country at any time since the war began in March 2003 are more likely—by 52% to 41%—to say that war has been worth fighting; 59% of post-9/11 veterans who did not deploy to the Iraqi theater say that war has not been worth fighting. Views of the Afghanistan War differed little between those who were and were not deployed in that theater (53% who had been deployed view that war approvingly, versus 50% who did not serve in Afghanistan). And the perceived worth of either war did not differ significantly between post-9/11 veterans who served with someone who was seriously wounded or killed in combat and those without exposure to such serious casualties.

How the U.S. Engages with the World

Back in the 1960s, President Lyndon Johnson emphasized the importance of winning “hearts and minds” of the people of Vietnam as a part of U.S. military objectives there. Today, “nation building” is a major component of the post-9/11 wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, as Americans not only wage battle but also try to rebuild the war-ravaged countries and their social, political and economic institutions. The new Pew survey finds that post-9/11 veterans are more likely than the general public and those who served during earlier wars—including in the Vietnam era—to consider it appropriate for the military to engage in such noncombat work.

Six-in-ten post-9/11 veterans (59%) say nation building is an appropriate role for the military, compared with just 45% of all those who served earlier and 45% of the general public. Approval for this noncombat role for the military varies slightly from about four-in-ten among World War II, Korean War and pre-Vietnam era veterans to 49% among Vietnam veterans. Among those who served after Vietnam but before 9/11, 44% say nation building is an appropriate role for the military.

Post-9/11 veterans see limits in how effective military force can be in combating global terrorism, as do most Americans. Asked which of two statements comes closer to their own views, 51% of post-9/11 veterans say that relying too much on military force to defeat terrorism creates hatred that leads to more terrorism, while 40% say that using overwhelming military force is the best way to defeat terrorism. Those figures are similar to the 52%-to-38% findings in a Pew Research survey of the general public earlier this year and are virtually unchanged from a December 2004 Pew Research survey.

Attitudes on this question are related to partisanship and ideology. Overwhelming force is preferred by 57% of post-9/11 veterans who consider themselves Republicans, 56% who call themselves conservative and 66% who say they’re both. By comparison, among post-9/11 veterans, 56% of Democrats say overreliance on force is counterproductive in fighting terrorism. (There were too few self-described liberals among this group of veterans to analyze with statistical reliability.)

A majority of post-9/11 veterans say the United States should be more inward-looking. Asked which of a pair of balanced alternatives comes closer to their own views, 59% said this country should pay less attention to problems overseas and concentrate on problems here at home, while 35% said it’s best for the future of the country to be active in world affairs.

Pre-9/11 veterans split similarly on this question, as did Americans overall in the Pew Research polling earlier this year (58% to 33%)—though that marked a shift among the general public from a December 2004 poll, conducted shortly after George W. Bush won a second term as president, when just 49% took the more isolationist position and 44% preferred a more active role for this country in world affairs.

Drones and the Draft

Almost all post-9/11 veterans approve of the use of unmanned aircraft known as “drones” for aerial attacks in Afghanistan, Iraq and elsewhere. Nearly nine-in-ten—87%—say the increased use of drones by the military is a good thing. The public agrees, but by a less lopsided margin—68% say it’s a good thing.

There’s a gap in opinion on this issue by gender: 89% of post-9/11 male veterans say the increased use of drones is a good thing, compared with 78% of female veterans. And among all adults, 78% of men but just 58% of women favor this tactic.

Veterans and the broader population both oppose bringing back the military draft. Among veterans, opposition to reinstating conscription is highest among those who served after 1973, when it was abolished—79% of all post-Vietnam veterans, including 82% who served since 9/11, say the United States should not return to the draft at this time. That compares with 61% of veterans who served while a draft was still in effect.

About three-quarters of U.S. adults (74%) oppose a return of the draft, while 20% favor it. The Gallup poll, using the same question wording, had found post-9/11 opposition to conscription increased from 69% in January 2003, shortly before the U.S. invasion of Iraq, to 85% in October 2004. Gallup last asked the question in August 2007, when opposition slipped slightly, to 80%.

Military Efficiency and Meritocracy

Although the wars it has waged in the past decade draw mixed reviews, the U.S. military gets high marks from its veterans for operating efficiently—67% of all veterans say that, with no difference overall by the era in which they served. A smaller share of the general public, 58%, shares that view.

Among post-9/11 veterans, 66% of veterans who were enlisted when they were discharged perceive the military as efficient, as do 71% of those who had been promoted to become noncommissioned officers. Just 50% of commissioned officers agree. Among pre-9/11 veterans, 60% of the enlisted personnel, 73% of noncommissioned officers and 64% of commissioned officers viewed the military as efficient.

There are wide differences among post-9/11 veterans on this measure depending on how many times they were deployed away from their permanent duty station. Some 50% of those who never deployed, 75% who were deployed once and 69% of those deployed multiple times view the military as efficient (the comparable shares of pre-9/11 veterans: 60%, 64% and 71%).

The military also gets largely positive grades for being a meritocracy, though less so from post-9/11 veterans. More than six-in-ten (63%) of pre-9/11 veterans say that generally speaking, people get ahead in the military based on their hard work and ability; 54% of post-9/11 veterans say that.

Among post-9/11 veterans who rose in rank to become noncommissioned or warrant officers, 55% view the military as a meritocracy. Some 46% of those who remained enlisted personnel agree with this assessment. Commissioned officers are more likely than either group to say the military is a meritocracy (67%).

In the survey of the general public, respondents were asked if they believed that throughout society as a whole, employees advanced on the basis of merit. They were less generous in their assessment. The public split evenly, 48%-48%, on whether people get ahead in their job or career based on hard work and ability.

Patriotism

Six-in-ten post-9/11 veterans (61%) consider themselves more patriotic than most other people in the country. Just 37% of Americans overall say that. A plurality of Americans (49%) say they are about as patriotic as most people in the country.

Among the most recent homecoming veterans, patriotism was felt especially strongly by those who served in Afghanistan (69%) or Iraq (68%), compared with 57% who served in neither.

Obama as Commander in Chief

Post-9/11 veterans give lower ratings than Americans overall to the way Obama is handling his duties as commander in chief—44% of those veterans approve and 47% disapprove, compared with a 53%-39% positive tilt among the general public. The views of pre-9/11 veterans are similar to those of post-9/11 veterans: 40% approve and 51% disapprove of the way the president is handling this aspect of his job.

Partisanship and ideology help explain these views; among post-9/11 veterans, 75% of Republicans and 65% of self-described conservatives disapprove, while 83% of Democrats approve of Obama’s handling of his commander in chief duties.

Post-9/11 veterans who disapprove of Obama as commander in chief also differ from those who approve in some views of how the country and military conduct their affairs in the world:

- 64% who disapprove, compared with 52% who approve, say this country should pay less attention to problems overseas and concentrate more on problems at home.

- Those who disapprove split fairly evenly on the use of force to defeat terrorism; 47% say using overwhelming military force is the best way to defeat terrorism and 46% say it can create hatred that breeds more terrorism. By contrast, post-9/11 veterans who approve of Obama as commander in chief are more inclined to say force can breed more terrorism; 60% feel this way.

- Those who disapprove (53%) are less likely than those who approve (63%) to view noncombat nation building as an appropriate role for the military.

- Post-9/11 veterans who view Obama negatively as commander in chief are more likely than their peers who rate him positively to say the war in Iraq has been worth fighting, by 51% to 37%. Regarding Afghanistan, however, there is no significant difference between these two groups: 53% of those who approve of Obama as commander in chief say that the war has been worth fighting, and 41% say it has not (6% don’t know); 51% of those who disapprove of Obama as commander in chief say Afghanistan has been worth fighting, and 46% say it has not (3% don’t know).