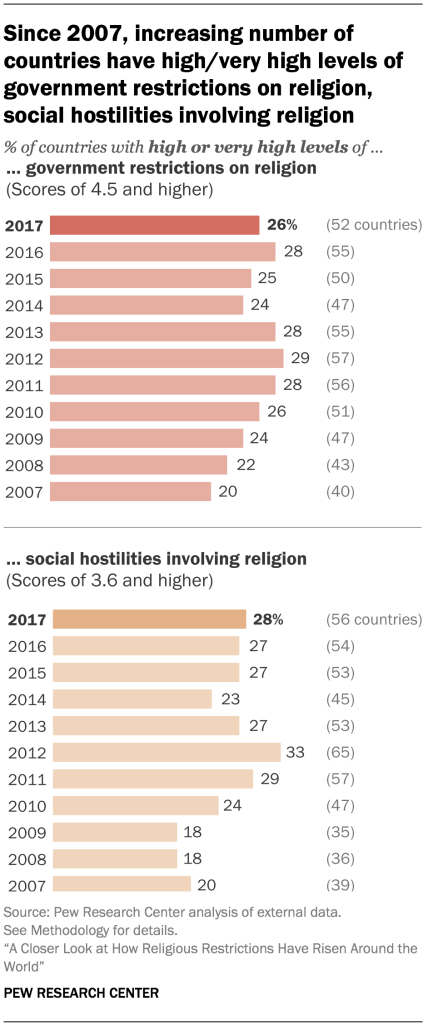

Over the decade from 2007 to 2017, government restrictions on religion – laws, policies and actions by state officials that restrict religious beliefs and practices – increased markedly around the world. And social hostilities involving religion – including violence and harassment by private individuals, organizations or groups – also have risen since 2007, the year Pew Research Center began tracking the issue. Indeed, the latest data shows that 52 governments – including some in very populous countries like China, Indonesia and Russia – impose either “high” or “very high” levels of restrictions on religion, up from 40 in 2007. And the number of countries where people are experiencing the highest levels of social hostilities involving religion has risen from 39 to 56 over the course of the study.

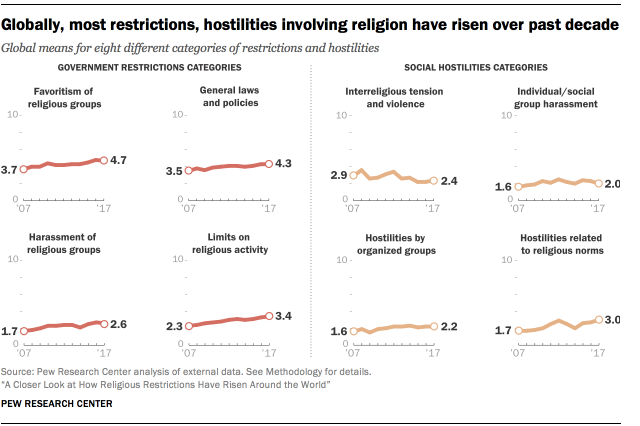

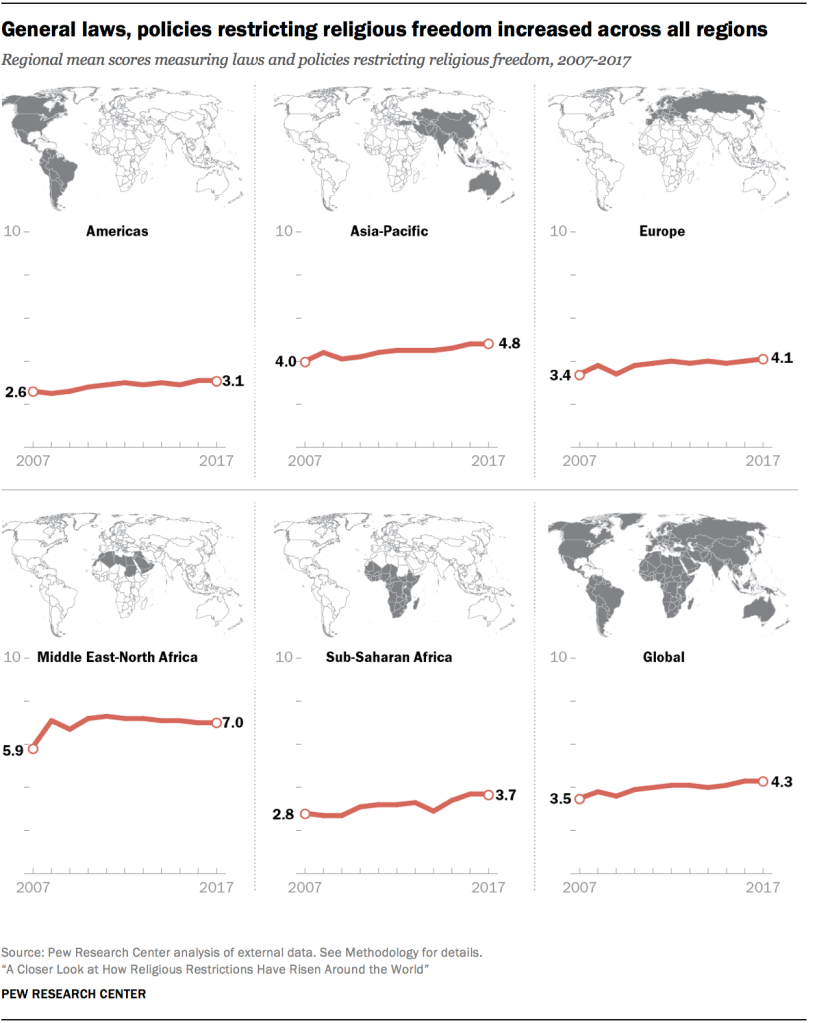

Government restrictions have risen in several different ways. Laws and policies restricting religious freedom (such as requiring that religious groups register in order to operate) and government favoritism of religious groups (through funding for religious education, property and clergy, for example) have consistently been the most prevalent types of restrictions globally and in each of the five regions tracked in the study: Americas, Asia-Pacific, Europe, Middle East-North Africa and sub-Saharan Africa. Both types of restrictions have been rising; the global average score in each of these categories increased more than 20% between 2007 and 2017.

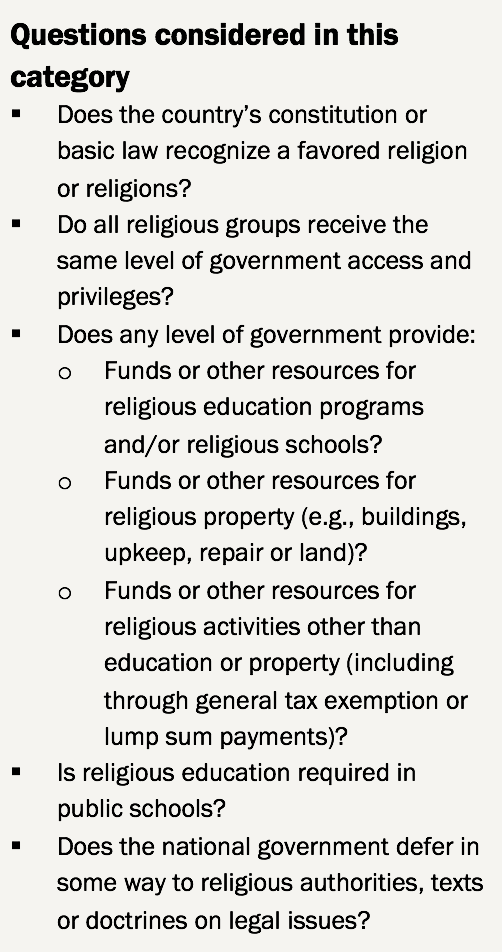

The Government Restrictions Index is made up of the following categories:

- Government favoritism of religious groups

- Laws and policies restricting religious freedom

- Government limits on religious activities

- Government harassment of religious groups

For more details on these categories, see here.

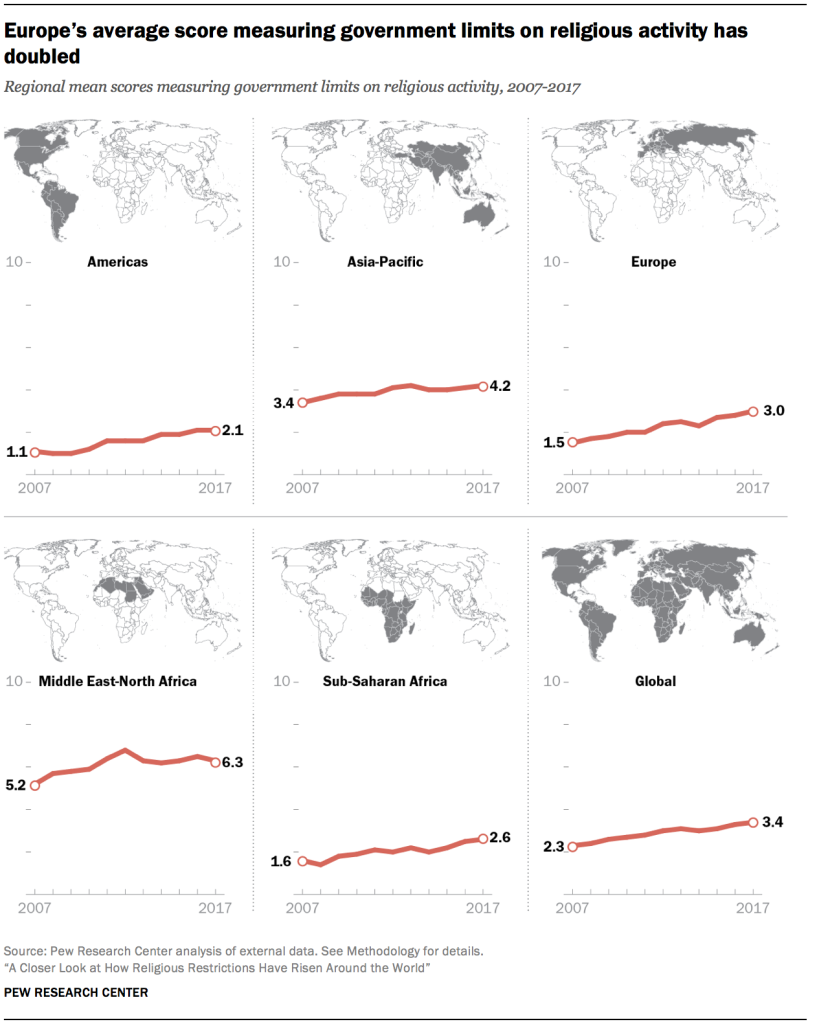

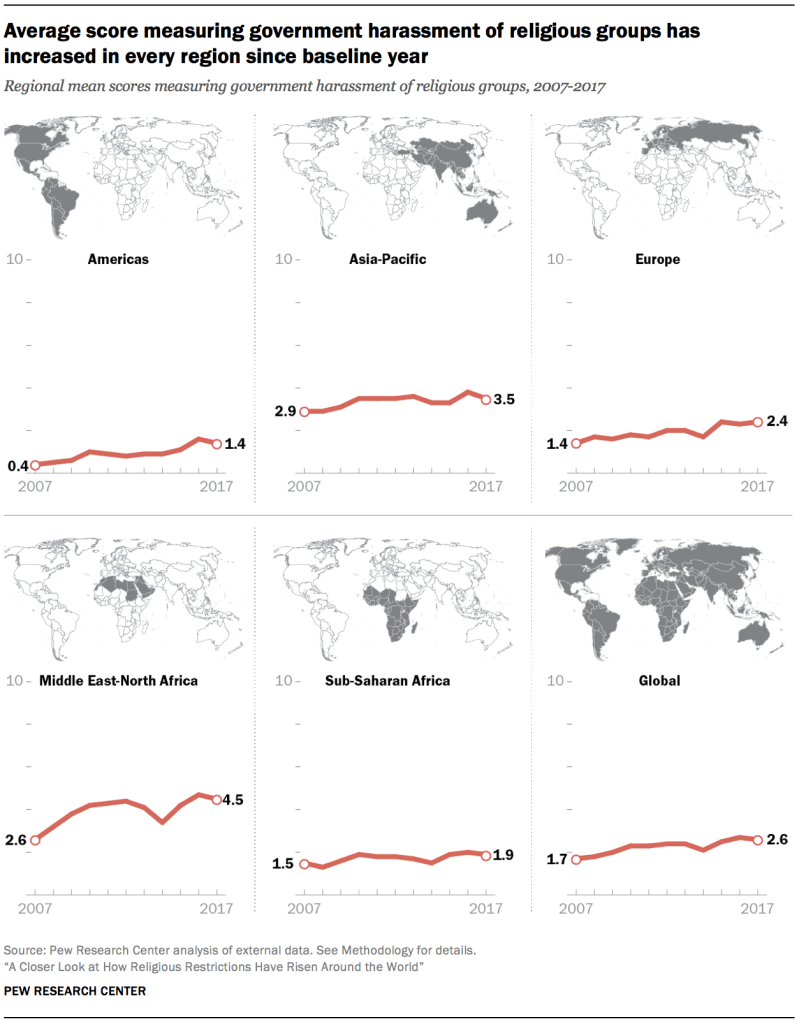

Levels of government limits on religious activities and government harassment of religious groups are somewhat lower. But they also have been rising over the past decade – and in some cases, even more steeply. For instance, the average score for government limits on religious activities in Europe (including efforts to restrict proselytizing and male circumcision) has doubled since 2007, and the average score for government harassment in the Middle East-North Africa region (such as criminal prosecutions of Ahmadis or other minority sects of Islam) has increased by 72%.1

The Social Hostilities Index is made up of the following categories:

- Hostilities related to religious norms

- Interreligious tension and violence

- Religious violence by organized groups

- Individual and social group harassment

For more details on these categories, see here.

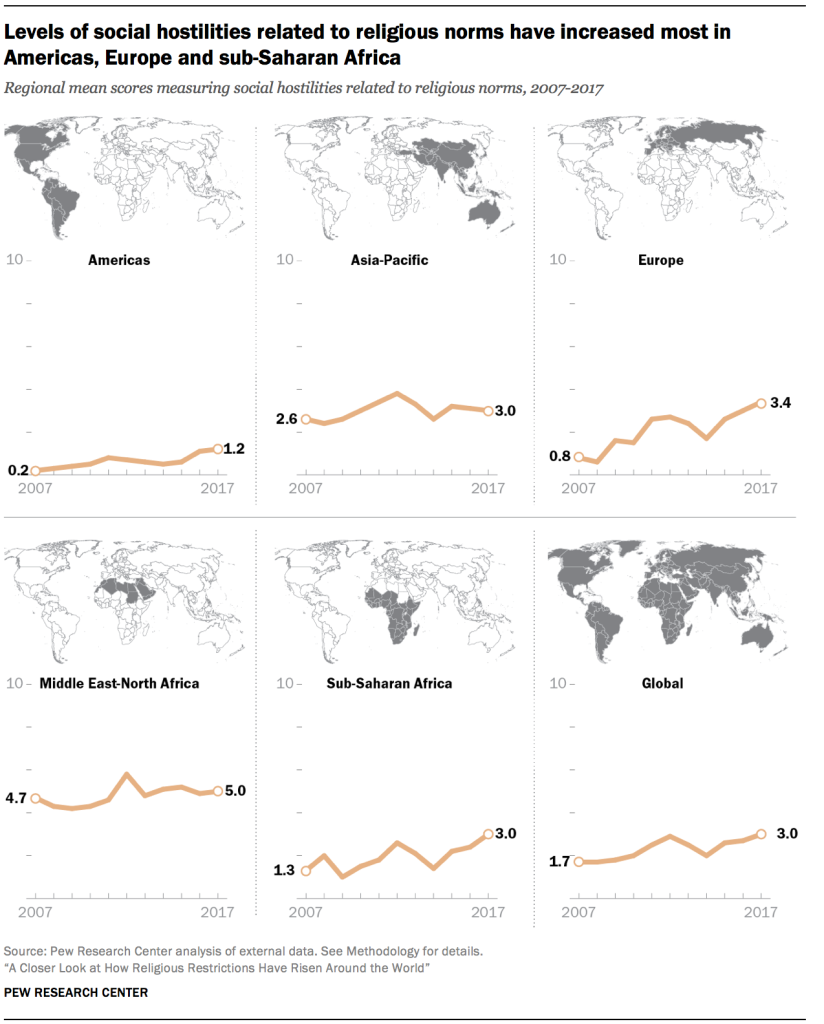

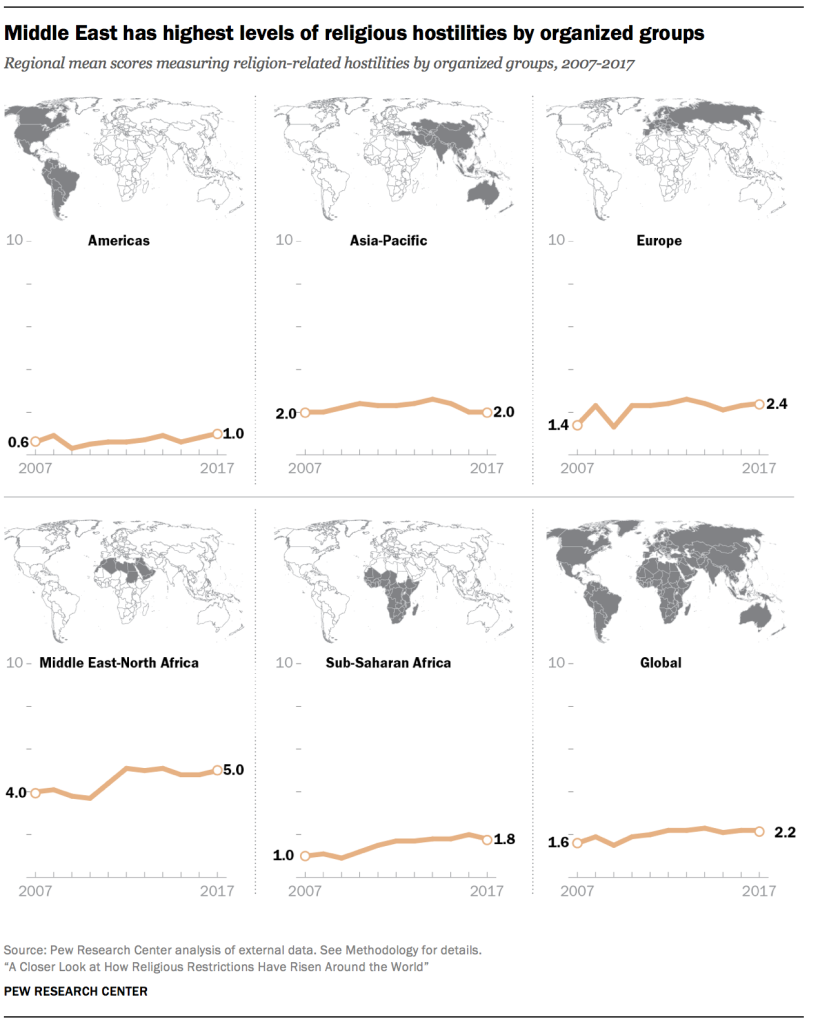

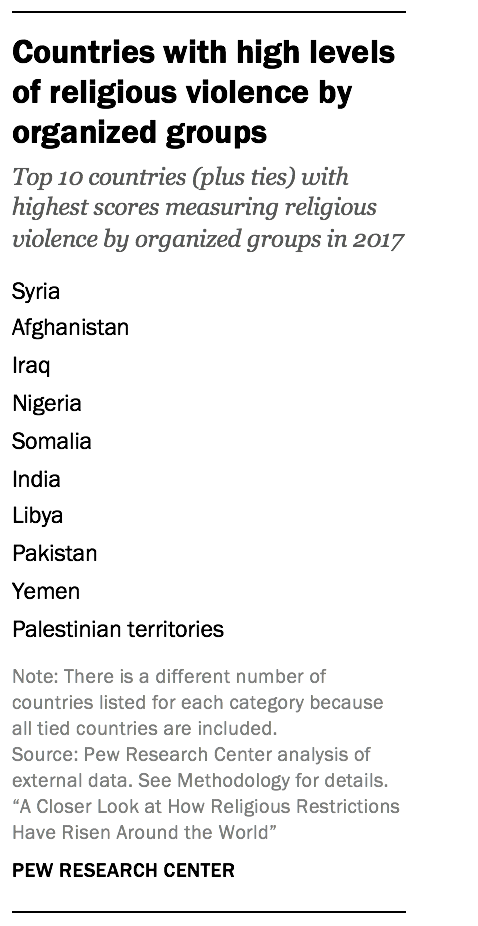

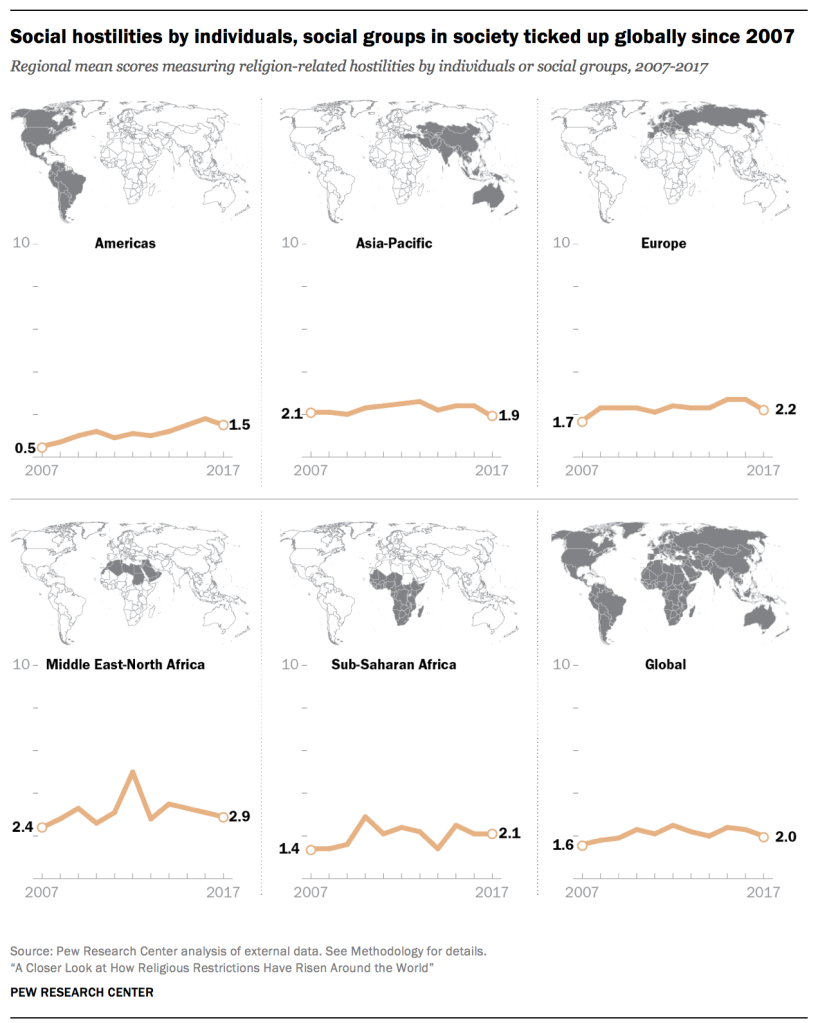

The global pattern has not been as consistent when it comes to social hostilities involving religion. One category of social hostilities has increased substantially – hostilities related to religious norms (for example, harassment of women for violating religious dress codes) – driving much of the overall rise in social hostilities involving religion. Two other types of social hostilities, harassment by individuals and social groups (ranging from small gangs to mob violence) and religious violence byorganized groups (including neo-Nazi groups such as the Nordic Resistance Movement and Islamist groups like Boko Haram), have risen more modestly.

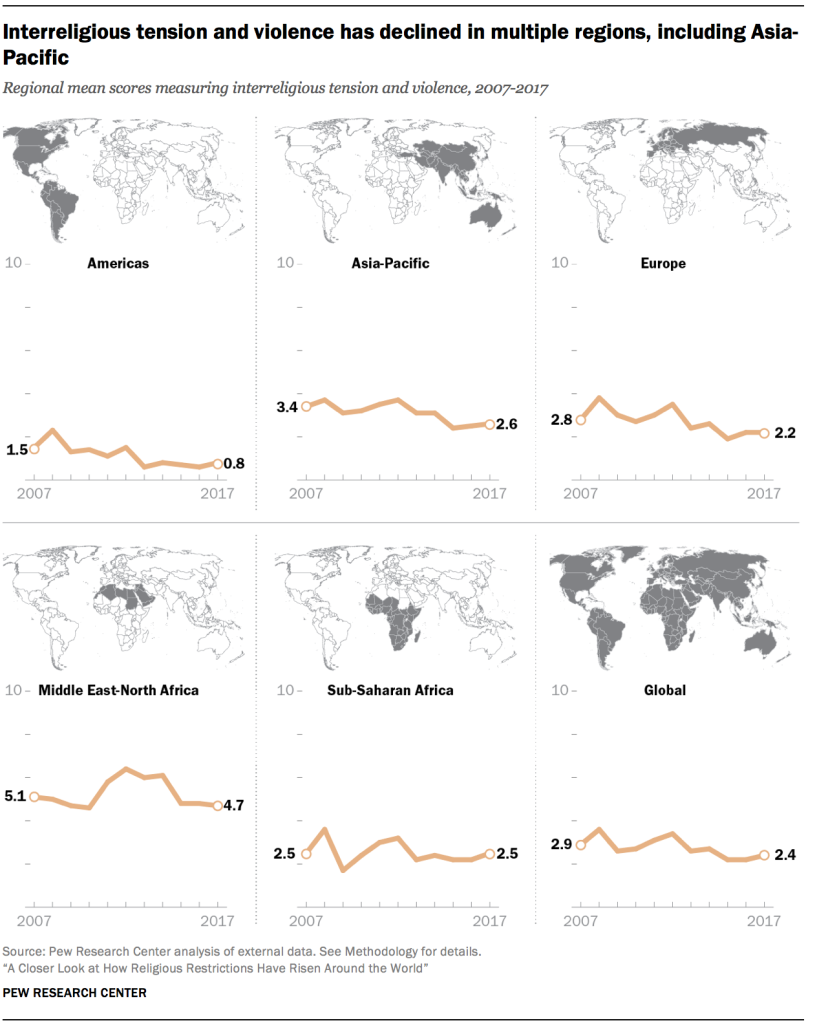

Meanwhile, a fourth category of social hostilities – interreligious tension and violence (for instance, sectarian or communal clashes between Hindus and Muslims in India) – has declined markedly since the baseline year (17%). By one specific measure, in 2007, 91 countries experienced some level of violence due to tensions between religious groups, but by 2017 that number dropped to 57 countries.2

These trends suggest that, in general, religious restrictions have been rising around the world for the past decade, but they have not been doing so evenly across all geographic regions or all kinds of restrictions. The level of restrictions started high in the Middle East-North Africa region, and is now highest there in all eight categories measured by the study. But some of the biggest increases over the last decade have been in other regions, including Europe – where growing numbers of governments have been placing limits on Muslim women’s dress – and sub-Saharan Africa, where some groups have tried to impose their religious norms on others through kidnappings and forced conversions.

This big-picture view of restrictions on religion comes from a decadelong series of studies by Pew Research Center analyzing the extent to which governments and societies around the world impinge on religious beliefs and practices. Researchers annually comb through more than a dozen publicly available, widely cited sources of information, including annual reports on international religious freedom by the U.S. State Department and the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom, as well as publications by a variety of European and UN bodies and several independent, nongovernmental organizations. (See Methodology for more details on sources used in the study.) Due to the availability of the source material and the time it takes to code, each annual Pew Research Center report looks at events that took place about 18 months to two years before its publication. For example, this report covers events that occurred in 2017.

The studies are part of the Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures project, which analyzes religious change and its impact on societies around the world. The project is jointly funded by The Pew Charitable Trusts and the John Templeton Foundation.

The previous reports have focused largely on year-over-year change, but this 10th report provides an opportunity for a broader look back at how the situation has changed around the world – and, more specifically, in particular regions and in 198 countries – over the length of the study. Also for the first time this year, researchers have broken down the two main, 10-point indexes used in the study – the Government Restrictions Index (GRI) and the Social Hostilities Index (SHI) – into four categories each.3

The categories can help give readers a sense of what goes into the broader GRI and SHI scores, and they also are useful when comparing countries that have similar overall scores but very different situations within their borders.

For instance, France and Qatar have similar overall GRI scores (both are in the “high” category”), but that does not mean that the lived experience of someone in those two countries is similar with respect to government restrictions on religion. France scores low in the category of government favoritism, while Qatar scores much higher (Islam is the official state religion, according to the constitution). And while Qatar scores lower on government harassment of religious groups, France has higher scores in this category, which includes enforcing restrictions on religious dress. France continues to enforce a national ban on full-face coverings in public, and local authorities also impose various restrictions that mostly affect Muslim women. In 2017, for example, the city of Lorette banned headscarves in a public pool.4 Laws regarding women’s religious dress also have boosted France’s score in the category of limits on religious activities, but Qatar scores even higher in this category, in part due to laws that target non-Islamic faiths by restricting public worship, the display of religious symbols and proselytization.5

For a full list of how all 198 countries and territories included in the study score in each category, see Appendix C. The remainder of this overview looks in more detail at the eight categories of restrictions on religion – four involving government restrictions and four involving social hostilities by private groups or individuals.

Categories of government restrictions on religion

The Government Restrictions Index measures government laws, policies and actions that restrict religious beliefs and practices. The GRI comprises 20 measures of restrictions, now grouped into the following categories:6

Government favoritism of religious groups

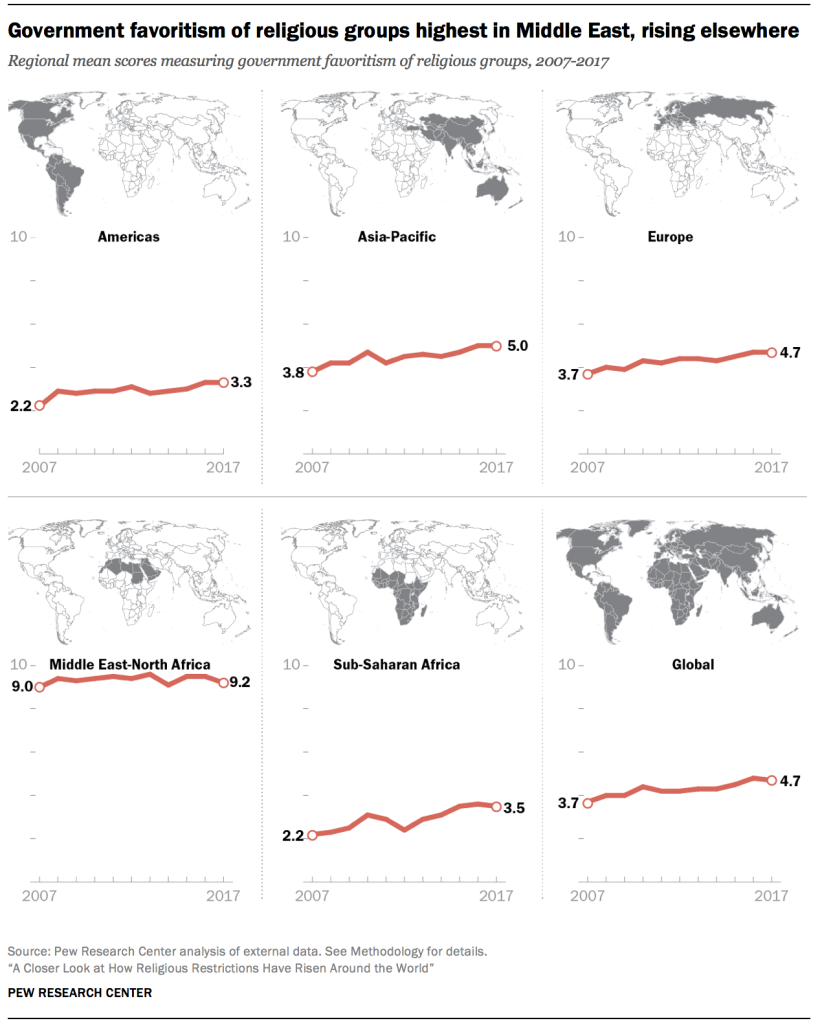

One of the consistent takeaways from a decade of tracking is the relatively high level of government restrictions on religion in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), which has ranked above all other regions each year from 2007 to 2017. The new study shows that the Middle East has high levels of restrictions across all four categories in 2017, but the gap in government favoritism is particularly large: The average country in the MENA region scores nearly twice as high on measures of government favoritism as the average country in any other region.

Indeed, 19 of the 20 countries in the Middle East (all except Lebanon) favor a religion — 17 have an official state religion, and two have a preferred or favored religion.7 In all of these countries except Israel, the favored religion is Islam. Additionally, all countries in the region defer in some way to religious authorities or doctrines on legal issues. For example, in family law cases in Egypt, when spouses have the same religion, courts apply that religious group’s canonical (i.e., traditional religious) laws. However, when one spouse is Muslim and the other has a different religion (such as Coptic Christianity), or if spouses are members of different Christian denominations, courts defer to Islamic family law.8

However, government favoritism has barely increased in the Middle East over the course of the study, partly because it started at such a high level that there was not much room for growth on the scale. In the other four major geographic regions, meanwhile, there have been notable increases in the levels of government favoritism of religious groups.

Some of the largest increases occurred in sub-Saharan Africa. For example, in 2009, Comoros passed a constitutional referendum that declared Islam the state religion.9 And, in 2014, a concordat between the island nation of Cabo Verde and the Vatican granted privileges to the Catholic Church that were not available to other groups. The agreement allowed for “Catholic educational institutions, charitable activities, and pastoral work in military, hospitals, and penal institutions, as well as Catholic teaching in public schools.” It also provided tax exemptions for Catholic properties and places of worship.10

In the Asia-Pacific region, government favoritism of particular religious groups also has increased since 2007. In Thailand, a new constitution came into force in 2017 with a provision that elevates the status of Theravada Buddhism by mandating “special promotion” through “education, propagation of its principles, and the establishment of measures and mechanisms ‘to prevent the desecration of Buddhism in any form.’”11 There also has been an increase in Asian governments deferring to religious authorities, texts and doctrines since 2007. For instance, in Turkey, the government passed a law in 2017 giving Muslim religious authorities at the province and district level the authority to register marriages and officiate at weddings on behalf of the state.12 The government contended that this would make the registration process more efficient, while critics argued that it violated principles of secularism in the country’s constitution and did not meet the needs of other (non-Muslim) religious groups.13

Most countries with the highest scores in government favoritism as of 2017 (including Afghanistan, Bahrain and Bangladesh) have Islam as their official state religion.14 This dovetails with an earlier finding that, as of 2015, Islam is the most common state religion around the world; in 27 of the 43 countries that enshrine an official religion (63%), that religion is Islam.

But not all the countries on this list favor Islam. In Greece, Iceland and the United Kingdom, different Christian denominations are the official state religions. The Greek government recognizes the Orthodox Church as the “prevailing religion” and funds the training of clergy, priests’ salaries and religious instruction in schools.15Iceland’s government provides the official state Evangelical Lutheran Church with financial support and benefits not available to other religious groups.16And in the UK, the monarch is the supreme governor of the Church of England, and must be a member of that church.17

At the country level, one of the largest increases since 2007 in the favoritism category occurred in the Pacific island nation of Samoa. In 2011, the Samoan government began to enforce a 2009 education policy that makes Christian instruction mandatory in public primary schools.18 And, in 2017, Samoa’s parliament amended the constitution to define the country as a Christian nation.19

For a full list of countries’ scores in this and other categories, see Appendix E.

Government laws and policies restricting religious freedom

Questions considered in this category

- Does the constitution, or law that functions in the place of a constitution (basic law), specifically provide for “freedom of religion” or include language used in Article 18 of the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights?

- Does the constitution or basic law include stipulations that appear to qualify or substantially contradict the concept of “religious freedom”?

- Taken together, how do the constitution/basic law and other national laws and policies affect religious freedom?

- Does the national government have an established organization to regulate or manage religious affairs?

- Does any level of government ask religious groups to register for any reason, including to be eligible for benefits such as tax exemption?

Along with favoritism, the broad category of “government laws and policies restricting religious freedom” includes some of the most common types of restrictions identified by the study. These restrictions can range from a constitution’s stated commitment to religious freedom (or lack thereof) to the regulation or registration of religious groups.

Again, the Middle East-North Africa region has higher levels of these restrictions than other regions, although after an initial rise from 2007 to 2008, the overall level of government laws and policies restricting religious freedom has been relatively stable in the MENA region as a whole. Other regions have seen recent increases in restrictions in this category – particularly sub-Saharan Africa, which experienced a sharp rise in government laws and policies restricting religious freedom between 2014 and 2017.

Rules on government registration of religious groups contributed heavily to the high scores in this category across all regions. Many countries require some form of registration for religious groups to operate, and at least four-in-ten countries in the Americas and more than half the countries in sub-Saharan Africa, the Asia-Pacific region and Europe had a registration process in 2017 that, at a minimum, adversely affected the ability of some groups to carry out their religious activities. In the Middle East and North Africa, this was the case in more than eight-in-ten countries.

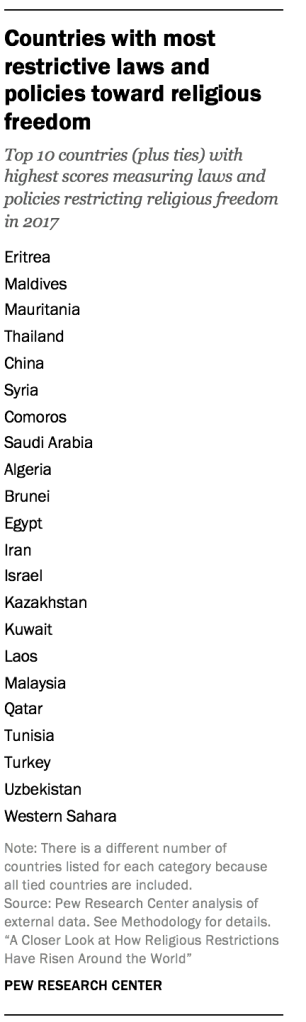

In some cases, governments recognize only a specific set of religious groups and deny registration (and, hence, official recognition) to all others. Elsewhere, bureaucratic hurdles create cumbersome registration processes that disadvantage particular groups. For example, in Eritrea, the government recognizes and registers only four religious groups — the Eritrean Orthodox Church, Sunni Islam, the Roman Catholic Church and the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Eritrea — and since 2002 no other groups have been registered or allowed to perform religious activities and services.20 And in Belarus, where there are extensive bureaucratic and legal requirements to be recognized, minority religious groups, such as Jehovah’s Witnesses and some Baptist groups, remain unregistered and face difficulties in carrying out religious activities.21

The countries with the highest scores in the category of laws and policies restricting religious freedom are spread across Asia, the Middle East and sub-Saharan Africa. In China, for example, only certain religious groups are allowed to register with the government and hold worship services. In order to do this, they must belong to one of five state-sponsored “patriotic religious associations” (Buddhist, Taoist, Muslim, Catholic and Protestant). However, there were reports that the Chinese government arrested, tortured and physically abused members of both registered and unregistered religious groups.22

In Saudi Arabia, meanwhile, a new counterterrorism law published in November 2017 criminalizes “anyone who challenges, either directly or indirectly, the religion or justice of the King or Crown Prince,” and prohibits “the promotion of atheistic ideologies in any form,” “any attempt to cast doubt on the fundamentals of Islam” and publications that “contradict the provisions of Islamic law.” Indeed, public practice of all non-Muslim religions is illegal in the country, including public worship, proselytization and display of religious symbols. It is also illegal for Muslims to convert to another religion.23

Since 2007, Hungary has experienced a large increase in its score in this category. A new law in 2012 changed the registration process for religious groups and effectively deregistered more than 350 groups, adversely affecting their finances and ability to offer charitable social services.24

Government limits on activities of religious groups and individuals

Questions considered in this category

- Does any level of government interfere with worship or other religious practices?

- Is public preaching by religious groups limited by any level of government?

- Is proselytizing limited by any level of government?

- Is converting from one religion to another limited by any level of government?

- Is religious literature or broadcasting limited by any level of government?

- Are foreign missionaries allowed to operate?

- Is the wearing of religious symbols, such as scarves or coverings for women and facial hair for men, regulated by law or by any level of government?

There has been a bigger increase in government limits on religious activities – such as restrictions on religious dress, public or private worship or religious literature – in Europe than in any other region during the course of the study.25

A growing number of European countries have placed restrictions on religious dress, with regulations that can range from prohibitions on wearing religious symbols or clothing in photographs for official documents or in public service jobs to national bans on religious dress in public places. In 2007, five countries were reported to have such restrictions in Europe, but by 2017, that number had increased to 20 countries. In Bosnia-Herzegovina, for example, employees of judicial institutions are prohibited from wearing “religious insignia” at work, including headscarves.26 And in France, a ban on full-face coverings was implemented in 2011; the ban prohibits Muslim women from wearing the burqa or niqab in public.27

The number of European governments that interfered in worship or other religious practices also has been on the rise since 2007. In Moldova, for example, several local councils in 2012 banned Muslim worship in public.28 And that same year in the United Kingdom, the high court found that a Scientologist’s allegation of discrimination was not valid after the Church of Scientology was barred from holding legal marriage ceremonies because it was not “a place of meeting for religious worship.”29 Meanwhile, in Germany and Slovenia, Muslim and Jewish groups protested government interference in circumcision of boys. In Germany, a district court ruling in Cologne in 2012 criminalized male circumcision for nonmedical reasons, classifying it as assault. Following complaints, the federal government introduced a new law later in the year to address the concerns of both Muslims and Jews by allowing the practice for religious reasons.30 And in Slovenia, Muslim and Jewish groups accused the Slovenian ombudswoman for human rights – a government figure – of religious discrimination after she called child circumcision a criminal offense.31

Government limits on religious activities also have increased markedly in the Americas, where the number of countries where governments interfered with worship rose from 16 in 2007 to 28 in 2017. In Canada, for example, the Supreme Court denied constitutional protection to a territory of spiritual significance to the indigenous Ktunaxa Nation in 2017. The Ktunaxa Nation had in 2012 sought a judicial review of a decision to approve the construction of a ski resort on land that was central to their faith, claiming it would impinge on their religious practices and violate their religious freedom.32

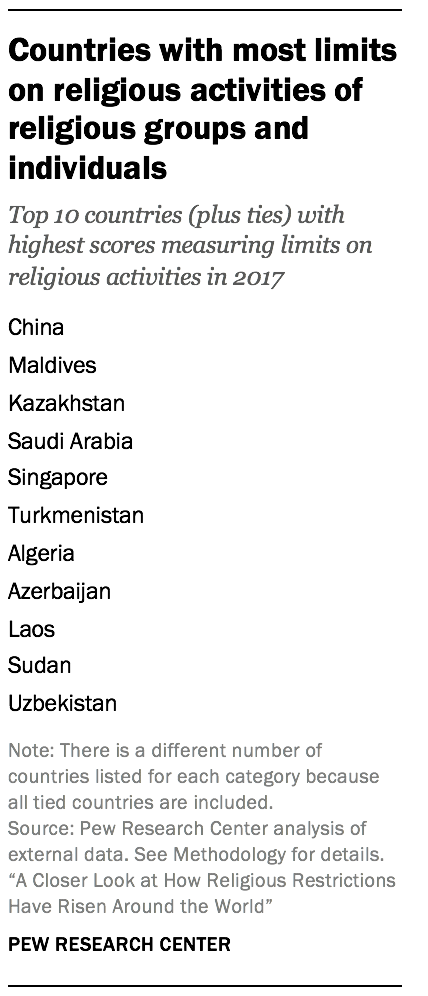

In other regions, too, government limits on religious activities have risen over the course of the study. This includes the Middle East-North Africa region. For instance, limits on public preaching have increased notably since 2007, when 13 countries were reported to have such restrictions. In 2017, 18 out of 20 countries in the region reportedly limited public preaching. These types of restrictions are not limited to minority faiths. In Jordan, for example, the government monitored sermons at mosques and required preachers to abstain from talking about politics to avoid social and political unrest and to counter extremist views. The Jordanian government began distributing themes and recommended texts for sermons to imams at mosques in 2017, and those who did not follow the recommendations were subject to fines and preaching bans.33

Additionally, in sub-Saharan Africa, the government has increasingly regulated the wearing of religious clothing. In 2015, four countries — Cameroon, Chad, the Republic of Congo and Niger — banned Islamic veils for women in response to terror attacks within their borders.34

Among the countries with the highest levels of limits on religion, myriad policies restricting religious activities are enforced. In the Maldives, for example, it is a criminal offense to promote a religion other than Islam, punishable by up to five years in jail.35 And in Laos, religious groups must get permission from the government in order to gather, hold religious services, build houses of worship and establish new congregations.36

Restrictions in this category also are common across Central Asia. As of 2017, the government in Turkmenistan continued to deny visas to foreigners if they were suspected of intending to do missionary work; the government also prevented the importation of religious literature.37 Similarly, in Uzbekistan, a government agency continued to block the importation of both Christian and Islamic literature.38 And a Kazakh law states that production, publication and dissemination of religious literature is allowed only after approval from the government.39

Spain has experienced some of the largest increases in its score for government limits on religious activities since 2007. In 2010, several cities in Catalonia introduced bans on the burqa and niqab (full-body and head coverings) as well as face-covering veils in public buildings. Additionally, the country’s largest opposition party also proposed a ban on the niqab in all public places, though it was ultimately rejected.40 And, in more recent years, religious groups such as Latter-day Saints (sometimes called Mormons) and Jehovah’s Witnesses have faced restrictions on public preaching and proselytizing from local governments in Spain.41

Government harassment of religious groups

Questions considered in this category

- Was there harassment or intimidation of religious groups by any level of government?

- Did the national government display hostility involving physical violence toward minority or non-approved religious groups?

- Were there instances when the national government did not intervene in cases of [social] discrimination or abuses against religious groups?

- Did the national government denounce one or more religious groups by characterizing them as dangerous “cults” or “sects”?

- Does any level of government formally ban any religious group?

- Were there instances when the national government attempted to eliminate an entire religious group’s presence in the country?

- Did any level of government use force toward religious groups that resulted in individuals being killed, physically abused, imprisoned, detained or displaced from their homes, or having their personal or religious properties damaged or destroyed?

Not only are there higher levels of government harassment of religious groups in the Middle East-North Africa region compared with other regions, but MENA also has experienced the biggest increase in this category since the baseline year. This category measures types of harassment ranging from violence and intimidation to verbal denunciations of religious groups and formal bans on certain groups.

An increasing number of governments in MENA have reportedly used force against religious groups (including detention and forced displacement) since 2007. In Algeria, for example, more than 280 Ahmadis were prosecuted due to their religious beliefs in 2017.42 And in the same year in Saudi Arabia, authorities began to demolish a 400-year-old Shiite majority neighborhood and displaced thousands of people in what the government described as counterterrorism efforts.43

The Asia-Pacific region also stands out as relatively high in this category. For example, in 2017 alone, harassment or intimidation of religious groups by governments was reported in 86% of countries in the region.44 This measure includes long-term, ongoing harassment of religious minorities in some countries, which continued in 2017. For example, in China, hundreds of thousands of Uighur Muslims reportedly were sent to “reeducation camps.”45 Religion-related harassment in Burma (Myanmar) also has received global attention in recent years. In 2017, there were numerous reports of large-scale abuses against the Rohingya, a Muslim ethnic minority in the country. The military reportedly carried out extrajudicial killings, rapes, torture, beatings, arbitrary arrests and detentions, and restrictions on religious practice, which contributed to large-scale displacement. There also were reports that Rohingya were denied citizenship.46

Harassment also increased in Europe and Americas since the baseline year of the study, particularly between 2014 and 2016. For example, in 2015, religious groups in 38 out of 45 countries (84%) in Europe experienced at least limited levels of harassment, compared with 32 countries (71%) the previous year. Some incidents of government harassment — which can include derogatory statements and intimidation by public officials — were in response to record numbers of migrants entering Europe in 2015. For example, in the Netherlands, opposition parliamentarian Geert Wilders campaigned against the “Islamization of the West,” and in September 2015 led a protest against a “tsunami of refugees from Islamic countries who threaten our women and our civilization.”47

In the Americas, the sharpest increase in the government harassment category occurred between 2015 and 2016. That year, there was at least limited harassment in 32 countries, compared with 28 countries in 2015. In Cuba, for instance, members of religious groups advocating for greater religious and political freedom reportedly were threatened by the government.48

Harassment of religious groups is particularly high in Iran, where authorities have labeled Baha’is as “heretical” and “filthy,” and Russia, where police have raided religious minorities’ homes and places of worship.49 In Indonesia, local governments continued efforts to force conversions of Ahmadi Muslims by requiring them to sign forms renouncing their beliefs before they could register marriages or participate in the hajj pilgrimage.50

When it comes to increases since 2007 in this category, Bahrain stands out. Anti-government protests that began in 2011 took on a sectarian dimension, with the Sunni government targeting mostly Shiite opposition protesters and religious leaders. In 2016, the government carried out a security operation in a predominantly Shiite village where protesters were demonstrating in support of the country’s most senior Shiite cleric, whose citizenship had been revoked. Authorities cut off access to the village, used live ammunition to clear the area and killed five civilians, injured many others, and arrested nearly 300 people.51

Categories of social hostilities involving religion

The Social Hostilities Index measures acts of religious hostility by private individuals, organizations or groups in society. The SHI includes 13 measures of social hostilities, grouped into the following categories:

Hostilities related to religious norms

Questions considered in this category

- Did individuals or groups use violence or the threat of violence, including so-called honor killings, to try to enforce religious norms?

- Were individuals assaulted or displaced from their homes in retaliation for religious activities, including preaching and other forms of religious expression, considered offensive or threatening to the majority faith?

- Were women harassed for violating religious dress codes?

- Were there incidents of hostility over proselytizing?

- Were there incidents of hostility over conversions from one religion to another?

Social hostilities involving religion have been consistently high in the Middle East-North Africa region compared with other regions throughout the length of the study. This is true across all four subcategories of social hostilities.

But social hostilities in MENA have been relatively stable between 2007 and 2017. Meanwhile, the largest increasein the category of social hostilities related to religious norms – and, in fact, in any category – occurred in Europe.

In 2007, just four European countries were reported to have individuals or groups who used violence, or threat of violence, to try to force others to accept their own religious practices and beliefs; by 2017, it had risen to 15 countries. For example, in the United Kingdom in 2016, a Sunni Muslim man killed an Ahmadi Muslim shopkeeper because he had “disrespected the Prophet Muhammad.”52 And in Ukraine in 2015, separatists held four Jehovah’s Witnesses at gunpoint, subjected them to beatings and mock executions and forced them to confess Orthodox Christianity as the only true religion.53

There also was an increase in assaults on individuals for religious expression considered offensive or threatening to the majority faith. In 2007, six European countries were reported to have such hostilities; by 2017, that number had climbed to 25 (out of a total of 45 countries in Europe). In Belgium, a rabbi reported in 2016 that stones were thrown at him and a friend because he was “visibly Jewish.”54 The previous year, a young Jewish man wearing a yarmulke was assaulted by two men. And in a separate incident, a Muslim woman was attacked by two women who took off her veil and verbally abused her for being Muslim.55

In sub-Saharan Africa, hostilities related to religious norms also have risen since the baseline year of the study. In 2007, incidents of violence used to enforce religious norms were reported in eight countries, while in 2017, 31 out of 48 countries in the region experienced this type of hostility. In Burkina Faso, for example, armed men entered classrooms in multiple schools and threatened to kill teachers if they did not teach the Quran to their students.56 Killings of people accused of witchcraft also occurred throughout the region. In 2017, there were reports of attacks on people accused of practicing witchcraft in five countries — Angola, Central African Republic, Lesotho, Liberia and South Africa.

Since 2007, there also has been an increase in hostilities over conversions in the region. In 2007, five countries in sub-Saharan Africa experienced such hostilities; by 2017, that number doubled, to 10 countries. In Djibouti, for instance, Christian groups reported that Christian converts faced discrimination in employment and education.57 And in Nigeria, girls abducted by the terrorist group Boko Haram were subjected to forced religious conversion and other abuses.58

There has been a substantial increase in the Americas’ score in this category over the course of this study, but the score started from a very low base in 2007 and remains substantially lower than all other regions’ scores.

Several Western European countries rank among those with the highest scores in the category of social hostilities related to religious norms. In Germany, for instance, one sociologist estimated that there were thousands of conversions to Christianity – more than during all of the previous 50 years – linked to the rising number of refugees. Religious groups reportedly “used refugees’ fear of deportation to promote conversions and incentivized them by offering accelerated baptism, free lunch and transportation costs,” according to a radio program cited by the U.S. State Department’s annual report on religious freedom.59 In France, Jehovah’s Witnesses faced violence when proselytizing door to door or engaging in other missionary activity.60 And in Russia, following a Supreme Court ban on Jehovah’s Witnesses in 2017, several threats and attacks on the group were reported. The Russian Orthodox Church supported the ban, saying it would combat the “spread of cultist ideas, which have nothing in common with Christian religion.”61

Elsewhere, the Taliban in Afghanistan killed or threatened Sunni clerics for preaching messages the Taliban considered un-Islamic, and in 2015, some Algerians promised “retribution” against women who went out uncovered, threatening to publish pictures of unveiled women on the internet or to attack them by pouring acid on their faces.62 In Israel, drivers who operated cars near ultra-Orthodox Jewish neighborhoods on the Sabbath reported incidents of harassment, including name-calling and spitting, by ultra-Orthodox residents.63

Germany and Uganda had some of the largest increases in social hostilities related to religious norms. In Uganda, for example, Christians were beaten and three were killed for religious reasons in Muslim-majority areas in 2015. The same year, three children were kidnapped because of their father’s conversion from Islam to Christianity.64 And in 2016, several incidents of violence against converts were reported, including a woman whose husband strangled her to death for leaving Islam.65

Interreligious tension and violence

Questions considered in this category

- Were there acts of sectarian or communal violence between religious groups?

- Did violence result from tensions between religious groups?

- Did religious groups attempt to prevent other religious groups from being able to operate?

Interreligious tension and violence involves acts of sectarian or communal violence betweenreligious groups. Such tensions can carry over from year to year, and are not necessarily reciprocal.66

Interreligious tension and violence was the most common type of social hostility in the early years of the study. But unlike all other categories of both government restrictions and social hostilities involving religion, interreligious tension and violence has declined since 2007 globally and in most regions (except sub-Saharan Africa), and by 2017, the average country’s score was higher in the religious norms category than in this one.

In the Asia-Pacific, Europe and Middle East-North Africa regions, the specific measure of tensions that involved numerous cases of physical violence between religious groups dropped in recent years in at least some countries. In Armenia, for instance, no violent attacks against Jehovah’s Witnesses were reported in 2017, unlike in 2012, when Jehovah’s Witnesses faced an attack from supporters of the Armenian Apostolic Church.67 And in Tunisia, there were no reported attacks in 2017 by Salafists – who follow fundamentalist interpretations of Sunni Islam – on Sufi and Shiite Muslims, as had been reported in previous years. (This may be in part due to Salafists being closely monitored and restricted by the government after the deadly Bardo Museum attacks in 2015.68)

Still, in 2017, more than half of countries in sub-Saharan Africa and the Asia-Pacific region, and more than eight-in-ten countries in the Middle East-North Africa region, experienced some kind of communal tension between religious groups.

Communal violence has long been common in India, which continued to score high in this category in 2017. According to media reports, a dispute between two Hindu and Muslim high school students in Gujarat escalated into a mob attack on the village’s Muslim residents; homes and vehicles were set on fire and about 50 homes were ransacked by the mob.69

There also were tensions between Christians and Muslims in Nigeria – the most populous country in Africa, and one that is almost evenly divided between the two religious groups. For example, Muslim herders carried out retaliatory attacks against Christian farmers after herders said they did not receive justice when the farmers killed members of the herding community and stole their cattle.70

In Iraq, there was Sunni-Shiite fighting following the liberation of certain areas from ISIS rule. There were reports that after the city of Tal Afar was freed from ISIS in 2017, Shiite militias arrested, kidnapped and killed Sunnis.71

Despite a modest decline in overall interreligious tensions since 2007, there were still some notable increases in this category, particularly in Syria and Ukraine. Syria has been experiencing a civil war since 2011 that has had a large sectarian component, with violence between religious groups reported throughout the conflict.72 And in Ukraine, tensions between the Ukrainian Orthodox Church-Moscow Patriarchate (UOC-MP) and the Ukrainian Orthodox Church-Kyiv Patriarchate (UOC-KP) along with the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church (UGCC) have persisted. In 2017, UGCC followers and a priest took control of a UOC-MP church, assaulted members and called UOC-MP parishioners “Moscow’s pigs.” UOC-MP leaders also claimed that the UOC-KP continued to seize churches belonging to the UOC-MP.73

Religious violence by organized groups

Religious violence by organized groups includes the actions of religion-related terrorist groups, religion-related conflict, and the use of force by organized groups to dominate public life with their perspective on religion. Since 2007, the largest increases in this category of social hostilities have occurred in Europe and the Middle East-North Africa region.

As in all other categories of government restrictions and social hostilities involving religion, the Middle East and North Africa has seen the highest levels of religious violence by organized groups. Over the years, the actions of religion-related terrorist groups have increased especially sharply in this region. In 2007, four countries in this study were recorded as having more than 50 injuries or deaths from religion-related terrorism incidents. By 2017, that figure climbed to 11 of the 20 countries in the region. These include deadly attacks in Egypt in 2017, when armed gunmen carrying the ISIS flag attacked a Sufi mosque in northern Sinai, leaving 311 dead. And on Palm Sunday, suicide bombings at two Coptic churches in the country – which ISIS claimed responsibility for – left 45 people dead.74

In Europe, meanwhile, organized groups have increasingly used force or coercion in an attempt to dominate public life with their perspective on religion. In the baseline year of the study, this type of hostility was reported at the local, regional or national level in a total of 21 European countries. By 2017, that figure had risen to 33 countries.For example, in Finland, the Nordic Resistance Movement, a neo-Nazi group, published anti-Semitic and anti-Muslim material and organized small-scale training camps and rallies. They published content on their website asserting that Jews had brought Muslims to Europe and that “Finns must become informed about racial violence against white persons and diseases spread by Muslim immigrants,” according to the U.S. State Department’s annual report on religious freedom.75 The group also organized multiple antireligious activities in Sweden in 2017. In September, roughly 500 supporters of the group marched through the city of Gothenburg on the Jewish holiday Yom Kippur, clashing with police and thousands of counterdemonstrators.76

Many of the countries with high levels of religious violence by organized groups have active Islamist militant groups within their borders. This includes ISIS and other groups in Syria, al-Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula in Yemen, al-Shabaab in Somalia, the Taliban in Afghanistan and Hamas in the Palestinian territories.

Nigeria is among the countries with the largest reported increases in religious violence by organized groups since 2007. The Islamist militant group Boko Haram became increasingly active in the country, “committing abuses such as mass killings, kidnappings, sexual assault, forced conversion and forced conscription,” according to the U.S. State Department’s annual report on religious freedom. In a particularly high-profile case in 2014, the group kidnapped more than 200 schoolgirls – who were mostly Christian – from a school in Chibok in Borno state.77

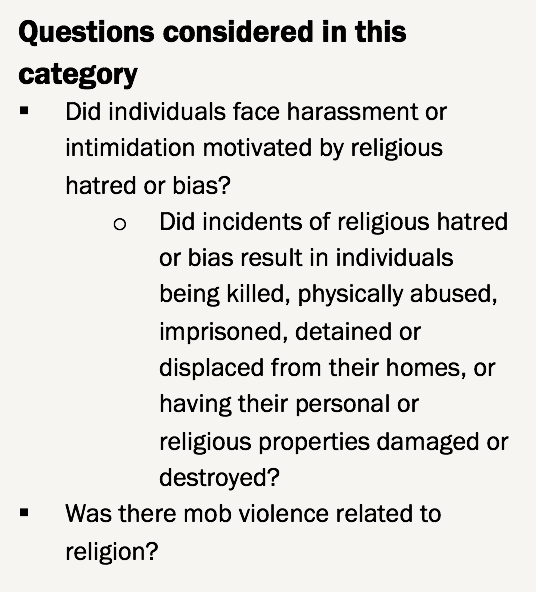

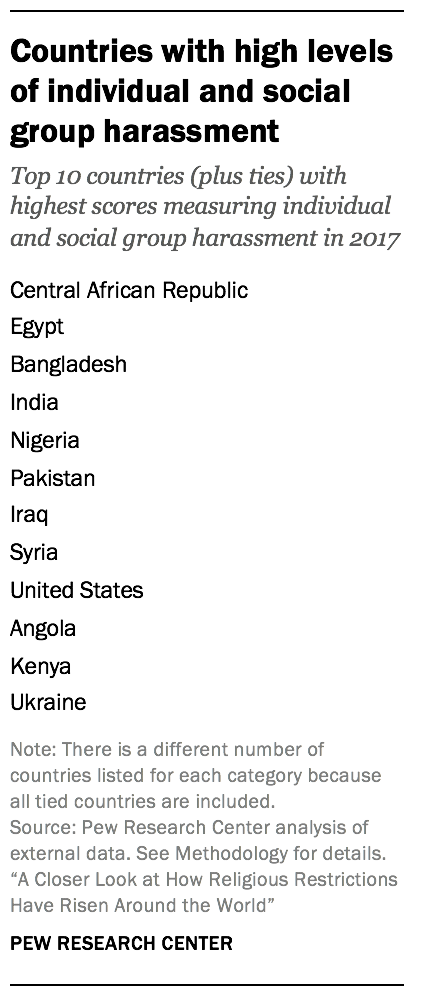

Individual and social group harassment

Social harassment of religious groups is a broad category that ranges from actions by individuals to mob violence.78 Harassment also can include discrimination or publishing of articles or cartoons that are derogatory toward a certain group. This category also includes property damage, detentions or abductions, displacement, physical assault and deaths of members of religious groups caused by private individuals or social groups.

The Middle East and North Africa again has almost always had the highest levels of hostilities in this category (sub-Saharan Africa had the highest level in 2010). The Americas, meanwhile, has the lowest levels of all the regions, but also has experienced the largest increasein this type of hostility since 2007. In Brazil, there were pockets of anti-Semitic and anti-Muslim sentiment in 2017 as well as incidents targeting Afro-Brazilian religions. In the state of Sao Paulo, arsonists burned down an Afro-Brazilian temple in September, one of eight attacks against Afro-Brazilian targets in the state in that month.79

There was a considerable uptick in this category in 2012 in the Middle East and North Africa in the aftermath of the Arab Spring uprisings in late 2010 and 2011. The increase was particularly pronounced in Syria, where there was a rise in people being targeted due to their faith, exacerbated by government efforts to quell what had started as anti-government protests. As the conflict worsened and the government increasingly targeted Sunni Muslims, revenge attacks by Sunnis against Alawites — who were seen as supporting the regime — also escalated.80

Some of the countries with the highest levels of individual and social group harassment in 2017 experienced incidents of mob violence, including Bangladesh – where in November 2017 a mob of approximately 20,000 in Rangpur set fire to and vandalized approximately 30 homes belonging to the local Hindu minority community after a Facebook post demeaned the Prophet Muhammad.81 In Pakistan, there were several incidents of mob attacks in response to accusations of blasphemy.82

The U.S. also ranked among the highest-scoring countries in this category in 2017, in part because of the “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, where white supremacists were protesting the removal of a Confederate statue from a park. Protesters expressed anti-Semitic and racist sentiments, displaying swastika flags and chanting “Jews will not replace us!”83

Central African Republic experienced a particularly large increase in its score in this category. In the midst of a violent conflict between Christian and Muslim militia forces, there have been widespread killings and displacement of people. Muslims have been disproportionately displaced – approximately 80 percent have been forced to flee the country.84

Overall restrictions in 2017

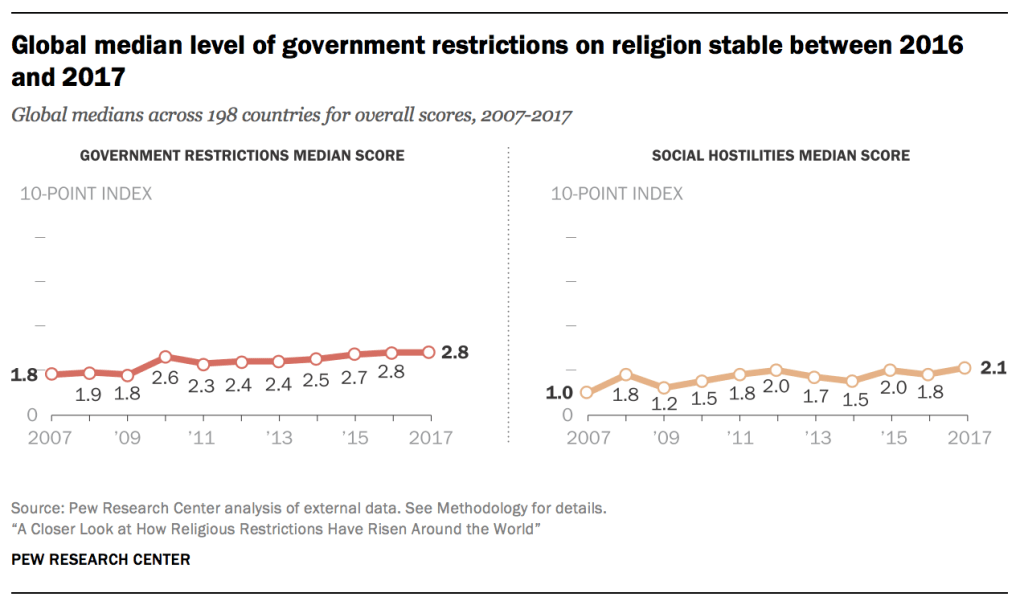

Overall, government restrictions on religion and social hostilities involving religion remained fairly stable in 2017, compared with the previous year. This marks the first time there was little change globally after two consecutive years of increases on overall restrictions carried out either by governments or by private groups and individuals.

In 2017, about a quarter of the 198 countries studied (26%) experienced “high” or “very high” levels of government restrictions — that is, laws, policies and actions by government officials that restrict religious beliefs and practices — falling from 28% in 2016. This decrease follows two years of increases in the percentage of countries with high levels of restrictions on religion by these measures (see here).

The share of countries with “high” or “very high” levels of social hostilities involving religion — that is, acts of religious hostility by private individuals, organizations or groups in society — ticked up from 27% in 2016 to 28% in 2017. This is the largest percentage of countries to have high or very high levels of social hostilities since 2013, but falls well below the 10-year peak of 33% in 2012.

In 2017, 83 countries (42%) experienced high or very high levels of overall restrictions on religion, from government actions or hostile acts by private individuals, organizations and social groups. This figure has remained at the same level since 2016 following two years of increases and is just below the 10-year peak of 43% in 2012. As in previous years, most countries continue to have low to moderate levels of overall religious restrictions in 2017.

Looking separately at global median scores can provide another understanding of how religious restrictions are changing. The global median score on the Government Restrictions Index remained the same at 2.8 from 2016 to 2017 after three years of increases. And the global median score on the Social Hostilities Index increased slightly from 1.8 to 2.1 in 2017.

The rest of this report looks more closely at the changes in 2017, the most recent year for which data is available.