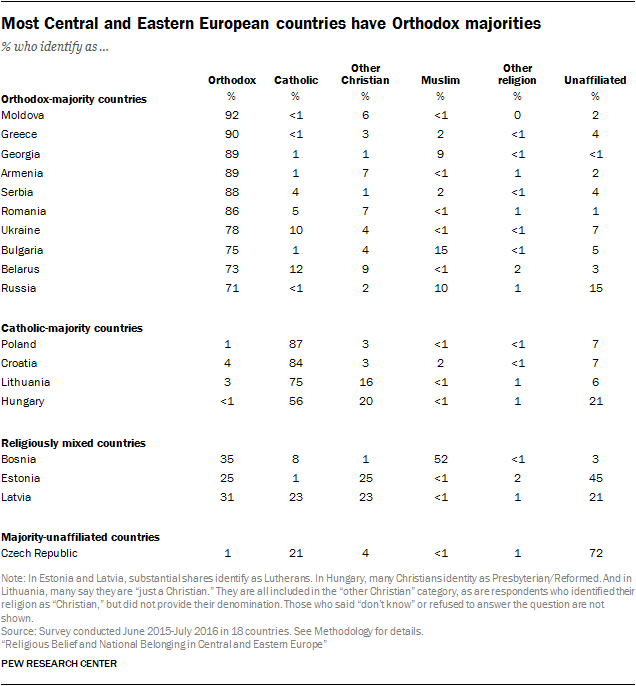

Orthodoxy is the dominant religion in Central and Eastern Europe, and the majority religion in 10 of the 18 countries surveyed. Overall, nearly six-in-ten people in the region (57%) identify with this Christian tradition. Moldova and Greece have the highest Orthodox proportions in their populations, while Russia and Ukraine – the two largest countries surveyed in terms of overall population – have the largest Orthodox populations in absolute numbers.

The region also has sizable populations of Catholics and Muslims and notable shares of Lutherans in some countries. The Czech Republic is the only country surveyed in which a majority of adults say they are religiously unaffiliated (i.e., they describe their religion as atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular”).

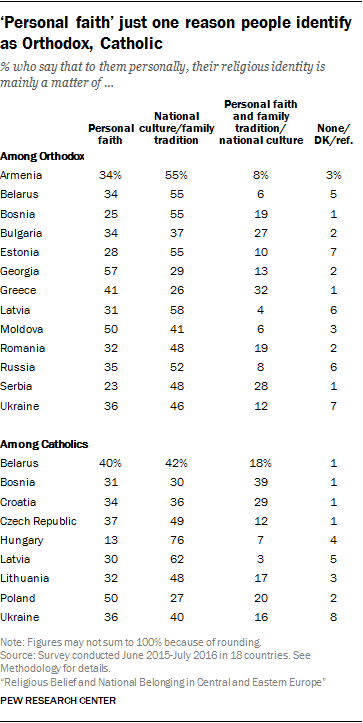

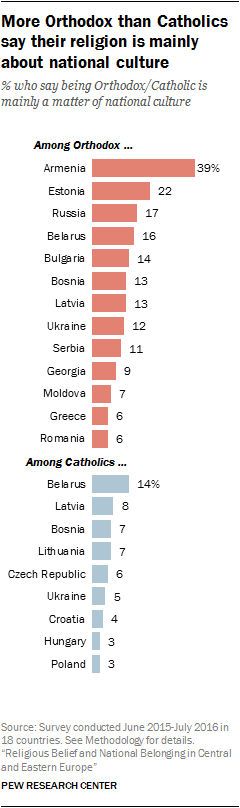

The survey asked Christian respondents whether they view their religious identity primarily as a matter of personal faith, a matter of family tradition or a matter of national culture. Responses vary across different countries, but generally, the shares emphasizing ancestral and cultural aspects of their religious identity are similar to or larger than the shares who stress the personal faith aspect. Overall, Orthodox Christians are more likely than Catholics to say their religious identity is primarily about national culture.

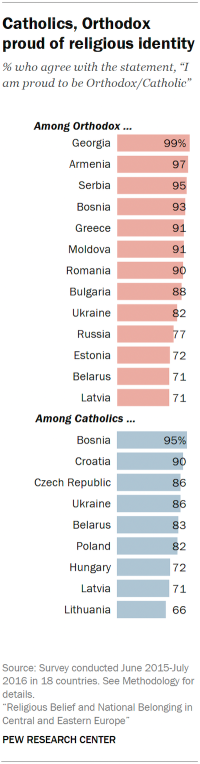

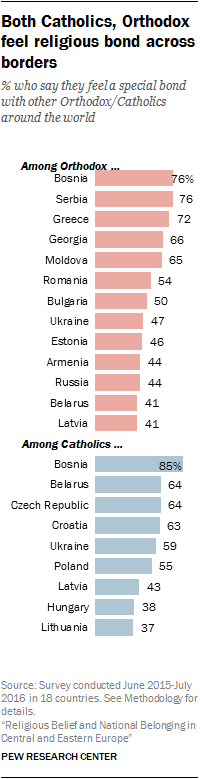

Large majorities of religiously affiliated adults in each country surveyed say they take pride in their religious identity. Fewer, though close to half in most countries, say they feel strong bonds with fellow members of their religious group around the world. Smaller percentages say religion is very important in their personal lives.

Respondents in former Soviet republics are more likely to say religion is important to them now than to say it mattered to their families when they were children; in other countries surveyed, on balance, more people say religion was important to them growing up than say it is important to them now. Similarly, when asked about religion on a national level, in most countries that were part of the officially atheist USSR, higher shares say their country is at least somewhat religious now than say it was as religious in the 1970s and 1980s.

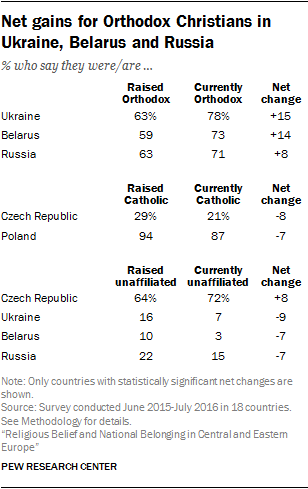

Most adults in the countries surveyed say they were raised in the religion with which they currently identify (or with no religion, if they are now unaffiliated). To the extent that people have changed religions, or have joined a religion after being raised without one, they have tended to become Orthodox. In Belarus, Russia and Ukraine, many adults now say they are Orthodox after having been raised with no religion – a change likely connected to the fall of the Soviet Union – while far fewer have become religious “nones” after being raised Orthodox.

On the other hand, in the Czech Republic, and to a lesser extent in Poland, there has been a shift away from Catholicism. Net losses for Catholics in the Czech Republic have meant net gains for the ranks of the religiously unaffiliated.

A highly varied religious landscape

Central and Eastern Europe is home to three-quarters of the world’s Orthodox population.18 Orthodox Christians make up 57% of the region’s population, and form religious majorities among adults in 10 of the countries included in this survey.19 Russia and Ukraine have the largest populations of Orthodox Christians in absolute terms – approximately 100 million and 35 million, respectively. Moldova (92%), Greece (90%), Georgia (89%), Armenia (89%) and Romania (86%) have the highest percentages of Orthodox Christians in their adult populations.

Still, the region’s religious landscape is diverse. Four of the 18 countries surveyed have Catholic majorities: Poland (87% Catholic), Croatia (84%), Lithuania (75%) and Hungary (56%). In these countries, relatively few adults identify as Orthodox.

In one country, the Czech Republic, a majority of the adult population (72%) claims no religious affiliation – the highest share, by far, of any country surveyed. Roughly one-in-five Czechs (21%) are Catholic. (For more details, see sidebar on religion in the Czech Republic in this report’s Overview.)

Three countries – Bosnia, Estonia and Latvia – are so religiously diverse that no single group forms a clear majority. All three have sizable Orthodox minorities (35% in Bosnia, 25% in Estonia and 31% in Latvia). Latvia and Estonia also have substantial populations of Lutherans and religiously unaffiliated people; in fact, a plurality of Estonians (45%) are religious “nones.” Nearly a quarter of Latvians (23%) are Catholic. And, in Bosnia, about half of adults (52%) are Muslim and 8% are Catholic.

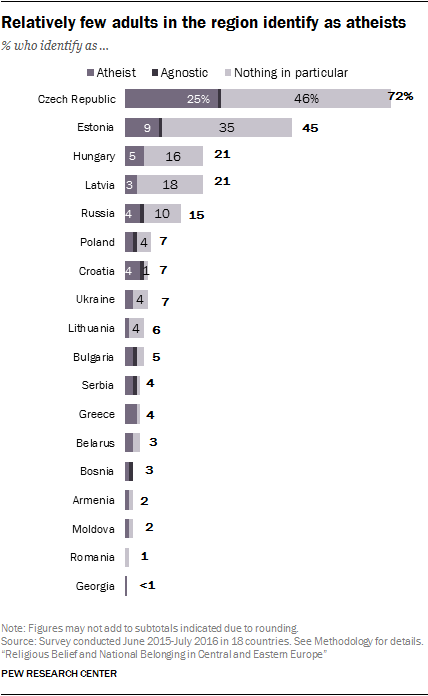

In most countries, small shares are religiously unaffiliated

By many standard measures, this region is less religious than others surveyed by Pew Research Center. (See Chapter 3 for a discussion of religious beliefs and comparisons with other regions.) Still, the wide reach of religion is evident in the relatively low share of respondents across the region who do not identify with a religion at all. In most countries surveyed, fewer than one-in-ten adults identify as religiously unaffiliated (that is, as atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular”).

The two major exceptions are the Czech Republic and Estonia, where religious “nones” make up 72% and 45% of surveyed adults, respectively. In the Czech Republic, 46% of adults say they have no particular religion, while a quarter (25%) identify as atheists. In Estonia, 35% say they have no particular religion and 9% say they are atheists. Fewer in either country describe themselves as agnostics.

Only in a handful of other countries surveyed does the share of religiously unaffiliated people reach double digits. In Russia, 15% say they are unaffiliated – a big decrease from the waning days of the Soviet Union a few decades ago, when a majority of Russians said this about themselves (see Overview).

Those who are unaffiliated seem content to stay that way. In countries with sufficient sample sizes, large majorities of religious “nones” say they are not looking for a religion.

The lasting effects of tension within the Estonian and Latvian Lutheran churches

Most Central and Eastern Europeans identify with either the Orthodox or Catholic churches. However, historically, sizable Lutheran populations have been present in Estonia and Latvia (including 79% and 55%, respectively, in 1939); today, roughly one-in-five adults in each country identify as Lutheran (20% and 19%, respectively).20

That said, the arrival of Lutheranism in the Baltic region was anything but smooth. By the mid-1500s, much of the local German nobility had converted the peasant class from Catholicism or Orthodoxy to Lutheranism. These nobles maintained influence in the area until the 20th century. While many Latvians and Estonians remained Lutheran during the interwar years of independence, some still associated Lutheranism with the German upper classes, and centuries of foreign influence encumbered the relationship between the Lutheran churches and most of the population.21

During the Soviet era, other factors contributed to the tension. First, in both countries the Lutheran churches typically capitulated to Soviet demands, which included banning religious instruction. Furthermore, ties between Estonian Lutheran leadership and the KGB (the former Russian secret police and intelligence agency) were later revealed.22 And as the push for independence grew in the late 1980s and early 1990s, church leaders were replaced due to internal opposition to the leaders’ Soviet ties.

Some of this history may be reflected in the new survey’s results. Centuries of foreign domination within the church may contribute to Latvia and Estonia having the lowest percentages of respondents saying that membership in the national church (in both cases, the Lutheran church) is very or somewhat important to being truly Latvian or Estonian (11% and 15%, respectively).

In addition, survey respondents in Estonia and Latvia are among the least likely of the 18 countries surveyed to say religion is very important in their lives (6% and 10%, respectively). These shares are substantially lower than the regional median of 26%.

Family tradition and national culture important aspects of religious identity for both Catholics and Orthodox

The survey asked Christian respondents to choose whether, for them personally, their religious identity (Orthodox, Catholic, Lutheran, etc.) is mainly a matter of personal faith, family tradition or national culture. (Respondents could volunteer more than one response.)

With few exceptions, Orthodox and Catholic respondents are about as likely or more likely to say their religious identity is primarily about national culture or family tradition as they are to say it is about personal faith. For example, in Belarus, more than half (55%) of Orthodox Christians say that being Orthodox, to them, personally, is mainly about family tradition (37%) or about national culture (16%), while about a third (34%) say it is mainly about personal faith. And Catholics in Belarus are about as likely to say being Catholic is mainly about personal faith (40%) as they are to say it is about family tradition or national culture (42%).

Generally, people who are more religious – that is, who pray daily or say religion is very important in their life – are more likely than others to say being Catholic or Orthodox is mainly a matter of personal faith.

Overall, the “national culture” option is chosen more frequently by Orthodox Christians than by Catholics. For example, 39% of Orthodox Christians in Armenia, 22% in Estonia, 17% in Russia and 16% in Belarus say that to them, being Orthodox is mainly a matter of national culture. By contrast, around one-in-ten or fewer Catholics across the region, including just 3% in Poland and Hungary, say being Catholic is mainly a matter of national culture.

Vast majority of both Orthodox and Catholics say they are proud of their religious identity

Religious identity is a source of pride for the vast majority of Orthodox Christians and Catholics surveyed in the region.

About nine-in-ten Orthodox Christians in Romania, Moldova, Greece, Bosnia and Serbia say they are proud to be Orthodox, and this sentiment is nearly universal in Georgia and Armenia. It is lower, though still widespread, in the countries with the two largest Orthodox populations: Russia (77%) and Ukraine (82%).

Catholic pride is expressed at similar levels, and by large majorities, in every country surveyed with a substantial Catholic population. Nine-in-ten or more Catholic adults in Bosnia and Croatia say they are proud to be Catholic, as do at least eight-in-ten in the Czech Republic, Ukraine, Belarus and Poland.

Overall, people who pray daily, attend church weekly or say religion is very important in their lives are more likely than others to say they take pride in their religious identity. And, on balance, women are more likely than men to express pride in their religion.

Many Catholics, Orthodox Christians feel connected to co-religionists around the world

The survey also asked people if they feel special bonds to other members of their religious tradition around the world. Overall, Catholics across the region are about as likely as Orthodox Christians to say they feel this type of special bond. But in countries with sizable shares of both Catholic and Orthodox populations, Catholics are generally more likely to say they feel a bond with other Catholics than Orthodox Christians are to say they feel a special bond with other members of their branch of Christianity. In Ukraine, for example, 59% of Catholics say they feel a special bond with Catholics around the world, while just 47% of Orthodox Christians in Ukraine report feeling such a bond with other Orthodox Christians.

Orthodox Christians in former Soviet republics surveyed are less likely than those elsewhere to express that they feel this kinship. For instance, only 44% of Orthodox Christians in Russia say they feel a special bond with other Orthodox Christians around the world, compared with about three-quarters in Bosnia and Serbia (both of which were outside the USSR’s borders).

Overall, Catholic adults ages 35 and older are more likely than younger adults to say they feel a bond with Catholics elsewhere. And among both Catholics and Orthodox Christians, people who are more religious are more likely to say they feel a bond with other members of their religious group around the world.

The survey also asked if Catholic and Orthodox adults have a special responsibility to support fellow followers of their traditions around the world. Overall, majorities or pluralities of Orthodox Christians in most countries agree they feel such a sense of responsibility. The pattern is more mixed among Catholic populations – in about half the countries where adequate sample sizes of Catholics are available for analysis, majorities or pluralities agree with this view, while in other countries, fewer Catholics take this position.

Once again, religious people – those who pray daily, attend church weekly or say religion is very important in their personal lives – are more likely than others to say they have an obligation to support co-religionists around the world.

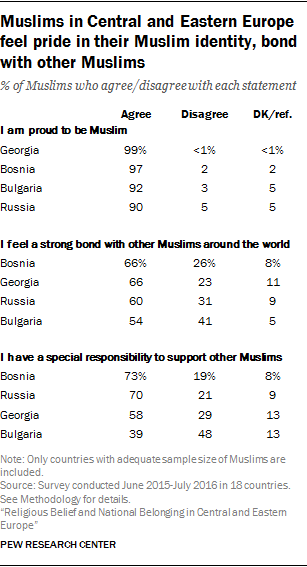

Muslims express pride, connectedness and responsibility

While Christianity is the region’s dominant religion, four of the 18 countries surveyed have enough Muslim respondents to allow for separate analysis.

In each of these countries, overwhelming majorities of Muslim adults say they are proud to be Muslim, ranging from 90% in Russia to 99% in Georgia. At least half say they feel strongly connected to other Muslims around the world. And majorities in Bosnia, Russia and Georgia say they feel a special responsibility to support other Muslims.

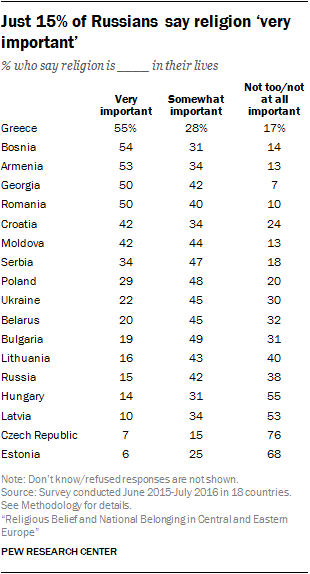

Fewer than half in most countries say religion ‘very important’

While many people across different religious groups in the region take pride in their religious identity and feel connected to others with their religious background, smaller shares say religion is “very important” to them, personally. In half the countries surveyed, fewer than a third of adults say religion is very important in their personal lives. Only in Greece, Bosnia, Armenia, Georgia and Romania do roughly half of respondents say religion is very important to them. People are least likely to say this in Estonia (6%) and the Czech Republic (7%).

(For survey results on attendance at religious services, daily prayer and various other religious practices, see Chapter 2.)

Overall, Catholics and Orthodox Christians in the region are about equally likely to rate religion as very important in their daily lives, although in most countries with substantial Catholic and Orthodox populations, it is Catholics who are more likely to say this. In Belarus, for example, 30% of Catholics say religion is very important to them, compared with 17% of Orthodox Christians.

Among the four countries surveyed with substantial Muslim populations, only in Bosnia (59%) do a majority of Muslims say religion is very important in their lives.

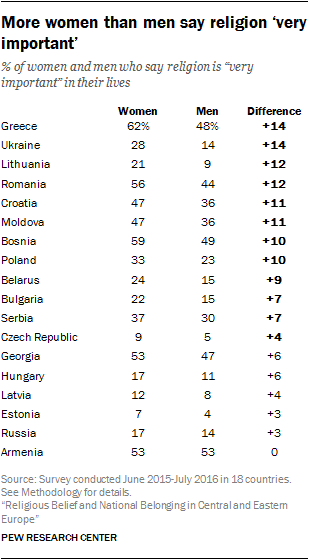

In most countries surveyed, women are more likely than men to say religion is very important to them. In Greece, for example, 62% of women say this, compared with 48% of men. A 14-point gap also exists in Ukraine, where 28% of women and 14% of men say religion is very important in their lives.

Respondents without college degrees also are more likely than those with more education to say religion is very important to them.

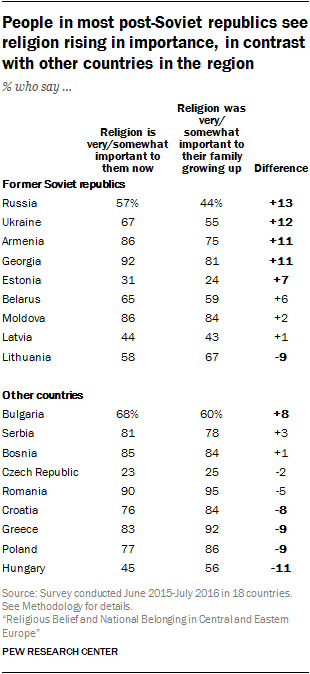

In former Soviet republics, people tend to say religion is more important to them now than it was growing up

In addition to asking respondents about how important religion is to them now, the survey also asked how important it was to their families when they were growing up.

On balance, in former Soviet republics, people are more likely to say religion is important in their lives now than to say it was important growing up. In Russia, for example, 57% say religion is either very important or somewhat important in their lives now, compared with 44% who say that was true during their childhoods.

These findings are in line with answers to a related set of questions: Respondents from former Soviet republics tend to say their country is more religious today than it was during the 1970s and 1980s. (See Overview for more information.)

In a few countries surveyed that were not Soviet republics – Hungary, Poland, Greece and Croatia – religion appears to have become less important to current adults since childhood. In other countries, there is little difference between the share who say religion is important to them now and the share who say it was important to their family when they were children.

Overall, in all four Catholic-majority countries included in the survey – Poland, Hungary, Croatia and Lithuania – religion seems to have become less important to respondents during the course of their lives. For example, in Lithuania, 58% say religion is either very important or somewhat important in their lives today, compared with 67% who say it was very or somewhat important to their family when they were growing up.

Few adults across the region say they have switched religious traditions

Relatively few adults in Central and Eastern Europe say they have switched their religion from the one they were raised in.

To the extent that there is self-reported religious switching, it has largely bolstered Orthodox populations. In Ukraine, Belarus and Russia, for example, more people currently identify as Orthodox than say they were raised Orthodox. These net gains for Orthodoxy have meant net losses for populations of the religiously unaffiliated; in Russia, 22% of adults say they were not raised in any religion as children, compared with just 15% who say they now consider themselves religiously unaffiliated.

In the Czech Republic, which has the highest unaffiliated share of any country surveyed, the percentage of religiously unaffiliated adults has risen within the lifetime of the survey’s respondents – 64% say they were raised unaffiliated, while 72% are religiously unaffiliated today. The net gains for religiously unaffiliated adults have entailed net losses for Czech Catholics – 29% of Czechs say they were raised Catholic, while 21% are currently Catholic.

Catholics also have experienced a slight loss in Poland: 94% of Polish adults say they were raised Catholic, while 87% currently identify as Catholic. But it is less clear whether, as a result, religiously unaffiliated adults have seen net gains in Poland – 5% of Polish adults say they were raised religiously unaffiliated, or give an unclear response, or refuse to answer the question about how they were raised; 12% of adults say they are currently unaffiliated, give an unclear response, or refuse to answer the question about their current religious identity.

Russians, Ukrainians say religion has become more acceptable in their societies

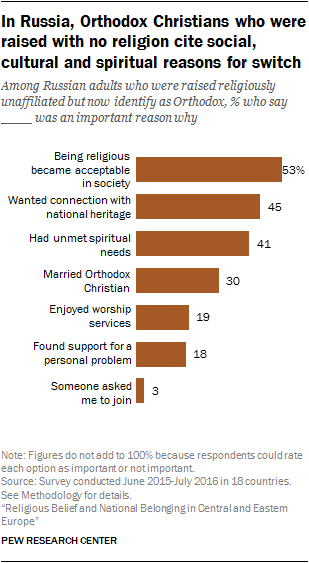

In two countries (Ukraine and Russia) there were adequate sample sizes of adults who currently identify as Orthodox but who say they were raised unaffiliated, allowing for inquiry into why they began identifying with a religion. Respondents were asked about seven potential reasons for their decision to start identifying as Orthodox.

The most commonly cited reason in both countries (by 69% of these respondents in Ukraine and 53% in Russia) was a feeling that religion had become more acceptable in society. This sentiment reflects a change from the Soviet era, when many religious practices were suppressed by the state. Another important reason for beginning to identify as Orthodox, cited by more than four-in-ten of these respondents (48% in Ukraine and 45% in Russia), was to feel a stronger connection to their national heritage.

In Ukraine, a majority (60%) cited marriage to an Orthodox Christian as an important reason they began identifying with Orthodoxy, but this was the case for only 30% in Russia.

Only one country, the Czech Republic, had an adequate sample size of people who say they were raised in a religious group and became unaffiliated as adults.23 The most frequently cited reason for this shift is a gradual drifting away from religion (mentioned by 82% of Czechs who have shed their religious affiliation). Other common reasons for Czechs leaving behind their religious identity are loss of confidence in religious authorities (49%) and no longer believing in religious teachings (45%).

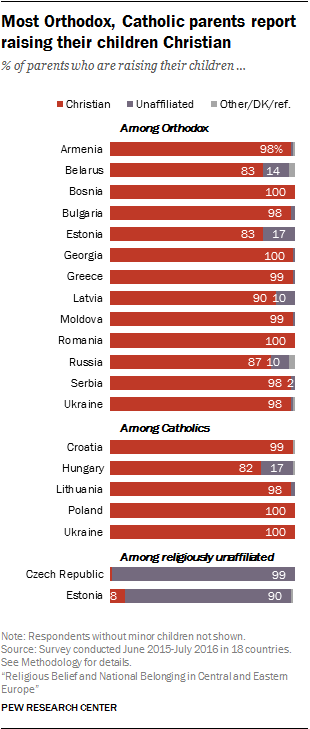

Most parents raising their children with the same religious identity as their own

The survey asked parents of minor children (under 18 years old) how they are raising their children, religiously. Across all countries in the survey, large majorities of parents report that they are raising their children with a religious identity that matches their own.

Among Catholic and Orthodox parents, more than three-in-four say they are raising their children Christian. Roughly nine-in-ten or more Muslim parents say they are raising their children as Muslims, while a similar proportion of religiously unaffiliated parents say they are raising their children without a religion.

(For details on what religious practices parents are implementing into their children’s upbringing, see Chapter 2.)