The differences in religious commitment among subgroups of Israeli Jews are reflected in their religious beliefs and practices, including observance of the Sabbath. For example, virtually all Haredim surveyed say they avoid handling money or riding in a car, train or bus on the Sabbath. Hilonim are much less likely to observe these customs.

Divisions between secular and religious Jews also are seen in many other Jewish beliefs and practices. For example, almost all Haredim – but just three-in-ten Hilonim – say they fasted all day last Yom Kippur.

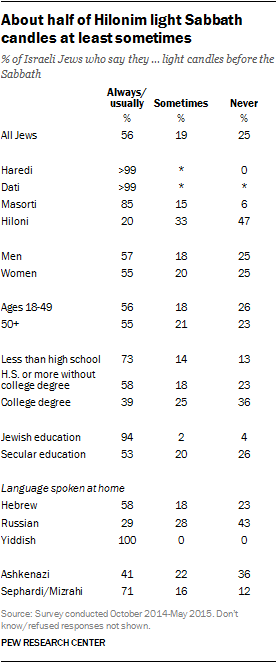

While Hilonim in Israel consistently show lower levels of adherence to Jewish customs and traditions, the survey finds substantial proportions of Hilonim practice some aspects of Judaism, whether for cultural or religious reasons. For example, a large majority of Hilonim say they held or attended a Seder last Passover. Roughly half say they light candles before the start of the Sabbath at least some of the time, including one-in-five who say they usually or always do this. And about one-third of Hilonim say they keep kosher in their home.

Differences in religious observance by gender are also apparent. Overall, Israeli Jewish women are less observant of certain aspects of Jewish traditions than are men. For example, fewer women abstain from traveling on the Sabbath. And fewer women than men say they frequently read religious texts – a pattern seen among Haredim and Datiim as well as among Masortim.

Russian-speaking Jews in Israel stand out for relatively low levels of observance of Jewish beliefs and practices. A majority of Russian speakers say they personally handle money on the Sabbath, for example, and roughly half say they eat pork.

Wide differences in observance of the Sabbath

Haredim and Datiim refrain from handling money on the Sabbath

For observant Jews, handling money is among the activities and behaviors traditionally forbidden on Shabbat (the Jewish Sabbath, which takes place each week from sundown Friday to sundown Saturday). Religious Jews also generally avoid traveling by car, bus or train, operating devices powered by batteries or electricity, igniting or extinguishing a flame, writing, ripping or tearing paper and many other activities prohibited by Jewish law on the day of rest.

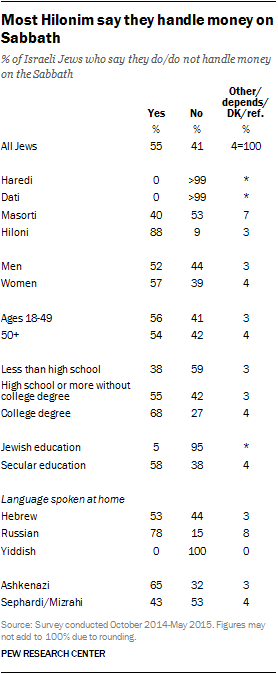

More than half of Israeli Jews say they personally handle money on Shabbat (55%), while 41% say they avoid doing so.

No Haredim and Datiim in the survey say they handle money on the Sabbath, but the vast majority (88%) of Hilonim do. Masortim are more divided on this question.

Among Masortim, observance of this tradition is somewhat more common among men than women. Most Masorti men (58%) say they refrain from handling money on the Sabbath, compared with a somewhat smaller share of Masorti women (48%). There are no significant differences between men and women within the other Jewish subgroups.

Among Jews who received their highest level of education from a religious institution, observance of this Sabbath prohibition is nearly universal. By contrast, among those who completed their education at a secular institution, 58% say they handle money on the Sabbath.

Russian-speaking Jews and Jews of Ashkenazi ancestry are more likely than other Jewish subgroups to say they handle money on Shabbat, a pattern also seen in other areas of religious practice.

Most Israeli Jews – but not Haredim and Datiim – travel by car, bus or train on the Sabbath

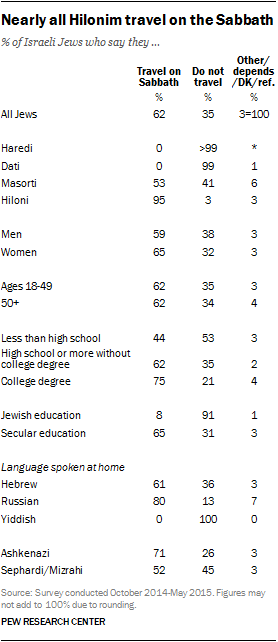

A majority of Jews in Israel say they ride in a car, bus or train on Shabbat (62%), but about a third (35%) say they refrain from traveling on the Jewish holy day.

No Orthodox Jews surveyed travel on the Sabbath, while the vast majority of Hilonim (95%) say they do travel by car, bus or train on the Jewish day of rest.

Masortim are somewhat more apt to say they travel on the Sabbath (53%) than to avoid such activity (41%), while 6% say it depends on the situation.

Women are somewhat more likely than men to say they travel on Shabbat (65% vs. 59%). This gap stems largely from Masortim; women in this group are considerably more likely than men to say they travel on the Sabbath (61% vs. 46%).

Israeli Jews with a college degree are considerably more likely to say they travel on Shabbat than are Jews with less education. And a majority of Jews who earned their highest degree from a secular institution say they travel on the Sabbath (65%), compared with just 8% of those who received their highest education at a religious institution.

As with other aspects of religious observance, Ashkenazim are somewhat less observant by this measure than are Sephardi and Mizrahi Jews.

Slim majority of Israeli Jews always or usually light Sabbath candles

A slim majority of Israeli Jews (56%) say they, or someone in their household, either always or usually lights candles to mark the coming of the Sabbath on Friday evenings. But as with most other measures of religious beliefs and practices, when it comes to lighting Sabbath candles, there are many differences among religious and demographic subgroups.

Lighting candles shortly before Shabbat is a nearly universal practice among Datiim and Haredim. By comparison, one-in-five Hilonim say they always or usually observe this Sabbath ritual in their home, while nearly half of Hilonim (47%) say they never do this.

Jews who speak Hebrew at home are about twice as likely as Russian speakers to regularly observe this ritual (58% vs. 29%). Among those who speak Yiddish at home, every respondent in this survey says that someone in his or her household always or usually lights Sabbath candles.

Comparing religious observance among Jews from the former Soviet Union and their children

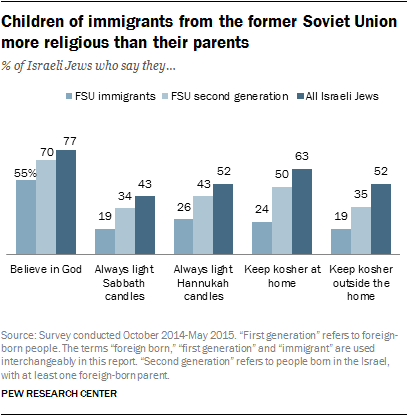

First- and second-generation immigrants from the former Soviet Union (FSU) make up roughly one-fifth of Jewish respondents in the Pew Research Center survey; 14% are immigrants and 5% are children of at least one immigrant parent. Overall, Jews who immigrated to Israel from the former Soviet Union are less religious than Israeli Jews as a whole.

But the survey also finds that second-generation FSU Israelis are considerably more religiously observant than their parents’ generation. When it comes to Jewish subgroups, for example, 60% of those in the second generation say they are Hiloni, compared with 81% of first-generation immigrants. While 4% of first-generation immigrants say they are Haredi, among the second generation, this proportion has climbed to 14%.

Children of FSU immigrants also are much more likely than their parents to believe in God (70% vs. 55%). On this question, second-generation FSU immigrants are closer to Israeli Jews overall, 77% of whom say they believe in God.

Similarly, when it comes to Jewish religious practices such as lighting Sabbath candles, keeping kosher, holding or attending a traditional Seder and studying the Torah, children of FSU immigrants are considerably more active than the first generation. For example, children of FSU immigrants are about twice as likely as their parents to keep kosher, both in their home (50% vs. 24%) and outside their home (35% vs. 19%). And while about four-in-ten first-generation immigrants from the former Soviet Union (42%) say they eat pork, only 17% of second-generation FSU immigrants say they personally do so.

Most Israeli Jews keep kosher in their home and avoid eating pork

Jewish dietary laws, known as kashrut, include several common practices. For example, Jews observing these laws do not eat meat and dairy products together in the same meal, and they do not eat certain types of animal products (including pork and shellfish).

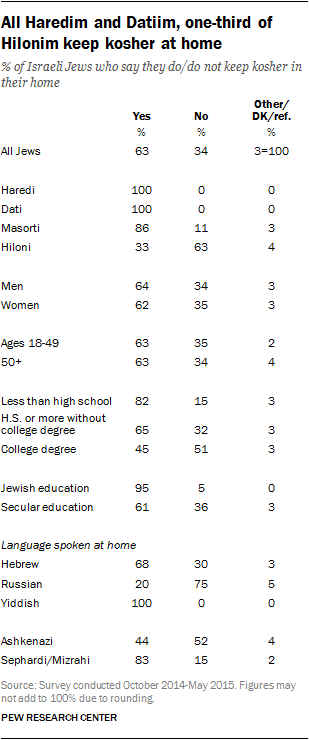

Roughly six-in-ten Israeli Jews say they keep kosher in their home. This practice is virtually universal among Haredim and Datiim and very common among Masortim (86%), but it is less common among Hilonim. A third of Hilonim (33%) say they keep kosher at home, while most (63%) do not.

The secular-religious divide on keeping kosher is also reflected in differences between Jews who received secular or religious instruction. Jews who received their highest level of education from a religious institution are considerably more likely than Jews who earned their highest degree from a secular school to say they keep kosher at home (95% vs. 61%).

There are no significant differences between men and women or between older and younger adults when it comes to keeping kosher at home. Jews with less formal education, however, are more likely than others to keep kosher in their home. Among ethnic and linguistic groups, Sephardi and Mizrahi Jews and Yiddish-speaking Jews are especially likely to report keeping kosher.

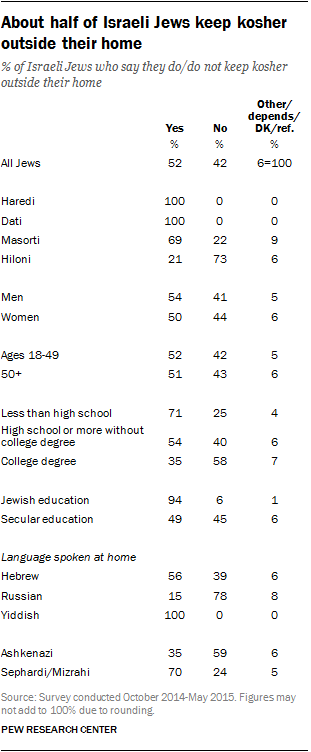

Fewer Israelis say they keep kosher outside their home (52%) than in their home (63%).

All Haredim and Datiim, and most Masortim (69%), in the survey say they observe kosher laws outside their home. Among Hilonim, however, only about one-in-five do so.

As with keeping kosher in the home, there are familiar patterns by ethnicity and education level and type in following Jewish dietary guidelines outside the home. For example, Jews with Sephardi or Mizrahi ancestry are much more likely than Ashkenazi Jews to say they keep kosher outside their home (70% vs. 35%).

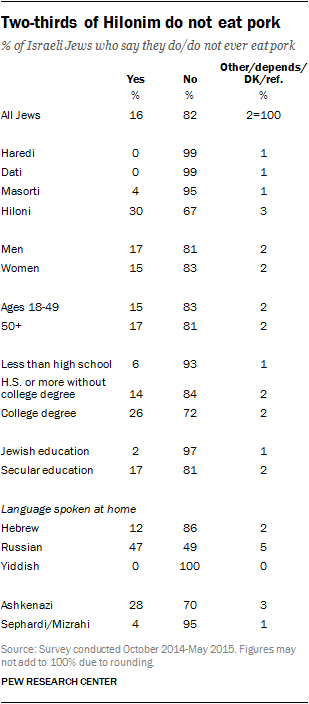

Overall, relatively few Israeli Jews (16%) say they eat pork. An overwhelming majority (82%) do not consume bacon or other pork products, which are not kosher. Even a solid majority of Hilonim (67%) say they refrain from consuming pork.

Russian-speaking Jews are more likely than Israeli Jews overall to eat pork. Roughly equal shares of Jews who speak Russian at home say they eat pork (47%) and refrain from eating pork (49%). No Yiddish speakers interviewed in this survey say they eat pork, and just 12% of Hebrew-speaking Jews in Israel say they, personally, consume pork.

Ashkenazi Jews – one-quarter of whom speak Russian at home – are more likely than Sephardi or Mizrahi Jews to say they eat pork (28% vs. 4%).

Most Israeli Jews light Hanukkah candles

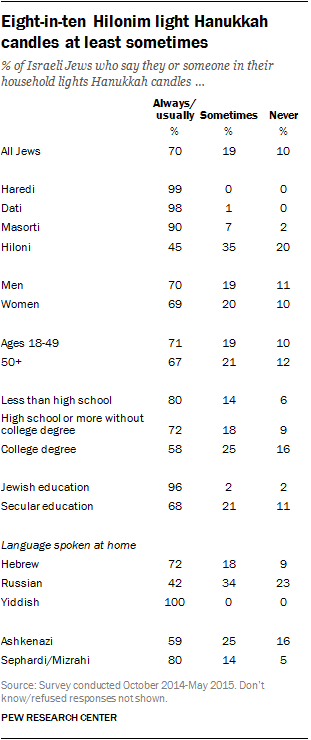

A majority of Jews in Israel (70%) say they always or usually light candles on Hanukkah – the eight-day festival of lights that commemorates the Maccabees’ rededication of the Temple in 165 B.C.E. after its desecration by the Seleucid Greeks. Roughly one-in-five (19%) say they sometimes light Hanukkah candles, while relatively few (10%) never practice this ritual.

Lighting candles for Hanukkah is less common among Hilonim than among other Israeli Jews. Still, even among this nominally secular group, 45% say they always or usually light candles during Hanukkah, and an additional 35% say they sometimes do.

Patterns by primary language, ethnicity and education level and type are similar to other measures of Jewish religious observance. There are no differences by age and gender when it comes to frequency of lighting Hanukkah candles among Israeli Jews.

Attending a Passover Seder among most popular Jewish rituals in Israel

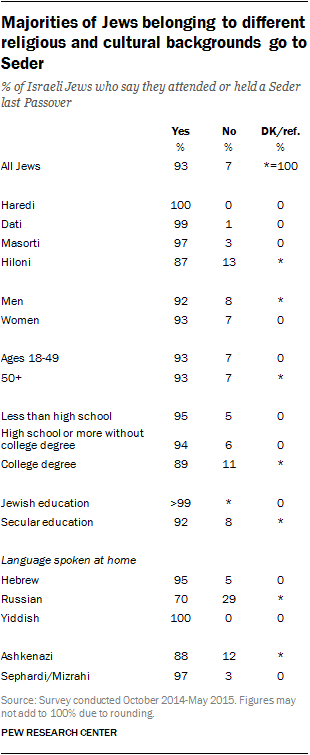

Passover Seders – festive meals with special foods that involve the retelling of the story of ancient Jews’ exodus from slavery in Egypt – are widely popular among Israeli Jews. Roughly nine-in-ten (93%) Jews in Israel say they attended or held a Seder last Passover.

Seder attendance was all but universal among Haredim, Datiim and Masortim; the vast majority of Hilonim (87%) also participated in a Seder.

Even among comparatively less observant Russian-speaking Jews in Israel, seven-in-ten (70%) say they attended or held a Seder last Passover. Nearly nine-in-ten or more among virtually all other demographic groups also did this.

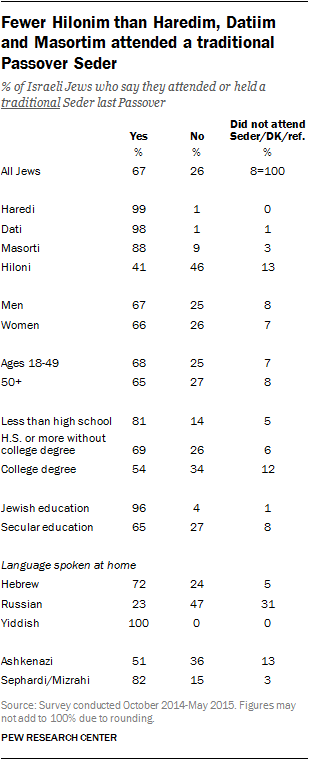

Israeli Jews also were asked if they attended a traditional Seder last Passover. Two-thirds (67%) say they attended a traditional Seder, while about a quarter (26%) say the Seder they attended was not traditional.

Hilonim stand out from other Jews on attendance at a nontraditional Seder; 41% of Hilonim say they attended a traditional Seder, while 46% say the Seder they attended was not traditional. Virtually all Haredim and Datiim and the vast majority of Masortim say they attended a traditional Seder.

Only about a quarter of Russian-speaking Jews (23%) say they attended a traditional Seder last year, while a considerably higher share (47%) attended a nontraditional Passover meal. The vast majority of Sephardi, Mizrahi and Ashkenazi Jews say they attended a Seder of some kind last Passover, but Sephardim and Mizrahim are considerably more likely than Ashkenazim to say the Seder they attended was traditional in nature (82% vs. 51%).

Israeli Jews with lower levels of education – and those who received their highest training from a religious rather than a secular institution– are more likely than others to attend a traditional Seder.

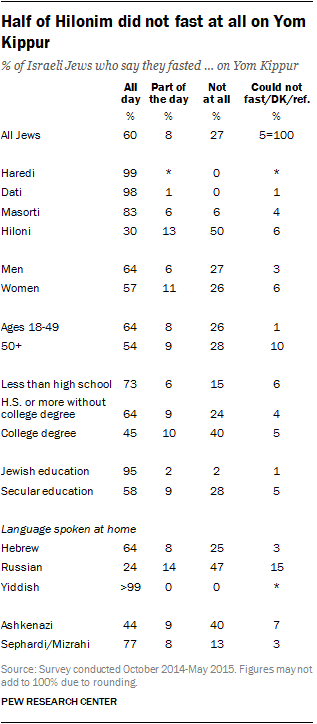

Most Israeli Jews fasted all day last Yom Kippur

Observant Jews who are physically able generally go without food and drink on Yom Kippur – the annual Jewish Day of Atonement and the holiest day on the Jewish calendar, which occurs shortly after Rosh Hashanah (the Jewish New Year). Most Jews in Israel (60%) say they fasted all day last Yom Kippur, while about a quarter did not fast at all and a small proportion (5%) say they were unable to fast for health reasons or did not answer the question.

Among Hilonim, half say they did not fast at all last Yom Kippur, compared with three-in-ten who report fasting all day and roughly one-in-ten (13%) who fasted part of the day.

Fasting during Yom Kippur is nearly universal among Haredim and Datiim. The vast majority of Masortim (83%) also say they fasted all day last Yom Kippur.

Russian-speaking Jews in Israel are more likely than others to say they did not fast at all on Yom Kippur (47%); an additional 15% say they could not fast due to health reasons or did not answer the question.

A majority of Sephardi/Mizrahi Jews say they fasted all day on Yom Kippur (77%), compared with 44% of Ashkenazi Jews.

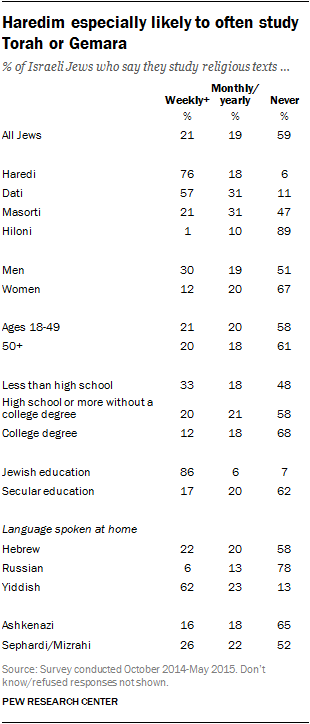

About six-in-ten Israeli Jews never read religious texts

Compared with several other Jewish rituals, fewer Israeli Jews say they read religious texts on a regular basis. Roughly one-in-five Jews (21%) say they read the Torah (the five books of Moses) or Gemara (a religious text with rabbinical analysis and commentary) on a daily or weekly basis, while an additional one-in-five (19%) read these texts on a monthly or yearly basis. A majority of Israeli Jews (59%) say they never read Jewish religious texts.

When it comes to reading religious texts, the difference between Orthodox and non-Orthodox Jews in Israel is large. About three-quarters of Haredim (76%) and a slim majority of Datiim (57%) say they read religious texts on at least a weekly basis, compared with one-in-five Masortim (21%) and very few Hilonim (1%).

Perhaps the largest divide on this issue is connected to the type of education one received. Among Jews who received their highest education from a religious school, 86% say they read religious texts at least weekly, compared with 17% of those who received their highest training from a secular institution.

Men are more likely than women to say they study the Torah or Gemara on a daily or weekly basis (30% vs. 12%). This gender difference is particularly pronounced among Haredim. Roughly eight-in-ten Haredi men (79%) say they read religious texts daily, compared with 27% of Haredi women. Although differences by gender are less pronounced within other groups, Dati and Masorti men also are more likely than women to say they regularly read religious texts.

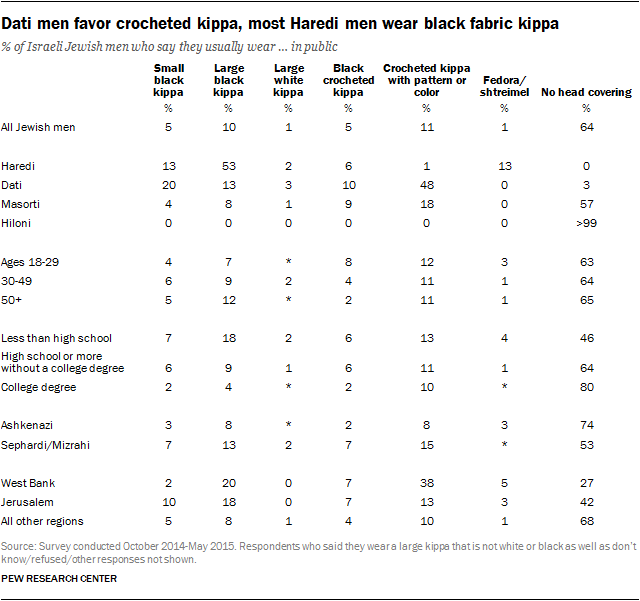

About one-third of Jewish men, one-in-five Jewish women wear a head covering of some kind in public

A majority of Israeli Jewish men (64%) – including virtually all Hiloni men (more than 99%) – say they usually do not wear any head covering in public. However, wearing head coverings, and especially particular kinds of head coverings, is far more common among men of some demographic and cultural backgrounds.

Nearly all Haredi and Dati men say they wear head coverings in public. Among Haredim, roughly half of men (53%) say they wear a large kippa made of black fabric in public, while an additional 13% wear a small black kippa. Some Haredi men also wear a hat, such as a fedora or shtreimel (a fur hat sometimes worn by Hasidic Jews). For Datiim, a crocheted kippa is most common; 48% of Dati men say they usually wear a colored or patterned crocheted kippa, while an additional 10% wear a black crocheted kippa.

A slim majority of Masorti men (57%) say they do not wear any head covering in public, although many wear a crocheted kippa, whether colored or patterned (18%) or black (9%).

Certain head coverings are more common in particular regions of Israel, in large part because of the religious composition of residents. For instance, residents of the West Bank and Jerusalem are considerably more likely than other Israeli Jewish men to say they wear traditional Jewish head coverings in public. And on the West Bank, roughly four-in-ten Jewish men (38%) say they wear a crocheted kippa with patterns or colors.

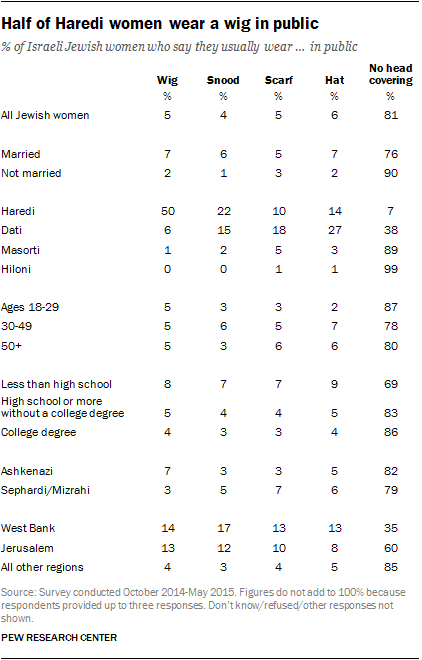

The vast majority of Israeli Jewish women say they do not wear traditional head coverings (81%). Head coverings are much more common among married (25%) than unmarried (9%) women, reflecting Jewish tradition.

Nearly all Hiloni women (99%) and 89% of Masorti women say they do not wear head coverings in public. Overall, about half of Haredi women (married and unmarried) say they wear a wig, while 22% say they wear a snood (which holds the hair in yarn or cloth). Still others wear a hat (14%) or a scarf (10%) over their head. Among Dati women, a smaller share (6%) wear a wig, but most say they wear a head covering of some kind, such as a snood (15%), scarf (18%) or hat (27%).

Virtually all married Haredi women (99%) and most married Dati women (71%) wear some kind of head covering.

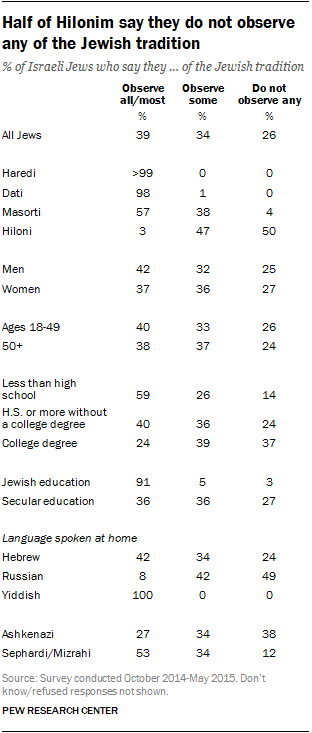

Israeli Jews vary widely in overall observance of Jewish tradition

About four-in-ten Israeli Jews say they observe all or most of the Jewish religious tradition (39%). About a third say they follow some of the tradition (34%), while about a quarter (26%) say they don’t observe any of the Jewish tradition at all.

Nearly all Haredim and Datiim say they observe all or most of the Jewish religious tradition. Meanwhile, very few Hilonim (3%) say they follow all or most of the tradition. Hilonim are about evenly divided between those who follow some Jewish tradition (47%) and none at all (50%).

Masortim hold the middle ground between secular and religious Jews. A slim majority of Masortim (57%) say they observe all or most of the Jewish tradition, while 38% say they observe some of the tradition. Relatively few Masortim (4%) say they observe no Jewish tradition at all.

Among both Orthodox and non-Orthodox Jews, younger adults are about as likely as older Jews to say they observe all or most of the Jewish tradition. Men are somewhat more likely than women to say they observe all traditions (24% vs. 17%), but about as likely to say they observe most traditions (18% vs. 20%).

There are sizable differences in observance by level of education. Jews who have less formal education are more likely than their peers with high school or college degrees to say they observe all or most of the religious tradition. In part, this difference may reflect the fact that Haredim are disproportionally represented among Jews with less than a high school education. Fully 19% of those with less than high school education are Haredi, compared with 9% in the Jewish adult population overall. (See Chapter 7 for more on educational differences among Jewish subgroups.)