Americans are of two minds when they consider scientific advancement. In broad terms, they think scientific and technological innovations are of benefit to society. But when it comes to using particular cutting-edge technologies to potentially augment human abilities – such as allowing parents to edit their baby’s genes for a lifetime of much reduced disease, or offering brain chip implants or synthetic blood substitutes to healthy people who want to perform at higher levels – a new Pew Research Center survey suggests people’s concern rises.

Experts’ take on humanity’s quest to better itself

Pew Research Center conducted interviews with scientists, ethicists and religious leaders about the scientific and ethical dimensions of human enhancement. “Human Enhancement: The Scientific and Ethical Dimensions of Striving For Perfection” summarizes the proponents’ chief arguments, many of whom call themselves transhumanists, and reviews the chief cautions raised by bioethicists and the still-nascent views of major religious traditions as they grapple with the potential of cutting-edge technologies that would change human capabilities.

This chapter explores Americans’ familiarity with, and thoughts about, several techniques on the vanguard of science that could be used to expand the limits of people’s bodies and brains. It examines the patterns that run across public opinion on the three case studies, including the large differences in acceptance between highly religious and less religious Americans; the tendency of people to be more open to these technologies if their effects would be controllable and less dramatic in magnitude; the gender gap in opinions on this topic, with women more wary than men about these developments; and the links between views toward enhancements widely available today, such as cosmetic surgery or laser eye surgery; and views toward potential future enhancements.

Most Americans not interested in improving their cognitive or physical abilities with brain chips or synthetic blood

Converging technologies in biomedical, nanotechnology, information technology and other fields could lead to any number of ways humanity might be able to “upgrade” itself. The Pew Research Center study focuses on the U.S. public’s reactions to three particular kinds of technologies that could be used in the relatively near-term for human enhancement: gene editing to give a healthy baby a much reduced risk of serious diseases and conditions over their lifetime; implanting a computer chip in the brain to give a healthy person a much improved ability to concentrate and process information; and a transfusion with synthetic blood to give healthy people much improved speed, strength and stamina.

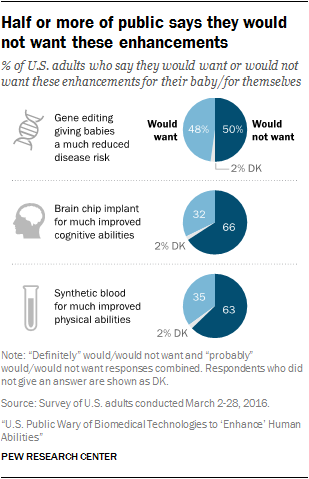

Overall, none of the three enhancements are particularly appealing to the general public. Altogether, 50% of Americans say they would not want gene editing to significantly reduce their own baby’s risk of serious diseases and conditions. A roughly equal share of adults (48%) say they would probably or definitely want this for their baby.

U.S. adults are even less eager to get a brain chip implant or synthetic blood. Roughly two-thirds of Americans (66%) say they would not be interested in an implanted device designed to give them a much improved ability to concentrate and process information; a third (32%) say they would definitely or probably want such a device. The same pattern occurs when it comes to a synthetic blood substitute for much greater speed, strength and stamina. Most Americans (63%) say they would not want this, while 35% say they would definitely or probably want it.

Gene editing to improve a baby’s health appears more appealing to the public as a whole than the other two scenarios. This difference could stem from the fact that the gene-editing scenario is focused on disease-prevention, while the other two scenarios are more about augmenting abilities. Another possibility is that public thinking about genetic interventions that would enhance their children’s characteristics involves different calculations than changes to better themselves. Still, there are striking similarities detailed below in how Americans evaluate the likely outcomes and moral acceptability of all three of these potential enhancements.

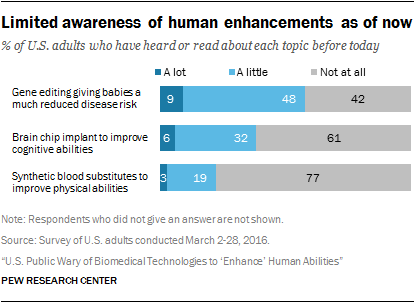

Some have heard about these ideas, especially gene editing, but few have heard a lot

As might be expected when it comes to future possibilities, few Americans report deep familiarity with gene editing, chip implants or synthetic blood substitutes. But 48% of adults say they have heard a little about the idea of gene editing for babies and another 9% say they have heard a lot. Nearly four-in-ten adults have heard either a lot (6%) or a little (32%) about brain chip implants. The idea of synthetic blood substitutes to boost physical speed, strength and stamina is less familiar, by comparison; 77% of Americans have heard nothing at all about this possibility.

Those who have heard at least a little about these ideas are more inclined to want these enhancements for themselves (or, in the case of gene editing, for their baby). While greater familiarity with these ideas could be driving more desire for these enhancements, at this early stage, it could be simply that people who are predisposed to favor new technologies seek out information about new technological developments and also tend to favor these possibilities.

A similar pattern was found in a 2013 Pew Research Center study on radical life extension. Those who had heard more about this idea were more likely to say they would want medical treatments to slow the aging process and extend average lifespans by decades.

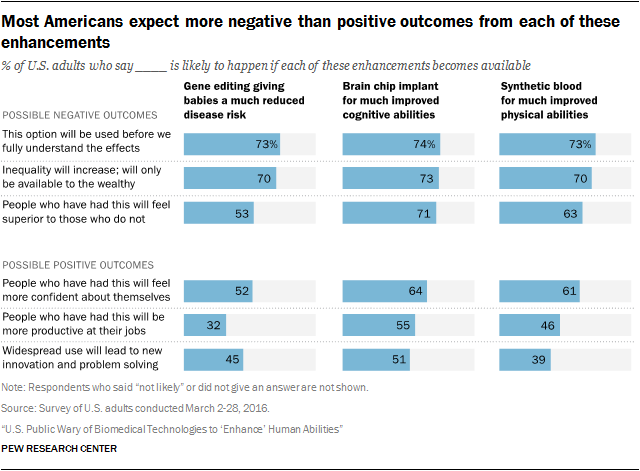

Most Americans see human enhancements causing major changes ahead, but more expect negative rather than positive effects

There is widespread agreement among the public that if the enhancements considered in the survey become widely available for healthy people, change will follow. But significantly more Americans expect negative outcomes, including premature adoption of techniques that are not well tested and increased social inequality.

Focus groups raise the potential for unexpected consequences

Focus group participants mentioned a number of ideas about how these kinds of enhancements could affect people’s personalities, family relationships, health and performance on the job, as well as intergroup relations in society as a whole.

Among the points raised were concerns about potential misuse of enhancements, especially by people with criminal intent. Others mentioned a general concern that implanted devices could become obsolete without an “upgrade.” Similar concerns were raised about using synthetic blood substitutes and gene-editing techniques. See “American Voices on Ways Human Enhancement Could Shape Our Future.”

Some 81% of adults say gene editing that would give babies a much reduced risk of serious diseases over their lifetime would cause either a great deal of change for society (46%) or some change (35%). A similar share – 79% – say an implanted brain chip giving healthy people a much improved ability to concentrate and process information would lead to at least some change. And 76% of adults say transfusions of synthetic blood to give healthy people much improved physical abilities would cause a great deal of change (38%) or some change (38%) for society.

In terms of the potential outcomes of adopting these techniques, more Americans anticipate negative rather than positive consequences. At the top, at least seven-in-ten adults are concerned that these new technologies will become available before they have been fully tested or understood. This concern was echoed in the focus group discussions, particularly in connection with brain chip implants.

Another mark on the minus side of the chart: Many Americans think these developments could exacerbate the divide between the haves and have-nots in society. Some seven-in-ten survey respondents say inequality would increase because only the wealthy could afford these enhancements.

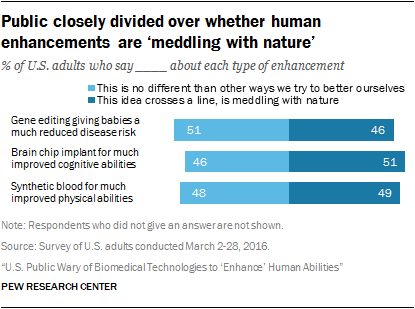

Jury is still out on moral acceptability: Are humans bettering themselves or meddling with nature?

Americans are closely divided on the key ethical question of whether gene editing, brain chip implants, or synthetic blood substitutes are just another step in a long line of efforts humans have made over time to better themselves, or if, instead, these ideas are “meddling with nature” and, as such, cross the bounds of what humans should do. In each case, the public is nearly evenly divided between the two perspectives.

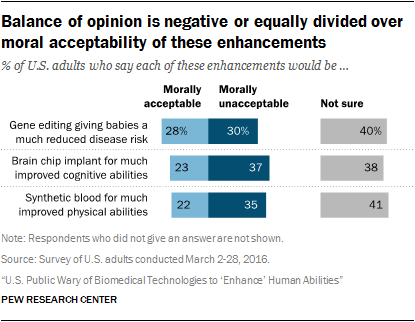

When it comes to moral evaluations of these potential human enhancements, there also are wide differences among the public as a whole. A sizeable portion of the public says they are “not sure” whether these three possible enhancements are morally acceptable. Among the remainder, the balance of opinion is closely divided over whether gene editing that would give babies a much reduced risk of disease is morally acceptable (28%) or unacceptable (30%). The balance of opinion leans negative for brain chip implants (23% say this is morally acceptable and 37% say it is unacceptable) and synthetic blood (22% vs. 35%).

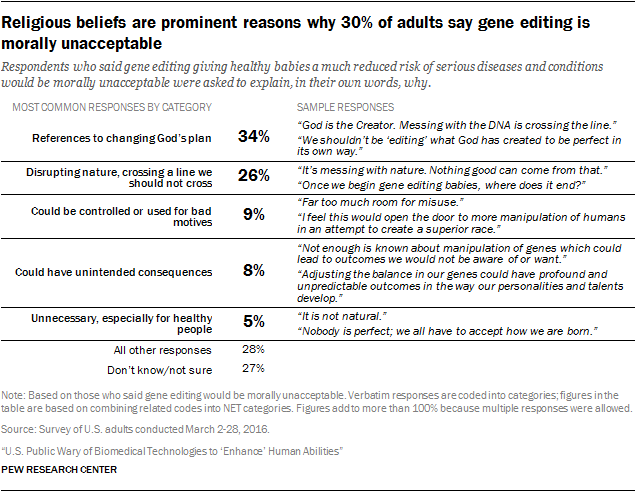

Asked to explain their reasons, many of those who said gene editing to give babies reduced risk of disease is morally unacceptable raised concerns that this “interferes with God’s plan” or is “messing with nature.”

On the other hand, some of those who say gene editing is morally acceptable reasoned that gene editing was similar to other kinds of medical advances and improvements society has made over time or that these emerging technologies will have positive effects for society.

Similar themes emerge when it comes to the moral acceptability of brain chip implants or synthetic blood substitutes. In thinking about moral objections to the possibility of brain chip implants, some respondents made explicit mentions of religion, especially concerning the similarity of this idea to the “mark of the beast” as foretold in the Bible’s book of Revelation.

Key patterns in Americans’ attitudes about human enhancements

Beyond these readings of overall opinion, several consistent patterns in people’s views about these human enhancements stand out. First, people’s opinions across all three scenarios are strongly connected with their religiosity. More religious Americans are, on average, less likely to embrace these potential types of human enhancement. This stands in contrast to more modest differences by religious affiliation and frequency of religious service attendance in the 2013 Pew Research Center report which explored public views about another form of human enhancement: radical life extension. And, a 2014 Pew Research Center survey found only a handful of issues where people’s religious beliefs and practices have a strong connection to their views about a range of science-related issues.

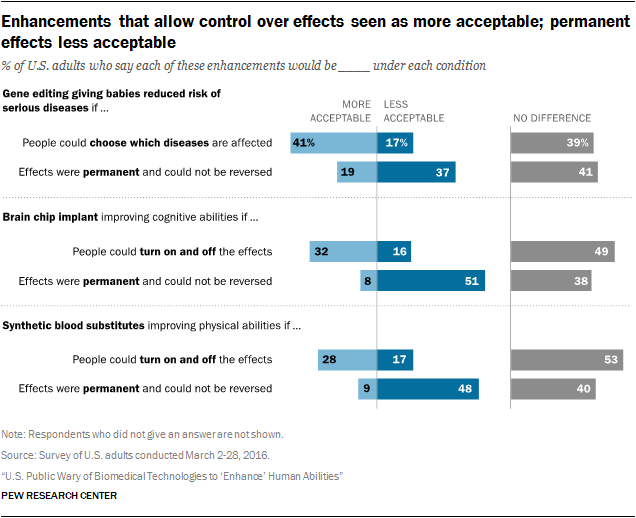

A second consistent pattern is that people are less accepting of enhancements that produce extreme changes in human abilities. And, if an enhancement is permanent and cannot be undone, people are less inclined to support it.

And, third, one demographic pattern stands out: Women are consistently more wary than men about these potential enhancements. At the same time, there are few differences in opinion across racial and ethnic groups, education and income levels, or age groups.

As a point of comparison, this study also examined public thinking about a handful of enhancements widely available today, including elective cosmetic surgery, laser eye surgery, skin or lip injections, cosmetic dental procedures to improve one’s smile, hair replacement surgery and vasectomy or tubal ligation procedures to prevent pregnancy. There is a similar strain to public views about current enhancement practices in that most Americans say “people are too quick to undergo cosmetic procedures in order to change their appearance in ways that are not really important.” And, when it comes to evaluations of elective cosmetic surgery, in particular, more say the downsides outnumber benefits for society than vice versa; about half of Americans say the benefits and downsides equal out. The next part of this report goes through those patterns in more detail.

Pattern 1: Public views are strongly connected with religious differences; the more religious are most negative while the least religious are most positive

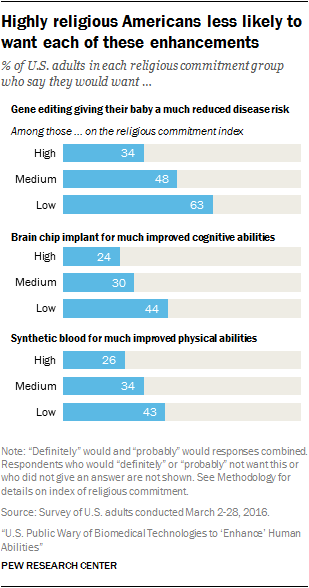

People’s views about human enhancements are strongly linked with their religiosity. The Center created an index of three common measures of religious commitment – how people describe the importance of religion in their lives, how often they attend worship services and how often they pray7 Across all three human enhancement scenarios, the highly religious are much less positive about these human enhancements. Those who are less religious, by comparison, are much more likely to want each of these enhancements, to see them as akin to other ways humans have tried to better themselves and, on balance, to see them as morally acceptable and likely to bring more positives than negatives to society if implemented.

Some 63% of those with low religious commitment say they would want gene editing for their baby to reduce the risk of serious diseases and conditions. Just 34% of the most religious say the same, a difference of 29 percentage points. A similar pattern occurs when it comes to desire for an implanted device to dramatically improve one’s concentration and ability to process information; 44% of those low in religious commitment would want this, compared with 24% of those high in religious commitment. The figures are roughly the same in reaction to getting a transfusion with synthetic blood substitutes to dramatically improve one’s speed, strength and stamina.

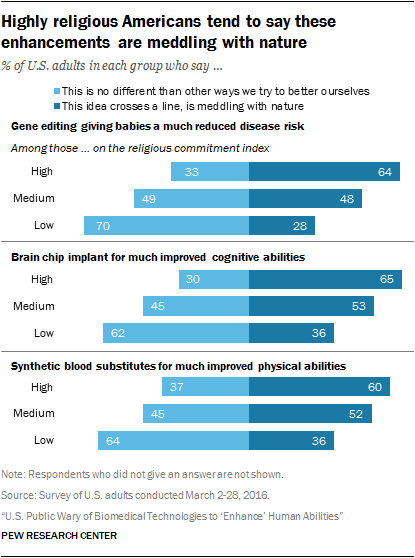

More religious adults are more likely to assess each of these human enhancements as “meddling with nature,” crossing a line that should not be crossed. Six-in-ten or more of those high in religious commitment say this about gene editing to give babies a reduced risk of serious disease, brain chip implants to improve cognitive function and synthetic blood substitutes to improve physical abilities. By contrast, majorities of those low in religious commitment say each of these enhancements would be no different from other ways humans try to better themselves.

Differences by religiosity remain strong and significant even when taking into account other factors that tend to be related to religious commitment in modern America, such as gender, race and ethnicity, age and education. To give one example, when statistically controlling for other factors, those high in religious commitment are, on average, 32% more likely than those low in religious commitment to say gene editing that would give babies a much reduced risk of serious diseases is meddling with nature8

There are similarly strong differences by religious commitment levels in moral judgments about these enhancements. While a sizable minority says they are not sure about the moral acceptability of these enhancements, those high in religious commitment are more likely to say each of these ideas is morally unacceptable rather than acceptable by a ratio of about 2.5-to-1. But, the balance of opinion goes in the opposite direction among those low on the religious commitment index.

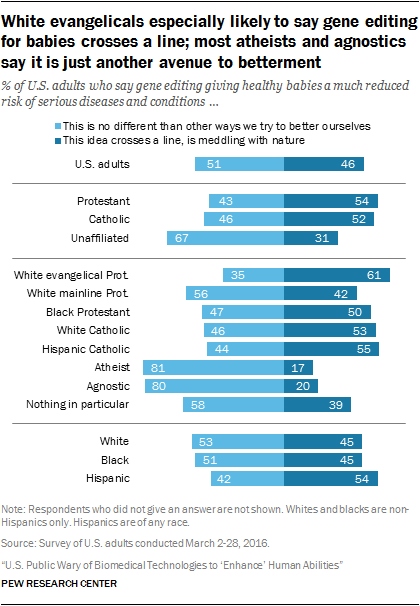

There also are substantial differences by religious affiliation in views about human enhancements. For example, 61% of white evangelical Protestants say gene editing that would give babies a much reduced risk of serious diseases would be meddling with nature, compared with half as many people with no religious affiliation who say this (31%).

Self-described atheists and agnostics, in particular, stand out from other religious groups on this question. Strong majorities of atheists (81%) and agnostics (80%) say gene editing to give healthy babies a much reduced chance of disease is similar to other ways humans have tried to better themselves over the years.

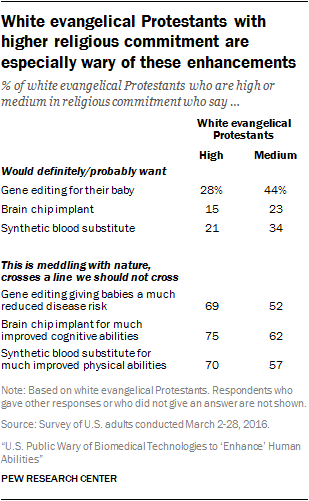

Negative reactions to human enhancement are particularly strong among the most committed white evangelical Protestants

In comparison with most other religious groups, white evangelical Protestants are less likely to want these enhancements and more likely to express reservations about these possible developments.

Reservations are particularly common among white evangelicals who are higher in religious commitment – that is, those who say religion is very important in their life, attend religious services at least weekly and engage in prayer every day.

For example, 28% of highly religious white evangelical Protestants say they would want gene editing for their baby, compared with 41% of white evangelicals with medium levels of commitment and 48% of the general public.

And, white evangelical Protestants who are highly religious are more inclined than those with a medium level of commitment to consider each of these enhancements as “meddling with nature” and crossing a line that should not be crossed. Some 69% of highly committed white evangelicals say this about gene editing, compared with 52% among those with a medium level of commitment.

Pattern 2: Enhancements that produce more extreme or permanent effects are seen as less acceptable

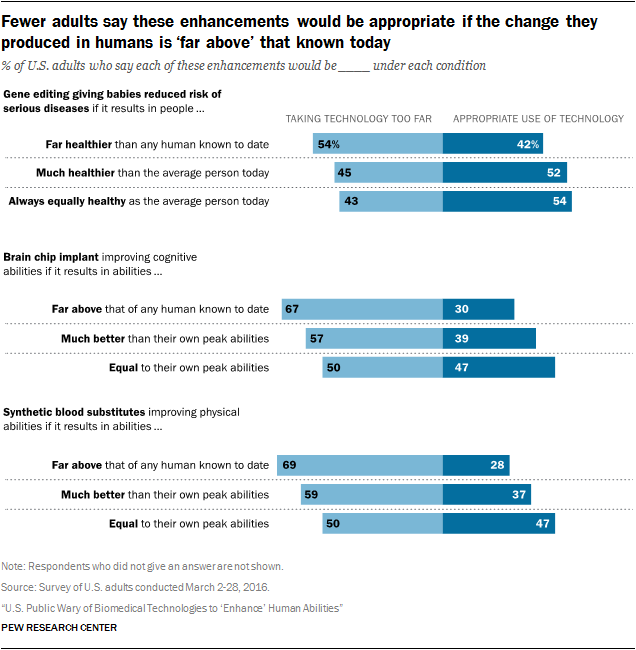

Public views about human enhancements are linked with the magnitude of change such enhancements are expected to bring as well as with their permanence. When considering an enhancement with more extreme effects – a change that would help a person operate “far above” their current abilities – fewer people say the enhancement would be an appropriate use of technology.

For example, only 28% of adults say a synthetic blood substitute would be an appropriate use of technology if it produced improvements to speed, strength and stamina that were “far above that of any human known to date.” By contrast, some 47% of adults say synthetic blood products would be appropriate if the magnitude of change was much smaller. In this case, that might mean a synthetic blood transfusion that helped a person reach their own peak abilities for speed, strength and stamina, rather than helping a person surpass their best efforts in the past.

In addition, people’s reactions to human enhancements are more positive if the effects are controllable or temporary. For example, 32% of adults say if the implanted devices giving people better concentration and cognitive processing abilities could be “turned on and off” they would be more acceptable. Far fewer adults (16%) say the ability to control the effects of an implanted device would make this idea less acceptable.

In thinking about a scenario in which the effects of a brain chip would be permanent and irreversible, about half of Americans (51%) say this would make the technology less acceptable to them. Only 8% say this would make it more acceptable.

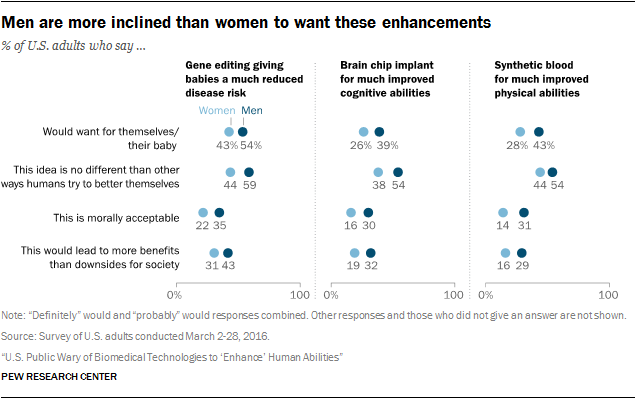

Pattern 3: Women are consistently more wary than men about these potential enhancements

Men are more inclined than women to respond positively to each of the three kinds of human enhancement considered in the survey. Specifically, men are more likely than women to say they would probably or definitely want gene editing to give their baby a much reduced risk of serious disease, an implanted device to improve their concentration and information processing abilities or synthetic blood substitutes to improve their speed, strength and stamina.

Women are less inclined than men to consider each of these enhancements similar to other ways humans try to improve themselves. To give one example, some 54% of men (compared with 38% of women) say implanting devices in the brain to give healthy people a much improved ability to concentrate and process information is akin to other ways humans try to better themselves. Additionally, more women than men say such devices would be meddling with nature and crossing a line that should not be crossed.

While men and women are about equally likely to expect at least some change for society from each of these enhancements, men, more than women, say each of these enhancements would bring net benefits for society.9

The way people think about today’s enhancements, for example cosmetic surgery, has some similarity to the way they think about tomorrow’s potential enhancements

One factor in public reactions to these kinds of human enhancements could well stem from the fact that each is, as yet, only available in very limited circumstances and each is largely unfamiliar to the general public.

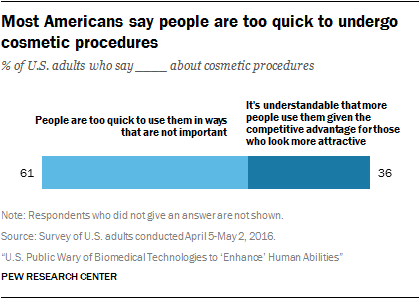

For comparison, the survey included a series of questions about “enhancing” procedures widely available today.10 The results suggest that most people accept modern cosmetic enhancements, even as they believe Americans are too quick to adopt these changes.

Overall, a majority of Americans (61%) say “people are too quick to undergo cosmetic procedures in order to change their appearance in ways that are not really important,” while 36% said “it’s understandable that more people undergo cosmetic procedures these days because it’s a competitive world and people who look more attractive tend to have an advantage.”

As is the case in views about the three more cutting-edge enhancements considered in this project, public views about cosmetic procedures generally tend to differ by religious commitment, although these differences are not as stark.

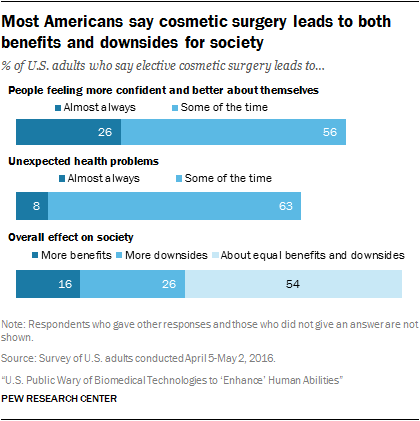

The survey asked for judgments about six specific kinds of procedures widely available today including elective cosmetic surgery, laser eye surgery, skin or lip injections, cosmetic dental procedures to improve one’s smile, hair replacement surgery and vasectomy or tubal ligation procedures to prevent pregnancy. Each of the six was judged to be an “appropriate use of technology” among half or more of the general population. Overwhelming majorities say laser eye surgery (89%) and cosmetic dental procedures to improve one’s smile (86%) are appropriate uses of technology. Smaller majorities say this about elective cosmetic surgery (62%) and skin or lip fillers (53%).

Public opinion about elective cosmetic surgery has a negative tinge: More judge the overall benefits of such surgery for society to be negative than positive (26% compared with 16%), even as a 54% majority says the net effects of cosmetic surgery on society are a wash.

Public judgments about potential effects for those who undergo cosmetic surgery are mixed. Some 26% of adults say those who have elective cosmetic surgery almost always “feel more confident and better about themselves.” While several focus group participants worried that future enhancements would result in unexpected side effects, just 8% of the general public says cosmetic surgery “almost always” leads to unexpected health problems; 63% say it sometimes does.

Understandably, the 4% of U.S. adults who say they themselves have had some kind of elective cosmetic surgery hold more positive views about it. And, people who tend to see the kinds of procedures widely available today in a negative light, saying, for example, that people are too quick to undergo cosmetic procedures that are not really important, are more wary about human enhancement from gene editing, brain chip implants or synthetic blood substitute.

Minimal differences by income, education on future enhancements, but there are more divides when it comes to enhancements widely available today

When it comes to the cutting-edge human enhancements considered in this report, there are surprisingly few differences in assessments across class lines: Neither education nor family income is a strong predictor of views. This is despite the fact that the most adults see future social inequality tied to unequal access to these human enhancements.

Those with higher family incomes are, however, more likely to have had one of six kinds of enhancements widely available today (e.g., laser eye surgery to enhance one’s vision or elective cosmetic surgery). And adults with middle- and higher-family incomes are more likely than those with lower incomes to say each of these six kinds of procedures available today is an appropriate use of technology. The same pattern occurs by education level, with college graduates more likely than those with a high school diploma or less schooling to say each of these procedures is an appropriate use of technology.

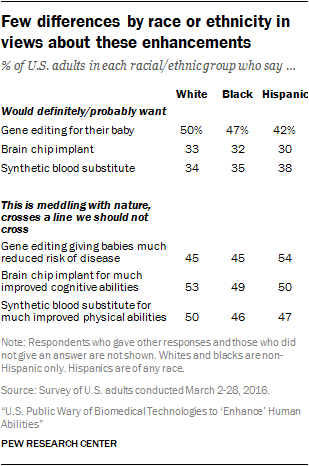

Similar reactions to future human enhancements among white, blacks and Hispanics

There are few differences in views about these cutting-edge human enhancements among whites, blacks and Hispanics. People in these three groups are about equally likely to say they would definitely or probably want gene editing for their baby, an implanted device for themselves or synthetic blood substitutes for themselves. And whites, blacks and Hispanics assess the potential benefits and downsides for society in similar ways.

Hispanics are a bit more likely than whites to consider gene editing for babies to be meddling with nature (54% of Hispanics say this, compared with 45% of whites). The share of blacks who say this (45%) is not statistically different than the shares of whites or Hispanics.

The similarity in views across racial and ethnic groups stands in contrast to views about a different kind of enhancement: radical life extension. A 2013 Pew Research Center survey on the idea of medical treatments that could potentially slow the aging process and extend the average person’s life expectancy by decades found blacks and Hispanics more likely than whites to say radical life extension would be a good thing for society. Blacks and Hispanics were also somewhat more likely than whites to say they would want life-extending treatments.

While this new study finds a number of similarities in judgments about these three types of enhancement, it is useful to remember that different patterns may emerge about other kinds of human enhancement.

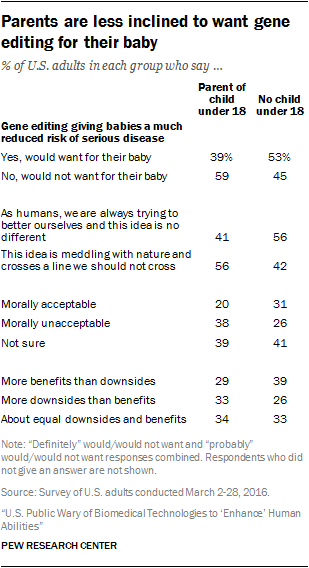

Parents of minor children are more reluctant about gene editing for babies

Parents of minor-aged children are more hesitant than others about gene editing for babies. Parents are less inclined than others to say they would want gene editing for their babies to reduce the risk of serious diseases; they are more likely to consider this idea meddling with nature, to see it as morally unacceptable and to judge that it would bring more downsides than benefits for society as a whole.

While most parents fall within the middle age groups (ages 30 to 64), there are no more than modest generational divides over gene editing. And, views among adults by age differ only modestly, if at all, about using gene editing to improve the health and abilities of the healthy, when controlling for those who have minor age children.

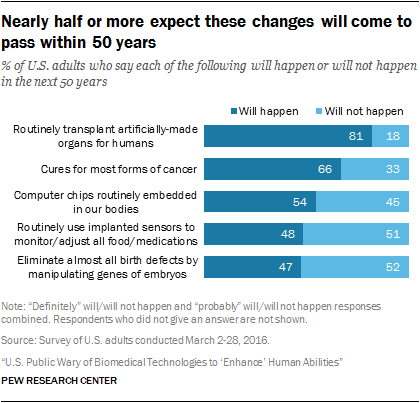

Is change inevitable?

Whether or not the public generally wants human enhancements, most expect changes along these lines to occur within the next 50 years. Medical science is now only occasionally using artificially made human organs for transplants. As Americans consider the future, fully 81% expect such organs to be routinely available for transplant by the year 2066. Roughly two-thirds (66%) of Americans say scientists will probably or definitely cure most forms of cancer by the year 2066.

When it comes to ideas closely linked with the three enhancements that anchor this survey, roughly half of adults (54%) think the idea of implanted computer chips is likely to be a routine occurrence in the future. Some 48% say humans will definitely or probably use implanted sensors to monitor or adjust all food and medications that enter the bloodstream by the year 2066. And a similar share of adults, 47%, foresees a future with almost no birth defects because of genetic modification of embryos prior to birth.