Message in a Bottle

In the two weeks following the 2002 general election, the Institute for Politics, Democracy, & the Internet conducted interviews with campaign staff from 33 of the most hotly contested races for governor, U.S. Senator, and U.S. Representative. We wanted to learn about the Internet’s utility as a campaign tool from campaign professionals with areas of responsibility beyond the Internet. Our respondents consisted primarily of campaign managers, communication directors, and their deputies. We also conducted seven supplemental interviews with campaign Web masters.

Our interview subjects worked under intense pressure in a shifting, often opaque, and always ambiguous information environment. It was their job to obtain and deploy campaign personnel, messages, and money with increasing speed and power until Election Day. “Momentum” is a common term in the campaign world for a good reason: in campaigns, as in physics, force equals mass (of supporters) times acceleration (of visible messages, which cost money). The brief history of online politics is highlighted by campaigns –Jesse Ventura, Moveon.org, John McCain, Roh Moo-Hyun (in South Korea)—which used the Internet to go into turbo drive. Could others repeat their success? Who tried, how well, to what result?

The 2002 hot races that we looked at lacked the charismatic personalities, first-time news appeal, and historical dimensions of the three online campaigns just mentioned. Nevertheless, our races took place on a bigger stage than their state and district jurisdictions suggest. Because control of the House and Senate hung in the balance, these tight contests attracted the attention and involvement of the White House, national political parties, PACs, political journalists, and active citizens everywhere. The Internet facilitated the nationalization of these races. It made it a snap (or click) to keep track of dozens of election contests across the country, and, if one was so inclined, to donate money to a handful of them at the right moments. We sought to learn who among our subjects took advantage of the citizens’ new capability, and multiplied the force of their campaigns by infusing them with online national resources.

What Worked and What Didn’t in Online Campaigning

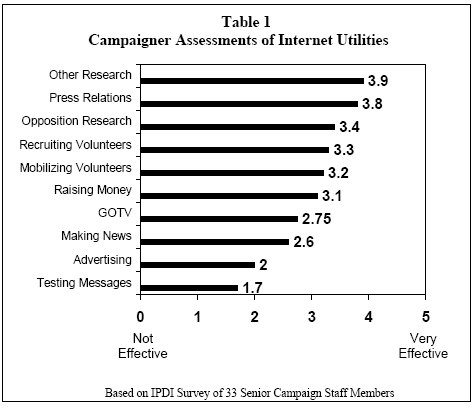

The heart of our November 2002 survey was a series of ten questions about the effectiveness of the Internet in facilitating key campaign functions. We asked campaigners to rate Internet effectiveness by function on a scale of 1-5, where 1 is not effective and 5 is very effective. The results appear in Table 1.

Our campaign professionals found the Internet most effective for conducting research and communicating with the press. These results were not a surprise. Most professionals in all walks of life now head to the Web for research, and rely on e-mail for day-to-day communications. Last year, an IPDI study of political journalists found, for example, that even Net novices rely on it for news releases and campaign finance information.6

At the other end of the scale, the Internet functions that garnered the poorest ratings were advertising and message testing. We were somewhat surprised at the low aggregate rating, and low number of responses, regarding online advertising. Despite the concerted efforts of online media outlets and advertising agencies, online campaign advertising appears to be stuck in neutral. We can identify several factors inhibiting campaigners from placing ads on the Internet: a counter-reaction to the Net hype of the late 1990s; an absence of clear ad-buying procedures, prices, and success benchmarks; and the technical difficulties and ethical questions bound up in targeting voters for a given locality.7 Still, online advertising is inexpensive to produce and place (in part because of the dot-com crash). We thought more campaigns would have experimented with it, and had more to say about it.

Testing messages was not part of the close-race campaigners’ repertoire, either. It takes some effort and know-how to test a message online before a targeted audience, if scientific and nuanced feedback is the goal. However, we know from our national survey that the online citizenry enjoys participating in polls (See Part Two). In 2001, the Mark Earley for Governor campaign in Virginia posted an endorsement video featuring Rudy Giuliani, and the positive response encouraged the Republicans to re-shoot the spot and purchase television time for it. The next, logical step, we think, will be for campaigns to post television ads, speeches, written appeals, and other messages, ask online supporters to evaluate them –and then ask them for contributions to pay for wider distribution of the ones they like.

No clear pattern emerged regarding the use of the Internet to recruit and mobilize campaign volunteers. The respondent from the campaign reporting the largest number of online volunteers (2000, for Janet Napolitano, a successful Democratic gubernatorial candidate in Arizona) gave weak ratings of 3 for recruitment and 2 for mobilization. A representative from another successful gubernatorial candidate, incumbent Democrat Gray Davis of California, reported only “several dozen” volunteers, yet rated mobilization effectiveness at 4. We expected more consistent answers, such as the one we received from Connie Morella’s unsuccessful effort to retain a Republican Congressional seat in a highly wired Maryland district. Her staffer said they found 250-300 volunteers online, and awarded the highest possible ratings (5) for both recruitment and mobilization. Our open-ended questions also elicited comments about the Internet and volunteers which were all over the map. We believe the best way to summarize the situation is that while a majority of campaigns recognized how valuable the Internet can be with respect to volunteers, some campaigns did not know what to expect, or how to proceed.

Fundraising received a slightly lower effectiveness rating from our respondents than volunteer recruitment and mobilization. Again, the scattered pattern of ratings and comments points as much to an absence of accepted standards in expectations and procedures as to poor outcomes. Most online campaigners we have spoken with, both for this report and other IPDI research, have made back in contributions what they have spent on fundraising. Solid majorities of campaign Web sites in races for Congress in 2000 and 2002 posted information about how to make donations. Slender majorities provided the technical wherewithal to make contributions through the Internet.8 We do not know how many 2002 campaigns were as sophisticated with online fundraising as they generally are in direct mail, telephone fundraising, and at events, which is to ask point-blank for a specific amount of money. (In fundraising jargon, this is known as “the ask.”) On the Internet, many such asks would have occurred via e-mail, which was beyond the scope of our study. It was not possible for us to discern whether more candidates even bothered to ask for money on the Web page where they posted their contribution forms; in 2000, as an earlier report of ours showed, a scant 3% of House candidates did so.

There were a few fundraising breakthroughs. The deputy campaign director for victorious Senate candidate Mark Pryor in Arkansas said the campaign Web site “paid for itself a hundred times over,” in the money raised and the way the press paid attention to it. Candidate Martha Fuller Clark, in a losing campaign for a Congressional seat in New Hampshire, raised 30% of her individual contributions online, roughly half a million dollars according to FEC data.

Very few campaigns –four, to be precise—said they received online assistance from their national parties. This stunned us. To the extent that any of the tight races were “nationalized,” this seems to have been accomplished largely through old media and modes of transportation, instead of through the Internet. In the future, we expect parties (and other politically interested organizations with nationwide memberships) to move beyond electronic funds transfers and bus caravans, and integrate the Internet into their efforts on behalf of candidates in close races.

To be sure, such outside online help will be circumscribed. Political organizations are understandably reluctant to share their lists of donors and volunteers. For one thing, the new campaign finance reform law may deter the development of online collaboration, until what is legal and what is criminal in the category of coordinated activities has been thoroughly clarified. For another, there is the problem of list dilution. As soon as a list of names is released to anyone, it can rocket around the Internet, and the originating organization may discover to its chagrin that its capacity to summon help has been considerably reduced. Still, parties, corporations, unions, and groups can protect themselves by sending messages on a candidate’s behalf which urge recipients to click over to the candidate’s site. We heard nothing to that effect from our respondents.

The lack of party assistance helps explain why using the Internet to get out the vote received a sub-medium rating from the campaigners. The 2002 campaigners we spoke with were evidently unimpressed by the success of the Gore campaign in 2000 with its late multi-state ad buy, the NAACP’s real-time coordination of its resources on Election Day, and the Bush campaign’s use of the Net during the Florida controversy. Perhaps they did not know enough about these operations. A few did, however. Illinois gubernatorial candidate Rod Blagojevich deployed a highly sophisticated multi-channel GOTV operation, utilizing the Web, email, and wireless text messaging, to win the Democratic primary in the spring of 2002.9 The Mike Huckabee campaign to retain the Arkansas governorship unleashed a late e-mail blitz which helped Huckabee win even as his co-Republican Tim Hutchinson was losing to the aforementioned Mark Pryor.10

The most discouraging results of our questionnaire dealt with the immediate future. Respondents split evenly on whether they would put more effort into their Web site next time around: 51% said they would (a socially respectable answer to questioners from an Online Politics Institute), while 45% would not. Most said they noticed a proliferation of campaign Web sites, and of sophistication in their use. Yet most respondents could not cite an online campaign that impressed them, a sign that they saw no external incentives to improve.

Finally, we learned more about online campaigning, and about email lists in particular, from our separate post-election interviews with seven campaign Web masters. They echoed the effectiveness ratings awarded by the campaign managers and directors, saying the Internet helped them conduct research and deal with the press. All seven respondents maintained lists of news media contacts; the media lists of statewide campaigns ranged between 150 and 500, while the House campaigns said their lists ranged between 30 and 45. The Webmasters were more sanguine than their organizational superiors about the Internet’s utility in raising money and assembling and deploying volunteers. Although the Webmaster for Republican Congressman Mike Rodgers in Alabama said that online fundraising wasn’t worth the effort, others appreciated the immediacy and systemization of the activity. The Webmasters found success alerting supporters of upcoming candidate visits in their area and, to a lesser extent, directing people to voter registration sites. Five kept lists of contributors, the same number that kept lists according to issue interest. Four maintained geographic lists, and three, demographic lists. Targeted e-mail communication is clearly an accepted practice among Web masters.

Four campaign Web masters said they sent multiple emails in one day, primarily related to breaking news events and mobilization efforts. The Webmasters agreed that big news events, new television ads, and the last days before an election led to spikes in traffic. The volume of incoming emails varied greatly, from 100 per day for Democrat Frank Lautenberg, who won a Senate seat in New Jersey, to 800 per day for Republican Rick Perry, who retained his office as Governor of Texas. Most Webmasters routed the incoming emails to the appropriate campaign departments, which decided on whether and how to respond. This aspect of online campaigning presents an organizational challenge to political managers: designing a system of email communication which involves every department without resulting in overload, turf wars, security and privacy breaches and such problematic public issuances as leaks, inconsistencies, and misinformation. The content management challenge, like the parallel challenge of list management, is not insuperable. But it needs to be addressed from the top early in a campaign, and that recognition seems a cycle or two away for the bulk of American electoral campaigners.

Best Practices and Other Practices: What Campaigners Did on their Web Sites

Since 1999, the Institute has promoted a set of best practices for online campaigning. These best practices were developed in consultation with political professionals, scholars, and Internet experts, as part of the original mission of the Institute’s precursor organization, the Democracy Online Project. We have argued that, because the Internet is user-driven to a great degree, and because it is also a very public medium, campaigns should adhere to high standards of political discourse in order to win votes and support online.11 Emphasizing transparency and interactivity is not only the right strategy from the standpoint of free democratic politics, but the smart strategy, as our seven Best Practices make clear:

- Making campaign Web sites accessible to everyone opens up volunteering and donating possibilities, not only to Americans with disabilities, but also to those who rely on phone modems.

- Documenting candidate positions and track records not only sets the record straight, it builds trust among online seekers of reliable information, and establishes a line of credibility credit for use if and when scandals, rumors, and other charges surface.

- Exhibiting and extending community ties (candidate memberships, endorsements, and testimonials from unaffiliated citizens) not only encourage the online citizenry to conclude that the candidate is indeed a man or woman of the people, but also embeds the Web site in a denser set of communication links, easing the capacity of the campaign to get its word out quickly and believably, and to attract more visitors to the site.

- Developing, posting, and living by a privacy policy not only protect online visitors against indecent use of personal data, but also protect the campaign against retaliation.

- Explaining rules of financial disclosure and showing that the campaign complies not only assures the public, but also puts patterns of contribution and expenditure in a favorable light.

- Stating the case for the campaign through contrasts (instead of one-sided attacks and boasts) not only elevates the discourse, but also attracts more Net users accustomed to comparison shopping and research.

- Providing interactive and interpersonal opportunities not only boosts political participation, but solidifies campaign support. People will open emails from those who have opened email from them.

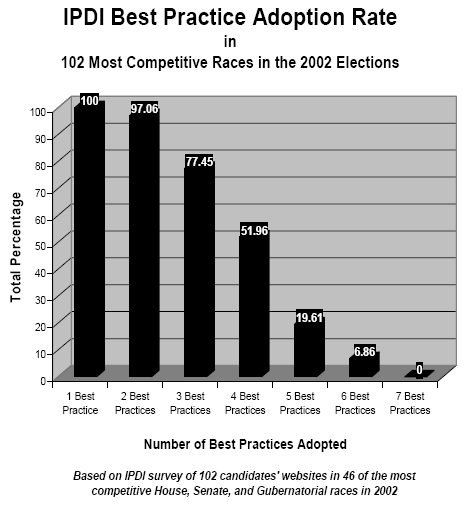

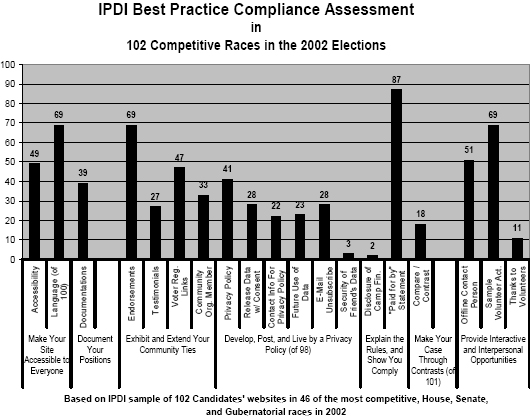

We translated these principles into Internet features that campaigns either did or did not adopt, and then checked the best practice compliance pattern of 102 candidates in 46 of the most competitive races in general elections for the House, Senate, and Governor. (This is the same pool from which the 35 respondents to the questionnaire came.) As Table 2 shows, all the candidates adhered to a feature of at least one best practice, 97% met at least two of them, and 77% conformed to three. Table 3 describes the compliance rates feature by Web site feature.

The disclosure best practice (“Explain the Rules, and Show You Comply”) subsumed the online campaigning features with the greatest and least compliance. On the one hand, 87% included a disclaimer identifying the campaign on their emails. This is an encouraging sign that email will not be construed as a category of campaign communication exempt from disclaimer provisions. On the other hand, only 2% posted online the financial disclosure data that they are required to file by law with the Federal Election Commission, or a link to such data elsewhere on the Web. This attests to the reluctance of campaigns to publicize their contributors, for fear of other campaigns “poaching” the list (an activity punishable by law at the federal level and in many states) and of embarrassing their contributors with publicity. The 2% figure helps create the informational vacuum ably filled by such Web sites as opensecrets.org, which is the most popular Web site by far among political reporters covering campaigns.12 Perhaps if more campaigns presented financial disclosure information on their own sites, in their own terms, they might be able to build more public confidence about the role of money in politics.

Implementing a privacy policy is a complicated operation. IPDI decided to include seven compliance features under the privacy rubric in order to assess the range of privacy policies in force at 2002 campaigns. The poor-to-medium compliance rate is a sign that campaigns are not yet convinced of the importance of assuring Web site visitors that any data they provide will be closely and carefully guarded. This is disturbing, from a civic vantage point; it is also counter-productive, from a strategic vantage point. Research conducted by the Institute in collaboration with the GWU Survey Research Center and the MSN Network reveals a sizable and serious segment of the online citizenry hesitates before giving money or personal information to campaigns for just this reason.13

When the close-race campaigns whose Web sites we examined made reference to the world around them, exhibiting their network of support through links and related content, they emphasized established names and organizations over everyday citizens. Whereas 69% of the sites sported endorsements, only 27% included citizen testimonials. Volunteers were not ignored: 69% of the sites supplied an example of the type of activity online volunteers could perform, and 51% provided contact information so that a Web visitor could interact, online or offline, with someone on the campaign. However, only 11% of the closely contested campaigns thought enough of online volunteers to thank one or more of them publicly on the site. This dearth of public appreciation by campaigns for their volunteers helps explain a finding from the nationwide survey: while 29% of the online citizenry reported receiving an email supporting or opposing a candidate for office, only 17% said they sent such an email. It takes very little technically to forward an email to friends. But the forwarder must be motivated to do so. Campaigns should pay closer attention to cultivating a sense of inclusion among their email recipients.

A mere 18% of the sites examined provided compare and contrast information for citizens interested in rationalizing their voting choice. However, 39% provided some documentation for claims they made about the issues. We consider the ramifications of this mediocre compliance rate on these discourse-related best practices in the next section of the report, where we show that citizens are looking for such information.