Over the past several months, the coronavirus outbreak has become a global pandemic that has disrupted the lives of billions of people and left governments, businesses and even “fact tanks” like Pew Research Center struggling to adapt to a new reality.

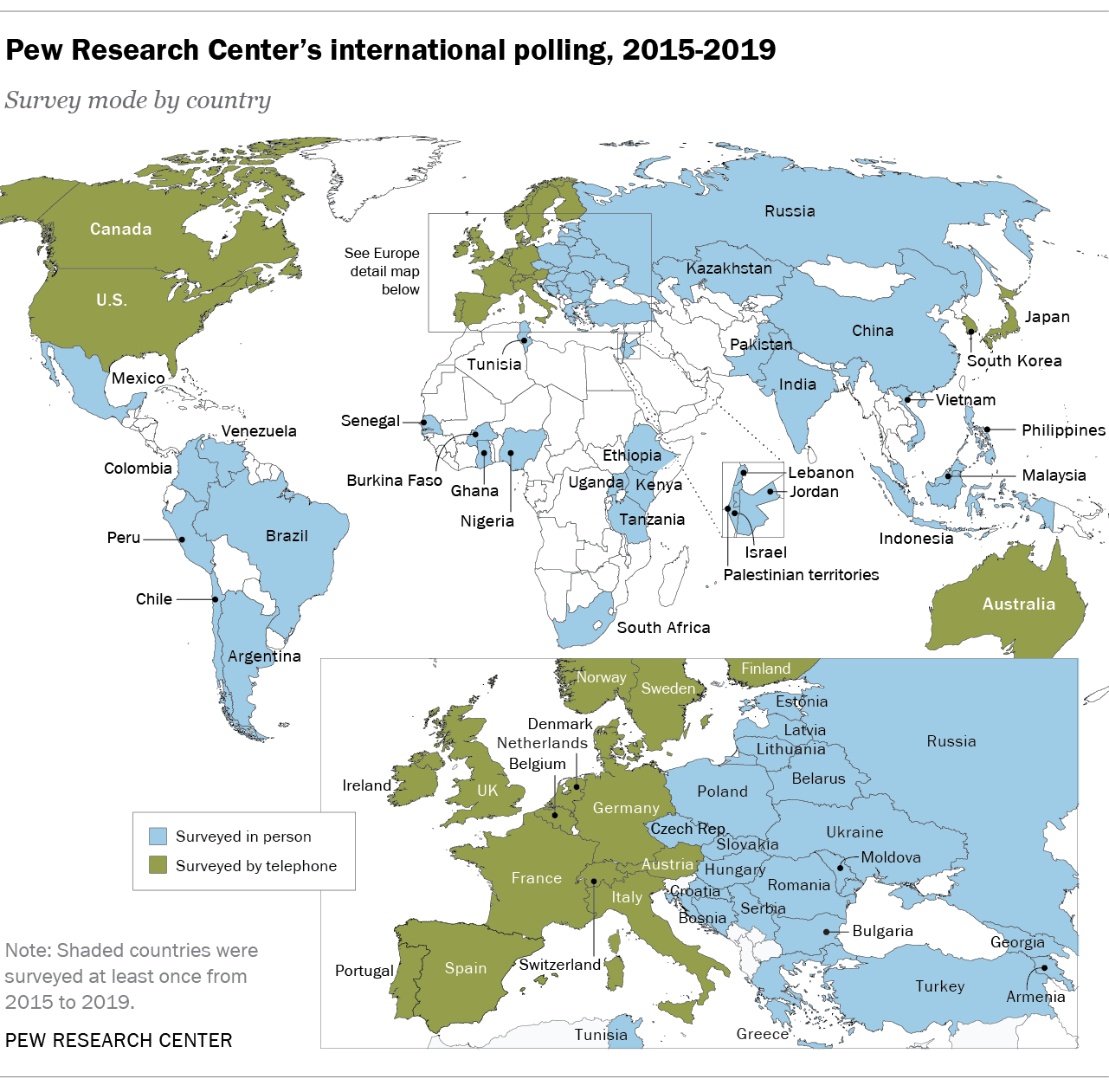

The Center’s response to the COVID-19 crisis has included the difficult decision to suspend much of our international survey work until further notice. The reason? A majority of our surveys around the globe are still conducted face-to-face. We could not in good conscience proceed with data collection that placed interviewers, and the persons with whom they interacted, at risk of contracting the novel coronavirus. (Our polling in countries where surveys are conducted by phone is continuing, as is our U.S. polling, which is conducted primarily online.)

Related video: The coronavirus pandemic’s impact on our polling

In this age of widespread mobile phone ownership, internet access and globe-spanning communications, it may surprise some readers to learn that the Center still relies so heavily on face-to-face interviewing. The objective of our surveys is to represent an accurate cross-section of a country’s population. So, if a sizable share of people in a country do not have access to a phone, a phone survey may not be the best choice. In many countries where this is the case or access to new technologies isn’t widely available, a face-to-face approach can be a better method to collect representative data.

The world of face-to-face surveys

We rely on face-to-face interviewing exclusively in many parts of the world such as Africa, Latin America, and the Middle East and North Africa. We also depend on it in many countries throughout Asia and even parts of Europe. Over the past five years, about two-thirds of Pew Research Center’s international polling has used a face-to-face approach.

Face-to-face interviewing typically requires fieldworkers to travel between communities, walk local streets and knock on the doors of randomly selected households. If someone answers, several minutes are spent randomly selecting an adult age 18 or older to answer the survey. Then the survey interview begins in earnest – sometimes with the interviewer at the doorstep, sometimes inside the house.

In either instance, a respondent and interviewer can be within a few feet of one another for half an hour or more. Once an interview is completed, the interviewer moves on to the next randomly selected house and repeats the process. Not every interview attempt is successful, of course. In the course of a day an interviewer can walk many streets, knock on many doors and interact with many people before fully canvassing their assigned area.

The Center decided it was best to eliminate the possibility that interviewers moving between communities and households might unknowingly spread or contract the coronavirus. We suspended all face-to-face surveys in early March, including in countries with few or no reported cases of the virus. Effectively, we shut down our international face-to-face survey operations until further notice.

Looking ahead

On the same day that we suspended all face-to-face survey fieldwork, we began to explore alternate means of collecting public opinion data around the globe. One alternative was shifting to telephone surveys. Each year, the Center’s Global Attitudes survey conducts telephone surveys with representative samples in roughly a dozen countries, including the United States, Germany, France, the United Kingdom, Japan, South Korea and Australia. We are now actively exploring the possibility of shifting from face-to-face to phone surveys.

While interviewing over the phone alleviates concerns about social distancing and transmission to respondents and their communities, COVID-19 could still be an impediment to fieldwork. If the virus and government lockdowns remain widespread, call centers may be forced to lock their doors. Some centers can equip their staff to work from home, but few firms have a robust, tested system for at-home interviewing. The Center is currently working with local vendors to assess the safety and feasibility of phone interviewing operations in a range of countries.

In the absence of strategies to field representative telephone surveys that are efficient and effective, face-to-face surveys are likely to return as the Center’s principal mode of survey fieldwork around the globe, once the pandemic has subsided. But precisely when face-to-face operations can return to normal is unclear.

Local restrictions on the movement of interviewers may persist after national governments end their states of emergencies. And in the coming months it may prove more difficult to find people willing to open their door to a stranger, even one wearing a mask over their nose and mouth. Lastly, some local polling firms may not survive the economic downturn triggered by COVID-19 virus. The only certainty is that the international polling environment will be different after the pandemic, and the Center will need to adapt.