At Pew Research Center, we study people’s economic lives — from who counts as unemployed to what it means to be middle class. But economic concepts aren’t always as understandable to the rest of us as they are to economists, and the jargon can be difficult to parse.

Here’s a look at some of the most common terms and concepts that come up in our work on the economy, and what they mean.

What’s the difference between income and wealth?

Income and wealth are both key indicators of financial security for a family or an individual. Income is the sum of earnings from a job or a self-owned business, interest on savings and investments, payments from social programs and many other sources. It is usually calculated on an annual or monthly basis.

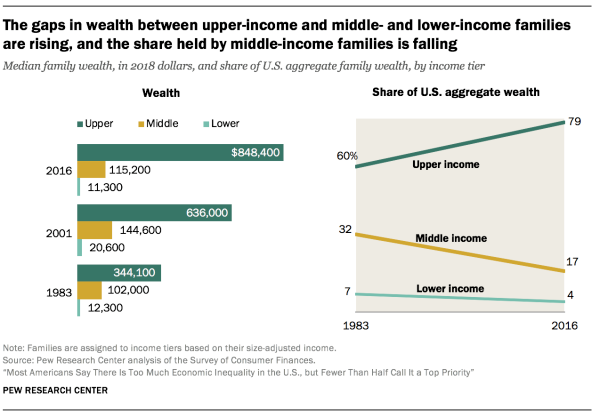

Wealth, or net worth, is the value of assets owned by a family or an individual (such as a home or a savings account) minus outstanding debt (such as a mortgage or student loan). It refers to an amount that has been accumulated over a lifetime or more (since it may be passed across generations). This accumulated wealth is a source of retirement income, protects against short-term economic shocks and provides security for future generations. As of 2016, upper-income families in the U.S. had 7.4 times as much wealth at the median as middle-income families and 75 times as much wealth as lower-income families. These ratios were up from 3.4 and 28 in 1983, respectively, as the below chart shows:

What’s economic inequality and how is it measured?

Economic inequality is a broad term that can relate to income and/or wealth inequality, among other measures of standard of living.

Income inequality measures the distribution of income throughout a population. In the United States, for example, a greater share of aggregate income is now going to upper-income households and the share going to middle- and lower-income households is falling, meaning income inequality has increased.

Similarly, wealth inequality measures the distribution of net worth among the population. In America, the wealth gap between upper- and lower-income households is sharper than the income divide and has grown more rapidly in recent decades.

Income inequality can also be measured using the 90/10 ratio — the ratio of the income needed to place among the top 10% of earners in the U.S. (the 90th percentile) to the income at the threshold of the bottom 10% of earners (the 10th percentile).

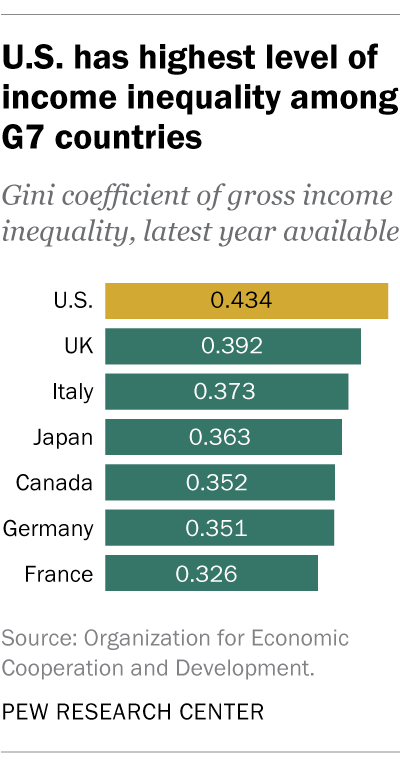

Another common metric is the Gini coefficient, a single number aimed at measuring the degree of inequality in a distribution. It is typically used to measure how far a country’s income distribution deviates from a totally equal distribution. A Gini coefficient of 0 represents perfect equality (all people have the same income), while 1 represents complete inequality (only one person has all of the nation’s income). The U.S. had a Gini coefficient of 0.434 in 2017 (based on gross income, before taxes), representing the highest level of inequality among the G7 countries.

What’s the gender pay gap and how is it measured?

The gender pay gap measures the difference in earnings between men and women. Historically, men in the U.S. have earned more than women on average, but the gap has slowly narrowed over time — especially for younger workers.

Experts don’t entirely understand why the gap exists. While some factors that contribute to the gender wage gap may be quantified — differences in job skills, education level, work experience, union membership, hours worked, industry and occupation — others are more difficult to measure. These include the responsibilities of motherhood and family and their effects on women’s engagement with the workplace when compared with men; gender stereotypes and discrimination; and differences in professional networking and in the inclination to negotiate for raises and promotions.

The Center calculates the gender pay gap based on the median hourly earnings of full- and part-time workers. Read more about why we calculate the pay gap this way.

How is poverty measured?

The poverty line, also referred to as the poverty threshold, is identified by the federal government and used to determine eligibility each year for federal programs, such as SNAP (formerly called “food stamps”) and Medicaid. The poverty line is determined based on what it costs to buy grocery essentials on a thrifty food plan and then multiplying that amount by three. These measures are calculated based on family size and composition, and they are adjusted each year to account for inflation using the Consumer Price Index. In 2020, for example, the U.S. poverty line stood at $26,246 for a family of four. Read more about when and how the poverty line was developed.

At the Center, we often use this measure in our work on topics such as the experience of Americans living in poverty.

How is middle class or middle income defined?

Our research looks at the middle class both in the U.S. and in a global context.

For the U.S., we determine who falls into the middle class by using relative household incomes. For instance, middle-income Americans are adults whose annual household income is two-thirds to double the national median, after incomes have been adjusted for household size. Our analyses of the middle class in U.S. metropolitan areas and states also take into account different costs of living across the country.

In the global context, people who are middle income live on $10.01-$20 a day, which translates to an annual income of about $14,600 to $29,200 for a family of four (expressed in 2011 prices). This is modest by the standards of advanced economies. In fact, it straddles the official poverty line in the United States. Our analyses of the global middle class make sure to adjust for purchasing power parity, in which currency exchange rates are adjusted for differences in the prices of goods and services across countries.

Studying the middle class tells us about trends around economic inequality and adds context to other trends we study, including the labor market and personal and household finances.

Read more about our methodology for the U.S. middle class and how we calculate U.S. income tiers, our 2015 global middle class methodology and our 2021 global middle class methodology. Use our U.S. middle class income calculator or our global middle class calculator to see if your household falls into this group.

Why is income data often adjusted for the number of people in a household?

We adjust household income data because a four-person household with an income of $50,000 faces a tighter budget constraint than a two-person household with the same income.

At its simplest, adjusting for household size could mean converting household income into per capita income. So, a two-person household with an income of $50,000 would have a per capita income of $25,000, double the per capita income of a four-person household with the same total income.

We use a slightly more refined adjustment, in which household income is divided by the square root of the number of people in the household. For purposes of reporting, we then scale the resulting income to reflect a household size of three, the whole number nearest to the average size of a U.S. household, which was 2.5 in 2020.

Read more about our methodology for this adjustment.

Why are there so many different metrics for assessing the state of the labor market?

The short answer is that each one tells us something different about the labor market. The Bureau of Labor Statistics produces a host of metrics, including six measures of what it refers to as “labor underutilization,” along with many other measurements including labor force participation rates, employment-population ratios, average weekly wages, average hours worked and more. The Center uses three main metrics in our work on the topic.

· Unemployment rate: Simply being out of work isn’t enough for the government to count a person as unemployed; he or she also has to be available to work and actively looking for work (or on temporary layoff). The unemployment rate is the share of the labor force — made up of those ages 16 and older with a job, on temporary layoff or actively looking for work — that’s unemployed. In any given month, the unemployment rate can rise or fall based not just on how many people find or lose jobs, but on how many join or leave the active labor force.

· Employment-population ratio: This ratio captures the percentage of a given group’s total civilian non-institutional population, age 16 and older, who are employed. For example, we’ve used this metric to compare employment among different age groups in the U.S.

· Labor force participation rate: This is the share of the 16-and-over civilian non-institutional population either working, on temporary layoff or actively looking for work. This can be affected by more people becoming discouraged from seeking work, leaving temporarily for personal or family reasons, retiring, or deciding to go back to school.

What does it mean to seasonally adjust jobs figures? Would you ever use data that is not seasonally adjusted?

Seasonal adjustment is a statistical technique that accounts for and removes seasonal fluctuations in the size of the labor force and levels of employment and unemployment due to predictable monthly patterns, including weather, crop harvests, holidays and school schedules.

Because these events follow a pretty regular pattern, seasonal adjustment allows for a more accurate measure of how employment and unemployment change from month to month. In general, we use figures that are not seasonally adjusted when comparing the same month across years. Recently, this has been useful in understanding the COVID-19 labor market’s slow recovery. We also use data that is not seasonally adjusted for posts in which we measure summer employment.

Seasonal adjustments are not needed for annual average estimates.

What does it mean to adjust for inflation, and why do you do it?

Inflation is a general increase in the price of goods and services across the economy. As a result of inflation, consumers can purchase fewer goods and services for the same amount of money.

Adjusting for inflation allows us to compare the value of currency over time in order to understand trends such as how the U.S. minimum wage has lost purchasing power over time and to compare the value of workers’ wages across several decades.

This is a statistical method that allows us to compare the difference in purchasing power over time. This tells us more than simply comparing the difference in the number of dollars, which have less value as inflation occurs.

What’s the difference between a government deficit and a government debt?

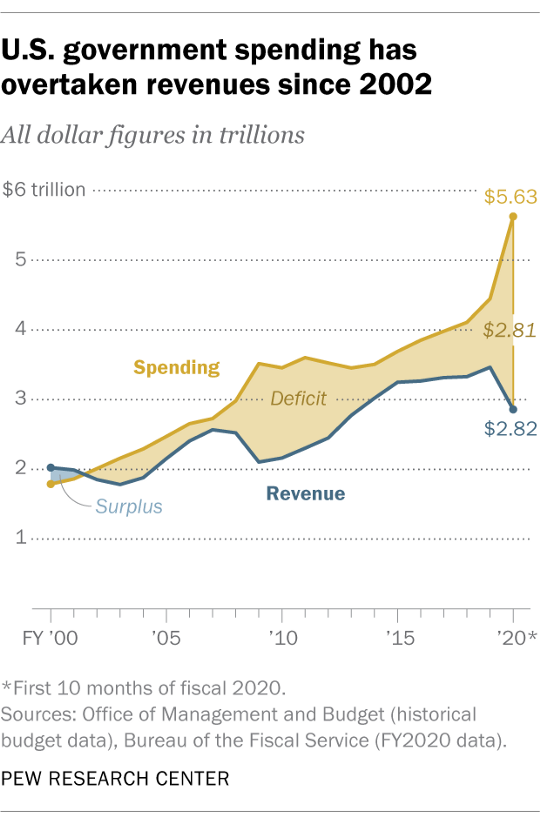

The budget deficit and the national debt are two related, but very different, concepts. The budget deficit is an annual calculation that refers to the difference between what the government spends in a given year and how much it takes in, usually in the form of taxes.

The U.S. national debt is the total amount outstanding the government has borrowed over time for things like covering previous years’ federal deficits. The U.S. national debt stands at $28.5 trillion as of the end of June, and the debt is projected to grow in coming years.