For a small country, Israel holds a place of great importance for three of the world’s major religious groups. The modern Jewish state is not only the “Promised Land” for Jews, but the only country in the world where they form a majority of the population. For Christians, Israel is the “Holy Land,” because it is the place where Jesus’ life and death unfolded. And, for Muslims, Jerusalem is the place where the Prophet Muhammad ascended to heaven.

Although Israel’s religious significance dates to ancient times, the country still receives frequent international attention due in large part to near-constant religious, ethnic and political conflicts. As part of its effort to better understand religion around the world, Pew Research Center has conducted a comprehensive study of religion in Israel, where there are major divisions not only between Jews and Arabs, but also among the major subgroups of Israeli Jews.

Here are several of the key findings from that report, which is based on an extensive survey of more than 5,000 Israelis, conducted in late 2014 and early 2015:

Israeli Jews are largely united on the need for their nation to be a homeland for Jews, regardless of their origins. Across the spectrum of religious observance, Israeli Jews almost unanimously (a combined 98%) support the right of Jews around the world to move to Israel and receive immediate citizenship (also known as making aliyah). A big majority (91%) also say a Jewish state is necessary for the long-term survival of the Jewish people – perhaps in large part because about three-quarters of Israeli Jews (76%) see anti-Semitism as common and increasing around the world. A large majority of Israeli Jews also agree that Israel should give preferential treatment to Jews (79%).

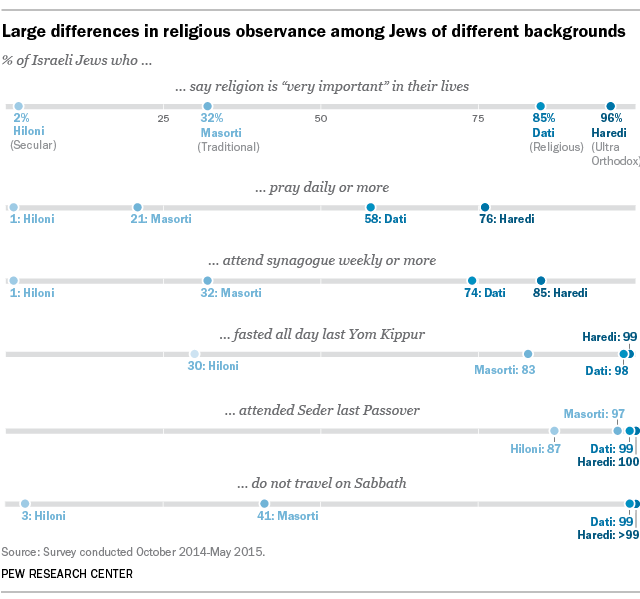

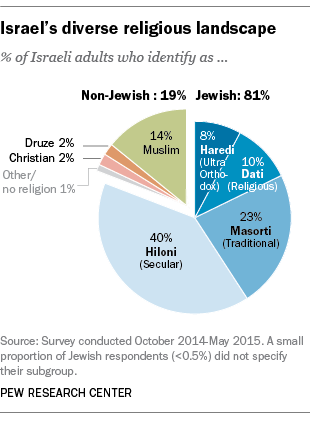

Israeli Jews are far from a homogeneous group. Virtually all Jews in Israel identify with one of four major religious subgroups: Hiloni (“secular”), Masorti (“traditional”), Dati (“religious”) and Haredi (“ultra-Orthodox”). Hilonim are the least religious and make up roughly half of Israeli Jews (49%). Overall, Datiim (sometimes called Modern Orthodox Jews) generally follow Jewish traditions, but they are more integrated into modern society than Haredim and tend to lean to the right politically, especially on issues pertaining to the conflict with the Palestinians. Masortim occupy the religious middle ground, but they appear to be declining as a share of Israeli Jews, while Haredim make up an increasing share (currently 9%).

Jewish groups consistently disagree on a range of specific public policy issues, with more religiously observant Jews saying, for example, that Israel should shut down public transport on the Sabbath (as it mostly does); secular Jews almost universally say public transport should remain running. Jews of varying levels of religious observance also take starkly different positions on some key aspects of the Jewish state. For instance, in a hypothetical conflict between democratic principles and Jewish law (halakha), ultra-Orthodox Jews overwhelmingly say Jewish law should take precedence (89%), while an equally large share of secular Jews say democratic ideals should take priority.

About eight-in-ten (81%) Israeli adults are Jewish, while the remainder are mostly ethnically Arab and religiously Muslim (14%), Christian (2%) or Druze (2%). Overall, the Arab religious minorities in Israel are more religiously observant than Jews. And these groups all are largely isolated from one another socially; there is virtually no religious intermarriage in Israel, and strong majorities of Jews, Muslims, Christians and Druze say all or most of their close friends belong to their own religious group.

Perhaps the strongest indication of the major fractures in Israeli society is that roughly half of Israeli Jews (48%) say Arabs should be transferred or expelled from Israel while a similar share (46%) disagree with this. In addition, Israeli Jews and Arabs disagree on whether the country can be a Jewish state and a democracy at the same time. About three-quarters (76%) of Israeli Jews believe this to be possible, but relatively few Israeli Arabs (27%) agree. And a shrinking share of Israeli Arabs believe Israel and an independent Palestinian state could coexist peacefully (74% believed this in 2013, compared with 50% in the new survey). Few Jews (10%) say Palestinian leadership is sincerely seeking a peace settlement, while few Israeli Arabs (20%) think the Israeli government is genuinely pursuing peace.

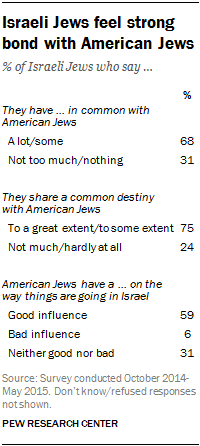

Together, Israel and the U.S. are home to about 80% of Jews globally, and there are strong bonds between the world’s two largest Jewish populations. Most Israeli Jews feel they share a common destiny with U.S. Jews and think U.S. Jews have a good influence on Israeli affairs. American Jews also harbor warm feelings about Israel. Our 2013 survey of U.S. Jews found that most say they are either “very” (30%) or “somewhat” (39%) emotionally attached to Israel, and that caring about Israel is either essential or important to what being Jewish means to them. More than a third of Israeli Jews have traveled to the U.S., and a similar share of U.S. Jews have been to Israel.

Israeli Jews overall are more religious than U.S. Jews, partly because Orthodox Jews make up a greater share of their population. But Israeli Jews also are more religiously polarized than U.S. Jews: They are more likely than U.S. Jews to say they go to synagogue either weekly or never, while Jewish Americans are far more likely to attend synagogue on an occasional basis (e.g., a few times a year, such as for the Jewish High Holidays). Jews in the two countries also have different political ideologies: About half of U.S. Jews (49%) identify as politically liberal in an American context, while only 8% of Israeli Jews place themselves on the left of the Israeli political spectrum. These two political spectrums (liberal/moderate/conservative in the U.S. and left/center/right in Israel) represent different constellations of views on political, economic and social issues in each country. Nevertheless, in both Israel and the U.S., religious Jews tend to lean more to the right, while more secular Jews are centrist or liberal.