After the fall of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s, Israel’s largest wave of Jewish immigrants arrived from Russia and other former Soviet republics. These immigrants, who have far outnumbered those from other countries since Israel achieved statehood, were able to come because of Israel’s Law of Return, which allows all Jews around the world to immigrate and receive immediate citizenship. Israeli Jews support this right virtually unanimously.

There have been several points in Israel’s modern history when waves of immigrants arrived from particular countries or regions. For example, the first wave – largely from Russia and Romania – arrived in the late 19th century, while another took place in the period leading up to World War II (1929-1939) and was mostly made up of German Jews escaping the Nazis. After the founding of the State of Israel in 1948, rising tensions in the region spurred increased immigration by Sephardi Jews from the Middle East and North Africa. And in the 1980s and early 1990s, Israel airlifted thousands of Jews out of war-torn Ethiopia.

About three-quarters of Jewish respondents from the former Soviet Union (FSU) arrived in Israel between 1990 and 1999, in the years following the disintegration of the USSR in 1991. An additional 15% of FSU Jews say they came from 2000 to 2014, while a similar share (12%) say they arrived prior to 1990, according to data from a new Pew Research Center survey of Israel.

The Soviet Jews brought a secular mindset to Israel, and more than two decades later, Jews who were born in the former Soviet Union continue to be noticeably less religious than Israeli Jews overall. FSU immigrants – who make up 14% of all Israeli Jews – also stand out in other ways, including in their demographic characteristics and opinions on the role of religion in Israeli public life.

For instance, most (73%) say they continue to primarily speak Russian at home, while nearly all other Israeli Jews speak Hebrew. In addition, Jews born in the FSU are more likely than Israeli Jews overall to have a college degree (58% vs. 33%). And one-tenth of FSU Jews who are married or living with a partner say their spouse/partner is Christian (4%) or religiously unaffiliated (6%) – in contrast with Israeli Jews overall, among whom only about 2% say they have a spouse or partner who is not Jewish.

Religiously, the vast majority of FSU-born Jews in Israel (81%) self-identify as secular (Hiloni), compared with 49% of all Israeli Jews. This fact is evident when it comes to their views about religion and politics: FSU Jews are adamantly against religious involvement in government. About eight-in-ten say, generally, that religion should be kept separate from government policies (79%), and similar shares oppose, specifically, making halakha (Jewish law) the state law for Jews in Israel (81%) and shutting down public transportation on the Sabbath (81%). Fewer Israeli Jews overall take these positions.

Although a majority of FSU-born Israeli Jews (61%) say Israel can be both a democracy and a Jewish state at the same time, they are more likely than Israeli Jews overall to say this is not possible (33% vs. 20%). And in the event of a hypothetical conflict between halakha and democratic principles, Israeli Jews who were born in former Soviet republics overwhelmingly say democracy should take precedence (72%, compared with 62% of all Israeli Jews).

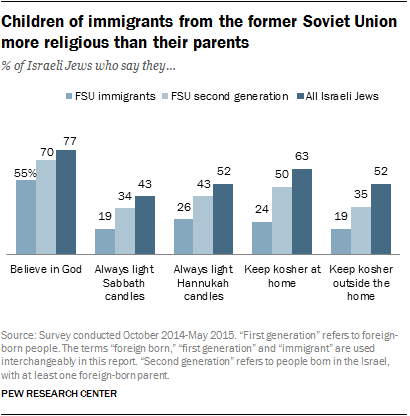

Not surprisingly, when it comes to their own religious beliefs and practices, FSU Jews also are considerably more secular than Israeli Jews overall based on a number of measures, such as belief in God, lighting Sabbath candles and keeping kosher. But the survey also finds that the children of FSU Jews (i.e., second-generation immigrants) are significantly more religiously observant than their parents’ generation, and their beliefs and practices are closer in line with those of the Israeli Jewish public overall.

For example, children of FSU immigrants are more likely than their parents to believe in God (70% vs. 55%). Only 60% of second-generation FSU Jews say they are Hiloni (secular), compared with 81% of FSU immigrants who say so. And while 4% of first-generation immigrants say they are Haredi (ultra-Orthodox), among the second generation, this proportion has climbed to 14%.