After the June 2013 leaks by government contractor Edward Snowden about National Security Agency surveillance of Americans’ online and phone communications, Pew Research Center began an in-depth exploration of people’s views and behaviors related to privacy. Our report earlier this year about how Americans think about privacy and sharing personal information was a capstone of this two-and-a-half-year effort that examined how people viewed not only government surveillance but also commercial transactions involving the capture of personal information.

Soon after the Snowden leaks surfaced, Americans were almost equally divided in a 2014 survey over whether the leaks had served or harmed the public interest. And, at that time, a majority of Americans believed Snowden should be prosecuted. (A campaign, led by the American Civil Liberties Union, has since been organized to seek a pardon for him.)

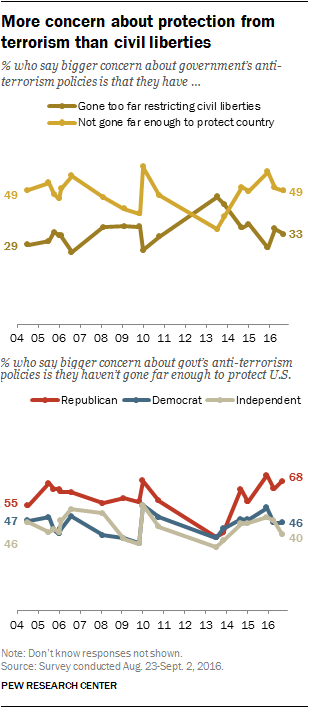

However much the Snowden revelations may have contributed to the debate over privacy versus anti-terrorism efforts, Americans today – after a series of terrorist events at home and abroad – are more concerned that anti-terrorist programs don’t go far enough than they are about restrictions on civil liberties. An August-September survey found that Americans held that view by a 49% to 33% margin.

In this digital age, Americans’ awareness and concerns over issues of privacy also extend beyond the kinds of surveillance programs revealed by Snowden and include how their information is treated by companies with which they do business. Our research also has explored that subject in depth. Here are some of the important findings that emerged from this work:

Overall, Americans are divided when it comes to their level of concern about surveillance programs. In a survey conducted November 2014-January 2015, 52% described themselves as “very concerned” or “somewhat concerned” about government surveillance of Americans’ data and electronic communications, compared with 46% who described themselves as “not very concerned” or “not at all concerned” about the surveillance. Those who followed the news about the Snowden leaks and the ensuing debates were more anxious about privacy policy and their own privacy than those who did not.

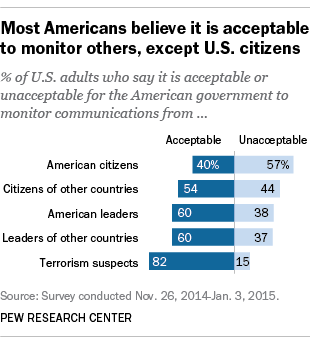

The public generally believes it is acceptable for the government to monitor many others, including foreign citizens, foreign leaders and American leaders. Yet 57% said it was unacceptable for the government to monitor the communications of U.S. citizens. At the same time, majorities supported monitoring of those particular individuals who use words like “explosives” and “automatic weapons” in their search engine queries (65% said that) and those who visit anti-American websites (67% said that).

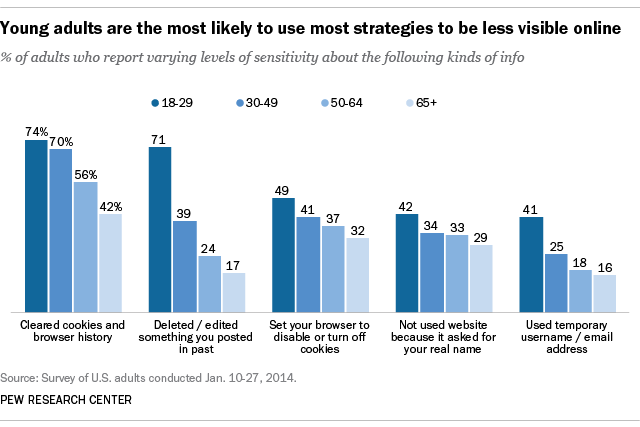

Some 86% of internet users have taken steps online to remove or mask their digital footprints, but many say they would like to do more or are unaware of tools they could use. The actions that users have taken range from clearing cookies to encrypting their email, from avoiding using their name to using virtual networks that mask their internet protocol (IP) address. And 55% of internet users have taken steps to avoid observation by specific people, organizations or the government. Many say the purpose of their attempted anonymity is to avoid “social surveillance” by friends and colleagues, rather than the government or law enforcement.

At the same time, many express a desire to take additional steps to protect their data online. When asked if they feel as though their own efforts to protect the privacy of their personal information online are sufficient, 61% say they feel they “would like to do more,” while 37% say they “already do enough.” Even after news broke about the NSA surveillance programs, few Americans took sophisticated steps to protect their data, and many were unaware of robust actions they could take to hide their online activities. Some 34% of those who said they were aware of the NSA surveillance programs in a July 2013 survey (30% of all adults) had taken at least one step to hide or shield their information from the government. But most of those actions were simple steps, such as changing their privacy settings on social media or avoiding certain apps, rather than tools like email encryption programs, “don’t track” plug-ins for browsers or anonymity software.

Americans express a consistent lack of confidence about the security of everyday communication channels and the organizations that control them – particularly when it comes to the use of online tools. And they exhibited a deep lack of faith in organizations of all kinds, public or private, in protecting the personal information they collect. Only tiny minorities say they are “very confident” that the records maintained by these organizations will remain private and secure.

Some 74% say it is “very important” to them that they be in control of who can get information about them, and 65% say it is “very important” to them to control what information is collected about them. Personal control matters a lot to people. If the traditional American view of privacy is the “right to be left alone,” the 21st-century refinement of that idea is the right to control their identity and information. They understand that modern life won’t allow them to be “left alone” and untracked, but they do want to have a say in how their personal information is used.

Many Americans struggle to understand the nature and scope of data collected about them. When it comes to their own role in managing their personal information, most adults are not sure what information is being collected or how it is being used.

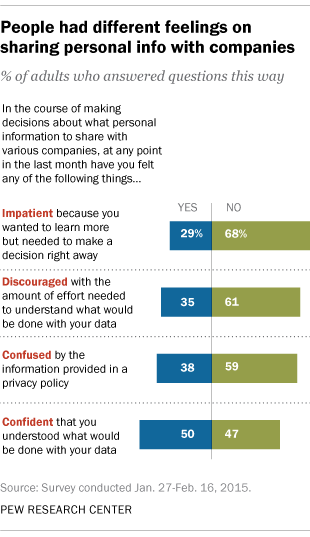

While half of those surveyed said they felt confident they understood how their information would be used, 47% said they were not, and many of these people felt confused, discouraged or impatient when trying to make decisions about sharing their personal information with companies.

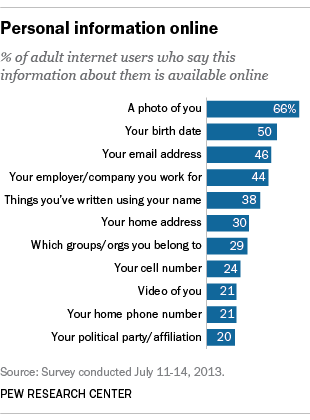

Fully 91% of adults agree or strongly agree that consumers have lost control of how personal information is collected and used by companies. Half of internet users said they worry about the amount of information available about them online, and most said they knew about key pieces of their personal information that could be found on the internet. Only 9% say they feel they have “a lot” of control over how much information is collected about them and how it is used. Indeed, experts we canvassed about the future of privacy argued that privacy was no longer a “condition” of American life. Rather, they asserted that it was becoming a commodity to be purchased.

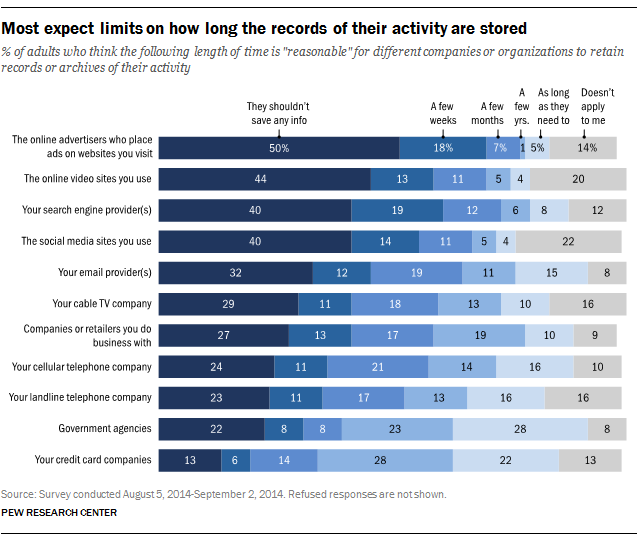

For most Americans who are making decisions about sharing their information in return for a product, service or other benefit, the context and conditions of the transactions matter. When considering this basic digital era trade-off, many are in an “It depends” frame of mind. Risk-benefit calculations that enter people’s minds during the decision process include the terms of the deal; the circumstances of their lives; whether they consider the company or organization involved to be trustworthy; what happens to their data after they are collected, especially if the data are made available to third parties; and how long the data will be retained.

For instance, 54% of Americans consider it an acceptable trade-off to have surveillance cameras in the office in order to improve workplace security and help reduce thefts. But a scenario involving the use of a “smart thermostat” in people’s homes that might save energy costs in return for insight about people’s comings and goings was deemed “acceptable” by only 27% of adults. It was seen as “not acceptable” by 55%.

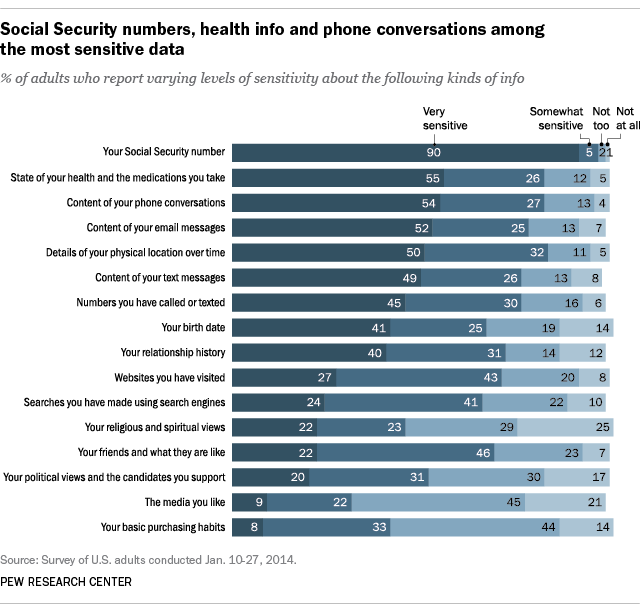

Indeed, most Americans assign different degrees of value to different pieces of information. Social Security numbers are ranked as the most sensitive information, while people’s purchasing habits ranked lowest as something they felt was very sensitive.

Young adults generally are more focused than their elders when it comes to online privacy. Younger adults are more likely to know that personal information about them is available online and to have experienced privacy problems. By the same token, our surveys have found that those ages 18 to 29 are more likely than older adults to say they have paid attention to privacy issues, tried to protect their privacy and reported some kind of harm because of privacy problems. They are more likely to have limited the amount of personal information available about them online, changed privacy settings, deleted unwanted comments on social media, removed their name from photos in which they were tagged, and taken steps to mask their identities while online. It is also true that younger adults are more likely to have shared personal information online.

A majority of the U.S. public believes changes in law could make a difference in protecting privacy – especially when it comes to policies on retention of their data. In the midst of all this uncertainty and angst about privacy, Americans are generally in favor of additional legal protections against abuses of their data. Some 68% of internet users believe current laws are not good enough in protecting people’s privacy online; and 64% believe the government should do more to regulate advertisers. Most expect at least some limits on retention policies by data collections. And a majority (64%) support more regulation of advertisers and the way they handle personal information. When asked about the data the government collects as part of anti-terrorism efforts, 65% of Americans say there are not adequate limits on “what telephone and internet data the government can collect.”

Many technology experts predict that few individuals will have the energy or resources to protect themselves from “dataveillance” in the coming years and that privacy protection will likely become a luxury good. Another prediction from 2,511 experts we canvassed was that the prospect of achieving bygone notions of privacy will become more remote as the Internet of Things takes hold and people’s homes, workplaces and the objects around them will “tattle” on them. A more hopeful theme about privacy’s future was sounded by experts who argued that new technology tools would become available that would give consumers power to negotiate on equal footing with corporations about information sharing and also allow them to work around governments trying to collect data.

Note: This is an update of a post originally published Jan. 20, 2016.