Thanks to scientific advancements, brain chip implants are already being tested in individuals to help them cope with an injury or ailment. But when it comes to the potential use of such implants to give an already healthy and capable person abilities that they do not currently have, Americans are more wary than enthusiastic.

Some 54% of U.S. adults foresee a future where computer chips will routinely be embedded in our bodies. But as with other kinds of potential human enhancements, a recent Pew Research Center survey found that more Americans are worried about the idea of an implanted brain chip (69%) than are enthusiastic (34%). And a minority of U.S. adults – 32% – would want this implanted device for themselves.

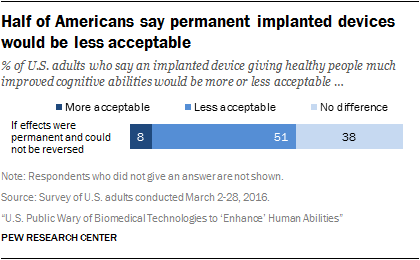

Several factors help explain people’s views about emerging technologies and their potential use to augment human abilities. Opinions about implanting devices often hinge on whether the effects would be permanent and irreversible. Asked specifically about the possibility that the effects of an implanted brain chip would be permanent, about half of U.S. adults (51%) say this would make the idea less acceptable to them.

In focus groups conducted by the Center, many participants categorized brain chip implants as unnecessary for a healthy person. One person described the idea of brain chips for enhancement as “cosmetic surgery for the brain.” Another said: “I feel like it’s low value. I feel like it’s just going to be another thing that increases our vanity. … It just feels shallow to me.”

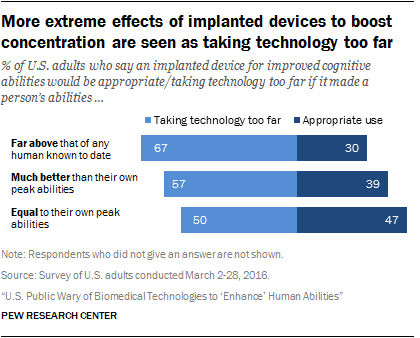

Americans are also less accepting of implanted devices that would result in more dramatic rather than modest changes in the recipient. For example, the public is closely divided over whether an implanted device that improves a person’s mental functioning to a level equal to their current peak abilities would be appropriate or taking technology too far. By a ratio of more than two-to-one, people are much more likely to say that implanting devices that dramatically increase a person’s peak abilities would be taking technology too far.

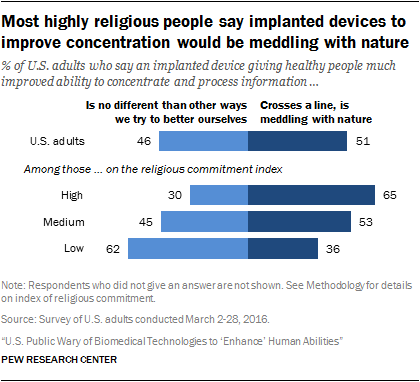

While a 2014 Pew Research Center survey found only a handful of science-related issues where people’s religious beliefs and practices have a strong connection to their views, brain chip implants are one of those topics where Americans who are more religious are more likely to view such procedures with wariness. One factor feeding into these beliefs is that the potential use of a brain chip to make peoples’ minds work better raises fundamental questions about what it means to be human.

About two-thirds (65%) of people who are high in religious commitment (regardless of their particular religious affiliation) say an implanted device for healthy people would be meddling with nature and crossing a line we should not cross. By contrast, people who are low in religious commitment (who seldom pray or attend religious services and say religion is not important in their lives) are much more inclined to consider brain chip implants to be in keeping with other ways that humans have tried to better themselves over time.

Beyond differences in people’s views on brain chips by religion, it is also worth noting that Americans’ opinions about implanted devices are often linked to how much (or how little) people have heard about them. A majority of U.S. adults (61%) say they have heard nothing at all about the idea of an implanted computer chip in the brain. About a third of Americans (32%) say they have heard a little about this, while only 6% say they have heard a lot. Those who have heard at least a little about these implanted devices are more inclined to want this for themselves.

This might suggest that as the idea of implanting brain chips becomes more familiar in the future, people will become more aware of the idea and more comfortable with it. However, this pattern could simply reflect that technology enthusiasts not only seek out information about new technological developments but also tend to favor these possibilities. Those who later hear about the technologies might not be as keen about them.

Still, perceptions can change over time. The history of technology is full of examples where many people thought new gadgetry, like early cars or early smartphones, were an unnecessary luxury. Eventually, these became items that most Americans felt they could not do without. It will take more time – perhaps decades or more – to know whether implanting brain chips will become a commonplace human enhancement or whether this initial wariness will persist in a way that blocks widespread implementation of the practice.