On average, Muslim men around the world have more formal schooling than women, a fact well-known by Nobel Peace Prize-winner Malala Yousafzai and other Muslim activists for female education. But while the Muslim gender gap in education remains large, relative to most other major religious groups, it has narrowed in recent generations: Muslim women have made greater educational gains than Muslim men in most regions of the world, according to Pew Research Center’s comprehensive new study on educational attainment among the world’s major religious groups.

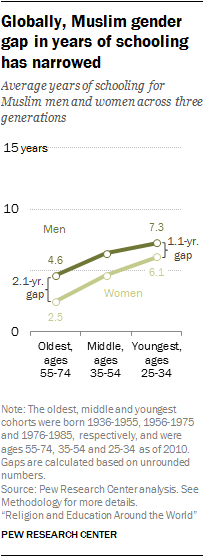

The study looked at changes in educational attainment across three recent generations, finding that the youngest generation of Muslim adults analyzed (born 1976 to 1985) have far more formal education than those in the oldest generation analyzed (born 1936 to 1955). While both men and women are contributing to these gains, women have been gaining at a faster rate.

The oldest Muslim women in the study averaged just 2.5 years of schooling, compared with 4.6 years for men – a gap of 2.1 years. Young women (ages 25 to 34 as of 2010), by comparison, have averaged more than twice as many years of formal education as their female elders (6.1 years), and now trail young men (7.3 years) by just over a year.

Another way to measure education is by looking at the percentage of people with no formal schooling, and the Muslim gender gap also has narrowed from this perspective. Globally, a majority of the oldest generation of Muslim women analyzed (64%) had no formal schooling, but this figure is 31 percentage points lower among the youngest generation (33%). Meanwhile, the share of Muslim men who never received any formal education dropped by a more-modest 20 points across three generations (43% to 23%).

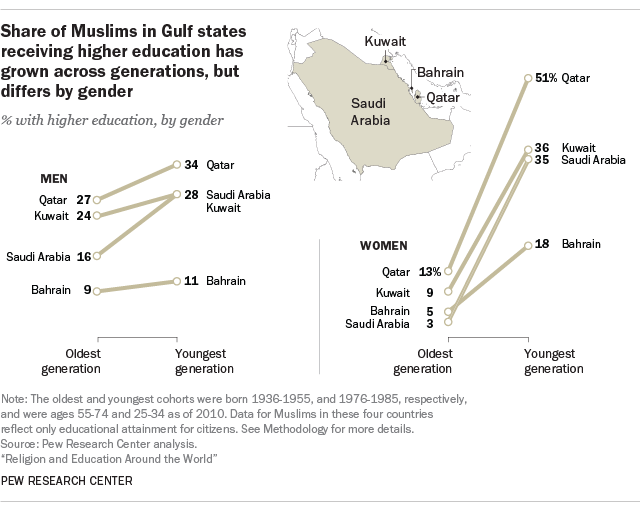

At the other end of the attainment spectrum, relatively few Muslim men and women have post-secondary degrees. But in some places, Muslim women’s gains in post-secondary education were so dramatic that the gender gap has reversed, meaning that, in the youngest generation, more Muslim women than men hold college degrees. This pattern has been particularly striking in Qatar, Kuwait, Bahrain and other nations that are members of the Gulf Cooperation Council, a regional political and economic union.

In Saudi Arabia, for example, the share of Muslim women holding post-secondary degrees rose from 3% in the oldest generation analyzed to 35% in the youngest generation. Among Saudi Muslim men, the share with higher education rose from 16% to 28%.

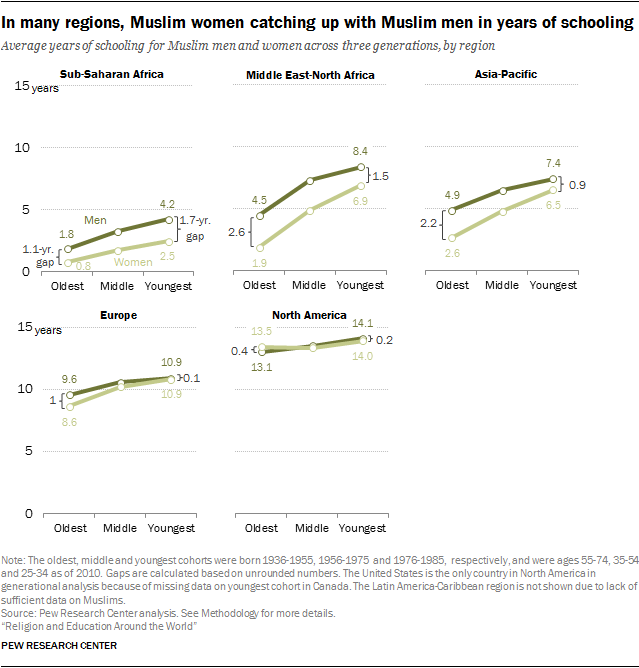

This general pattern of Muslim women making greater educational gains than Muslim men has not extended to sub-Saharan Africa. Across the three generations in our study, Muslim gender gaps in that region remained largely unchanged and sometimes even widened. Although Muslim women in this region have made some gains, they have done so at a slower rate than their male peers.

The gender gap in average years of schooling illustrates this trend. The youngest Muslim men in sub-Saharan Africa gained 2.4 more years of schooling, on average, than the oldest Muslim men, while the youngest Muslim women gained only 1.7 more years of schooling over their elders.

But in other regions, Muslim women have gained on men. In Europe, for instance, Muslim women and men average virtually the same number of years of schooling among the youngest generation analyzed, and in the Asia-Pacific and Middle East-North Africa regions – together home to most of the world’s Muslims – the gaps have narrowed considerably.