Many Americans believe it is common for police officers to fire their guns. About three-in-ten adults estimate that police fire their weapons a few times a year while on duty, and more than eight-in-ten (83%) estimate that the typical officer has fired his or her service weapon at least once in their careers, outside of firearms training or on a gun range, according to a recent Pew Research Center national survey.

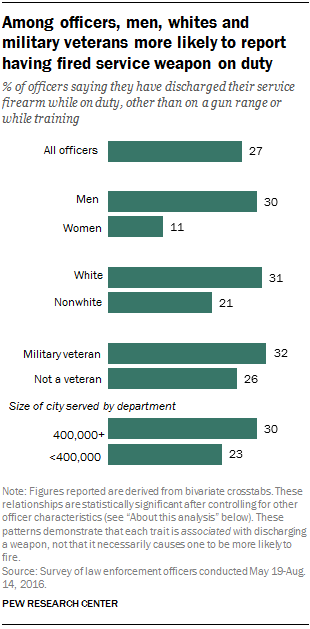

In fact, only about a quarter (27%) of all officers say they have ever fired their service weapon while on the job, according to a separate Pew Research Center survey conducted by the National Police Research Platform. The survey was conducted May 19-Aug. 14, 2016, among a nationally representative sample of 7,917 sworn officers working in 54 police and sheriff’s departments with 100 or more officers.

But among police officers, are some more likely than others to have fired their weapon in the line of duty?

Overall, those who have fired a weapon on duty and those who haven’t are broadly similar in terms of their personal traits, the types of communities they serve and even their attitudes about crime-fighting. But an analysis of the survey results finds some modest but intriguing differences.

To start, male officers, white officers, those working in larger cities and those who are military veterans are more likely than female officers, racial and ethnic minorities, those in smaller communities and non-veterans to have ever fired their service weapon while on duty. Each relationship is significant after controlling for other factors that could be associated with firing a service weapon.

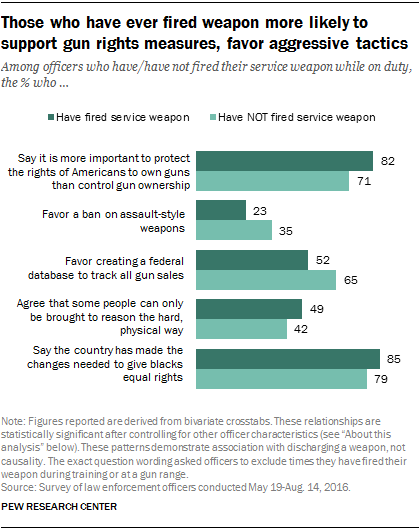

At the same time, an analysis of officers’ views on a range of law enforcement issues finds that having fired a service weapon bears a modest but consistent relationship to several key attitudes. For example, while solid majorities of those who have and have not fired their weapon favor protecting gun rights over controlling gun ownership, officers who have fired their weapon are somewhat more likely to favor protecting gun rights than those who have not used their firearm. In fact, across a number of gun-related questions, officers who have fired their weapon while on duty are less likely to favor some measures that would restrict gun ownership or provide more government oversight over gun sales.

Officers who have fired their weapon differ from their colleagues on other issues as well. For example, they are somewhat more likely to approve of harsh, physical methods for dealing with some people than their colleagues who have not discharged their gun (49% vs 42%). They also are somewhat more likely to say that the country has made the changes needed to assure equal rights for blacks than to believe more changes are needed (85% among those who have fired their service weapon vs. 79% among officers who have not). Again, the relationship between these attitudes and whether or not an officer has fired his or her service weapon is statistically significant even after controlling for other factors in the analysis.

Before examining these and other results in more detail, two important cautions must be raised. First, the fact that an officer has fired their service weapon while on duty should not be interpreted to mean that the officer shot someone. (The question asked: “Other than on a gun range or while training, have you ever discharged your service firearm while on duty, or have you not done this?”) Nor were officers asked how many times they have fired their service weapon in their careers or whether they currently work for the same agency where they fired their service weapons. The study is a snapshot of officers who are employed currently, and it describes their past experiences.

Second, it is important to bear in mind that the factors that are associated with firing a duty weapon cannot necessarily be said to have caused officers to discharge their gun. For example, while the study shows that officers working in larger communities are more likely than those in smaller communities to have fired their weapon sometime in their law enforcement careers, the data don’t allow one to say that working in a large city or county is the reason – or even a reason – why officers are disproportionately likely to have fired their guns. Other factors common to both gun use while on duty and working in a large city may be the real cause. (For more, see “About this analysis” below.)

Male officers, whites more likely to have fired weapon

Not all demographic characteristics are equally good predictors of gun use. Gender is one of the best, this analysis finds. Male officers are more than twice as likely as female officers to have fired their weapon (30% vs. 11%). This relationship remains significant even after accounting for gender differences in job assignment, length of service, race, age, the size of the city and department they work for, and other factors.

White officers also are more likely than officers who are racial or ethnic minorities to have fired their weapon (31% vs. 21%). Veteran status also differentiates those who have discharged their weapons from those who have not. Veterans make up 28% of all police officers, the survey finds, and among this group, about three-in-ten (32%) have fired their gun, compared with 26% of those who have not served in the military.

Differences by city characteristics

The population size of the area where the officer works also is associated with the probability that an officer will have fired his or her weapon while on duty. While 23% of officers in communities with fewer than 400,000 residents have discharged their gun, 30% of officers in areas with populations of 400,000 or more say they have done so. (As a point of reference, Tulsa, Oklahoma and Minneapolis, Minnesota each have about 400,000 residents, though police departments in these cities were not among those in the sample.)

It’s possible, of course, that this relationship is not about the size of the community but about the level of violence that may be present in bigger cities. To test this theory, we combined our survey data with violent crime rates from 2015 – the most recent year available – in each of the 54 areas we studied.

The resulting analysis finds that the violent crime rate in the city or county where an officer works has a mixed impact on the likelihood that an officer has fired his or her service weapon. Officers who currently work in cities with comparatively low crime rates are significantly more likely to have fired their weapon than police in cities that fall in the middle. (Violent crime is defined as murder, rape, armed robbery and aggravated assault; the data used in this analysis were reported by individual police agencies to the FBI.)

About one-in-five officers (22%) in areas with at least six and but fewer than 10 violent crimes per 1,000 residents in 2015 have ever fired their service weapon. By contrast, about a third (32%) of officers who work in areas with a lower violent crime rate have discharged their gun. In areas where the violent crime rate is 10 or more, 28% of officers have fired their weapon. However, that proportion is not significantly different from the share that works in communities with fewer than six or six to fewer than 10 violent crimes per 1,000 residents.

Officers’ attitudes and gun use on the job

Do officers who have ever fired their weapon differ in terms of their attitudes from those who have not? To answer this question, we compared the views of the two groups of officers across a range of questions.

The analysis finds that officers who have fired their weapon are more supportive of gun rights than those who have not. About eight-in-ten officers who have fired their service weapon (82%) say protecting the right of Americans to own a gun is more important than controlling gun ownership. By contrast, about seven-in-ten (71%) of those who have not discharged their firearm while on duty share this view.

Officers who have fired their weapon are also less likely than their colleagues to support restrictive gun measures, even after controlling for other factors that may be related to these attitudes. For example, about a quarter (23%) of officers who have fired their gun support a ban on assault-style weapons, compared with 35% of other officers. About half (52%) of those who have shot their weapon favor creating a federal database to track gun sales, a move supported by roughly two-thirds (65%) of other officers.

Officers who have fired their weapon also are more likely than those who have not to agree that “some people can only be brought to reason the hard, physical way” (49% vs. 42%).

Finally, the analysis finds a modest difference between the two groups of officers in terms of their views of racial progress. The survey finds that 85% of officers who have fired their service weapon while on duty say the country has made the necessary changes to give blacks equal rights with whites, a view shared by 79% of officers who have not fired their weapon.

About this analysis

Findings reported in the graphics and text of this analysis reflect simple two-way relationships. In other words, the findings on gender reflect the percentage of men and women officers who have ever fired their weapon. Each of these findings was further subjected to more rigorous analysis using a statistical technique known as logistic regression. This technique estimates the independent effect of each characteristic, holding the other factors in the analysis constant.

The 14 factors controlled for in the logistic analysis were the officer’s gender, age, race/ethnicity, education, years in law enforcement, current assignment and rank, veteran status, size of the officer’s department, whether the officer’s agency was a police or sheriff’s department, whether the department was located in an urban or suburban area, the census region where the officer’s department was located, the size of the population served by the officer’s department and the city or county’s violent crime rate in 2015. Unless otherwise noted, only those relationships that were statistically significant after controlling for these factors are reported.