Doug Jones has officially taken his freshly won U.S. Senate seat, becoming Alabama’s first Democratic senator in 21 years. Jones and Republican Sen. Richard Shelby now make up what has become something of a rarity in the Senate: a state delegation split between two senators of different parties.

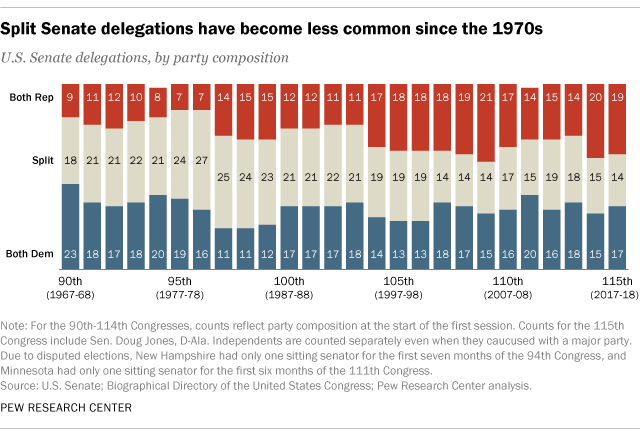

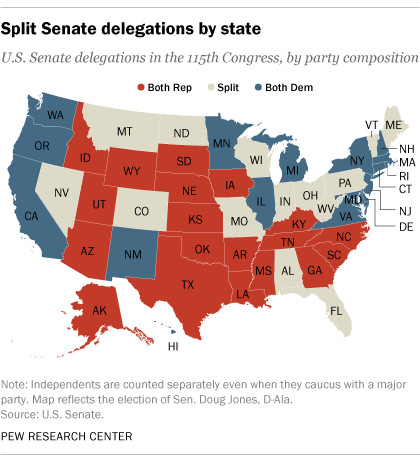

Before Jones’ win in December, only 13 states had split Senate delegations in the current Congress. That was the fewest in the past five decades, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of Senate membership data going back to the 90th Congress (1967-68). Now, with 14 split delegations, the current Senate is tied with several other Congresses for second-fewest in the past 50 years – there were 14 during most of the 107th Congress and all of the 108th and 109th Congresses, spanning 2001 through early 2007.

Split delegations were fairly uncommon in the first four decades after the direct election of senators began in 1913. The low point, according to University of Minnesota political scientist Eric Ostermeier, came during the 84th Congress (1955-56), when just nine states had both a Republican and a Democrat representing them in the Senate.

But politically divided delegations became more common in the 1960s and ’70s as decades-old patterns of state-level party dominance began to break down. By the 96th Congress of 1979-80, more than half the states (27) had split delegations, and from 1969 through 1994 more than 20 states sent split delegations to the Senate. Since then, despite some ups and downs, the trend has been toward more single-party delegations. As of now, 19 states have two Republican senators and 17 have two Democrats.

Over the past 50 years, only Kansas has never had a split delegation. In fact, the last time the Sunflower State elected a Democratic senator was in 1932, during the depths of the Great Depression. Vermont, on the other hand, has consistently had a split delegation since Democrat Patrick Leahy took his seat in 1975; all his partners since have been Republicans or independents (as is Vermont’s other senator, independent Bernie Sanders).

Political scientists have explored the question of why a state’s voters, whose party preferences and turnout behavior presumably don’t change that much from one election cycle to another, would elect senators of different parties. One school of thought has theorized that some voters deliberately seek to balance their state’s delegation, though other researchers have not found support for that idea. Other researchers focus on diverse electorates as predictors of split delegations, argue for candidate-specific factors (such as financing, campaigning skill and the presence or absence of scandal), or tie the ebb and flow of split delegations to broader partisan realignments.

Whatever the explanation, several states have sent pairs of senators to Washington who were so ideologically disparate that their votes all but canceled each other out. Past examples include Minnesota’s Paul Wellstone (D) and Rod Grams (R), North Carolina’s John Edwards (D) and Jesse Helms (R), and California’s Alan Cranston (D) and S.I. Hayakawa (R). Roll Call recently took a look at some of the current Senate’s “odd couples,” awarding the top spot to Wisconsin’s Ron Johnson (R) and Tammy Baldwin (D).

Other times, senators in split delegations cluster closer to the center of the ideological spectrum, as measured by a political science tool called DW-NOMINATE that scores lawmakers based on their voting records. In the current Senate, states that have relatively centrist split delegations include Maine (Republican Susan Collins and independent Angus King), West Virginia (Democrat Joe Manchin and Republican Shelly Moore Capito) and North Dakota (Republican John Hoeven and Democrat Heidi Heitkamp).

Correction: A previous version of this post misstated the current Senate’s ranking in split delegations. With Jones sworn in, it is tied for second-fewest in the years reviewed.