Days of protests across the United States in the wake of George Floyd’s death in the custody of Minneapolis police have brought new attention to questions about police officers’ attitudes toward black Americans, protesters and others. The public’s views of the police, in turn, are also in the spotlight. Here’s a roundup of Pew Research Center survey findings from the past few years about the intersection of race and law enforcement.

How we did this

Most of the findings in this post were drawn from two previous Pew Research Center reports: one on police officers and policing issues published in January 2017, and one on the state of race relations in the United States published in April 2019. We also drew from a September 2016 report on how black and white Americans view police in their communities. (The questions asked for these reports, as well as their responses, can be found in the reports’ accompanying “topline” file or files.)

The 2017 police report was based on two surveys. One was of 7,917 law enforcement officers from 54 police and sheriff’s departments across the U.S., designed and weighted to represent the population of officers who work in agencies that employ at least 100 full-time sworn law enforcement officers with general arrest powers, and conducted between May and August 2016. The other survey, of the general public, was conducted via the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP) in August and September 2016 among 4,538 respondents. (The 2016 report on how blacks and whites view police in their communities also was based on that survey.) More information on methodology is available here.

The 2019 race report was based on a survey conducted in January and February 2019. A total of 6,637 people responded, out of 9,402 who were sampled, for a response rate of 71%. The respondents included 5,599 from the ATP and oversamples of 530 non-Hispanic black and 508 Hispanic respondents sampled from Ipsos’ KnowledgePanel. More information on methodology is available here.

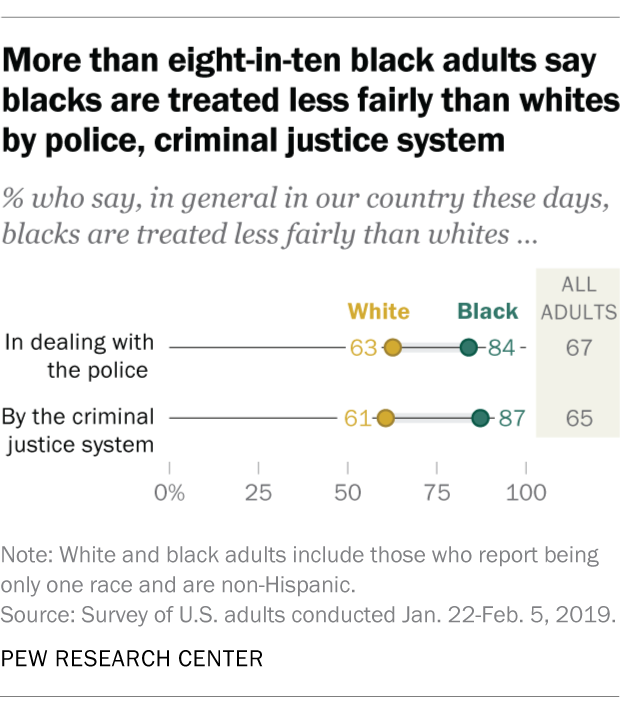

Majorities of both black and white Americans say black people are treated less fairly than whites in dealing with the police and by the criminal justice system as a whole. In a 2019 Center survey, 84% of black adults said that, in dealing with police, blacks are generally treated less fairly than whites; 63% of whites said the same. Similarly, 87% of blacks and 61% of whites said the U.S. criminal justice system treats black people less fairly.

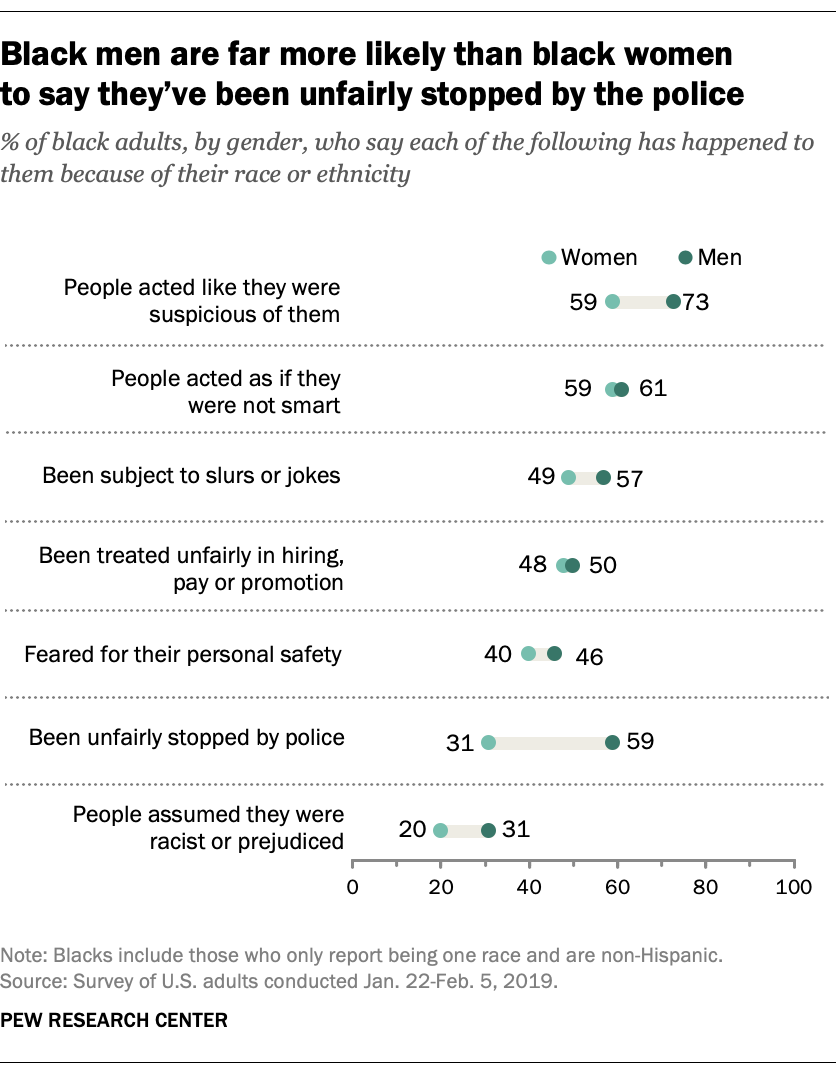

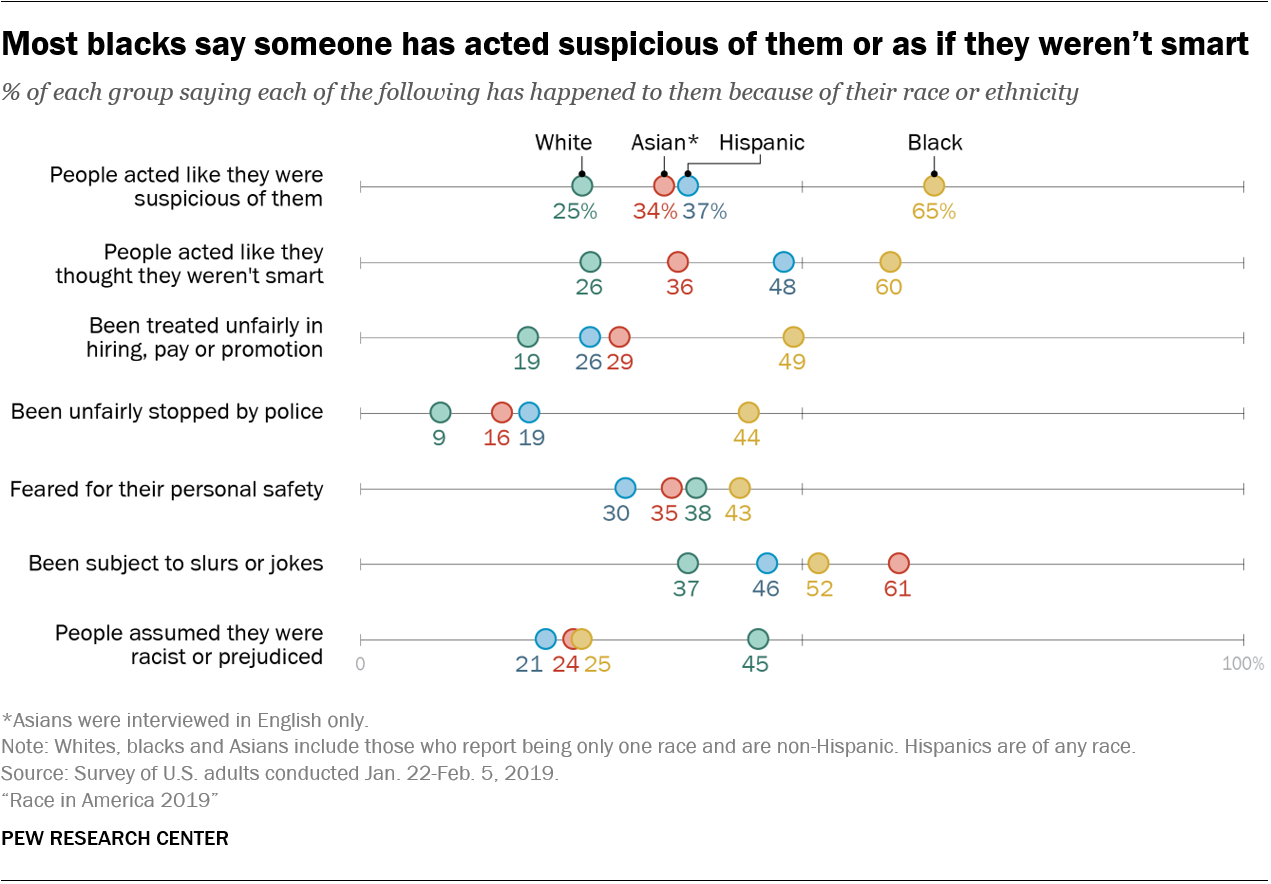

Black adults are about five times as likely as whites to say they’ve been unfairly stopped by police because of their race or ethnicity (44% vs. 9%), according to the same survey. Black men are especially likely to say this: 59% say they’ve been unfairly stopped, versus 31% of black women.

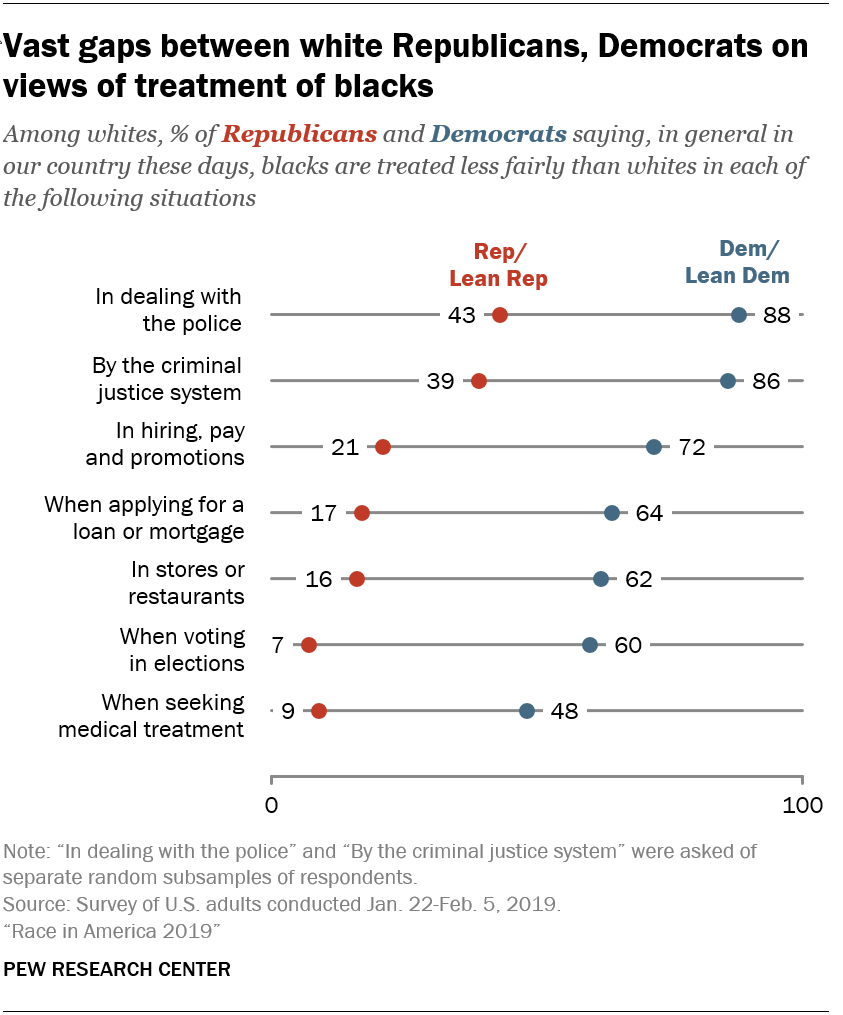

White Democrats and white Republicans have vastly different views of how black people are treated by police and the wider justice system. Overwhelming majorities of white Democrats say black people are treated less fairly than whites by the police (88%) and the criminal justice system (86%), according to the 2019 poll. About four-in-ten white Republicans agree (43% and 39%, respectively).

Nearly two-thirds of black adults (65%) say they’ve been in situations where people acted as if they were suspicious of them because of their race or ethnicity, while only a quarter of white adults say that’s happened to them. Roughly a third of both Asian and Hispanic adults (34% and 37%, respectively) say they’ve been in such situations, the 2019 survey found.

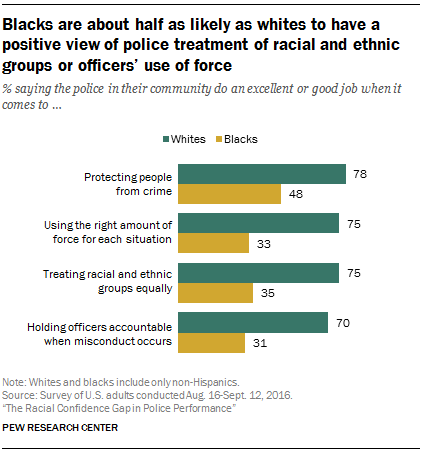

Black Americans are far less likely than whites to give police high marks for the way they do their jobs. In a 2016 survey, only about a third of black adults said that police in their community did an “excellent” or “good” job in using the right amount of force (33%, compared with 75% of whites), treating racial and ethnic groups equally (35% vs. 75%), and holding officers accountable for misconduct (31% vs. 70%).

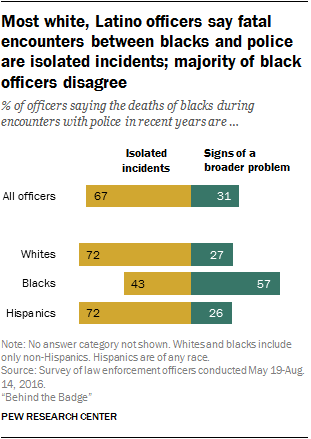

In the past, police officers and the general public have tended to view fatal encounters between black people and police very differently. In a 2016 survey of nearly 8,000 policemen and women from departments with at least 100 officers, two-thirds said most such encounters are isolated incidents and not signs of broader problems between police and the black community. In a companion survey of more than 4,500 U.S. adults, 60% of the public called such incidents signs of broader problems between police and black people. But the views given by police themselves were sharply differentiated by race: A majority of black officers (57%) said that such incidents were evidence of a broader problem, but only 27% of white officers and 26% of Hispanic officers said so.

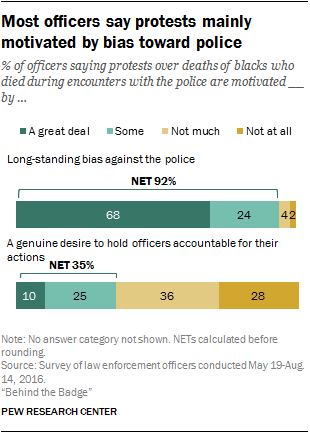

Around two-thirds of police officers (68%) said in 2016 that the demonstrations over the deaths of black people during encounters with law enforcement were motivated to a great extent by anti-police bias; only 10% said (in a separate question) that protesters were primarily motivated by a genuine desire to hold police accountable for their actions. Here as elsewhere, police officers’ views differed by race: Only about a quarter of white officers (27%) but around six-in-ten of their black colleagues (57%) said such protests were motivated at least to some extent by a genuine desire to hold police accountable.

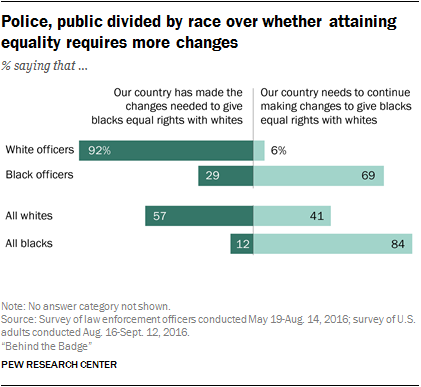

White police officers and their black colleagues have starkly different views on fundamental questions regarding the situation of blacks in American society, the 2016 survey found. For example, nearly all white officers (92%) – but only 29% of their black colleagues – said the U.S. had made the changes needed to assure equal rights for blacks.

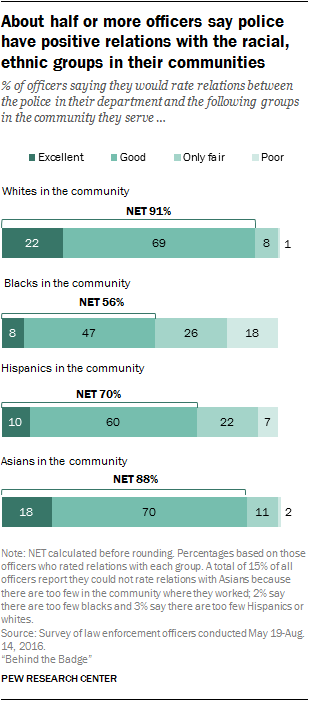

A majority of officers said in 2016 that relations between the police in their department and black people in the community they serve were “excellent” (8%) or “good” (47%). However, far higher shares saw excellent or good community relations with whites (91%), Asians (88%) and Hispanics (70%). About a quarter of police officers (26%) said relations between police and black people in their community were “only fair,” while nearly one-in-five (18%) said they were “poor” – with black officers far more likely than others to say so. (These percentages are based on only those officers who offered a rating.)

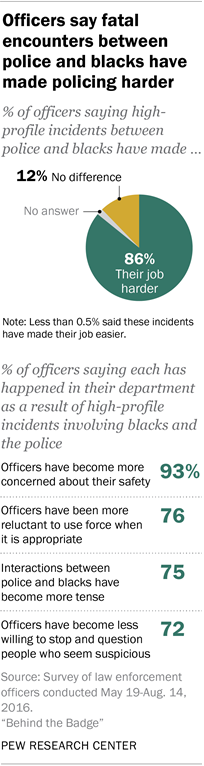

An overwhelming majority of police officers (86%) said in 2016 that high-profile fatal encounters between black people and police officers had made their jobs harder. Sizable majorities also said such incidents had made their colleagues more worried about safety (93%), heightened tensions between police and blacks (75%), and left many officers reluctant to use force when appropriate (76%) or to question people who seemed suspicious (72%).