As the U.S. battles COVID-19, effective contact tracing has proven to be a major challenge for those trying to contain the spread of the coronavirus. A new Pew Research Center report from a survey conducted July 13-19, 2020, finds that Americans hold a variety of views that could complicate the ongoing efforts of public health authorities to trace and contain the virus.

The report largely focuses on what Americans tell us they might do when faced with three key parts of the contact tracing and quarantine process amid COVID-19, which we refer to as “speak,” “share” and “quarantine”:

- How likely people say they would be to speak with a public health official who contacted them by phone or text message to speak with them about the coronavirus outbreak.

- How comfortable they say they would be sharing information about the people with whom they have been in contact and where they have been (either via places they have recently visited or location data from their cellphone).

- Whether they say they would act on advice to quarantine for 14 days if advised to do so by a public health official because they had the coronavirus.

This analysis was conducted to understand Americans’ views of the contact tracing process amid the coronavirus outbreak. It is based on a survey of 10,211 U.S. adults conducted from July 13-19, 2020. Everyone who took part is a member of Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology.

Here are the questions used for the report, along with responses, and its methodology.

While majorities of Americans say they would be comfortable or likely to engage with some parts of contact tracing programs, others express wariness. In all, 48% of U.S. adults say they would be comfortable or likely to engage with all three steps. Others might engage with some steps, but be less comfortable or willing for others. Some 36% of Republicans and those who lean toward the Republican Party say they would be comfortable or likely to engage with all three of these steps under our “speak, share, quarantine” definition of engagement, compared with six-in-ten Democrats and leaners.

Here are five key takeaways from the report:

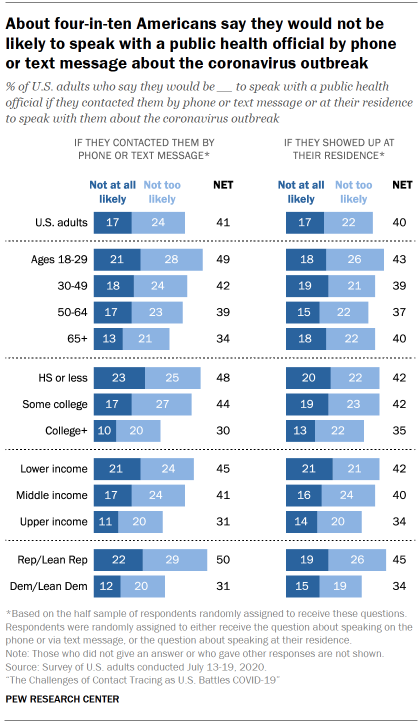

Some 41% of adults say they would not be likely to speak with a public health official by phone or text message about COVID-19. Not all Americans are equally likely to say this. For example, looking at this first step of the process only, 48% of those with a high school diploma or less formal education say they would be not at all or not too likely to speak with a public health official in this way, compared with a smaller share (30%) of those with a bachelor’s degree or higher. There are also differences by income: 45% of those from households with lower incomes say they would be not at all or not too likely to do so by phone or text, while a smaller share (31%) of those in higher-income households say the same.

Younger Americans are also less likely to say they would speak with a public health official by phone or text during the outbreak. Roughly half (49%) of adults ages 18 to 29 say they would be not at all or not too likely to do so, compared with smaller shares of Americans 50 and older who express such reluctance.

Republicans are roughly 20 percentage points more likely to express resistance to speaking with a public health official about the coronavirus: Half of Republicans say they are at most not too likely to do so, compared with 31% of Democrats.

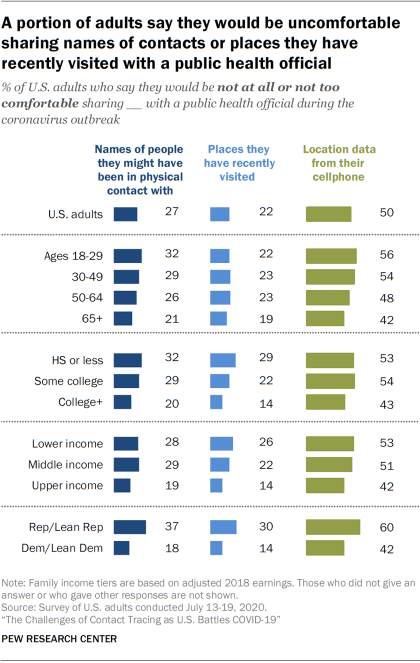

Americans’ comfort with sharing information with public health officials about whom they have been with and where they have been varies. Roughly three-in-ten U.S. adults (27%) say they would be not at all or not too comfortable sharing the names of people with whom they might have been in physical contact. A similar share (22%) say the same about their lack of comfort sharing information on places they have recently visited. Half of U.S. adults say they would be not at all or not too comfortable sharing location data from their cellphone.

Republicans are about twice as likely as Democrats to say that they would be not at all or not too comfortable sharing the names of people with whom they might have been in physical contact (37% vs. 18%) and places they’ve recently visited (30% vs. 14%). They are also more likely to express discomfort about sharing location data from their cellphone (60% vs. 42%).

Younger adults express less comfort sharing information than older adults. For instance, 32% of those ages 18 to 29 say they would be not at all or not too comfortable sharing the names of people they might have been in physical contact with, compared with 21% of those ages 65 and older who say this. And those with lower incomes and less formal education tend to be less comfortable sharing information. About three-in-ten of those from households with lower (28%) or middle incomes (29%) say they would be not at all or not too comfortable sharing names of contacts, compared with 19% of those with higher incomes who say so.

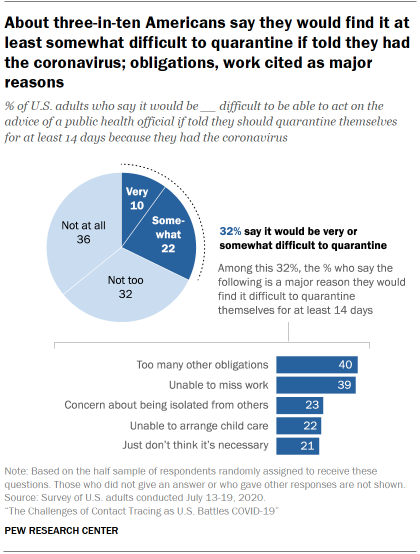

The vast majority of Americans say they would definitely or probably quarantine if told they had COVID-19, but some report it would be difficult. About nine-in-ten adults (93%) say they definitely (73%) or probably (20%) would act on the advice of a public health official to quarantine for at least 14 days because they had the coronavirus.

Although the majority of Americans who identify with either party say that they would definitely or probably quarantine (97% of Democrats and 88% of Republicans say this), Republicans are 26 percentage points less likely than Democrats to say they definitely would quarantine – some 59% of Republicans say so, compared with 85% of Democrats. Men are also less likely than women to report they would definitely quarantine (65% vs. 80%), and White adults (70%) are less likely to say this than Hispanic (80%) or Black (76%) Americans.

Further, about three-in-ten Americans (32%) say it would be very (10%) or somewhat (22%) difficult to be able to act on advice from a public health official to quarantine for at least 14 days if told they had the coronavirus. When those individuals who said it would be very or somewhat difficult to quarantine were asked about the reasons why, major reasons cited included having too many other obligations (40%) and being unable to miss work (39%).

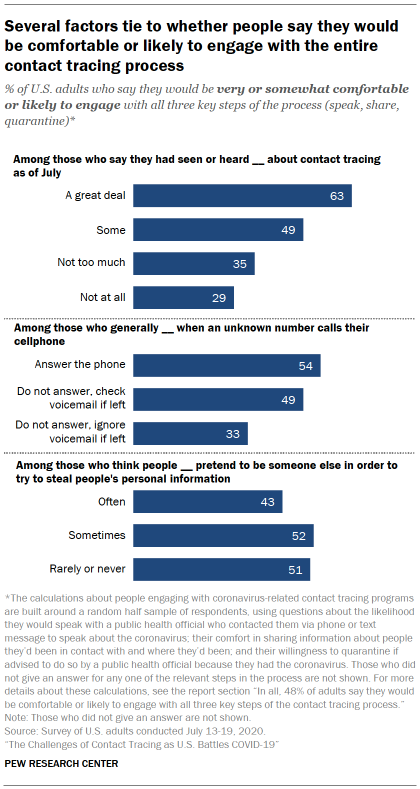

Awareness of contact tracing and perceptions of how often scams happen are linked to the steps people say they would be likely or comfortable to take in the process. Some seven-in-ten U.S. adults had seen or heard a great deal or some about contact tracing at the time this survey was taken in July, whereas three-in-ten (29%) had heard nothing at all or not too much about this process. Those who had seen or heard not much or nothing at all are least likely to say they would be comfortable or likely to engage with all three contact tracing steps explored here (“speak, share, quarantine”).

The survey also shows that just 19% of Americans report generally answering their cellphone when a call comes from an unknown number. Another 14% say they do not answer the phone and would ignore a voicemail if left. The majority of U.S. adults (67%), however, would not answer a call from an unknown number, but would check a voicemail. Those who generally ignore both a call and a voicemail from a number they do not know are also less likely to say they are comfortable or likely to engage with the three steps of the contact tracing process than others.

This wariness also applies to those who think people pretend to be someone else in order to steal others’ personal information with some frequency. Nine-in-ten Americans think people pretend to be someone else in order to try to steal people’s personal information often (49%) or sometimes (42%). Americans who think this happens often are less likely than those who think it happens less frequently to be comfortable or likely to engage with the speak, share, quarantine steps of the process in the context of the coronavirus outbreak.

Americans are more confident than not in public health organizations to keep their records safe from hackers or unauthorized users, but about four-in-ten are at most not too confident in this. In light of general privacy concerns about tech-based solutions to contact tracing, as well as new findings about general trust in public institutions, Americans were asked about their confidence in relevant organizations and institutions to keep their personal records safe in general. A majority (59%) of Americans say they are very or somewhat confident that public health organizations will keep their personal records safe from hackers or unauthorized users. Some 41% say they are not at all or not too confident in these organizations to do this.

Those who express less confidence in public health organizations to keep their personal records safe are also less likely than others to say they would be comfortable or likely to engage with all three steps of the contact tracing process. Seven-in-ten of those who are very confident that public health organizations will protect their personal records from hackers or unauthorized users also say that they would be comfortable or likely to engage with all three steps, compared with smaller shares of those who express less confidence – 56% of those who are somewhat confident, 36% of those who are not too confident, and 21% of those who are not at all confident.