Note: For the latest information on this topic, read our 2022 post.

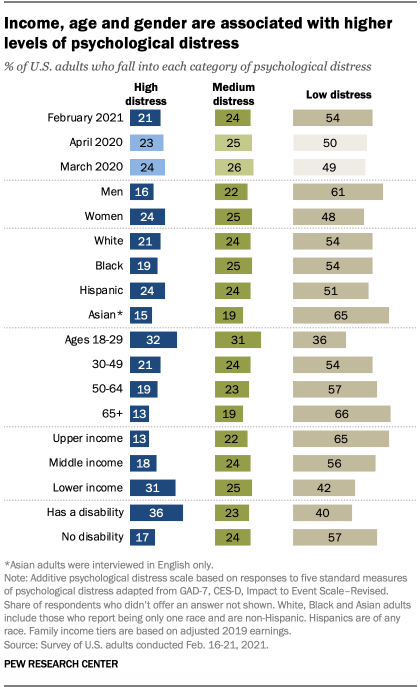

One year into the societal convulsions caused by the coronavirus pandemic, about a fifth of U.S. adults (21%) are experiencing high levels of psychological distress, including nearly three-in-ten (28%) among those who say the outbreak has changed their lives in “a major way.” The share of the public experiencing psychological distress has edged down slightly since March 2020 but remains elevated among some groups in the population. Concerns about both the personal health and the financial threats from the pandemic are associated with high levels of psychological distress.

This assessment of the public’s psychological reaction to the COVID-19 outbreak is based on surveys of members of Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP) conducted online several times since March 2020. The mental health questions were included on three surveys. The first survey was conducted with 11,537 U.S. adults March 19-24, 2020; a second survey with the question series was conducted April 20-26, 2020, with a sample of 10,139 adults; and the most recent survey was conducted Feb. 16-21, 2021, among 10,121 adults. This analysis also includes questions asked in a survey conducted Jan. 19-24, 2021, with a sample of 10,334 adults.

The ATP is an online survey panel that is recruited through national random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The surveys are weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Here is more information about the ATP.

The psychological distress index used here measures the total amount of mental distress that individuals reported experiencing in the past seven days. The low distress category in the index includes about half of the sample; very few in that group said they were experiencing any of the types of distress most or all of the time. The middle category includes roughly one-quarter of the sample, while the high distress category includes 21%, down slightly from 24% in March 2020. A large majority of those in the high distress group reported experiencing at least one type of distress most or all of the time in the past seven days.

The questions used to measure the levels of psychological distress were developed with the help of the COVID-19 and mental health measurement group from Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health (JHSPH): M. Daniele Fallin (JHSPH), Calliope Holingue (Kennedy Krieger Institute, JHSPH), Renee Johnson (JHSPH), Luke Kalb (Kennedy Krieger Institute, JHSPH), Frauke Kreuter (University of Maryland, Ludwig-Maximilians University of Munich), Elizabeth Stuart (JHSPH), Johannes Thrul (JHSPH) and Cindy Veldhuis (Columbia University).

Here are the mental health questions used for this analysis, along with responses, and the detailed survey methodology statements for March 2020, late April 2020 and February 2021.

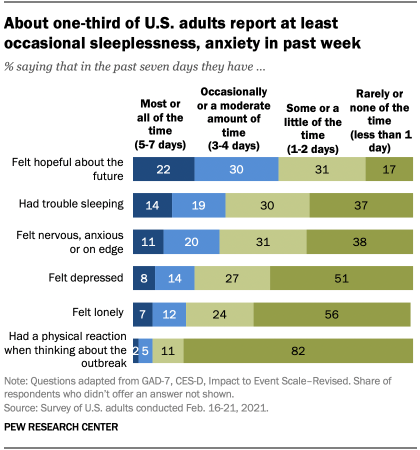

The index of psychological distress is based on a set of five questions asking about anxiety, sleeplessness, depression, loneliness and physical symptoms of distress. Except for the last item, the questions do not explicitly mention the pandemic. But experts have documented that fear and isolation associated with the pandemic have been responsible for a surge of anxiety and depression over the past year. And on the one item that asks about physical reactions when thinking about coronavirus outbreak – such as sweating, trouble breathing, nausea or a pounding heart – 17% report having such reactions at least “some or a little of the time” in the past week.

The five items were combined to create an index, which was then grouped into three categories: high, medium and low distress. The questions were part of a survey conducted online Feb. 16-21 among 10,121 members of Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel. Most of those interviewed had also participated in last year’s surveys about reactions to the pandemic.

High levels of distress are being experienced by those who say the coronavirus outbreak is a major threat to their personal financial situation (34% high distress) or to their personal health (28%). Psychological distress is especially common among adults ages 18 to 29 (32%), those with lower family incomes (31%) and those who have a disability or health condition that keeps them from participating fully in work, school, housework or other activities (36%).

The share of adults falling into the high distress group (21%) is now slightly lower than in March of last year: It was 24% then, near the beginning of coronavirus-related lockdowns in the U.S.

Underneath the relative stability of the index, considerable change has occurred. About six-in-ten (61%) of those interviewed in both April 2020 and February 2021 remained in the same category of the index. Just over a fifth (22%) moved from a higher to a lower category of distress, while 16% moved from a lower to a higher category. Of all panelists interviewed in both April 2020 and February 2021, 12% were classified as high in psychological distress in both interviews and 40% were low in both.

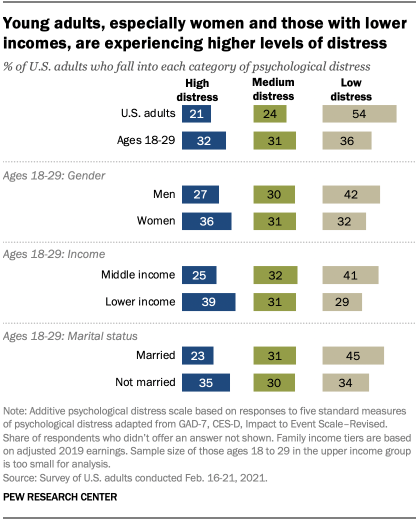

Young people have been a particular group of concern during the pandemic for mental health professionals, and young adults stand out in the current survey for exhibiting higher levels of psychological distress than other age groups. The shutdowns have disrupted job opportunities, college experiences, and the mixing and mingling that marks the transition to adulthood. Among adults ages 18 to 29, women (36%) and those with lower incomes (39%) are especially likely to be in the high distress group. In this age group, those who are unmarried fare worse than the married (35% vs. 23% experienced high levels of distress, respectively).

Adults ages 18 to 29 are especially likely to report anxiety, depression or loneliness compared with other age groups. For example, 45% of those under 30 describe being “nervous, anxious or on edge” at least “occasionally or a moderate amount of time” during the past seven days; among those 30 and older, 28% do so.

Not surprisingly, psychological distress is higher among those who express concern about becoming ill with COVID-19 or believe that the disease is a major threat to their personal health. Among those who are “very concerned” that they might get infected and require hospitalization, 27% score high in psychological distress, compared with just 14% among those who are not too or not at all concerned. Similarly, 27% of those who see the disease as a major threat to their personal health score high in psychological distress, compared with 11% who say it is not a threat. Distress levels are also higher among those who perceive the sign-up process for a coronavirus vaccine in their area as unfair or who say that it has not been easy to find information about the process.

As much as concern about the health implications of the pandemic may be affecting the mental health status of many Americans, financial troubles are also a strong correlate of psychological distress. Pew Research Center surveys, including this one, have documented the substantial negative impact of the pandemic on the financial situation of many Americans. A January survey found that more than four-in-ten adults said that they or someone in their household had lost a job or wages since the beginning of the outbreak, and significant shares of the unemployed acknowledged the emotional toll it had taken.

Among those interviewed in the current survey who say that the pandemic is a major threat to their personal financial situation, 34% are classified as being in high psychological distress. Even greater levels of distress are observed among those who said in a January interview that they worry about how to pay their bills “every day” (40% high psychological distress) or who said they are in “poor” shape financially (44%).

Note: Here are the mental health questions used for this analysis, along with responses, and the detailed survey methodology statements for March 2020, late April 2020 and February 2021.