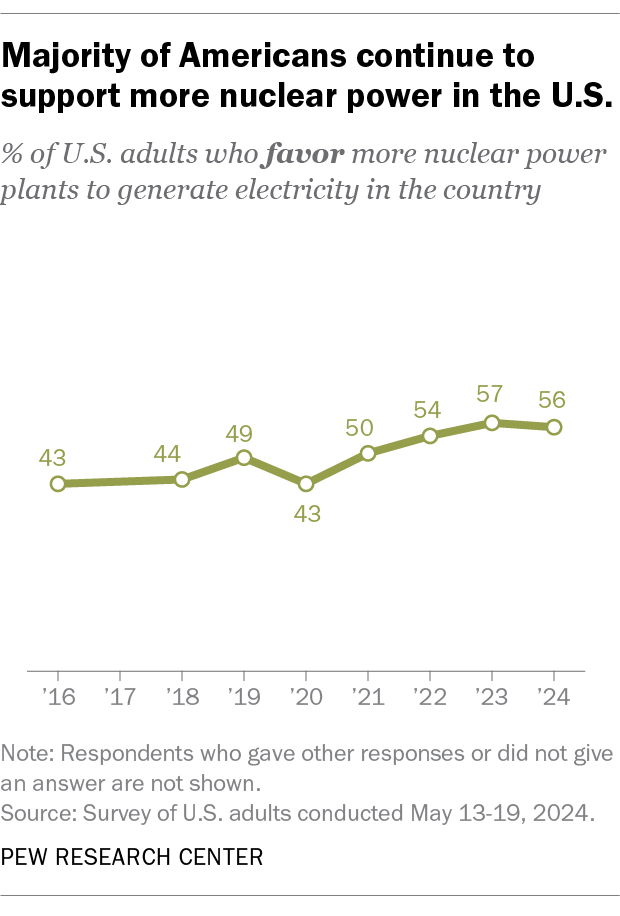

A majority of U.S. adults remain supportive of expanding nuclear power in the country, according to a Pew Research Center survey from May. Overall, 56% say they favor more nuclear power plants to generate electricity. This share is statistically unchanged from last year.

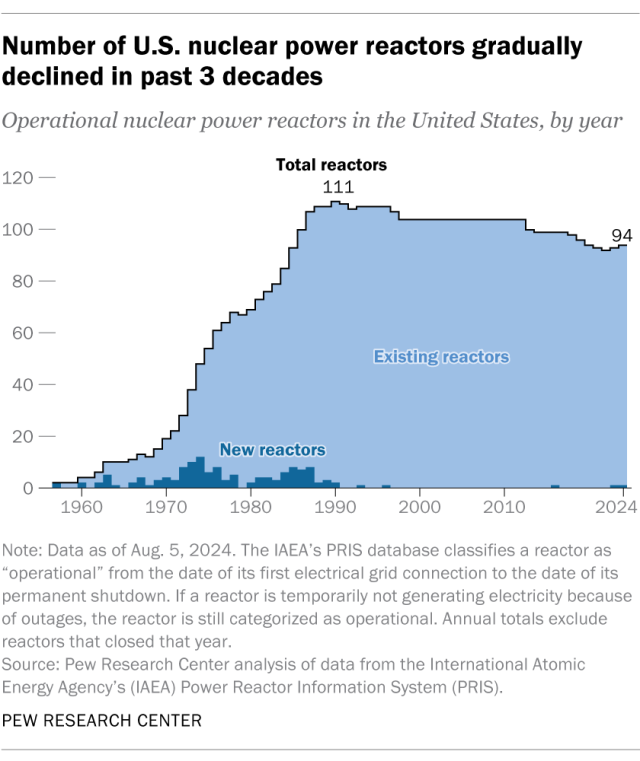

But the future of large-scale nuclear power in America is uncertain. While Congress recently passed a bipartisan act intended to ease the nuclear energy industry’s financial and regulatory challenges, reactor shutdowns continue to gradually outpace new construction.

Americans remain more likely to favor expanding solar power (78%) and wind power (72%) than nuclear power. Yet while support for solar and wind power has declined by double digits since 2020 – largely driven by drops in Republican support – the share who favor nuclear power has grown by 13 percentage points over that span.

When asked about the federal government’s role in encouraging the production of nuclear energy, Americans are somewhat split. On balance, more say the government should encourage (41%) than discourage (22%) this. But 36% say the government should not exert influence either way, according to a March 2023 Center survey.

To measure public attitudes toward the use of nuclear power in the United States, we analyzed data from Pew Research Center surveys. Most of the data comes from our survey of 8,638 U.S. adults conducted May 13-19, 2024.

Everyone who took part in the survey is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way, nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology.

Here are the survey questions used for this analysis, along with responses, and its methodology.

Links to related Center surveys, including their questions and methodologies, can be found throughout the post.

In addition, we tracked the number of U.S. nuclear power reactors over time by analyzing data from the International Atomic Energy Agency’s (IAEA) Power Reactor Information System. The IAEA classifies a reactor as “operational” from the date of its first electrical grid connection to the date of its permanent shutdown. Reactors that face temporary outages are still categorized as operational. Annual totals exclude reactors that closed that year.

Views by gender

Attitudes on nuclear power production have long differed by gender.

In the May survey, men remain far more likely than women to favor more nuclear power plants to generate electricity in the United States (70% vs. 44%). This pattern holds true among adults in both political parties.

Views on nuclear energy differ by gender globally, too, according to a Center survey conducted from fall 2019 to spring 2020. In 18 of the 20 places surveyed around the world (including the U.S.), men were more likely than women to favor using more nuclear power as a source of domestic energy.

Views by party

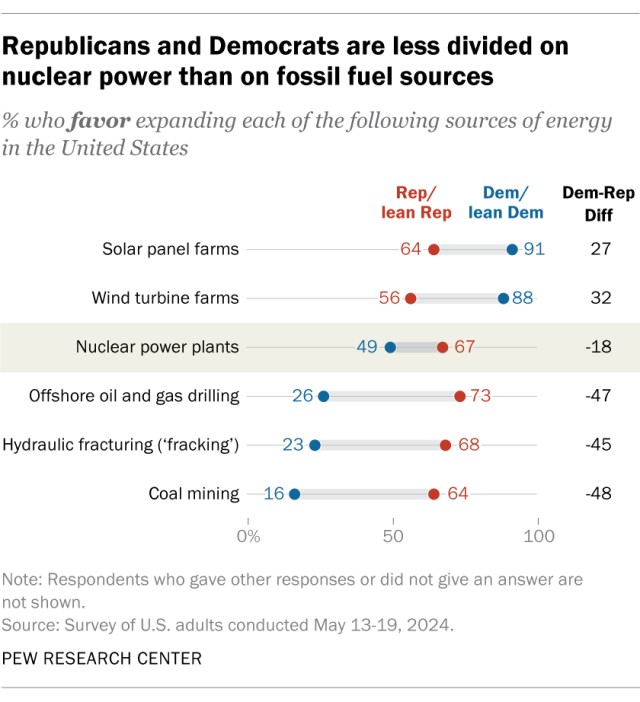

Republicans are more likely than Democrats to favor expanding nuclear power to generate electricity in the U.S. Two-thirds of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents say they support this, compared with about half of Democrats and Democratic leaners.

Republicans have supported nuclear power in greater shares than Democrats each time this question has been asked since 2016.

The partisan gap in support for nuclear power (18 points) is smaller than those for other types of energy, including fossil fuel sources such as coal mining (48 points) and offshore oil and gas drilling (47 points).

Still, Americans in both parties now see nuclear power more positively than they did earlier this decade. While Democrats remain divided on the topic (49% support, 49% oppose), the share who favor expanding the energy source is up 12 points since 2020. Republican support has grown by 14 points over this period.

While younger Republicans generally tend to be more supportive of increasing domestic renewable energy sources than their older peers, the pattern reverses when it comes to nuclear energy. For example, Republicans under 30 are much more likely than those ages 65 and older to favor more solar panel farms in the U.S. (80% vs. 54%); there’s a similar gap over expanding wind power. But when it comes to expanding nuclear power, Republicans under 30 are 11 points less likely than the oldest Republicans to express support (61% vs. 72%).

A look at U.S. nuclear power reactors

The U.S. currently has 94 nuclear power reactors, including one that just began operating in Georgia this spring. Reactors collectively generated 18.6% of all U.S. electricity in 2023, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

About half of the United States’ nuclear power reactors (48) are in the South, while nearly a quarter (22) are in the Midwest. There are 18 reactors in the Northeast and six in the West, according to data from the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

The number of U.S. reactors has steadily fallen since peaking at 111 in 1990. Nine Mile Point-1, located in Scriba, New York, is the oldest U.S. nuclear power reactor still in operation. It first connected to the power grid in November 1969. Most of the 94 current reactors began operations in the 1970s (41) or 1980s (44), according to IAEA data. (The IAEA classifies reactors as “operational” from their first electrical grid connection to their date of permanent shutdown.)

Within the last decade, just three new reactors joined the power fleet. Three times as many shut down over the same timespan.

One of the many reasons nuclear power projects have dwindled in recent decades may be the perceived dangers following nuclear accidents in the U.S. and abroad. For example, the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi accident led the Japanese government to greatly decrease its reliance on nuclear power and prompted other countries to rethink their nuclear energy plans. High construction costs and radioactive waste storage issues are also oft-cited hurdles to nuclear energy advancement.

Still, many advocates say that nuclear power is key to reducing emissions from electricity generation. There’s been a recent flurry of interest in reviving decommissioned nuclear power sites, including the infamous Three Mile Island plant and the Palisades plant, the latter of which shuttered in 2022. Last year, California announced it would delay the retirement of its one remaining nuclear power plant until 2030. And just this summer, construction began on a new plant in Wyoming. It’s set to house an advanced sodium-cooled fast reactor, pending approval from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

Note: Here are the questions used for the analysis, along with responses, and its methodology. This is an update of a post first published March 23, 2022.