This fall’s midterm elections could make the next Congress look very different from the current one. Redistricting changes and a slew of retirements mean there will be dozens of new faces on Capitol Hill come Jan. 3 – aside from the question of which party will control the new House and Senate.

Then again, Congress’ membership turns over a lot faster than many people might realize, especially if their image of the national legislature is set by top leaders like House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (82 years old, in the House since 1987) and Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (80 years old, first elected to the Senate in 1984, and the 15th-longest-serving senator ever). Those high-profile, long-tenured lawmakers are more the exception than the rule.

Pew Research Center conducted this analysis in advance of this year’s midterm elections in order to get an idea of how much turnover in congressional membership is normal. We decided to look at the subject from three different angles.

To understand how much turnover there is in the U.S. House of Representatives during each election cycle, we examined election results going back to 1992 (building on previous work we’ve done on incumbents who don’t seek reelection). Because all House seats are up every two years, focusing on the House in this portion of the analysis allows for more straightforward comparisons from one election cycle to another.

Next, we wanted to examine turnover over a longer period. We settled on comparing Congresses 12 years apart, because that equates to six complete House terms or two complete Senate terms. We relied on the Biographical Directory of the U.S. Congress for dates of service, and on the congressional rosters compiled by voteview.com.

To make the comparisons as clean as possible, we compared membership of the House and Senate on the opening day of each Congress to the opening-day roster of the Congress 12 years earlier. Members who were on both rosters were coded as “holdovers.” Subtracting the holdovers from the total voting memberships of the House (435) and Senate (100) gave us the number of “turnover” seats, and dividing the turnover figure by the total membership yielded the 12-year turnover rate.

Finally, we wanted to sort the current House and Senate members by how long they’d served in those positions – including, in a handful of cases, earlier stints in the same chamber. In most cases, determining when someone’s congressional service began was straightforward, but it became trickier in cases of special elections or when senators were appointed to fill vacancies. Ultimately, we deferred to the start dates listed in the Congressional Directory, the most recent online edition of which covers the 116th Congress. For more recently elected members, we relied on the start dates listed in the Biographical Directory.

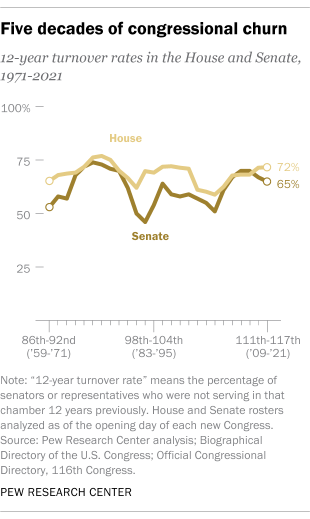

In fact, when the current Congress convened in January 2021, 72% of House members and 65% of senators were new since the start of the 111th Congress in January 2009 – what we call the “12-year turnover rate.”

That degree of turnover isn’t unusual. Over the past five decades, the average 12-year turnover rate – that is, the share of seats held by different occupants between two Congresses a dozen years apart – is 69% in the House and 62% in the Senate, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of House and Senate membership rosters since the early 1970s.

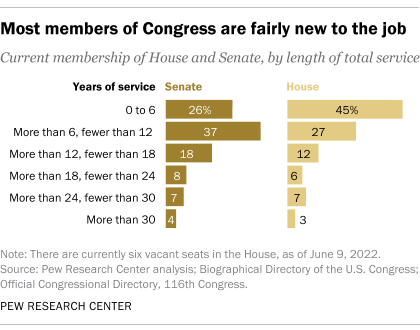

Looked at another way, among the members of Congress as of June 9, about 70% of representatives (307) and nearly two-thirds of senators (63%) have held their offices for less than 12 years – equivalent to two full Senate terms or six full House terms.

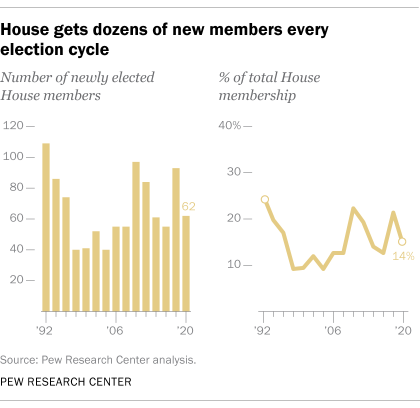

It’s true that, in any given election cycle, most members of Congress who seek new terms are reelected. In 2020, for example, 373 of the 394 House members who ran for reelection, or nearly 95%, won.

But a total of 62 House seats did change hands between the end of the last Congress and the start of this one, as members retired, sought other offices (including Senate seats), resigned early to take new jobs, lost their reelection bids or, in a few cases, died. That was about 14% of the whole House, a bit below the long-term average turnover rate from one Congress to the next: Over the past 30 years, House turnover between consecutive Congresses has ranged from 40 members (9%) to 109 (25%).

Even in periods of relatively low congressional turnover, though, it doesn’t take long for the changes to accumulate.

To arrive at these figures, the Center looked at each Congress from the 92nd (1971-72) to the present and compared their opening-day rosters with those of the Congress 12 years prior. The 12-year turnover rate in the House never fell below 59% or exceeded 77%; in the Senate, it ranged from 46% to 74%.

Turnover peaked in the late 1970s and early 1980s, as dozens of long-serving senators and representatives either died or were defeated. In five straight Congresses, from the 96th (1979-80) to the 100th (1987-88), the 12-year turnover rate was 70% or greater in both the House and Senate – meaning that, in each of those Congresses, no more than three-in-ten members had been in that chamber 12 years earlier.

These turnover rates may seem to be at odds with the fact that Congress is, on average, getting older. A Center analysis from 2021 found that the median ages of both senators and representatives have been moving higher, to 64.8 and 58.9 years old, respectively.

But age and political experience aren’t necessarily related. And while the term “freshman” connotes youth and inexperience, many first-term senators and representatives come to Capitol Hill with a lifetime of experience in government, business or other fields. For example:

- Democratic Sen. John Hickenlooper is a 70-year-old “freshman.” He had two terms as Colorado’s governor under his belt when he ran for the Senate in 2020, and eight years as Denver’s mayor before that.

- Republican Sen. Bill Hagerty of Tennessee, age 62, co-founded a private-equity firm, served in state government, and was ambassador to Japan before winning his seat in 2020.

- Republican Rep. Jerry Carl of Alabama was elected at age 62, following a long business career and eight years as a Mobile County commissioner.

These turnover trends appear likely to continue. Seven senators have decided not to run for reelection, including some of the longest-serving: Democrat Patrick Leahy of Vermont (age 82, first elected in 1974); Republican Richard Shelby of Alabama (88, in office since 1987); and Republican James Inhofe of Oklahoma (87, in office since 1994). The retirees also include two-term Sens. Roy Blunt, R-Mo.; Rob Portman, R-Ohio; and Pat Toomey, R-Pa.; as well as three-term Republican Sen. Richard Burr of North Carolina.

On the House side, 33 members have decided to retire, and 17 are running for other offices. With primary season now in full swing, at least four incumbents already have lost their renomination bids. In six seats that currently are vacant due to death or resignation, new representatives will be chosen in special elections later this summer; they will join six who won their seats in special elections last year. All that means a minimum of 66 new faces on Capitol Hill next year – assuming no incumbents lose their seats, which seems unlikely.

At least some of the churn this year is being driven by redistricting following the 2020 census. The once-a-decade process has shifted some representatives into new, and not necessarily friendly, territory. In other cases, it’s left two representatives in the same district, making for some awkward primaries and not-entirely-voluntary retirements.