The aging of populations raises concerns about the affordability of publicly funded pension and health care programs in the future. Many developed economies already expend a sizable share of their GDP on these programs. For example, public expenditures on pensions and health care currently consume about 13% of GDP in the U.S. and in excess of 20% in France. For these economies, the pressing question is whether population aging will push public pensions and health care programs to consume ever-rising proportions of national income.38

Emerging economies typically do not have expansive public pension and health care programs. India and Indonesia, for example, each spend only 2% of their GDP on these programs. The challenge for these economies is to build their social insurance programs to meet the needs of their increasingly older populations and to do so in a fiscally sound manner.

In addition to increased demand for old-age financial and medical support, aging raises the possibility that per capita output sags with relatively fewer people in the workforce. These trends are unfolding in a climate of health-cost inflation that has risen faster than general inflation for several decades in most countries. However, an increase in public expenditures on pensions and health care as a share of national income is not inevitable. Future improvements in technology and gains in productivity, containment of health-cost inflation and delayed retirements may generate sufficiently large countervailing forces to slow this growth in spending.

This section reviews evidence on what governments are currently spending on public pensions and health care and the degree to which those amounts are projected to rise by 2050. The focus is on the 18 countries for which data are available on current and projected public expenditures on pensions and health care. In these countries, public expenditures on pensions and health care are generally expected to rise as a share of GDP. By and large, health care expenditures are expected to increase at a faster pace than expenditures on pensions. However, aging is not the principal driver of growth in public health care expenditures in the long run. Other factors, such as cost inflation, loom larger in many countries.

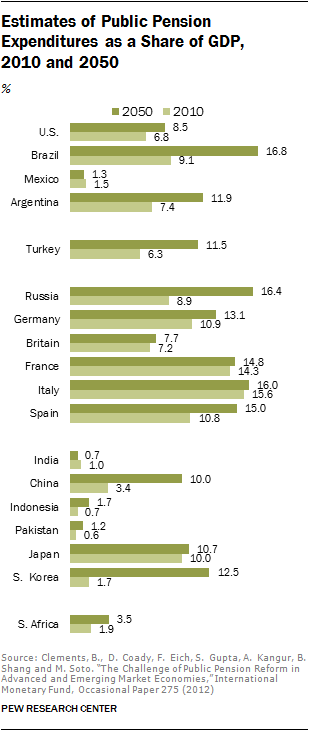

Public Pension Expenditures

Public expenditures on pensions tend to be higher in developed economies. Italy leads the pack among the countries included in this report, spending 15.6% of its GDP in 2010 on public pensions. France spent 14.3% of its GDP on public pensions, followed by Germany (10.9%), Spain (10.8%) and Japan (10.0%). The U.S. spent 6.8% of its GDP on public pension schemes in 2010, less even than Brazil (9.1%) and Argentina (7.4%).39 Government expenditures on pensions were in the order of 1% to 2% of GDP in Mexico, India, Indonesia, Pakistan, South Korea and South Africa.

Pension expenditures in developed economies are higher partly because they have older populations and partly because they provide more generous benefits. The share of the population ages 65 and older in 2010 was the highest in the U.S., Japan and European nations. Pension payments also generally replace a greater share of average wages in these countries. This “replacement rate” is about 40% in the U.S. and is higher still in France, Germany, Italy and Spain. Replacement rates in Russia, Argentina and Brazil, among the leading emerging economies, match or top the rates in the U.S. In India, Pakistan, China, Indonesia and Mexico, whose populations are relatively young, replacement rates are lower. South Korea also has a relatively low replacement rate, on par with India at about 10%.

Public pension expenditures as a share of GDP are projected to rise from 2010 to 2050 in all countries except Mexico and India.40 South Korea and China, among the countries with the most rapidly increasing median age, are expected to experience the sharpest increases in public pension expenditures—from 1.7% of GDP in 2010 to 12.5% in 2050 in South Korea and from 3.4% to 10.0% over the same period in China. Expenditures, as a share of GDP, are projected to nearly double and climb above 15% in Brazil and Russia. Turkey and Argentina are also likely to cross the double-digit threshold in pension expenditures by 2050.

However, projected increases in pension expenditures are modest in the U.S., Japan and European countries other than Russia. In the U.S., for example, public pension spending rises from 6.8% of GDP in 2010 to 8.5% in 2050. Projected increases in spending are comparably small in Germany, Britain, France, Italy, Spain and Japan.41

The expected rise in pension expenditures is lower among the developed economies because they are currently aging up at a less rapid pace and because many have implemented reforms that are expected to limit the growth in pension expenditures. In the U.S., for example, the original Social Security full retirement age of 65 has been gradually on the rise since 1983. It is scheduled to level off at 67 for people born after 1959.42 The age for receiving a pension is also set to increase in France, Italy, Spain, Britain and Japan. Other reforms limiting pension spending include changes in replacement rates and indexation rules. Meanwhile, Argentina, Brazil and China are among countries adopting more generous pension policies. Reforms introduced in South Korea starting in 1988—expanding coverage and raising replacement rates—are expected to result in sharp increases in public pension expenditures in the future.43

Overall, future increases in pension spending, as projected by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), are driven mostly by the rate at which a country is aging. Countries that are currently older but in which the pace of aging has slowed—the U.S., Germany, Italy, Britain, France and Japan—should experience relatively smaller increases in public pension expenditures. Countries whose populations are currently young but are entering a more rapid phase of aging—China, Indonesia, Brazil, Turkey and Egypt—are expected to experience a faster rate of increase in public pension spending.

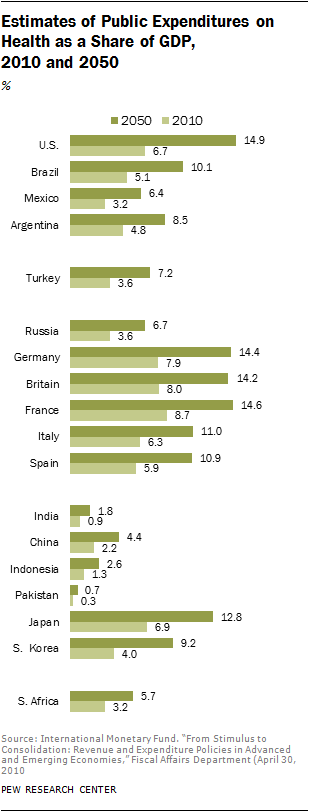

Public Health Expenditures

Governments in most countries currently spend about as much of their resources on health care as they do on pensions, or a bit less. Once again, the older, more developed economies lead the way. France committed 8.7% of GDP in 2010 to public health care expenditures, followed closely by Britain (8.0%) and Germany (7.9%). The U.S., Japan, Italy and Spain spent about 6% to 7% of their national incomes on public health care.

Public health expenditures in the other countries ranged from about 1% to 5% of GDP. Pakistan (0.3%), India (0.9%) and Indonesia (1.3%) spent the lowest share of their national incomes on public health care. Russia and Turkey (both at 3.6%) were topped by Argentina (4.8%) and Brazil (5.1%).

Expenditures on public health care are a function of the eligible population, the generosity of benefits and the cost of health care. As a rule of thumb, the more developed economies have older populations, provide more benefits and face higher cost of health care delivery. It is not surprising, therefore, that these countries also devote a greater share of their national incomes on public health care.

Projections of health care expenditures indicate significant increases in government outlays are in the cards for most countries. Spending in the U.S. is projected to more than double, from 6.7% of GDP in 2010 to 14.9% in 2050. That would put the U.S. at or above the spending share projected for France (14.6%), Germany (14.4%) and Britain (14.2%). Spending as a share of GDP may also cross into double digits in Japan (12.8%), Italy (11.0%), Spain (10.9%) and Brazil (10.1%).

Spending will remain relatively modest in other countries, but many of them are also likely to find that health care in 2050 is consuming at least twice as much as it did in 2010. In India, for example, expenditures are projected to double from 0.9% of GDP in 2010 to 1.8% in 2050. Equivalent growth is anticipated for Mexico, Turkey, China, Indonesia, Pakistan and South Korea.

Overall, the projected trends in public health expenditures point to sharp increases in all countries. The median age in European countries, for example, is not increasing nearly as fast as, say, in India or China, but European countries are not spared from significant growth in health care spending. That is because health-cost inflation is a significant driver of future increases in health care spending, perhaps even more so than aging.

For the U.S., the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has estimated that aging is of concern in the mid-term but that health-cost inflation is the principal cause of long-term growth in health expenditures. More specifically, the CBO estimates that aging is responsible for 60% of the projected increase in health care spending between 2012 and 2037 and higher costs are responsible for 40%. However, beyond 2037, rising costs are expected to be the dominant factor.44 Likewise, in its sample of advanced and emerging economies, the IMF has estimated that demographic factors account for less than half of the projected increase in health care spending through 2050.45

The upshot is that aging per se is less of a factor in increasing health expenditures than it is in raising pension expenditures. Although great variation exists in how much countries are aging, there is less variation in how much health care spending is projected to increase across countries. For example, the share of the population ages 65 and older is expected to increase by about 200% or more in China, Mexico, Brazil, Turkey and Indonesia, but it is projected to increase by about only 50% in Britain, Germany and France. However, health care spending is expected to increase within a narrower band across these countries—by about 100% in China, Mexico, Brazil, Turkey and Indonesia and by about 70% to 80% in Britain, Germany and France.