Unfavorable views of China also hover near historic highs in most of the 17 advanced economies surveyed

This analysis focuses on public opinion of China in 17 advanced economies in North America, Europe and the Asia-Pacific region. Views of China, its president and its respect for the personal freedoms of its people are examined in the context of long-term trend data.

For non-U.S. data, this report draws on nationally representative surveys of 16,254 adults from March 12 to May 26, 2021. All surveys were conducted over the phone with adults in Canada, Belgium, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, the UK, Australia, Japan, New Zealand, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan.

In the United States, we surveyed 2,596 adults from Feb. 1 to 7, 2021. Everyone who took part in the U.S. survey is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way, nearly all adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories.

This study was conducted in places where nationally representative telephone or online surveys are feasible. Due to the coronavirus outbreak, face-to-face interviewing is not currently possible in many parts of the world.

To account for the fact that some publics refer to the coronavirus differently, in South Korea, the survey asked about the “Corona19 outbreak.” In Japan, the survey asked about the “novel coronavirus outbreak.” In Greece, the survey asked about the “coronavirus pandemic.” In Australia, Canada, New Zealand and Taiwan, the survey asked about the “COVID-19 outbreak.” All other surveys used the term the “coronavirus outbreak.”

In Taiwan, questions were asked about “mainland China.”

Here are the questions used for the report, along with responses. See our methodology database for more information about the survey methods outside the U.S. For respondents in the U.S., read more about the ATP’s methodology.

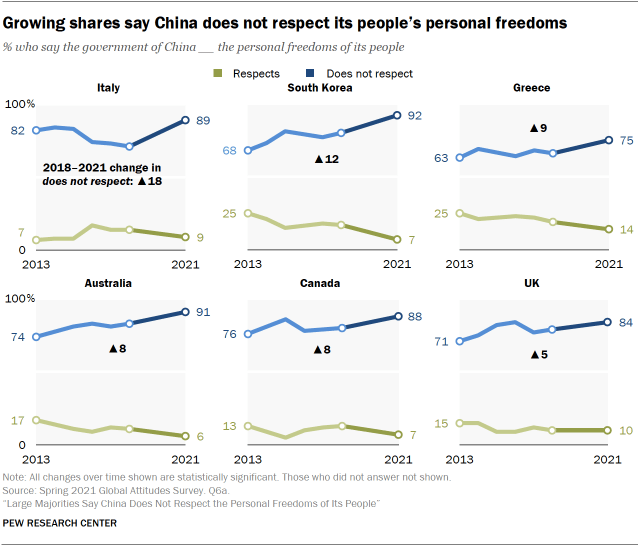

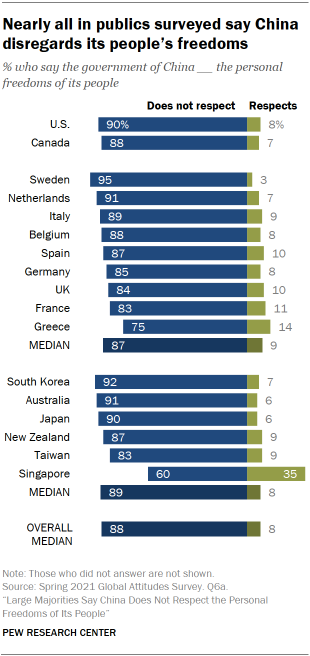

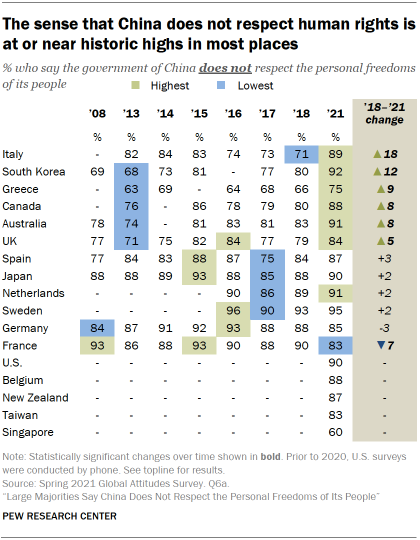

Across advanced economies in Europe, North America and the Asia-Pacific region, few people think the Chinese government respects the personal freedoms of its people. In 15 of the 17 publics surveyed by Pew Research Center, eight-in-ten or more hold this view. This sense is also at or near historic highs in nearly every place surveyed, having risen significantly in countries like Italy, South Korea, Greece, Australia, Canada and the United Kingdom since 2018.

In the United States – where trend data is not available on this question – 90% say Beijing does not respect individual liberties, including 93% of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents and 87% of Democrats and Democratic leaners.

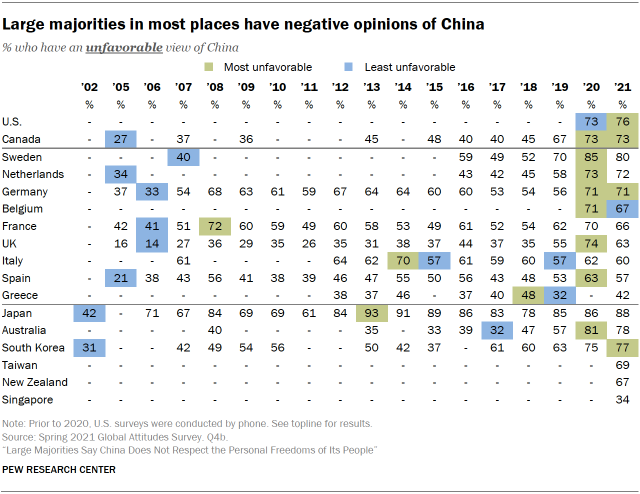

Coupled with this, unfavorable views of China are also at or near historic highs. Large majorities in most of the advanced economies surveyed have broadly negative views of China, including around three-quarters or more who say this in Japan, Sweden, Australia, South Korea and the U.S. However, unfavorable views have remained largely unchanged since 2020, as much of the negative increase in countries such as Australia, Sweden, the UK and Canada came last year in the wake of various bilateral tensions as well as a widespread sense that China handled the COVID-19 pandemic poorly. To the degree that views have shifted at all, unfavorable views have decreased somewhat in the UK (down 11 percentage points).

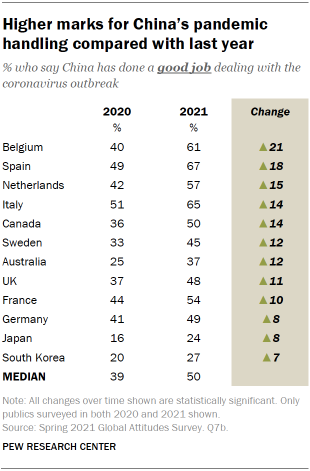

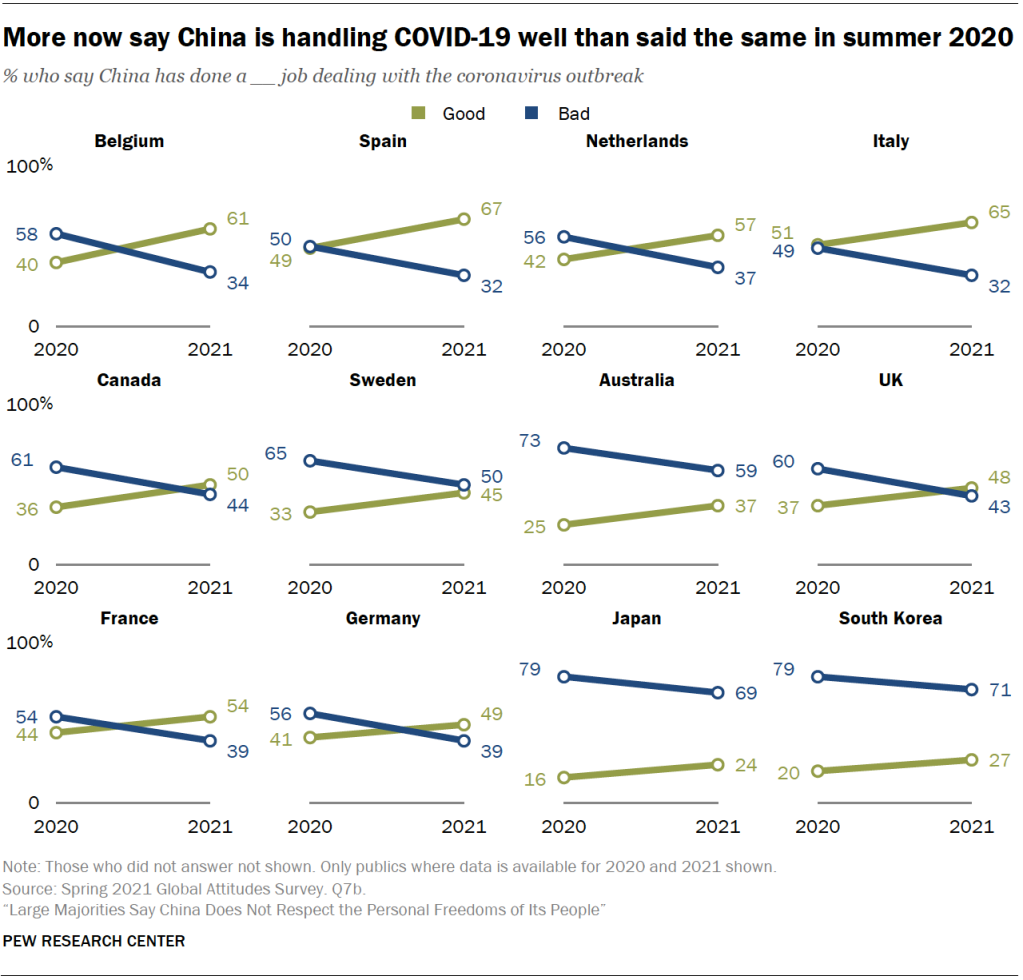

Although negative views of China remain widespread, in many advanced economies, assessments of China’s handling of COVID-19 have improved precipitously. Today, a median of 49% say China has done a good job dealing with the global pandemic, compared with a median of 43% who say it has done poorly. In each of the 12 countries surveyed in both summer 2020 and 2021, the share approving of China’s response has increased significantly, and, in places like Belgium, Spain and the Netherlands, it has gone up by at least 15 percentage points (U.S. 2020 data is omitted due to a survey mode change). And, as was the case last summer, more say China is handling the pandemic well than say the same of the U.S. Only in Japan do more compliment the U.S.’s approach to the pandemic than China’s (in the U.S., evaluations of the two countries are about equal).

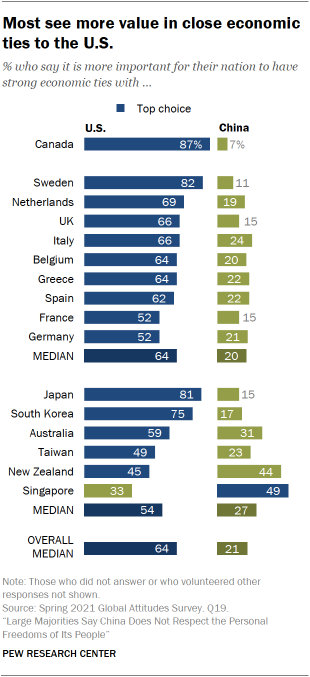

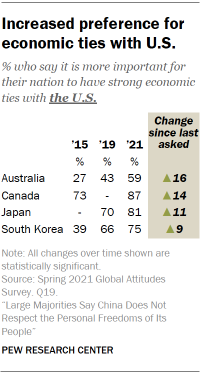

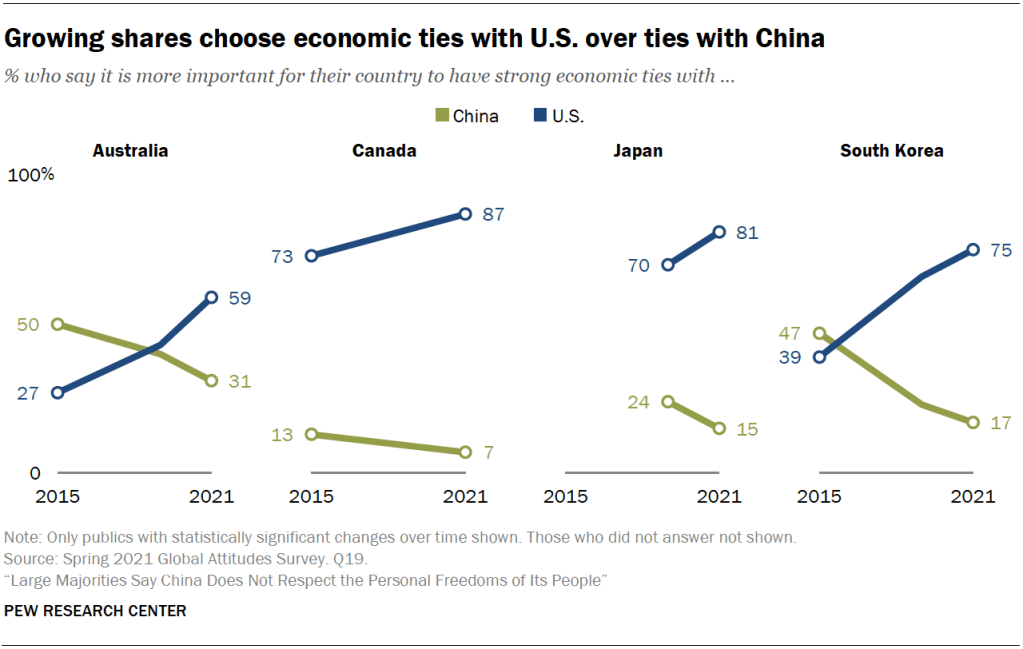

There is widespread preference for stronger economic ties with the U.S. over China. In most advanced economies surveyed, a majority – and often a wide majority – say it is more important for these economies to have strong economic ties with the U.S. than with China. In nations where this question has been asked more than once – Australia, Canada, Japan and South Korea – the importance placed on ties with the U.S. has also grown substantially in recent years. Only in Singapore and New Zealand do about as many or more say relations with China are as important for their country as with the U.S.

These are among the findings of a new Pew Research Center survey, conducted from Feb. 1 to May 26, 2021, among 18,850 adults in 17 advanced economies. Other key findings include:

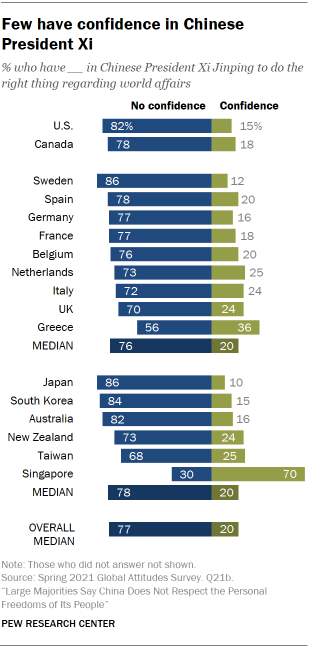

- Few have confidence in Chinese President Xi Jinping to do the right thing in world affairs. These negative evaluations of him are at or near historic highs in most places surveyed.

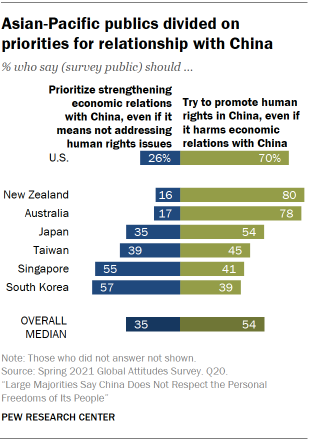

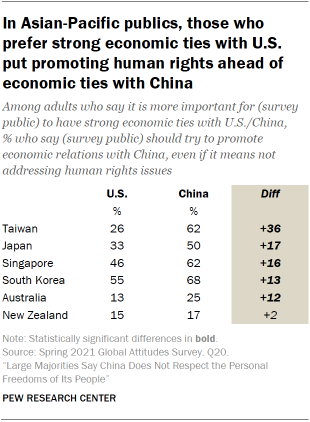

- Across the Asia-Pacific region, opinions are mixed about whether it is more important to try to promote human rights in China, even if it harms economic relations with China, or whether it’s more important to prioritize strengthening economic relations with China, even if it means not addressing human rights issues. While a majority in New Zealand (80%), Australia (78%) and Japan (54%) prioritize promoting human rights, as well as a plurality in Taiwan (45%), majorities in South Korea and Singapore prioritize strengthening economic relations. Those who prioritize economic relations with the U.S. over China tend to be much more likely to support promoting human rights.

- Europeans approve of China’s handling of COVID-19 much more than those in the Asia-Pacific. Europeans also overwhelmingly consider strong economic ties with the U.S. as more important than strong ties with China, while Asian-Pacific publics are more divided.

- In both Taiwan and Singapore, ethnic and national identity plays a role in attitudes. In Taiwan, those who identify as Chinese and Taiwanese (rather than as only Taiwanese) tend to prioritize economic relations with China over the U.S. and to have more favorable views of the superpower, among other differences. In Singapore, similar differences emerge between ethnic Chinese and ethnic Malay or Indians.

- Older adults are often more critical of China than younger ones – whether it comes to favorability of China, assessments of President Xi, evaluations of how well China has handled the COVID-19 pandemic or opinions about whether China respects the personal freedoms of its people. Older adults also tend to prefer economic ties with the U.S. over China more than younger adults. Patterns are sometimes reversed in South Korea, Taiwan and Singapore, however, with older adults offering more positive evaluations of China on some questions.

A note on the U.S. data

Starting in 2021, Pew Research Center began conducting the U.S. portion of its annual Global Attitudes survey on the Center’s American Trends Panel, a nationally representative online panel of adults. This panel is now the Center’s principal source of data for U.S. public opinion research.

Using the panel offers numerous benefits, including the ability to look at individual opinion change over time and the ability to ask questions with pictures. However, as teams across the Center have found, shifting the mode of the survey – from phone to web – can introduce challenges for trend analysis. We reported on this previously when it comes specifically to Americans’ views of China.

In this report and in others going forward, U.S. trend data from phone surveys will only appear in graphics and the topline when researchers have determined that there are no significant mode differences (aided by concurrent phone and ATP surveys in spring 2020), or it will appear with a note or dotted line, as appropriate.

The cross-country comparisons we report may also be affected because of mode differences. Most notably, on the phone, respondents are able to say that they do not know the answer to a question or, at times, to “volunteer” a response (e.g., when we asked about whether the U.S. or China should be the leading superpower in the world, we coded those who volunteered “both” or “neither”). Online, there is not an explicit “don’t know” response. And, while respondents can skip a question if they do not have an opinion, because “don’t know” is not an explicitly written choice on the screen, the percent saying “don’t know” tends to be lower than on phone surveys, where interviewers are able to code the volunteered reply. Additionally, because the U.S. survey is conducted online, it is self-administered, whereas in all other survey publics, it is interviewer-administered. For questions that are sensitive or involve people wanting to present themselves in a certain way to an interviewer (e.g., when asked about their religiosity), differences may occur across modes. Where appropriate, researchers will highlight how mode differences may affect cross-country comparisons between the U.S. and other countries included in the survey.

For more, see here.

Unfavorable views of China remain near historic highs in most advanced economies

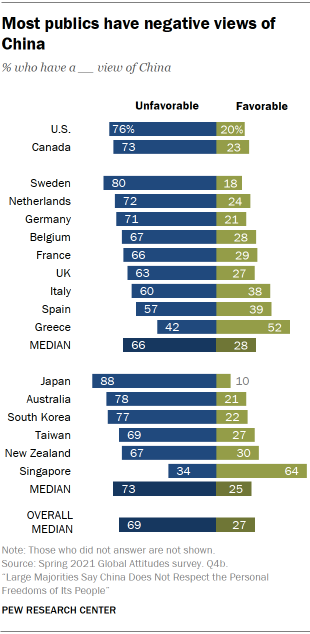

A 17-public median of 69% have an unfavorable opinion of China. In North America, roughly three-quarters of those in Canada and the U.S. hold negative views of China, including nearly four-in-ten who have very unfavorable opinions.

In Europe, a median of 66% have negative views of China, while 28% see China favorably. Majorities in eight of the nine European countries surveyed have unfavorable views of China, ranging from 80% in Sweden to 57% in Spain. Only in Greece are attitudes positive toward China, with 52% favorable and 42% unfavorable.

In the Asia-Pacific region, a median of 73% see China in a negative light, though the greatest variance in opinions exists in this region. The most negative views of China are in Japan, where roughly nine-in-ten see China negatively, including nearly half who see China very unfavorably. Two-thirds or more in Australia, South Korea, Taiwan and New Zealand likewise hold mostly negative views of China.

In Singapore, on the other hand, more than six-in-ten see China favorably. Singaporeans who self-identify as ethnic Chinese have much more favorable views of China than ethnic Malays or Indians: 72% compared with 45% and 52%, respectively.

Age sometimes plays a role in how people view China. In six publics, those ages 65 and older are more likely than those ages 18 to 29 to hold unfavorable views of China. This is especially true in Canada, where 83% of older people see China in a negative light, versus just 54% of younger Canadians who share that opinion. This pattern is reversed, however, in Taiwan and South Korea. In South Korea, for example, 67% of adults 65 and older hold an unfavorable opinion of China, compared with 84% of those ages 18 to 29.

In several of the publics included in this survey, unfavorable views of China reached historic highs in either 2020 or 2021. This is the case in Canada, five European countries and three publics in the Asia-Pacific region. In some places, unfavorable views of China rose sharply after 2018, though these views have continued to rise in recent years as well.

The Center’s polling on cross-national views of China dates back to as early as 2005 in several countries throughout Europe. In each European nation surveyed in 2005 or 2006 that was also surveyed in 2021, negative opinions of China were at their lowest in 2005 or 2006. In each of those countries, unfavorable attitudes are now at least 20 percentage points higher than about 15 years ago.

Few think China respects the personal freedoms of its people

In each of the 17 advanced economies surveyed, a majority – and in many cases a large majority – agrees that the government of China does not respect the personal freedoms of its people. In Sweden, South Korea, Australia, the Netherlands, the U.S. and Japan, at least nine-in-ten or more hold this opinion. Singapore stands out as the place where fewest hold this view – and even there, 60% say China does not respect the personal freedoms of its people.

The sense that China does not respect the personal freedoms of its people is also at or near historic highs in most publics surveyed. And, even as majorities in all countries surveyed in 2018 already believed that China does not respect the personal freedoms of its people, this sense has nonetheless gone up sharply in Italy (+18 percentage points), South Korea (+12), Greece (+9), Canada (+8), Australia (+8) and the UK (+5). Only in France has opinion shifted in the opposite direction, though 83% of French people still believe China does not respect the personal freedoms of its people.

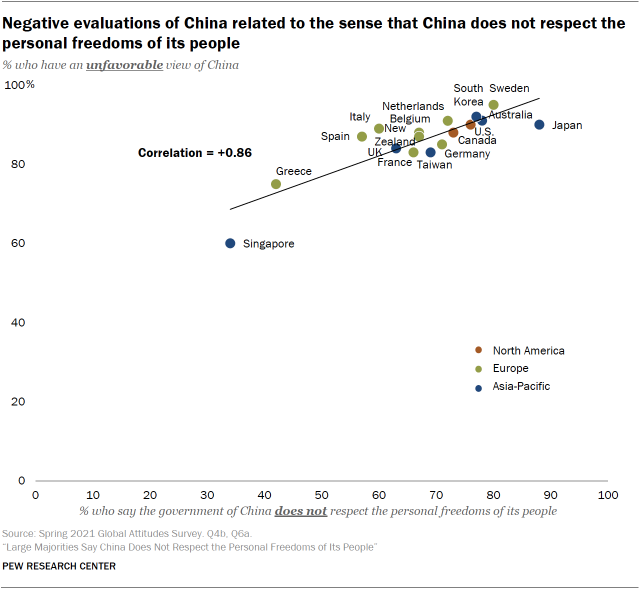

Opinions about China’s treatment of its people and views of China are closely related: In publics where more people think China does not respect its citizenry, unfavorable views of the country are higher.

In about half of the publics surveyed, those with higher levels of education are more likely to say China does not respect the personal freedoms of its people than those with lower levels of education. The difference is largest in Singapore, where 69% of those with a postsecondary degree or above say China does not respect the personal freedoms of its people compared with 51% of those with less schooling. Older people are more likely than younger ones to criticize China’s treatment of its people in seven nations surveyed. In Singapore and Taiwan, however, the pattern is reversed, wherein younger people are more critical of China.

In the U.S., China’s treatment of its own people is a highly salient issue. In an open-ended question asked only in the U.S. about what people think about when they think about China, one-in-five mentioned issues related to human rights, including 9% who specifically mentioned how the Chinese people lack freedoms like those of religion, speech and the right to assemble. To explore how Americans described China, see “Most Americans Have ‘Cold’ Views of China. Here’s What They Think About China, In Their Own Words.”

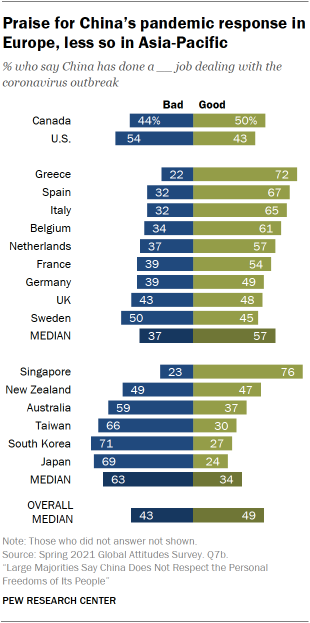

China’s COVID-19 response gains some approval but still pales compared with that of several other nations and institutions

After cases of the coronavirus began appearing in China’s Hubei Province in late 2019, publics gave China largely negative ratings for its handling of the pandemic. Now, more than a year since this initial outbreak and several months after China has itself largely reopened, the country garners much more positive, though still varying, reviews. A median of 49% across 17 publics say China has done a good job dealing with the coronavirus outbreak; 43% say it has done a bad job.

The most positive assessments of China’s pandemic response come from Europe, where a regional median of 57% believe China has done a good job. Roughly half or more in each European nation surveyed except Sweden share this viewpoint, though it is especially prevalent in Greece, Spain, Italy and Belgium.

In North America, opinions are more divided. Half of Canadians give China positive marks, while more than half of Americans (54%) hold the opposite view.

Among China’s neighbors in the Asia-Pacific, a regional median of 63% think China has done a bad job of handling the outbreak. A median of just 34% give a positive assessment. Roughly six-in-ten or more in South Korea, Japan, Taiwan and Australia hold negative opinions. New Zealanders offer more split assessments. The most positive views of China’s pandemic handling come from Singapore, where roughly three-quarters say China has done well with its management of COVID-19.

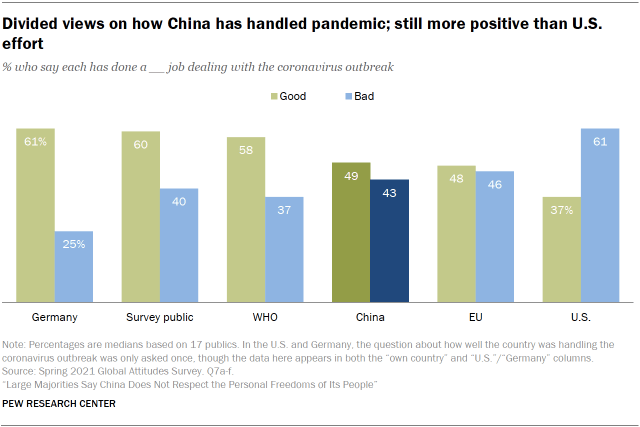

Compared with other countries and organizations, China is in the middle of the pack for its pandemic response. The highest marks for battling the coronavirus outbreak go to Germany, the respondent’s own locality and the World Health Organization (WHO), with a median of about six-in-ten who say each has done a good job. China performs about the same as the European Union, where a median of 48% think the EU has handled the pandemic well. China also fares much better than the U.S. – a median of just 37% positively evaluate the American response to the outbreak (though views of American handling of the pandemic have improved somewhat since 2020).

In seven countries – the U.S., Australia, the UK, Italy, Germany, New Zealand and Spain – those on the right of the political spectrum are more critical than those on the left of China’s pandemic handling. This ideological gap is widest in the U.S., where those on the right are 34 percentage points more likely than their left-leaning counterparts to say China has done a bad job dealing with the coronavirus.

Views of how China has handled the pandemic have become more positive since last summer. In the 12 countries surveyed both in the summer of 2020 and this spring for which trend data is available, the share saying China has done a good job dealing with the coronavirus outbreak has increased significantly, including double-digit increases in nine countries. In Belgium, for example, 40% in 2020 said China had done a good job handling the pandemic; now, 61% hold this opinion, a 21-point change.

Shares saying China has done a good job have increased in Australia, South Korea and Japan, but still fewer than four-in-ten consider China’s pandemic performance to be good.

(For more on changes in opinion related to how various countries and organizations have dealt with the pandemic, see the blog post “Global views of how U.S. has handled pandemic have improved, but few say it’s done a good job.”)

Most prefer close economic relationship with U.S. – not China

Around half or more in 15 of 16 publics surveyed would rather have close economic ties with the U.S. than with China. Those in Canada are the most likely to prefer ties with the U.S. over ties with China: Nearly nine-in-ten would make this choice.

Europeans surveyed also overwhelmingly consider strong economic ties with the U.S. more important than strong ties with China. More than three-quarters in Sweden hold this view, and about two-thirds or more in the Netherlands, UK and Italy agree. In France, about three-in-ten (29%) volunteer that ties to both countries are important as do roughly a fifth (23%) in Germany.

Views in the Asia-Pacific region vary more. Japanese and South Koreans are more than four times as likely to prefer economic ties with the U.S., and Australians and Taiwanese choose ties with the U.S. over ties with China by more than 20 percentage points. However, adults in New Zealand are about equally as likely to choose economic ties with either country. Further, for their part, Singaporeans stand apart from all other places surveyed for choosing a close economic relationship with China over a relationship with the U.S.

In the four countries where trend data is available, the share of adults who prioritize a strong economic relationship with the U.S. over China has grown. Compared with 2019, when the question was last asked, Australians are 16 percentage points more likely to value close economic ties with the U.S. The share expressing this opinion has increased by 11 points in Japan and 9 points in South Korea over the last two years. In Canada, where the question was last asked in 2015, the share has grown by 14 points.

National identity shapes how adults in Taiwan prioritize economic relationships. Those who see themselves as Taiwanese are more than 40 percentage points more likely than those who identify as both Taiwanese and Chinese to prioritize ties with the U.S. over ties with China. Similarly, in Singapore, ethnic identity plays a role. Singaporeans who identify as Chinese (57%) are much more likely than those who identify as Malay (35%) or Indian (22%) to prioritize ties with China.

Age is also related to which country people want to have strong economic ties to. While most would choose ties with the U.S., regardless of age, younger adults are more likely than older people to choose China in most publics. For example, a third of adults under 30 in Italy say they would prefer a strong economic relationship with China over one with the U.S., while 13% of adults 65 and older say the same – a difference of 20 percentage points. South Korean adults buck this trend, as those 65 and older are 14 points more likely than those 18 to 29 to say they prefer close economic ties to China.

Many lack faith in Xi’s handling of world affairs

Majorities in all but one of the 17 publics surveyed have little or no confidence in Chinese President Xi Jinping’s handling of world affairs. Roughly eight-in-ten in both North American countries lack confidence in the Chinese president. Among both Canadians and Americans, this is a significant increase from 2020.

At least seven-in-ten adults express no confidence in Xi in all but one European country surveyed. In France, Sweden and Germany, about half or more say they have no confidence at all in China’s president.

In the Asia-Pacific publics surveyed, majorities in all but Singapore say they have little to no confidence in Xi to deal with world affairs. With 86% expressing no confidence in the Chinese president, adults in Japan trust Xi the least in the region. At least two-thirds or more say the same in South Korea, Australia, New Zealand and Taiwan.

Confidence in Xi is related to views of China’s handling of COVID-19. Those who believe that China did at least a somewhat good job handling the outbreak are more likely to have confidence in Xi.

Age also factors into how adults view China’s president. In many places surveyed, older adults are more likely to say they have no confidence in Xi. In the UK, for example, 83% of adults 65 and older have no confidence in Xi, compared with 57% of those ages 18 to 29. Conversely, younger adults express more distrust in Xi in Taiwan (by 25 percentage points), South Korea (21 points) and Singapore (18 points).

No consensus on prioritizing human rights or building economic ties with China

Despite the widespread sense that China does not respect the personal freedoms of its people, publics are somewhat divided over what the appropriate response should be. People were asked to choose between two priorities: promoting human rights in China at the possible cost of harming economic relations with the country, or working on strengthening economic relations and leaving human rights issues unaddressed. When presented with these two options, more in the U.S. and Asia-Pacific region put promoting human rights over enhancing economic relations (this question was not asked in Europe or Canada). In the U.S., New Zealand and Australia, adults are more than twice as likely to prioritize human rights above economic ties.

In Japan and Taiwan, adults are also more likely to choose promoting human rights in China instead of prioritizing economic relations with China but by a slimmer margin (19 and 6 percentage points, respectively). Significant minorities in both places did not provide a response.

Singaporeans and South Koreans are more likely to choose prioritizing strengthening economic relations with China, even if it means not addressing human rights issues. The margin is greatest in South Korea, where a majority of 57% choose prioritizing economic relations, compared with 39% who choose promoting human rights in China.

Across nearly all Asian-Pacific publics surveyed, those who choose strong economic ties with China over ties with the U.S. are also more likely to choose economic ties with China over promoting human rights in the country. The difference is greatest in Taiwan (36 percentage points); double-digit differences also appear in Japan, Singapore, South Korea and Australia. Only in New Zealand are adults nearly equally likely to prioritize promoting human rights and strengthening economic ties, regardless of the country with whom they want closer economic ties.

In Singapore, views on what the country should prioritize in its relationship with China differ by ethnic identity. A majority of Singaporean adults who say their ethnicity is Chinese place strengthening economic ties over promoting human rights (59%), while fewer than half of those who say their ethnicity is Malay or Indian say the same (45% and 45%, respectively). Likewise, a majority in Taiwan who say they are both Taiwanese and Chinese (57%) compared with roughly three-in-ten of those labelling themselves Taiwanese (31%) hold this opinion.