Many doubt success of international efforts to reduce global warming

This analysis focuses on attitudes toward global climate change around the world. For this report, we conducted nationally representative Pew Research Center surveys of 16,254 adults from March 12 to May 26, 2021, in 16 advanced economies. All surveys were conducted over the phone with adults in Canada, Belgium, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, the UK, Australia, Japan, New Zealand, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan.

In the United States, we surveyed 2,596 U.S. adults from Feb. 1 to 7, 2021. Everyone who took part in the U.S. survey is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories.

This study was conducted in countries where nationally representative telephone surveys are feasible. Due to the coronavirus outbreak, face-to-face interviewing is not currently possible in many parts of the world.

Here are the questions used for the report, along with responses. See our methodology database for more information about the survey methods outside the U.S. For respondents in the U.S., read more about the ATP’s methodology.

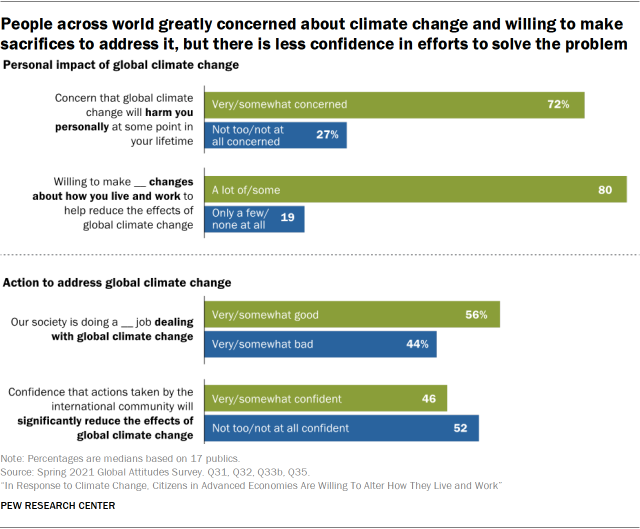

A new Pew Research Center survey in 17 advanced economies spanning North America, Europe and the Asia-Pacific region finds widespread concern about the personal impact of global climate change. Most citizens say they are willing to change how they live and work at least some to combat the effects of global warming, but whether their efforts will make an impact is unclear.

Citizens offer mixed reviews of how their societies have responded to climate change, and many question the efficacy of international efforts to stave off a global environmental crisis.

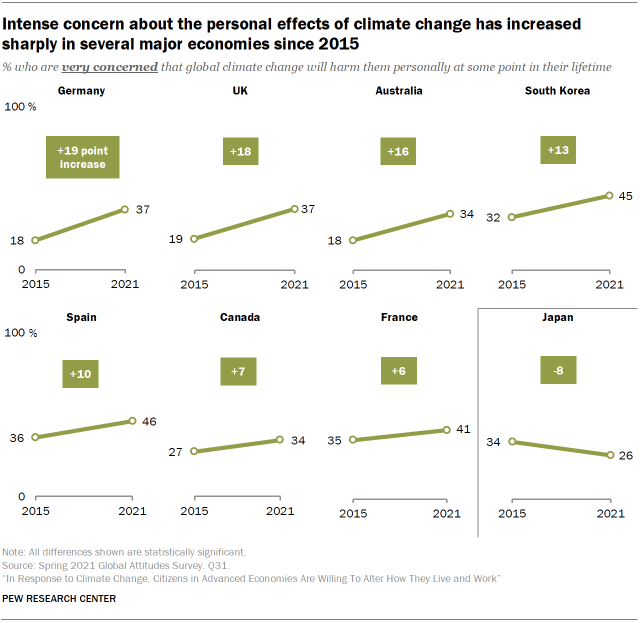

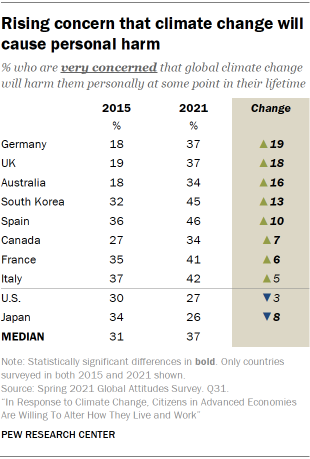

Conducted this past spring, before the summer season ushered in new wildfires, droughts, floods and stronger-than-usual storms, the study reveals a growing sense of personal threat from climate change among many of the publics polled. In Germany, for instance, the share that is “very concerned” about the personal ramifications of global warming has increased 19 percentage points since 2015 (from 18% to 37%).

In the study, only Japan (-8 points) saw a significant decline in the share of citizens deeply concerned about climate change. In the United States, views did not change significantly since 2015.

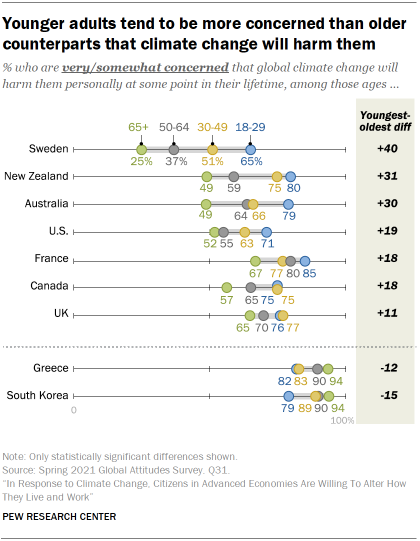

Young adults, who have been at the forefront of some of the most prominent climate change protests in recent years, are more concerned than their older counterparts about the personal impact of a warming planet in many publics surveyed. The widest age gap is found in Sweden, where 65% of 18- to 29-year-olds are at least somewhat concerned about the personal impacts of climate change in their lifetime, compared with just 25% of those 65 and older. Sizable age differences are also found in New Zealand, Australia, the U.S., France and Canada.

Public concern about climate change appears alongside a willingness to reduce its effects by taking personal steps. Majorities in each of the advanced economies surveyed say they are willing to make at least some changes in how they live and work to address the threat posed by global warming. And across all 17 publics polled, a median of 34% are willing to consider “a lot of changes” to daily life as a response to climate change.

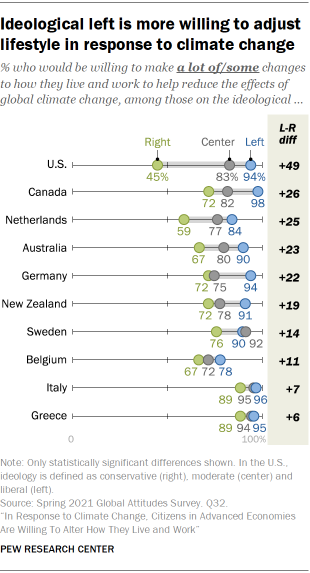

Generally, those on the left of the political spectrum are more open than those on the right to taking personal steps to help reduce the effects of climate change. This is particularly true in the U.S., where citizens who identify with the ideological left are more than twice as willing as those on the ideological right (94% vs. 45%) to modify how they live and work for this reason. Other countries where those on the left and right are divided over whether to alter their lives and work in response to global warming include Canada, the Netherlands, Australia and Germany.

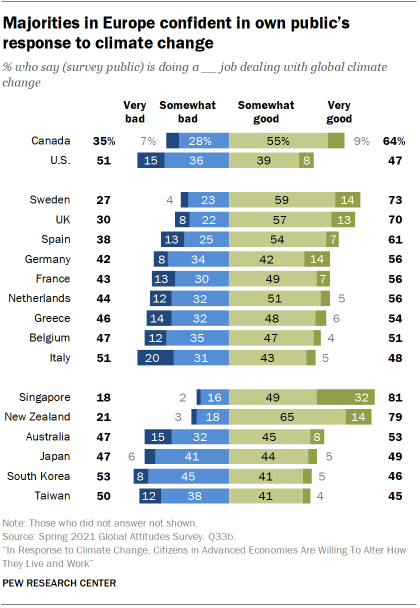

Beyond individual actions, the study reveals mixed views on the broader, collective response to climate change. In 12 of the 17 publics polled, half or more think their own society has done a good job dealing with global climate change. But only in Singapore (32%), Sweden (14%), Germany (14%), New Zealand (14%) and the United Kingdom (13%) do more than one-in-ten describe such efforts as “very good.” Meanwhile, fewer than half in Japan (49%), Italy (48%), the U.S. (47%), South Korea (46%) and Taiwan (45%) give their society’s climate response favorable marks.

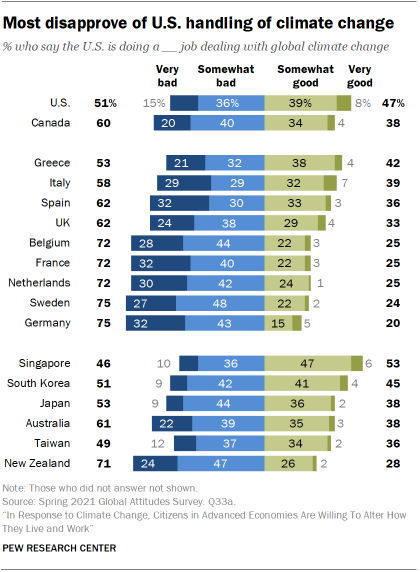

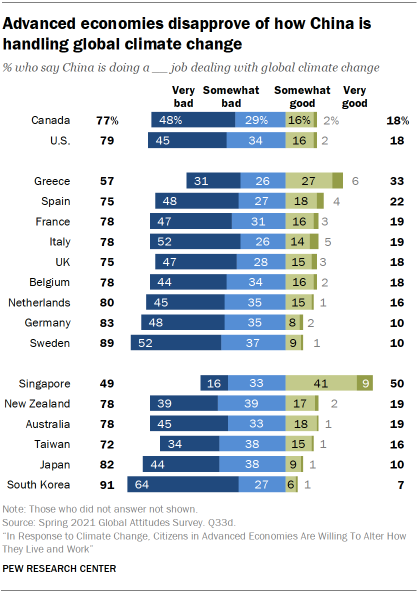

Abroad, the U.S. response to climate change is generally seen as wanting. Among the 16 other advanced economies surveyed, only Singaporeans are slightly positive in their assessment of American efforts (53% say the U.S. is doing a “good job” of addressing climate change). Elsewhere judgments are harsher, with six-in-ten or more across Australia, New Zealand and many of the European publics polled saying the U.S. is doing a “bad job” of dealing with global warming. However, China fares substantially worse in terms of international public opinion: A median of 78% across 17 publics describe China’s handling of climate change as “bad,” including 45% who describe the Chinese response as “very bad.” That compares with a cumulative median of 61% who judge the American response as “bad.”

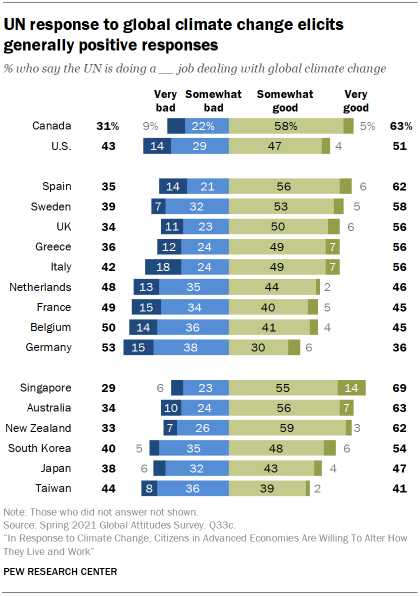

At the cross-national level, the European Union’s response to climate change is viewed favorably by majorities in each of the advanced economies surveyed, except Germany where opinion is split (49% good job; 47% bad job). However, there is still room for improvement, as only a median of 7% across the publics polled describe the EU’s efforts as “very good.” The United Nations’ actions to address global warming are also generally seen in a favorable light: A median of 56% say the multilateral organization is doing a good job. But again, the reviews are tempered, with just 5% describing the UN’s response to climate change as “very good.”

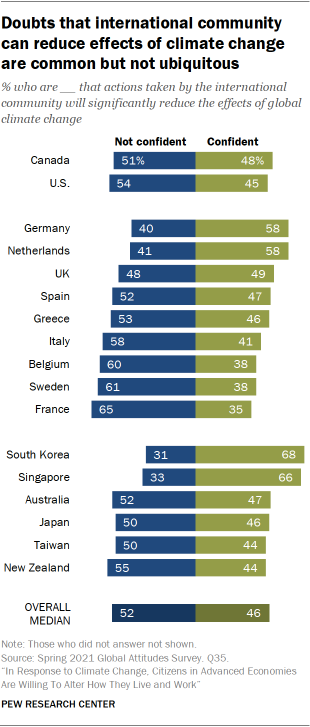

Publics in the advanced economies surveyed are divided as to whether actions by the international community can successfully reduce the effects of global warming. Overall, a median of 52% lack confidence that a multilateral response will succeed, compared with 46% who remain optimistic that nations can respond to the impact of climate change by working together. Skepticism of multilateral efforts is most pronounced in France (65%), Sweden (61%) and Belgium (60%), while optimism is most robust in South Korea (68%) and Singapore (66%).

These are among the findings of a new Pew Research Center survey, conducted from Feb. 1 to May 26, 2021, among 18,850 adults in 17 advanced economies.

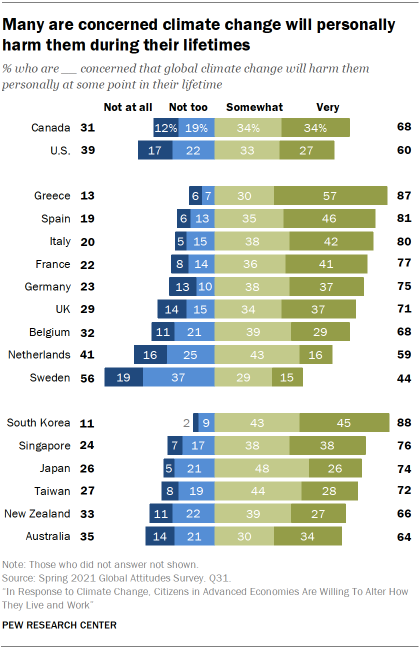

People concerned climate change will harm them during their lifetimes

Many people across 17 advanced economies are concerned that global climate change will harm them personally at some point in their lifetime. A median of 72% express at least some concern that they will be personally harmed by climate change in their lifetimes, compared with medians of 19% and 11% who say they are not too or not at all concerned, respectively. The share who say they are very concerned climate change will harm them personally ranges from 15% in Sweden to 57% in Greece.

Roughly two-thirds of Canadians and six-in-ten Americans are worried climate change will harm them in their lifetimes. Only 12% of Canadians and 17% of Americans are not at all concerned about the personal impact of global climate change.

Publics in Europe express various degrees of concern for potential harm caused by climate change. Three-quarters or more of those in Greece, Spain, Italy, France and Germany say they are concerned that climate change will harm them at some point during their lives. Only in Sweden does less than a majority of adults express concern about climate change harming them. Indeed, 56% of Swedes are not concerned about personal harm related to climate change.

In general, Asia-Pacific publics express more worry about climate change causing them personal harm than not. The shares who express concern range from 64% in Australia to 88% in South Korea. About one-third or more in South Korea, Singapore and Australia say they are very concerned climate change will harm them personally.

The share who are very concerned climate change will harm them personally at some point during their lives has increased significantly since 2015 in nearly every country where trend data is available. In Germany, for example, the share who say they are very concerned has increased 19 percentage points over the past six years. Double-digit changes are also present in the UK (+18 points), Australia (+16), South Korea (+13) and Spain (+10). The only public where concern for the harm from climate change has decreased significantly since 2015 is Japan (-8 points).

While many worry climate change will harm them personally in the future, there is widespread sentiment that climate change is already affecting the world around them. In Pew Research Center surveys conducted in 2019 and 2020, a median of 70% across 20 publics surveyed said climate change is affecting where they live a great deal or some amount. And majorities in most countries included as part of a 26-nation survey in 2018 thought global climate change was a major threat to their own country (the same was true across all 14 countries surveyed in 2020).

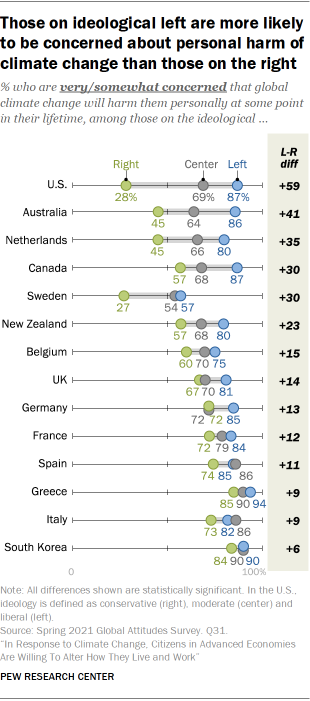

Those who place themselves on the left of the ideological spectrum are more likely than those who place themselves on the right to be concerned global climate change will harm them personally during their lifetime. This pattern is present across all 14 nations where ideology is measured. In 10 of these 14, though, majorities across the ideological left, center and right are concerned climate change will harm them personally.

The difference is starkest in the U.S.: Liberals are 59 percentage points more likely than conservatives to express concern for this possibility (87% vs. 28%, respectively). However, large ideological differences are also present in Australia (with liberals 41 points more likely to say this), the Netherlands (+35), Canada (+30), Sweden (+30) and New Zealand (+23).

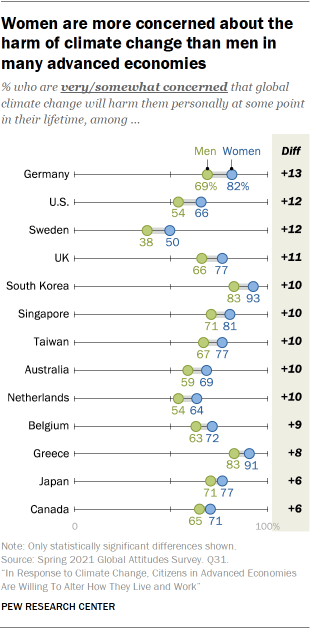

Women are more concerned than men that climate change will harm them personally in many of the publics polled. In Germany, women are 13 points more likely than men to be concerned that climate change will cause them harm (82% vs 69%, respectively). Double-digit differences are also present across several publics, including the U.S., Sweden, the UK, South Korea, Singapore, Taiwan, Australia and the Netherlands.

When this question was first asked in 2015, women were also more likely to express concern than their male counterparts that climate change will harm them in the U.S., Germany, Canada, Japan, Spain and Australia.

Young people have been at the forefront of past protests seeking government action on climate change. In eight places surveyed, young adults ages 18 to 29 are more likely than those 65 and older to be concerned climate change will harm them during their lifetime. The difference is greatest in Sweden, home of youth climate activist Greta Thunberg. Young Swedes are 40 points more likely than their older counterparts to say they are concerned about harm from climate change. Large age gaps are also present in New Zealand (with younger adults 31 points more likely to say this), Australia (+30) and Singapore (+20). And young Americans, French, Canadians and Brits are also more likely to say that climate change will personally harm them in their lifetimes.

While large majorities across every age group in Greece and South Korea are concerned climate change will harm them personally, those ages 65 and older are more likely to hold this sentiment than those younger than 30.

Many across the world willing to change how they live and work to reduce effects of climate change

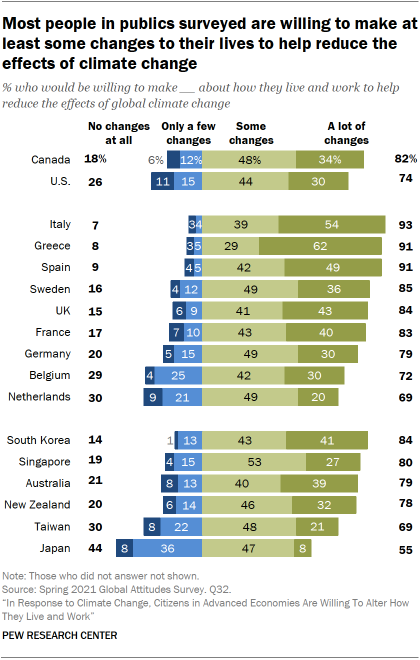

Many across the publics surveyed say they are willing to make at least some changes to the way they live and work to reduce the effects of climate change. A median of 80% across 17 publics say they would make at least some changes to their lives to reduce the effects of climate change, compared with a median of 19% who say they would make a few changes or no changes at all. The share willing to make a lot of changes ranges from 8% in Japan to 62% in Greece.

In North America, about three-quarters or more of both Canadians and Americans say they are willing to make changes to reduce the effects of climate change.

Large majorities across each of the European publics surveyed say they are willing to change personal behavior to address climate change, but the share who say they are willing to make a lot of changes varies considerably. About half or more in Greece, Italy and Spain say they would make a lot of changes, while fewer than a third in Belgium, Germany and the Netherlands say the same.

Majorities in each of the Asia-Pacific publics polled say they would make some or a lot of changes to how they live and work to combat the effects of climate change, including more than three-quarters in South Korea, Singapore, Australia and New Zealand. But in Japan, fully 44% say they are willing to make few or no changes to how they live and work to address climate change, the largest share of any public surveyed.

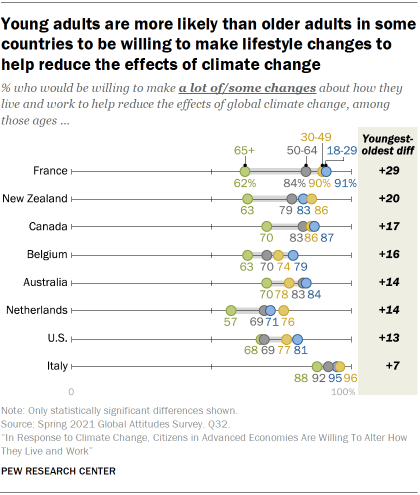

In eight countries surveyed, those ages 18 to 29 are more likely than those 65 and older to say they are willing to make at least some changes to how they live and work to help reduce the effects of climate change. In France, for example, about nine-in-ten of those younger than 30 are willing to make changes in response to climate change, compared with 62% of those 65 and older.

Ideologically, those on the left are more likely than those on the right to express willingness to change their behavior to help reduce the effects of global climate change. The ideological divide is widest in the U.S., where 94% of liberals say they are willing to make at least some changes to how they live and work to help reduce the effects of climate change, compared with 45% of conservatives. Large ideological differences are also present between those on the left and the right in Canada (a difference of 26 percentage points), the Netherlands (25 points), Australia (23 points) and Germany (22 points).

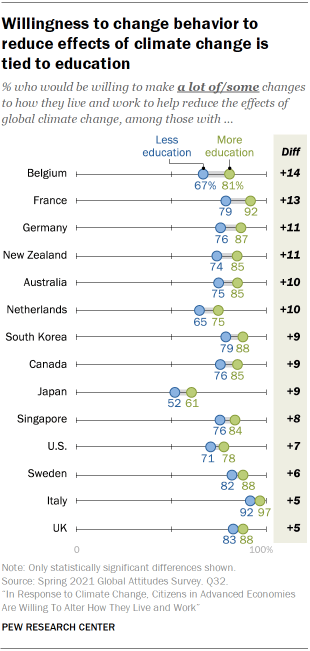

In most publics, those with more education are more likely than those with less education to say they are willing to adjust their lifestyles in response to the impact of climate change.1 In Belgium, for example, those with a postsecondary degree or higher are 14 points more likely than those with a secondary education or below to say they are willing to make changes to the way they live. Double-digit differences are also present between those with more education and less education in France, Germany, New Zealand, the Netherlands and Australia.

And in most places surveyed, those with a higher-than-median income are more likely than those with a lower income to express willingness to make at least some changes to reduce the effects of climate change. For example, in Belgium, about three-quarters (76%) of those with a higher income say they would make changes to their lives, compared with 66% of those with a lower income.

Many are generally positive about how their society is handling climate change

Respondents give mostly positive responses when asked to reflect on how their own society is handling climate change. Around half or more in most places say they their society is doing at least a somewhat good job, with a median of 56% saying this across the 17 advanced economies.

Roughly two-thirds (64%) of Canadians say their country is doing a good job, while nearly half of Americans say the same.

In most of the European publics surveyed, majorities believe their nation’s climate change response is at least somewhat good. Those in Sweden and the UK are especially optimistic, with around seven-in-ten saying their society is doing a good job dealing with climate change. In Europe, Italians are the most critical of their country’s performance: 20% say their society is doing a very bad job, the largest share among all publics surveyed.

Around eight-in-ten in Singapore and New Zealand say their publics are doing a good job – the highest levels among all societies surveyed. This includes around a third (32%) in Singapore who say they are doing a very good job. Adults in the other Asia-Pacific publics surveyed are more circumspect; about half or fewer say their society is doing a good job.

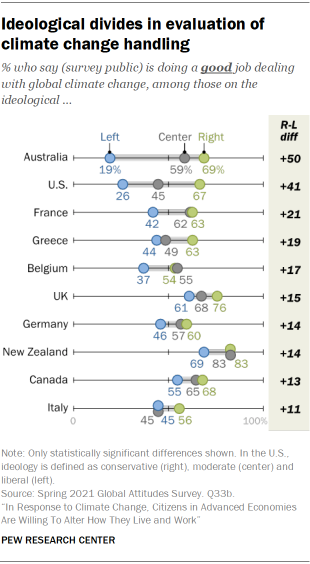

Political ideology plays a role in how people evaluate their own public’s handling of climate change. For adults in 10 countries, those on the right tend to rate their country’s performance with regard to climate change more positively. The difference is most stark in Australia: 69% of those on the right say Australia is handling climate change well, compared with just 19% of those on the left – a 50-point difference. A striking difference also appears in the U.S., where conservatives are 41 points more likely than liberals to say the U.S. is doing a good job dealing with climate change.

Evaluations are also tied to how people view governing parties. In 10 of 17 publics surveyed, people who see the governing party positively are more likely than those with a negative view of the party to think climate change is being handled well. The opposite is true in the U.S., where only 33% of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents say the U.S. is handling climate change well, compared with 61% of those who do not support the Democratic Party.

Mixed views on whether action by the international community can reduce the effects of climate change

Only a median of 46% across the publics polled are confident that actions taken by the international community will significantly reduce the effects of climate change. A median of 52% are not confident these actions will reduce the effects of climate change.

Canadians are generally divided on whether international climate action can reduce the impact of climate change. And 54% of Americans are not confident in the international community’s response to the climate crisis.

In Europe, majorities in Germany and the Netherlands express confidence that international climate action can significantly address climate change. However, majorities in France, Sweden, Belgium and Italy are not confident in climate actions taken by the international community.

South Koreans and Singaporeans say they are confident in international climate action, but elsewhere in the Asia-Pacific region, public opinion is either divided or leans toward pessimism about international efforts.

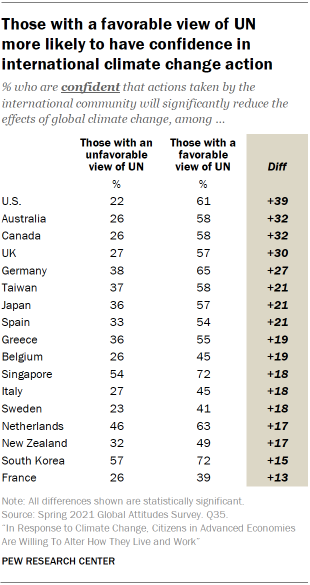

Opinion of international organizations, like the United Nations, is linked to confidence that actions taken by the international community will significantly reduce the effects of global climate change. Those with a favorable view of the UN are more confident that actions taken by the international community will significantly reduce the effects of climate change than those with an unfavorable view of the UN. This difference is largest in the U.S., where 61% with a favorable view of the UN say international action will reduce the effects of climate change, compared with just 22% of those with an unfavorable view of the organization. Double-digit differences are present in every public polled.

Similarly, in every EU member state included in the survey, those with favorable views of the bloc are more likely to have confidence in international efforts to combat climate change than those with unfavorable views.

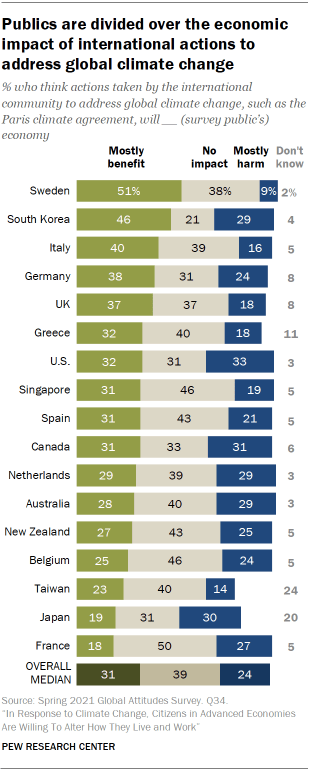

Little consensus on whether international climate action will harm or benefit domestic economies

Relatively few in the advanced economies surveyed think actions taken by the international community to address climate change, such as the Paris climate agreement, will mostly benefit or harm their own economy. A median of 31% across 17 publics say these actions will be good for their economy, while a median of 24% believe such actions will mostly harm their economy. A median of 39% say actions like the Paris climate agreement will have no economic impact.

In Sweden, about half (51%) feel international climate actions will mostly benefit their economy. On the other hand, only 18% in France say their public will benefit economically from international climate agreements.

In no public do more than a third say international action on climate change will harm their economy. But in the U.S., which pulled out of the Paris climate agreement under former President Donald Trump and has just recently rejoined the accord under President Joe Biden, a third say international climate agreements will harm the economy. (For more on how international publics view Biden’s international policy actions, see “America’s Image Abroad Rebounds With Transition From Trump to Biden.”)

The more widespread sentiment among those surveyed is that climate actions will have no impact on domestic economies. In eight publics, four-in-ten or more hold this opinion, including half in France. And in two places – Japan and Taiwan – one-in-five or more offer no opinion.

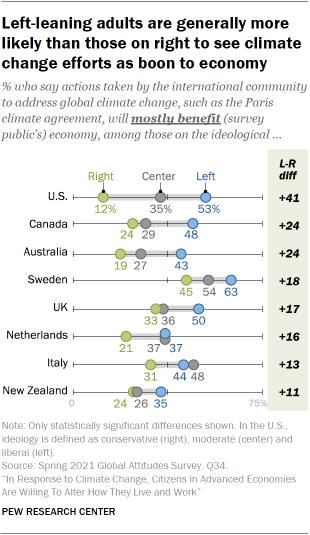

Those on the left of the ideological spectrum are more likely than those on the right to say international action to address climate change – such as the Paris Agreement – will mostly benefit their economies. U.S. respondents are particularly divided by ideology. Roughly half (53%) of liberals feel international actions related to climate change will benefit the U.S. economy, compared with just 12% of conservatives. The next largest difference is in Canada, where those on the left are 24 percentage points more likely than those on the right to think this type of international action will benefit their economy.

Those on the right in many publics are, in turn, more likely than those on the left to think international actions such as the Paris Agreement will mostly harm their economies. Here again, ideological divisions in the U.S. are much larger than those in other publics: 65% of conservatives say international climate change actions will harm the American economy, compared with 12% of liberals who say the same.

In several advanced economies, those who say their current economic situation is good are more likely to say that actions taken by the international community to address climate change will mostly benefit their economies than those who say the economic situation is bad. In Sweden, for example, a majority (55%) of those who say the current economic situation is good also believe international action like the Paris Agreement will benefit the Swedish economy, compared with 31% who are more negative about the state of the economy.

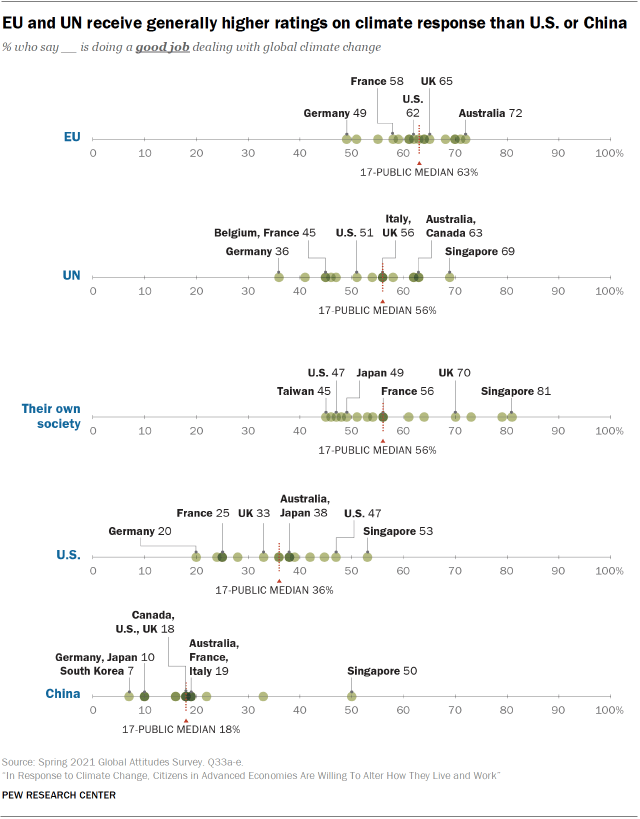

Evaluating the climate change response from the EU, UN, U.S. and China

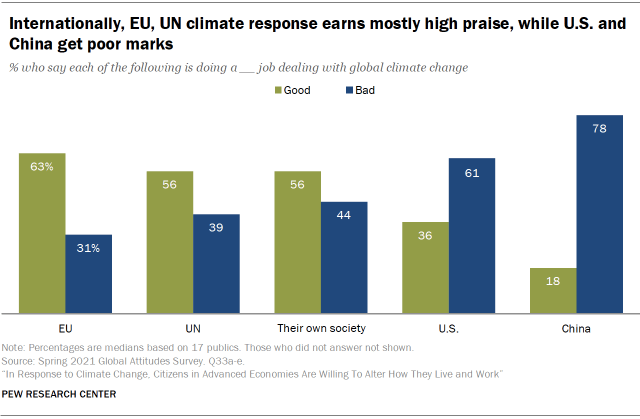

In addition to reflecting on their own public, respondents were asked to evaluate how four international organizations or countries are handling global climate change. Of the entities asked about, the European Union receives the best ratings, with a median of 63% across the 17 publics surveyed saying the EU is doing a good job handling climate change. A median of 56% say the same for the United Nations. Far fewer believe the U.S. or China – the two leading nations in carbon dioxide emissions – are doing a good job.

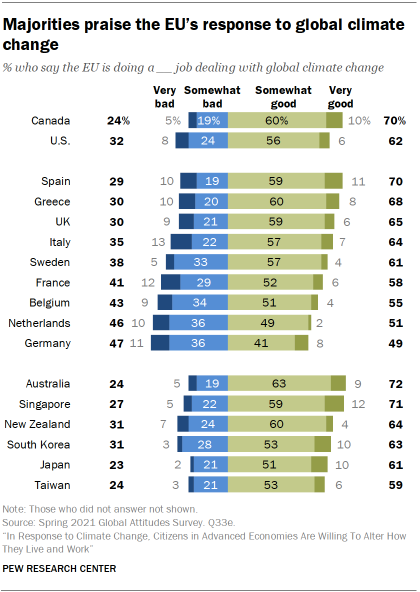

EU handling of climate change receives high marks in and outside of Europe

Majorities in all but two of the publics surveyed think the EU is doing a good job addressing climate change. However, this positivity is tempered, with most respondents saying the EU’s effort is somewhat good, but few saying it is very good.

Praise for the bloc’s response to climate change is common among the European countries surveyed. In Spain and Greece, around seven-in-ten say the EU is doing at least a somewhat good job, and about six-in-ten or more in the UK, Italy, Sweden and France agree. The Dutch and Germans have more mixed feelings about how the EU is responding to climate change. Notably, only about one-in-ten say the EU is doing a very bad job handling climate change in every European country surveyed but Sweden, where only 5% say so.

Seven-in-ten Canadians believe the EU is doing a good job dealing with climate change, and 62% in the U.S. express the same view.

The Asia-Pacific publics surveyed report similarly positive attitudes on the EU’s climate plans. Around seven-in-ten Australians and Singaporeans consider the EU’s response to climate change at least somewhat good. About six-in-ten or more in New Zealand, South Korea, Japan and Taiwan echo this sentiment.

Climate change actions by UN seen positively among most surveyed

Majorities in most publics also consider the UN response to climate change to be good. A median of 49% across all publics surveyed say that the UN’s actions are somewhat good, and a median of 5% say the actions are very good.

Canadians evaluate the UN’s performance on climate more positively than Americans do. In Canada, roughly six-in-ten say the multilateral organization is doing at least a somewhat good job handling climate change. About half of those in the U.S. agree with that evaluation, with 43% of Americans saying the UN is doing a bad job of dealing with climate change.

In Europe, majorities in Spain, Sweden, the UK, Greece and Italy approve of how the UN is dealing with climate change. Fewer than half of adults in the Netherlands, France and Belgium agree with this evaluation, and only about a third in Germany say the same.

Singaporeans stand out as the greatest share of adults among those surveyed who see the UN’s handling of climate change as good. This includes 14% who say the UN response is very good, which is at least double the share in all other societies surveyed. Majorities in Australia and New Zealand similarly say that the UN is doing a good job.

Many critical of U.S. approach to climate change

In most publics surveyed, adults who say the U.S. is doing a good job of handling climate change are in the minority. A median of 33% say the U.S. is doing a somewhat good job, and a median of just 3% believe the U.S. is doing a very good job.

About half of Americans say their own country is doing a good job in dealing with global climate change, but six-in-ten Canadians say their southern neighbor is doing a bad job.

Across Europe, most think the U.S. is doing a bad job of addressing climate change, including 75% of Germans and Swedes. And at least a quarter in all European nations surveyed except the UK and Greece say the U.S. is doing a very bad job.

Singaporeans offer the U.S. approach to climate change the most praise in the Asia-Pacific region and across all publics surveyed; around half say they see the U.S. strategy positively. New Zealanders are the most critical in the Asia-Pacific region: Only about a quarter say the U.S. is doing at least a somewhat good job.

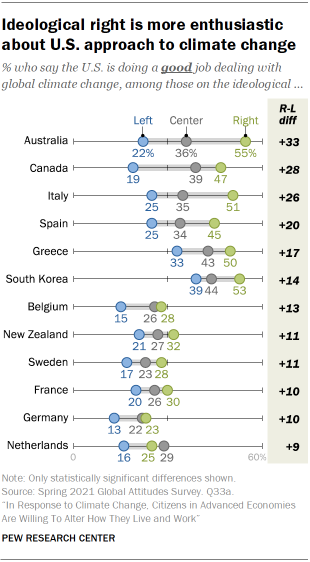

Political ideology is linked to evaluations of the U.S. climate strategy. In 12 countries, those on the right of the political spectrum are significantly more likely than those on the left to say the U.S. is doing a good job dealing with global climate change. The difference is greatest in Australia, Canada and Italy.

Few give China positive marks for handling of climate change

The publics surveyed are unenthusiastic about how China is dealing with climate change. A median of 18% across the publics say China is doing a good job, compared with a median of 78% who say the opposite. Notably, a median of 45% say that China is doing a very bad job handling climate change.

Just 18% of Americans and Canadians believe China is doing a good job handling climate change.

Similarly, few in Europe think China is dealing effectively with climate change. In fact, more than four-in-ten in nearly all European countries polled say China is doing a very bad job with regards to climate change. Criticism is less common in Greece, where a third give China positive marks for its climate change action.

Adults in the Asia-Pacific region also generally give China poor ratings for dealing with climate change. South Koreans are exceptionally critical; about two-thirds say China is doing a very bad job, the highest share in all publics surveyed. About four-in-ten or more in New Zealand, Japan and Australia concur. Singaporeans stand out, as half say China is doing a good job, nearly 20 percentage points higher than the next highest public.

In nine countries surveyed, those with less education are more positive toward China’s response to climate change than those with more education. Likewise, those with lower incomes are more inclined to provide positive evaluations of China’s climate change response. Those with less education or lower incomes are also less likely to provide a response in several publics.

CORRECTION (Oct. 13, 2021): In the chart “Publics are divided over the economic impact of international actions to address global climate change,” the “Don’t Know” column has been edited to reflect updated percentages to correct for a data tabulation error. These changes did not affect the report’s substantive findings.