People see UN favorably and believe ‘common values’ are more important for bringing nations together than ‘common problems’

This Pew Research Center analysis focuses on public opinion of global threats and international cooperation in 19 advanced economies in North America, Europe, Israel and the Asia-Pacific region. Global threats and views of international cooperation are examined in the context of long-term trend data and demographic analyses.

For non-U.S. data, this report draws on nationally representative surveys of 20,944 adults from Feb. 14 to June 3, 2022. All surveys were conducted over the phone with adults in Canada, Belgium, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, the United Kingdom, Japan, Malaysia, Singapore and South Korea. Surveys were conducted face to face in Hungary, Poland and Israel. The survey in Australia was conducted online. For more, see the Australia methodology.

In the United States, we surveyed 3,581 U.S. adults from March 21 to 27, 2022. Everyone who took part in this survey is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology. Here are the questions used for the report, along with responses, and the survey methodology.

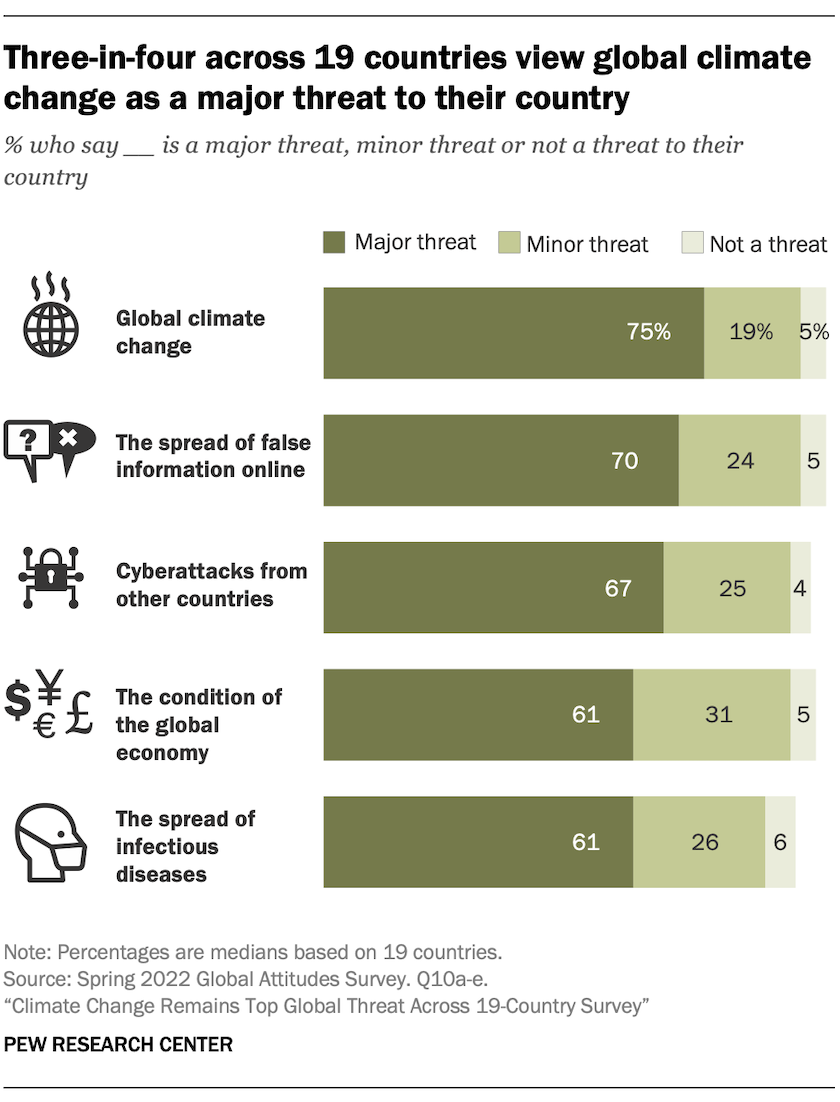

With the COVID-19 pandemic still raging, a hot war between Russia and Ukraine ongoing, inflation rates rising globally and heat records being smashed across parts of the world, countries are facing a wide variety of challenges in 2022. Among the many threats facing the globe, climate change stands out as an especially strong concern among citizens in advanced economies, according to a new Pew Research Center survey. A median of 75% across 19 countries in North America, Europe and the Asia-Pacific region label global climate change as a major threat.

This is not to say people are unconcerned about the other issues tested. Majorities in most countries view the spread of false information online, cyberattacks from other countries, the condition of the global economy and the spread of infectious diseases (like COVID-19) as major threats to their nations.

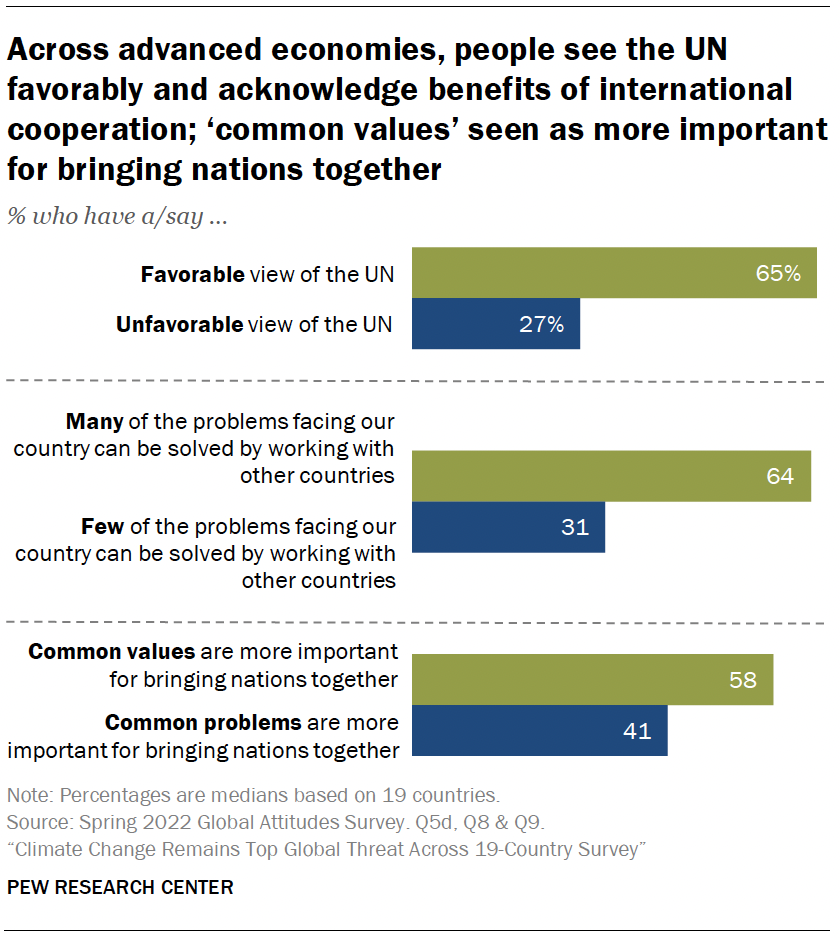

And despite the many depressing stories dominating the international news cycle, there is also a note of positivity among survey respondents in views of the United Nations, the benefits of international cooperation for solving problems and the importance of common values for bringing nations together.

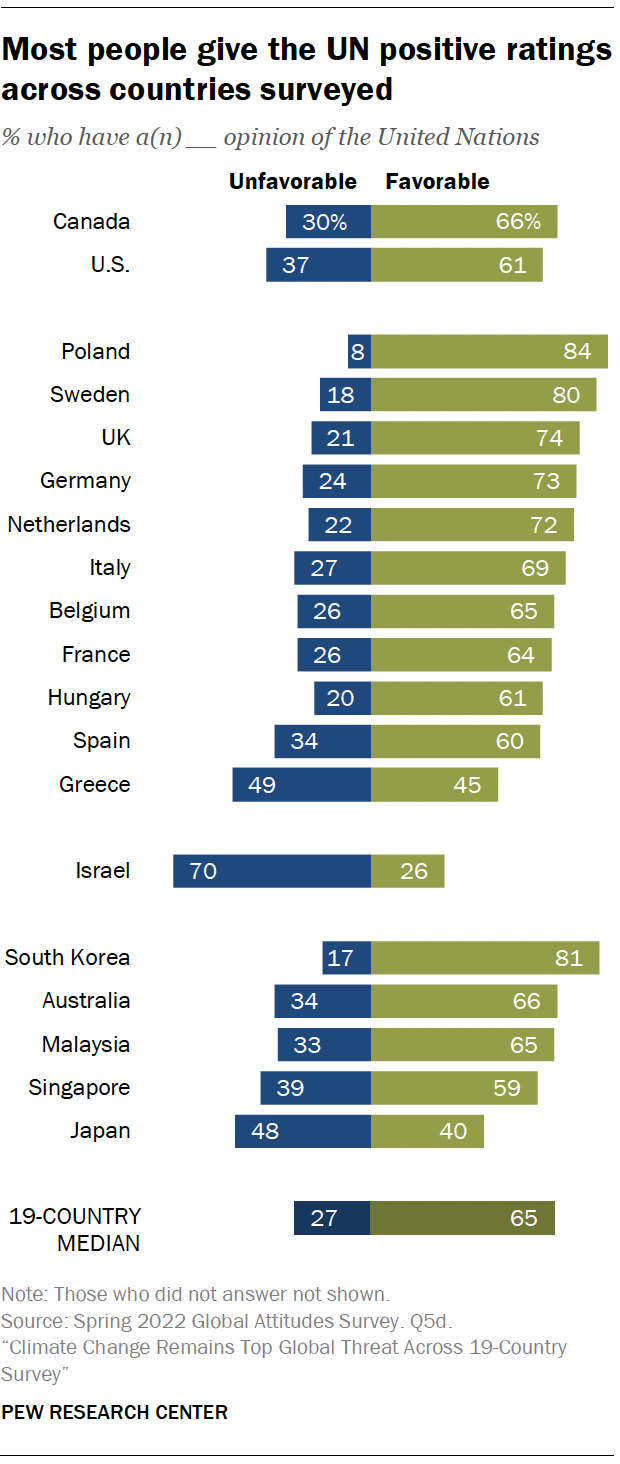

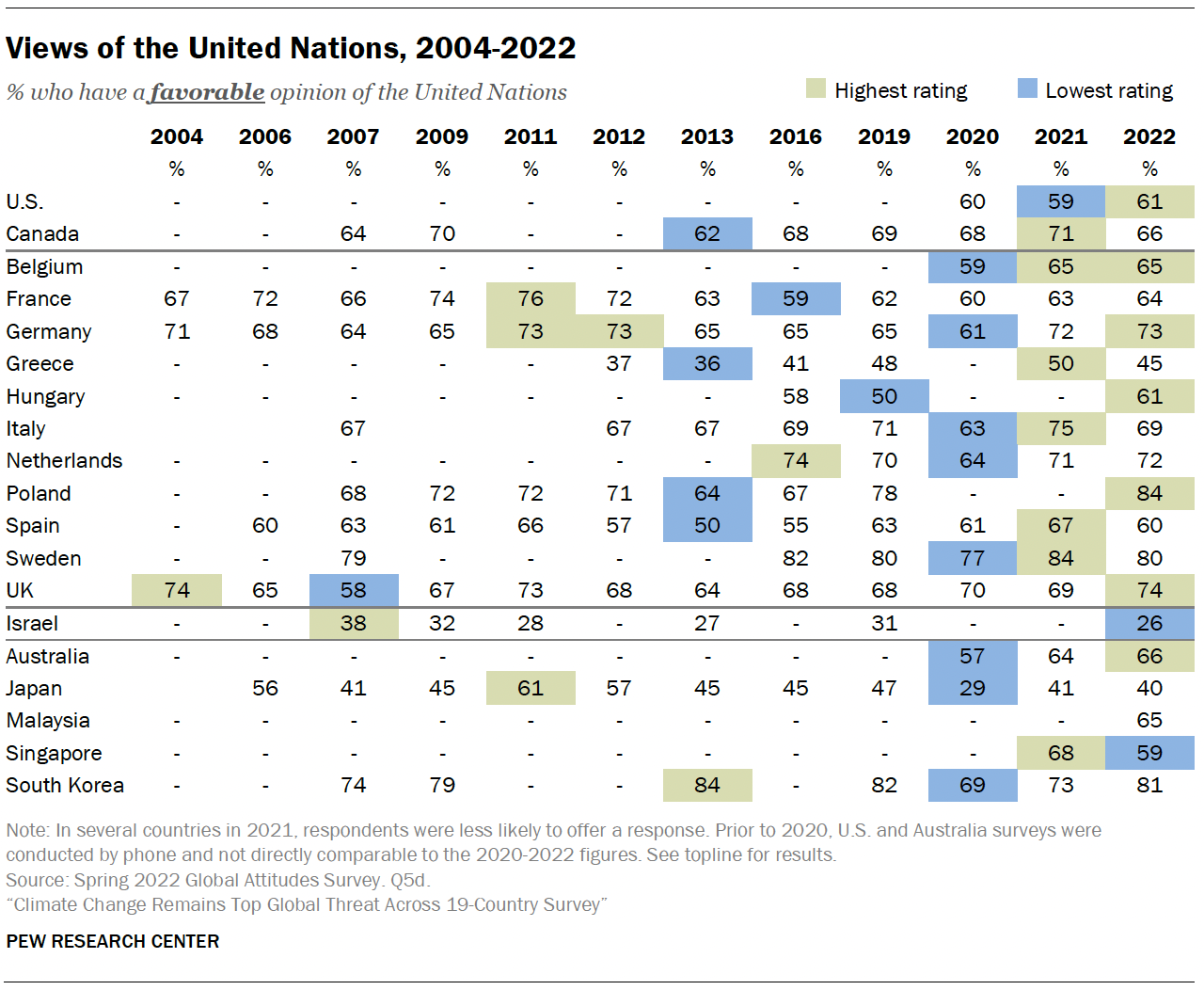

In the current survey, a median of 65% have a favorable view of the UN and only 27% have an unfavorable view of the international organization. Views of the UN have remained generally positive since the question was first asked in 2004.

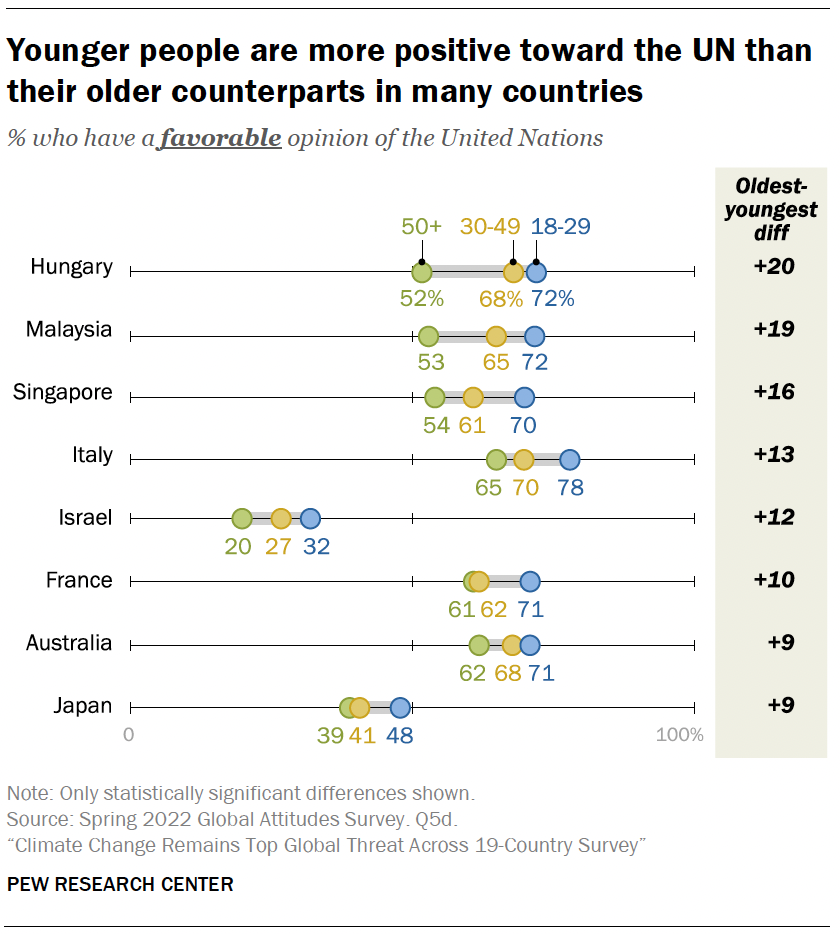

Among the countries surveyed, views of the UN are most positive in Poland, South Korea and Sweden. But among Israelis, seven-in-ten have an unfavorable opinion of the international body and about half of Greeks and Japanese say the same. In some countries, support for the UN is also strongest among young adults (ages 18 to 29) and those on the ideological left. This is especially true in the United States, where liberals are twice as likely as conservatives to have a positive view of the UN.

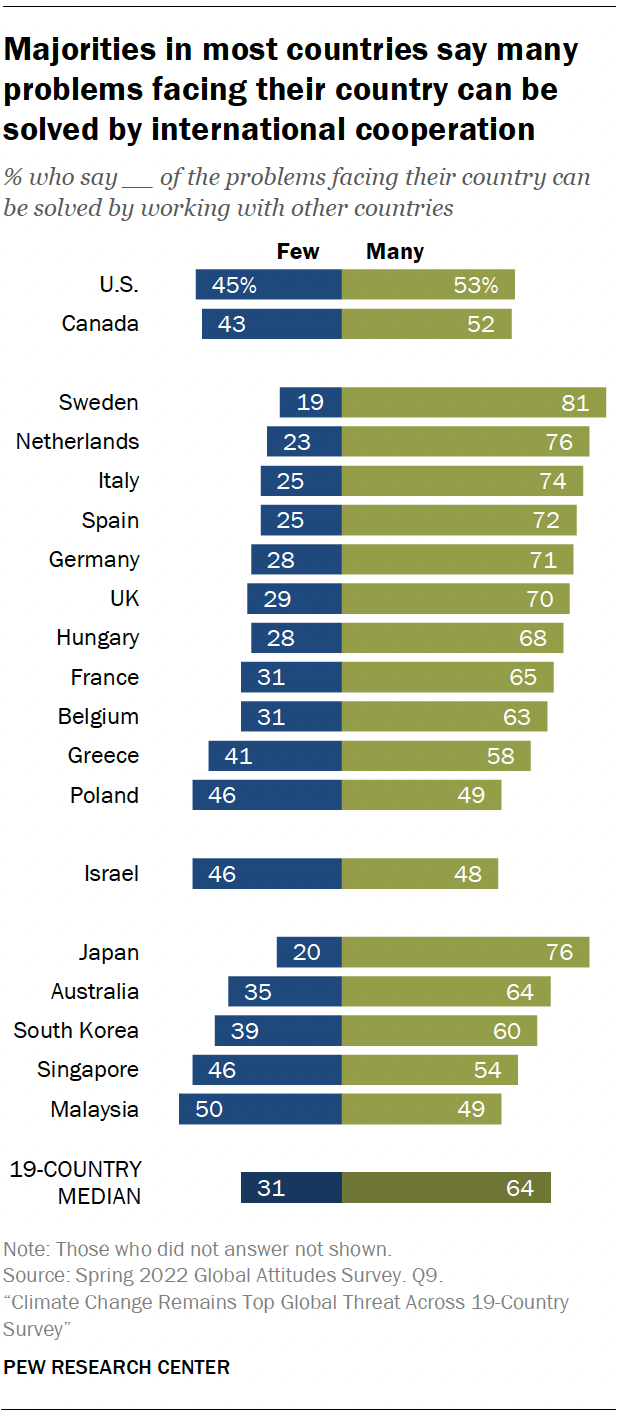

People around the world also express an optimism that the problems facing their country can be solved by working with other countries. A median of 64% say many problems can be solved by working together, while only 31% say that few problems can be solved by way of international cooperation.

The most optimistic sentiment on international cooperation in the current survey comes from Sweden, where 81% say that many of the problems facing the country can be solved by working with other countries. Across the 11 European countries, a median of 70% share this view. And in most of the countries surveyed, those who say many of the problems facing their country can be fixed by working with other countries are also more positively inclined toward the UN.

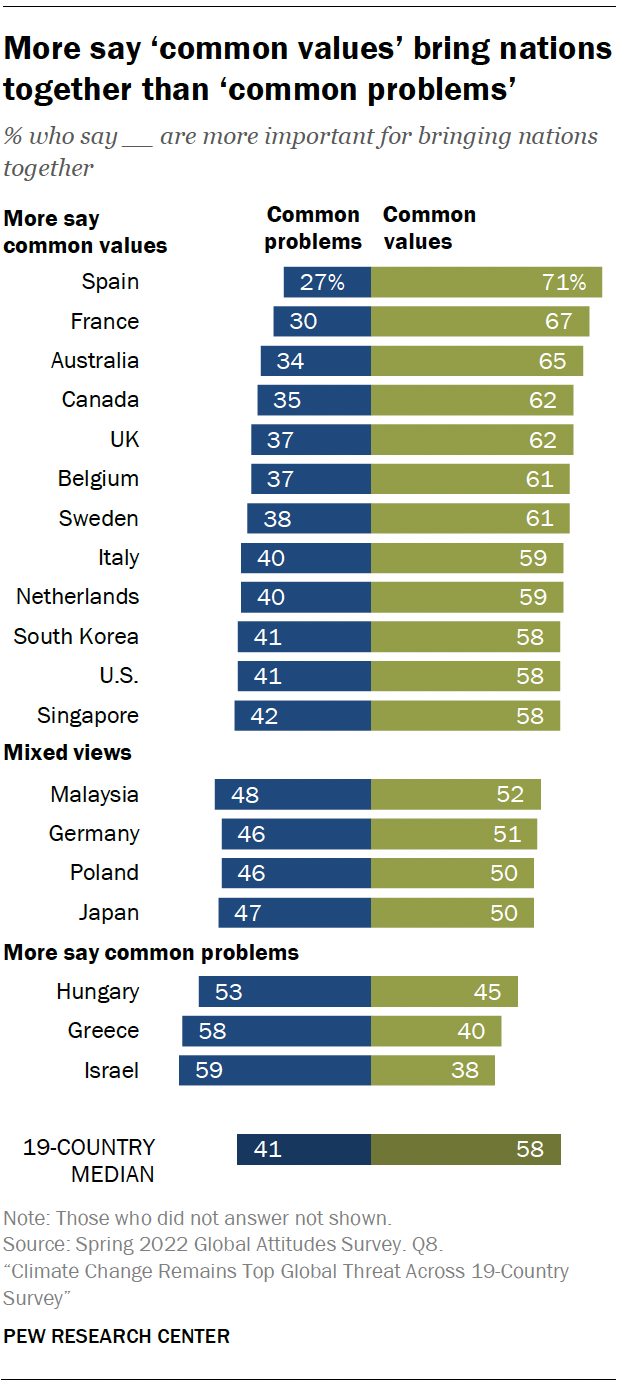

A new survey question on the efficacy of “common values” versus “common problems” for bringing the world together shows some interesting patterns, even as most say that common values are more important for bringing nations together. A median of 58% see a shared sense of values as more important for international cooperation, compared with the 41% who think nations are more brought together by shared problems.

Roughly two-thirds or more in Spain, France, and Australia say “common values” are more important for international cooperation, while about six-in-ten in Israel and Greece say “common problems” are more important. Attitudes are more mixed in Malaysia, Germany, Poland and Japan. Americans, for their part, are more likely to say common values bring countries together than common problems.

These are among the main findings of a Pew Research Center survey, conducted from Feb. 14 to June 3, 2022, among 24,525 adults in 19 nations.

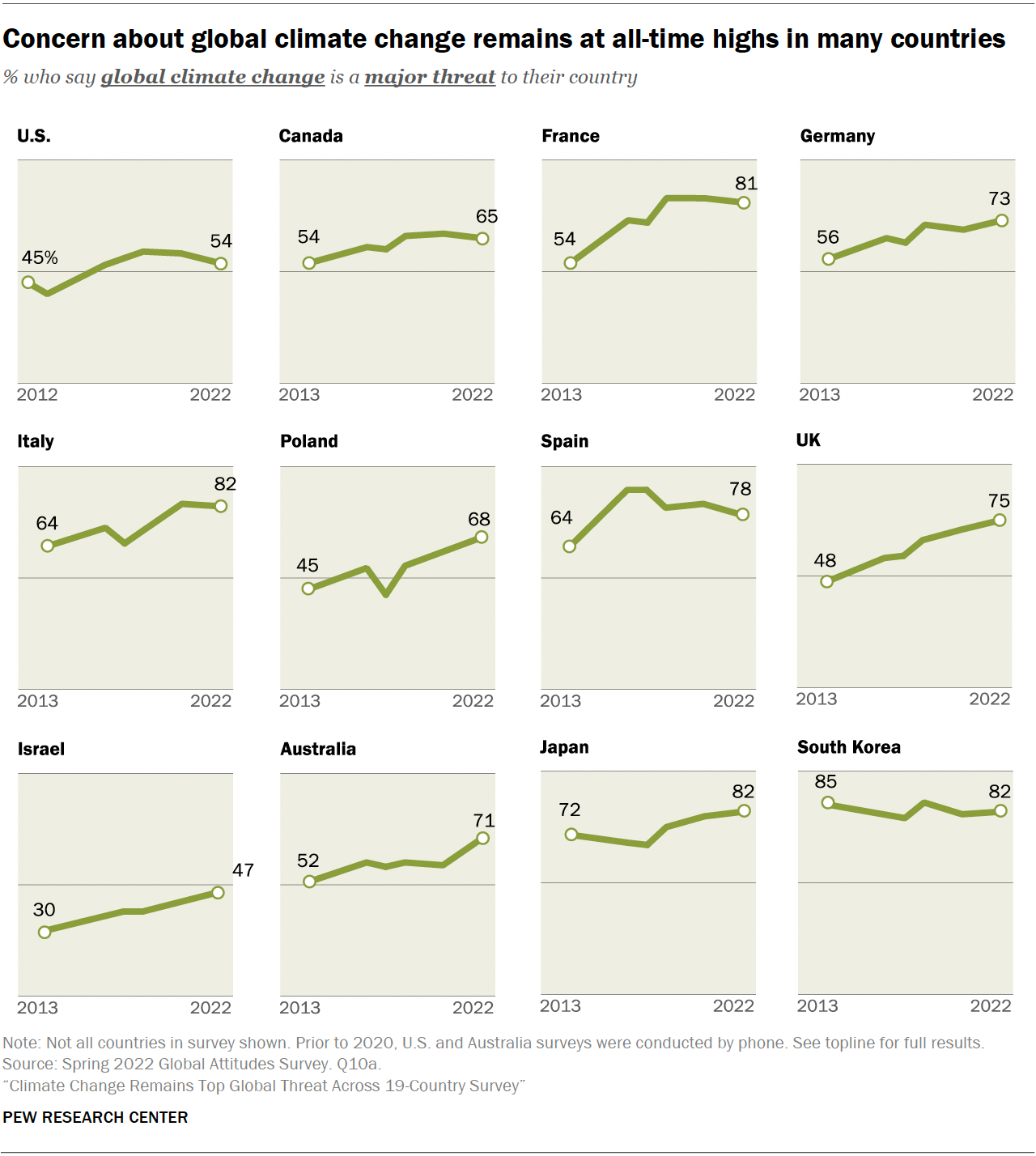

The survey finds that people continue to see climate change as one of the greatest threats to their country, and this is especially true in Europe, where more say climate change is a major threat to their country than at any time in the past decade in most countries. The results come as wildfires and extreme heat across Europe cause massive disruption to life.

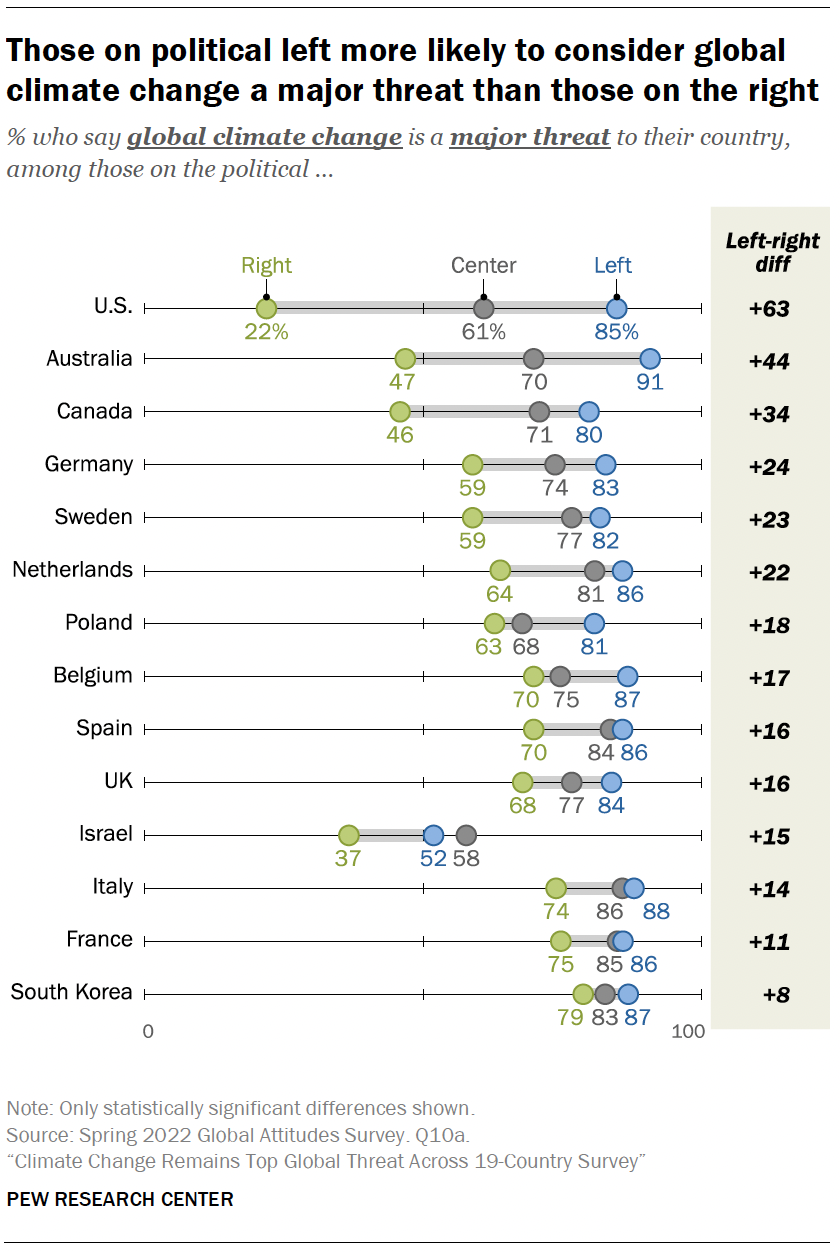

Despite the dire concerns about climate change in Europe, concerns are relatively muted in the U.S., as they have been for years. Views on climate change as a threat are linked to political divisiveness in the U.S., something also seen in the other countries surveyed, with those on the ideological left showing more concern about climate change than those on the right.

While people in these 19 countries often view climate change as the top threat, concern for the other threats tested is not diminished. Majorities in 18 of these countries view the spread of false information online and cyberattacks from other countries as major threats, even as few rank either as the top threat.

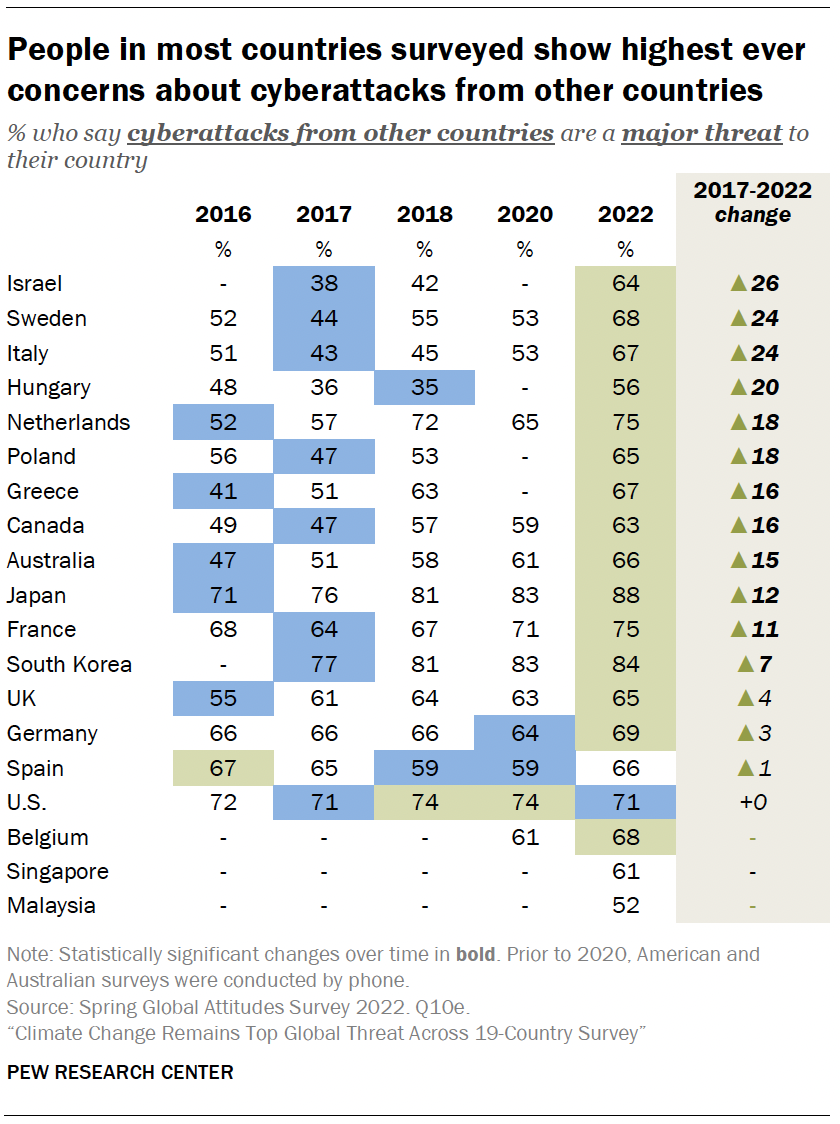

Concerns about cyberattacks, possibly heightened by the tensions between Russia and Ukraine and prominent instances of hacking across the world, are at all-time highs in many of the countries surveyed. In the last five years, there has been a remarkable increase in the share saying cyberattacks from other countries are a major threat to their country. And regarding both cyberattacks and the spread of false information online, older people are substantially more concerned than young adults in about half of the countries surveyed.

People also express worries about the condition of the global economy, as the survey was fielded just as inflation-related economic problems started to affect people across the world. Nevertheless, concerns about the global economy are high in most countries, especially among those who say their own country’s economy is bad and share pessimism about the future of children’s financial well-being.

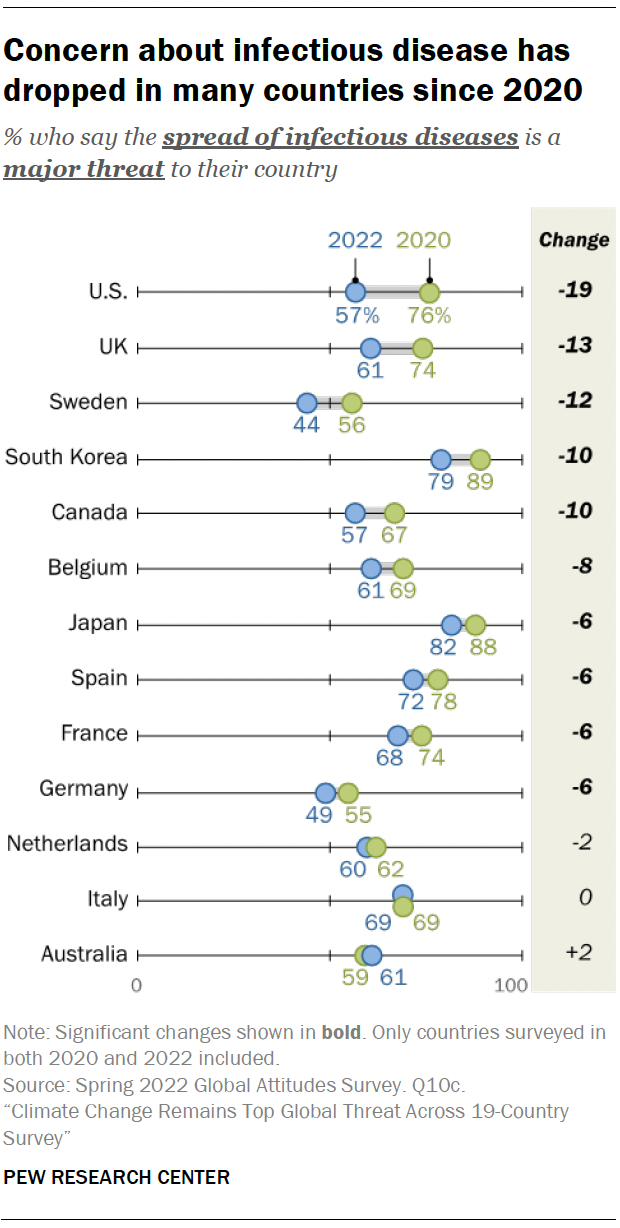

Concerns about infectious disease have dropped sharply since last year in many countries, as worldwide COVID-19 deaths have dropped in recent months. Still, majorities in all but two surveyed nations say that the spread of infectious disease is a major threat, as people continue to die from COVID-19 and concerns rise about monkeypox, which the World Health Organization declared a public health emergency of international concern.

Concerns about climate, misinformation and cyberattacks predominate across 19 countries, but people are also concerned about the global economy and spread of infectious diseases

In a year dominated by crises, both domestic and international, people in 19 countries surveyed in spring 2022 continue to view global climate change as the most serious issue. A median of 75% across these countries, mostly concentrated in Europe, North America, and the Asia-Pacific region, view global climate change as a major threat to their country. Around two-in-ten view global warming as a minor threat, while 5% do not view it as a threat.

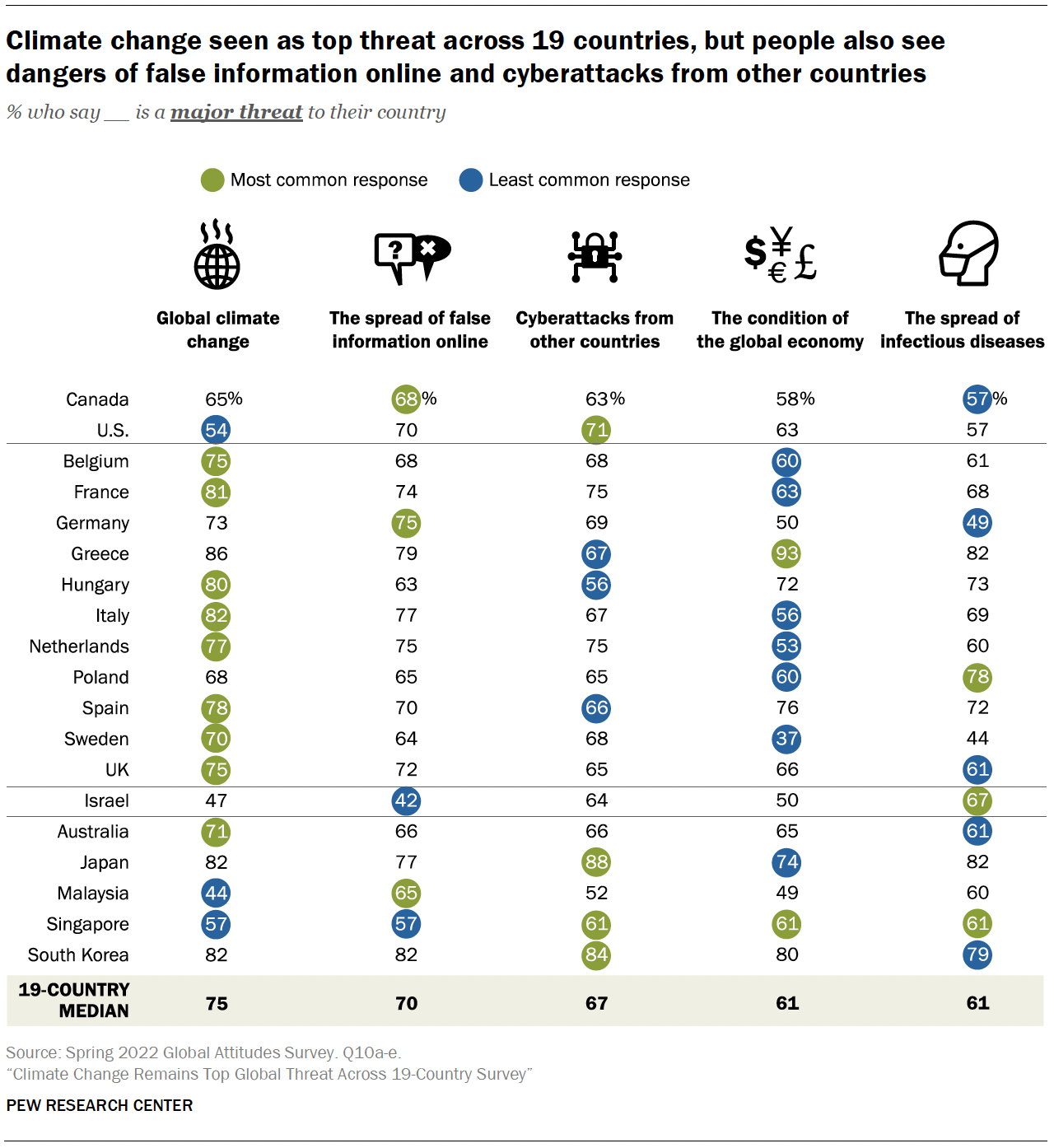

On a country-by-country basis, people in nine nations rank global climate change as the greatest threat among the five threats tested. The others are the spread of false information online, cyberattacks from other countries, the condition of the global economy and the spread of infectious diseases. Eight of these nations reside in Europe, with the other being Australia.

Concern about global warming is relatively low in Malaysia and Israel, where about half or fewer say that it is a major threat. In the U.S., 54% of people say climate change is a major threat, which is the lowest such rating among the five threats tested. Political divisions on this question play a role in how Americans assess climate change: 78% of Democrats and those that lean toward the Democratic Party say climate change is a major threat, compared with only 23% of Republicans and Republican leaners. (For more, see “Americans see different global threats facing the country now than in March 2020.”)

Political divisions on climate change are not restricted to the U.S. In 14 of the countries surveyed, those on the political left are more likely to say that climate change is a major threat than those on the political right. For example, in Australia, 91% of those who place themselves on the left side of the political spectrum say climate change is a major threat, compared with only 47% among those on the right.

These differences on climate concern also apply when comparing supporters and nonsupporters of right-wing populist parties across Europe. In virtually every European country surveyed, concerns about climate change are lower among those who support right-wing populist parties than those who do not support these parties. For example, in Germany, only 55% among supporters of Alternative for Germany (AfD) view climate change as a major threat, compared with 77% of those who do not support AfD. And in Sweden, those who support Sweden Democrats are 32 percentage points less likely to say global warming is a major threat than those who do not support the strongly populist Sweden Democrats. Similar divisions also appear in Belgium, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain and the United Kingdom.

In France and Spain, positive views of the left-wing populist parties (La France Insoumise, run by Jean-Luc Mélenchon, in France, and Podemos in Spain, led by Ione Belarra) lead to comparatively higher concern about climate change.

Despite these political divisions, concerns about climate change have been rising in recent years, as people react to the climate extremes plaguing their countries. As an example, three-quarters of Britons say that climate change is a major threat to their country in 2022. In 2013, only 48% said the same. Concerns about climate change are at all-time highs in 10 countries.

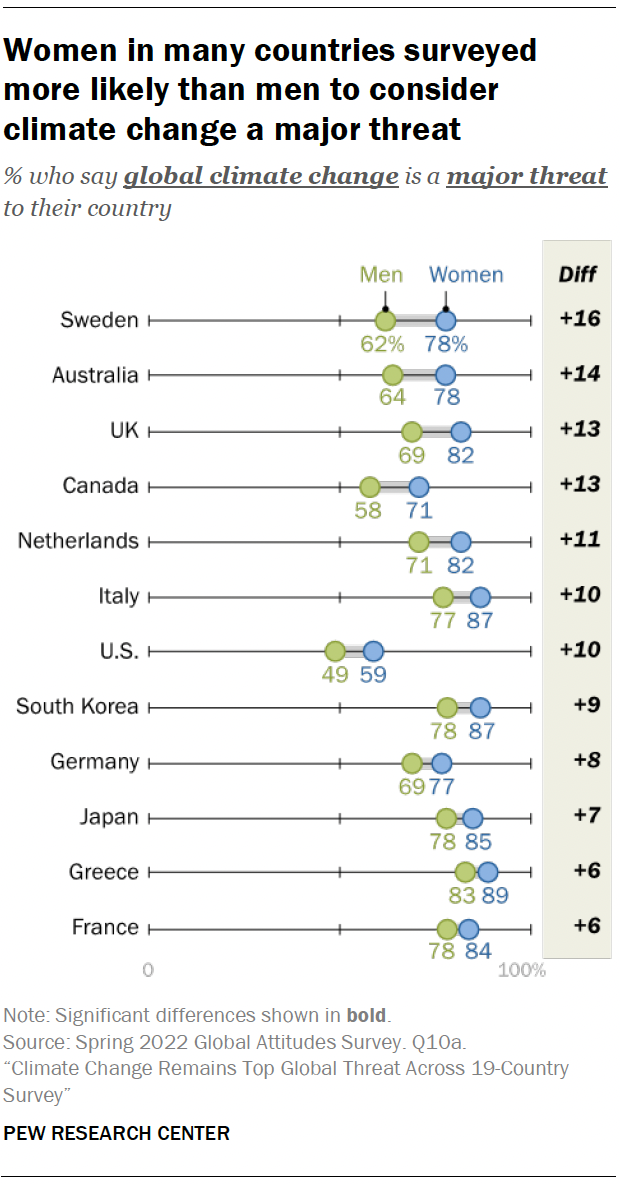

As observed in prior Pew Research Center surveys, there is a gender divide on global climate change concerns. In 12 countries, women are more likely than men to say that a changing climate is a major threat to their country. In Sweden, 78% of women, compared with 62% of men, say that climate change is a great concern. Double-digit differences of this nature are also present in Australia, the UK, Canada, the Netherlands, Italy and the U.S.

In a handful of countries, those with more education are more concerned about the threat of climate change than those with less education.1 These differences are significant in Malaysia, Poland, Israel, Australia, South Korea, Belgium and the U.S.

Age is also a factor in views of the climate threat in several countries, but the pattern is somewhat mixed. In Australia, Poland, the U.S. and France, younger people are more likely to be concerned about climate change than their elders. For example, in Australia, 85% of those ages 18 to 29 say that climate change is a major threat, compared with 63% of those 50 and older. On the other hand, older adults in Japan are more concerned about climate change than young people.

The spread of false information online and cyberattacks from other countries are the second and third greatest concerns overall among the issues tested. A median of 70% across the 19 surveyed countries see the spread of misinformation online as a top threat, with around a quarter (24%) saying it is a minor threat and 5% proclaiming disinformation as not a threat. Similarly, 67% see cyberattacks as a major threat, with a quarter saying they are a minor threat and 4% saying they are not a threat.

Three countries rank disinformation online as the top relative threat (Germany, Canada and Malaysia); four countries (Japan, South Korea, the U.S. and Singapore) view cyberattacks as one of the greatest threats.

The question on the spread of false information as a threat is new, so past trends are not available for analysis. However, concerns about cyberattacks from other countries are as high as they have been in most countries surveyed since Pew Research Center began asking the question in 2016. In fact, since 2017, concerns about cyberattacks from other countries have surged in 12 of the 16 countries where trends are available.

Take Israel, for example. In 2017, only 38% said that cyberattacks were a major threat to their country. But in 2022, when major cyberattacks have become a more common occurrence, 64% of Israelis now label attacks online as a major threat. Similar 20 percentage point or more increases in concerns about large scale hacks were also seen in Sweden, Italy and Hungary over the same period.

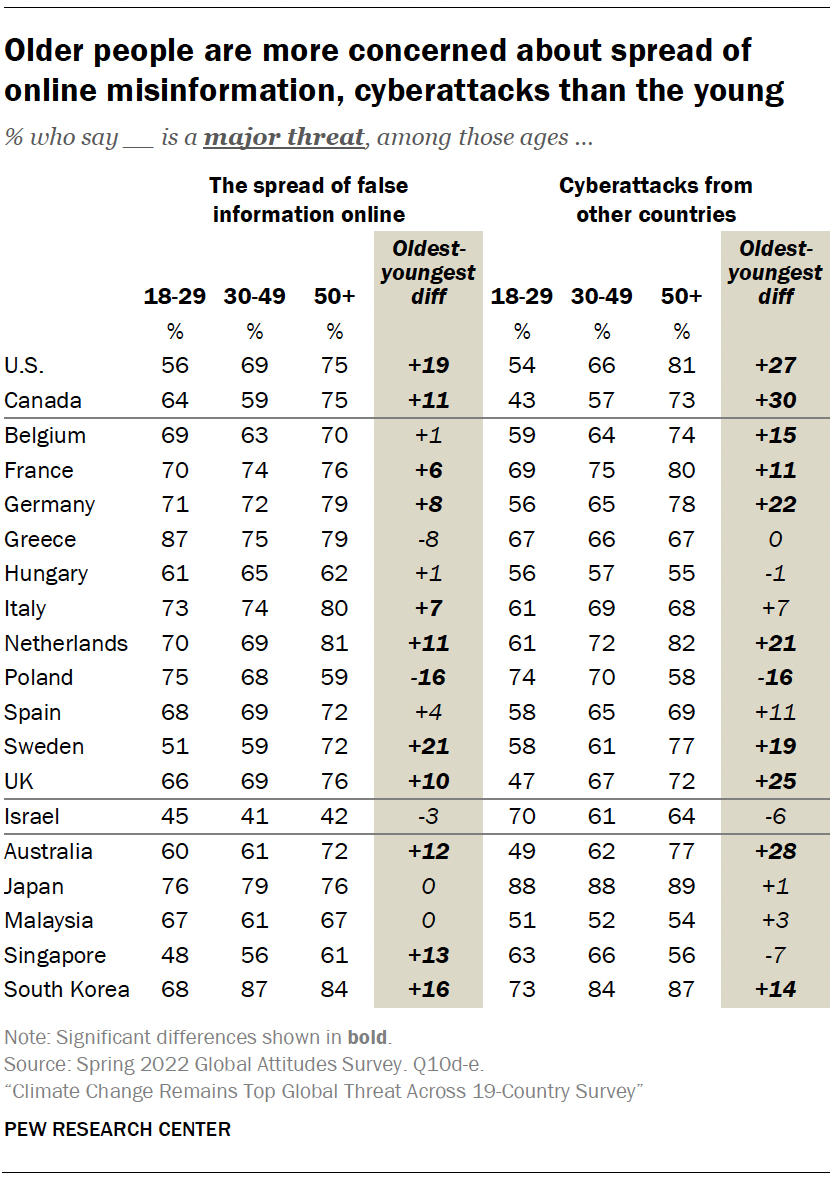

There is also a stark age divide when it comes to views about the spread of false information and cyberattacks. In many cases, people ages 50 and older are more concerned about these online threats than are 18- to 29-year-olds. And in some cases, the differences are quite substantial.

For instance, Swedes 50 and older are 21 percentage points more likely to say that the spread of false information online is a major threat than are Swedes ages 18 to 29. And three-quarters of Americans 50 and older are concerned about the spread of misinformation, compared with 56% among their younger counterparts. Younger U.S. adults are similarly less likely than older adults to say made-up news and information has a big impact on the democratic system.

Older people across a number of countries are also more concerned about cyberattacks than younger people. The differences by age are especially stark in Canada, Australia, the U.S., the UK and Germany. Only in Poland is this pattern reversed (that is, younger Poles are significantly more concerned about false information and attacks online than older Poles).

For the most part, there is not greater concern about the spread of false information and cyberattacks among social media users than those who do not use social media.

Concerns about the condition of the global economy are relatively muted among the countries surveyed, although it is important to note that the 2022 survey was fielded from Feb. 14 to June 3, as much of the world experienced rapid inflation and surging energy prices as a result of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and other economic factors related to the COVID-19 pandemic and supply chain disruptions. A median of 61% across the 19 countries view the global economy as a major threat, with about three-in-ten seeing it a minor threat and 5% saying it is not a threat.

In seven countries, concerns about the economy are the lowest among the issues tested, including only 37% in Sweden who say the economy is a major concern. That being said, concern about the world economy is up in a handful of countries since the question was last asked. The increase in concern is especially significant in Hungary and Poland, where in 2018 only around a quarter in each country said the global economy was a major concern. Now, 72% label the condition of the global economy as a major threat in Hungary and six-in-ten say the same in Poland. In addition, concerns in Greece about the global economy remain particularly high: 93% say the condition of the world economy is a major threat.

Gender plays a role in views of the world economy in nine countries. In nearly every country, women are more likely than men to say the global economy is a threat to their country. The gap is largest in Belgium, where about two-thirds of women worry about the economy, but roughly half of men say the same.

Among the strongest influences on views of the world economy as a major threat are whether people say the current economic situation in their country is good or bad, and whether people think that children today in their country will be better off or worse off in the future. In 15 countries, those who say the domestic economy is doing somewhat or very badly are more likely to say the condition of the global economy is a major threat than those who say the national economy is doing well. And in 12 countries, people who say children will be worse off financially in the future are also more likely to see the world economy as a major threat compared with those who think their children’s future is bright.

Worries about the spread of infectious disease are diminishing

Concern for the spread of infectious disease is lower in comparison to the other threats tested and has decreased in many countries since the question was last asked in 2020. Still, a median of 61% across 19 countries view infectious disease as a major threat to their country.

Majorities in most countries surveyed express worries about the spread of infectious disease. But in Germany and Sweden, only about half or fewer see it as a major threat. In fact, Germans express the least concern for infectious disease out of all the threats tested, with 49% of Germans describing it as a major threat. In Canada, the UK, Australia and South Korea, the spread of infectious disease also ranks as the least concerning of all the global threats.

In Poland, Israel and Singapore, the spread of infectious disease ranks as or is among the top threat to their respective countries. In Poland, over three-quarters of those surveyed (78%) say that infectious disease is a major threat to their country. And in Israel, 67% say the same. About six-in-ten in Singapore say disease is a major threat – the same share who say the condition of the global economy and cyberattacks are major threats.

Since the question was last asked in 2020, concern for the spread of infectious disease has dropped in most countries surveyed in both years. In the U.S., concern about the spread of infectious disease has gone down by nearly 20 percentage points, with only 57% of Americans considering it to be a major threat in 2022, while in 2020, 76% said the same. This decline in the U.S. tracks with other Pew Research Center polling on the issue. Concern about infectious disease is also down by double digits over the past two years in the UK, Sweden, South Korea and Canada.

In 16 of the countries surveyed, those who say that getting the coronavirus vaccine is important to being a good member of society are more likely to describe the spread of infectious diseases as a major threat to their country than those who do not believe receiving the coronavirus vaccine is important to being a good member of society. The largest gap can be seen in Israel, where there is a difference of nearly 40 points between those who believe the coronavirus vaccine to be important to be a good member of society (75% say the spread of infectious diseases is a major threat) and those who do not (36%). In both Australia and Canada, a similarly large difference can be observed, with a gap of 36 points present between the two groups in both countries.

In eight countries, those ages 50 and older are more likely to consider the spread of infectious diseases a major threat than their younger counterparts. In the UK, for example, 71% of Britons ages 50 and older believe the spread of infectious disease to be a major threat, while 52% of adults under 30 say the same.

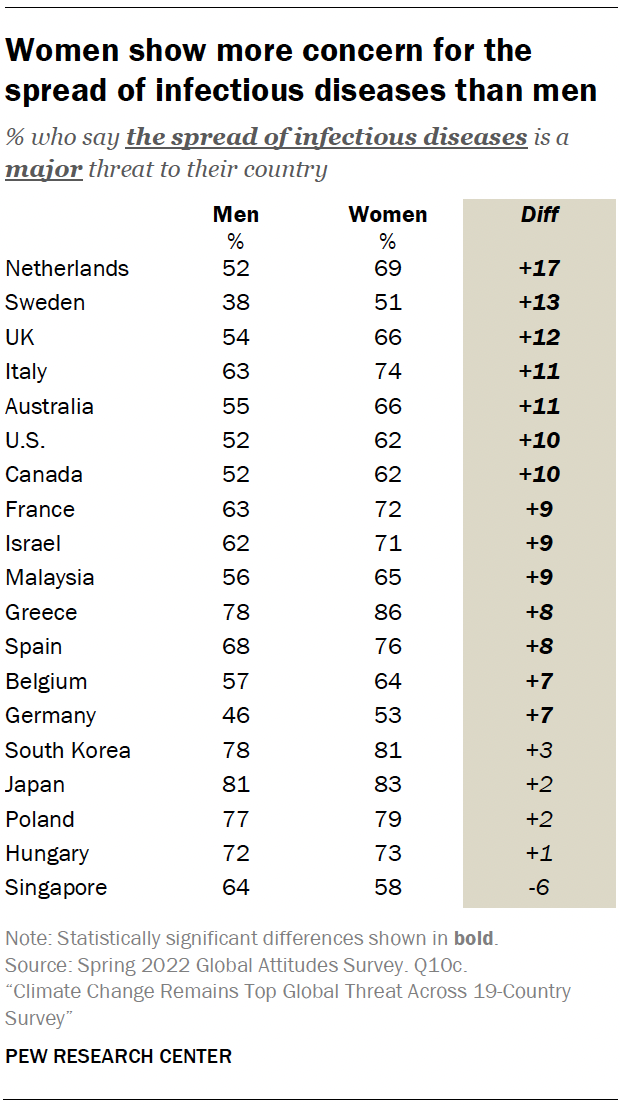

Responses also vary between men and women in many countries, with women consistently expressing greater concern for the spread of infectious diseases than men. This gap is most distinct in the Netherlands, where around seven-in-ten women say that the spread of infectious diseases is a major threat to their country, while half of men say the same – a difference of 17 points.

And in eight countries, those with less education are more likely to describe the spread of infectious diseases to be a major threat to their country than those with more education. In Hungary, about three-quarters of those with less education consider the spread of infectious diseases to be a major threat, while 60% of those with more education say the same. The opposite relationship is seen in Malaysia, where 58% of those with less education consider infectious diseases to be a major threat, compared with the 74% of those with more education who say the same.

UN seen in a positive light by most across 19 nations polled

The United Nations is seen more favorably than unfavorably across most of the countries surveyed in 2022. A median of 65% express a positive opinion of the multilateral organization, compared with 27% who have an unfavorable view.

In the two North American countries surveyed – Canada and the U.S. – majorities give the UN favorable ratings.

Americans are similarly positive on the benefits of UN membership writ large: About two-thirds (66%) say the U.S. benefits a great deal or a fair amount from being a member of the UN. But, according to a May 2022 survey, relatively few Americans say the UN’s influence in the world has been getting stronger in recent years. Just 16% expressed this view, while 39% said the UN’s influence was getting weaker and 43% said it was staying about the same.

Across the European countries surveyed, the image of the UN is largely positive. About seven-in-ten or more in Poland, Sweden, the UK, Germany, the Netherlands and Italy view the UN in a favorable light. However, Greeks are notably split in their views: 45% express a favorable opinion, while 49% express an unfavorable opinion.

Seven-in-ten Israelis have an unfavorable view of the UN – the highest negative rating observed across the 19 countries surveyed. Israeli views of the UN are influenced by ethnicity: Arabs are more than twice as likely as Jews to see the UN in a positive light (44% vs. 21%, respectively).

Opinion of the UN in the Asia-Pacific region is generally more positive than negative. Majorities in South Korea, Australia, Malaysia and Singapore give the UN favorable ratings. Opinion is somewhat more negative in Japan: 48% express a negative view, compared with 40% who express a positive one. Still, this represents an overall improvement in Japanese opinion of the UN, which reached an all-time low of 29% favorable in the summer of 2020.

In South Korea (+8 percentage points) and the UK (+5), favorable opinion of the UN has increased measurably from 2021. A more positive outlook toward the UN has also occurred in two countries not surveyed since 2019: Hungary (+11) and Poland (+6). However, positive views of the UN have declined significantly in Singapore (-9), Spain (-7), Italy (-6) and Canada (-5) since 2021.

Opinion of the UN is partially shaped by ideological affiliation. In seven countries, those who place themselves on the ideological left are more likely than those who place themselves on the right to express a positive view of the UN. This difference is largest in the U.S., where liberals are twice as likely as conservatives to hold a favorable view of the UN (80% vs. 40% respectively). And double-digit differences of this nature are also present in Israel, Canada, Hungary, Australia, Italy and Germany. In Greece, however, this pattern is reversed: Half of those on the right have a positive opinion of the UN, compared with 32% of those on the left.

Age and education also impact opinion of the UN. As observed in prior Pew Research Center surveys, adults ages 18 to 29 tend to have more favorable views of the UN than those 50 and older. In Hungary, for example, young adults are 20 percentage points more likely than older adults to express a positive opinion toward the UN. A similar pattern is observed across several other countries in the Asia-Pacific region, Europe and Israel.

Those with a postsecondary education or more in seven countries are more likely than those with a secondary education or less to express favorable views of the UN. Among Belgians, 74% of those with more education have a positive take on the UN, compared with 62% of Belgians with less education. In Malaysia, however, those with less education are more likely to have a positive opinion of the UN than those with more education (66% vs. 56% respectively).

In several European countries, those with a favorable view of that country’s right-wing populist party are more likely to hold a negative view of the UN than those who are unfavorable toward populist parties. In Germany, for example, 44% of those with a favorable view of Alternative for Germany (AfD) express an unfavorable view of the UN, compared with 21% of those with an unfavorable view of AfD who say the same.

Most say that many of the problems facing their country can be solved by working with other countries

A median of 64% across 19 countries say that many of the problems facing their country can be solved by working with other countries, while 31% say that few such problems can be solved by working with other countries. The sentiment that international cooperation can solve many of the country’s problems is highest in Sweden, where more than eight-in-ten say this.

The same faith in international cooperation rings true in most of the European countries surveyed. In the Netherlands, Italy, Spain, Germany and the UK, at least seven-in-ten say that many of the problems facing their country can be solved by working with other countries. A median of 70% across the 11 European countries surveyed think international cooperation can solve many of the domestic problems people face.

Views in North America and the Asia-Pacific region are more divided. Only about half of adults in both the U.S. and Canada believe most of the problems facing their country can be solved through international cooperation. Majorities in Japan, Australia and South Korea say the same, but in Malaysia, only 49% agree.

In many countries, views vary by education. Those with more education are more likely to say that many of the problems facing their country can be solved by working with other countries in 11 countries, such as in France, where nearly three-quarters of those with a higher education level say this, as opposed to the 61% of those with a lower education level.

Ideology also plays a role in people’s views on the ability of international cooperation to solve problems. In 10 countries, those on the left are more likely than those on the right to say that many of the problems facing their country can be solved by working with other nations. This difference is most starkly seen in the U.S., where the gap between the liberals and conservatives is over 30 percentage points. (For more on American views of international cooperation, see “Americans are divided over U.S. role globally and whether international engagement can solve problems.”)

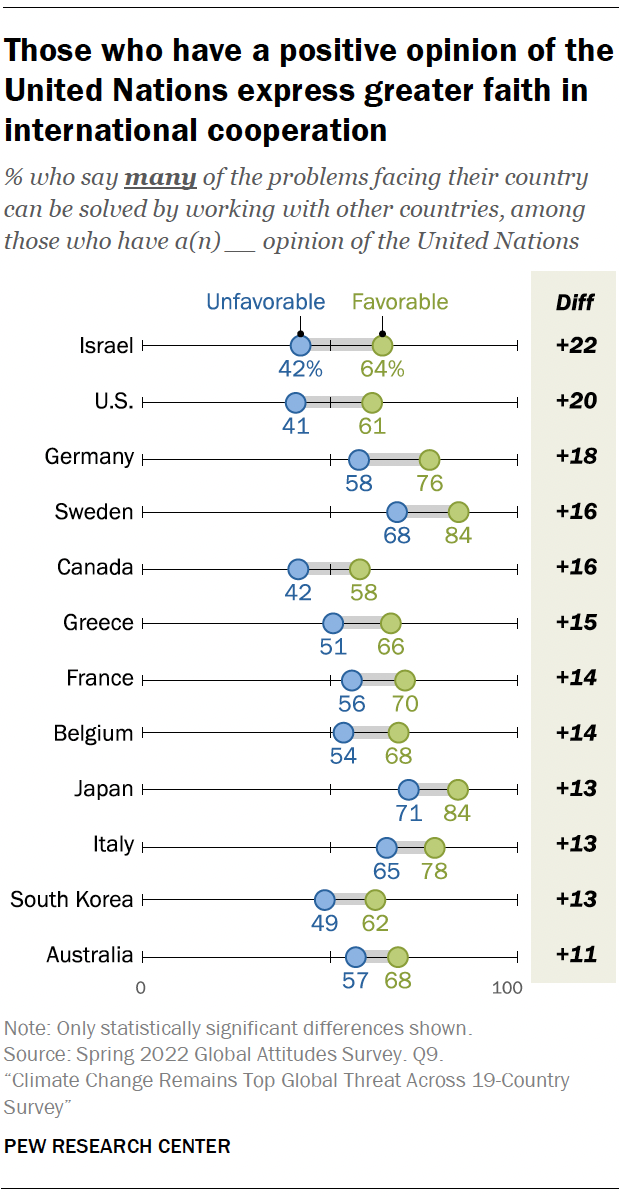

In 12 countries, views on international cooperation also vary by impressions of the UN, with those who feel favorably toward the UN more likely to say that many problems in their country can be solved by working with other countries. In all 12 nations, there is a double-digit difference between those who feel favorably toward the UN and those who do not. For instance, in Japan, 84% who have a positive opinion of the UN also express a belief that their country’s problems can be solved by working with other countries, while 71% of those who have an unfavorable opinion of the UN say the same.

‘Common values’ generally seen as bringing nations together more than ‘common problems’

Across many of the 19 countries surveyed, larger shares say that common values are more important for bringing nations together than say common problems are more important.

Majorities in 12 countries say common values are more important to international cooperation, including about two-thirds or more in Spain, France and Australia. Countries where more hold the view that common values bring countries together span Europe, the Asia-Pacific region and North America.

Views on the importance of values or problems for bringing countries together are somewhat mixed in Malaysia, Germany, Poland and Japan. Nearly equal shares in these countries say either common values or problems are more important for global cooperation.

Only in three countries surveyed do more than half say common problems are important for bringing nations together: Israel, Greece and Hungary.

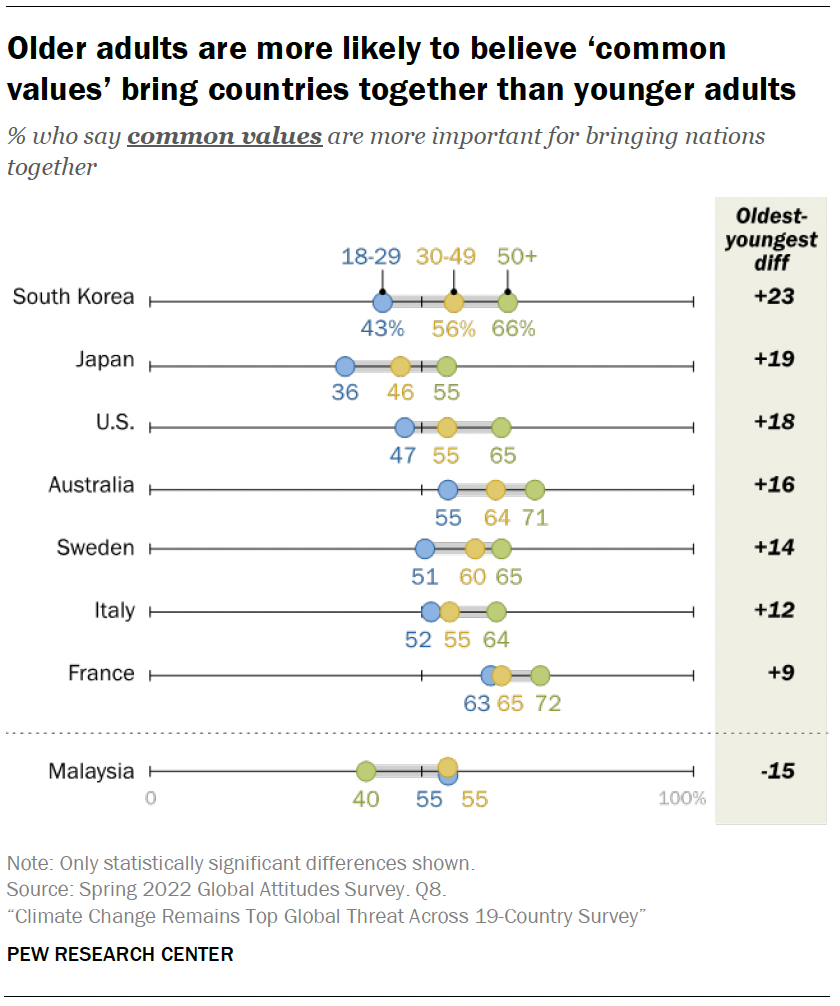

In seven countries, adults ages 50 and older are more likely to say common values are more important for bringing nations together than those ages 18 to 29. Younger adults are, on the other hand, more likely to cite common problems as important for international cooperation than their older counterparts. In South Korea, for example, older adults are 23 percentage points more likely than those 18 to 29 to say common values bring countries together.

In Malaysia, however, the pattern is reversed. Young adults are more likely to say common values bring nations together, while older adults are more likely to say common problems encourage international cooperation.