I. Overview and Executive Summary

This is part of a Pew Research Center series of reports exploring the behaviors, values and opinions of the teens and twenty-somethings that make up the Millennial Generation

Updated Edition, July 01, 2013

Hispanics are the largest and youngest minority group in the United States. One- in-five schoolchildren is Hispanic. One-in-four newborns is Hispanic. Never before in this country’s history has a minority ethnic group made up so large a share of the youngest Americans. By force of numbers alone, the kinds of adults these young Latinos become will help shape the kind of society America becomes in the 21st century.

This report takes an in-depth look at Hispanics who are ages 16 to 25, a phase of life when young people make choices that—for better and worse—set their path to adulthood. For this particular ethnic group, it is also a time when they navigate the intricate, often porous borders between the two cultures they inhabit—American and Latin American.

The report explores the attitudes, values, social behaviors, family characteristics, economic well-being, educational attainment and labor force outcomes of these young Latinos. It is based on a new Pew Hispanic Center telephone survey of a nationally representative sample of 2,012 Latinos, supplemented by the Center’s analysis of government demographic, economic, education and health data sets.

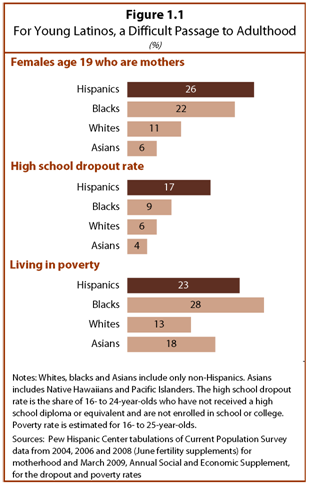

The data paint a mixed picture. Young Latinos are satisfied with their lives, optimistic about their futures and place a high value on education, hard work and career success. Yet they are much more likely than other American youths to drop out of school and to become teenage parents. They are more likely than white and Asian youths to live in poverty. And they have high levels of exposure to gangs.

These are attitudes and behaviors that, through history, have often been associated with the immigrant experience. But most Latino youths are not immigrants. Two-thirds were born in the United States, many of them descendants of the big, ongoing wave of Latin American immigrants who began coming to this country around 1965.

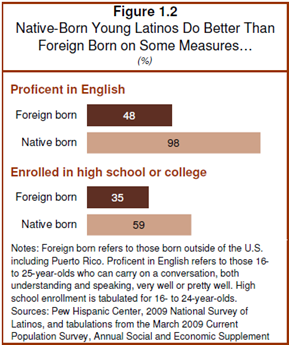

As might be expected, they do better than their foreign-born counterparts on many key economic, social and acculturation indicators analyzed in this report. They are much more proficient in English and are less likely to drop out of high school, live in poverty or become a teen parent.

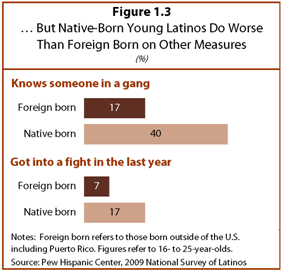

But on a number of other measures, U.S.-born Latino youths do no better than the foreign born. And on some fronts, they do worse.

For example, native-born Latino youths are about twice as likely as the foreign born to have ties to a gang or to have gotten into a fight or to have carried a weapon in the past year. They are also more likely to be in prison.

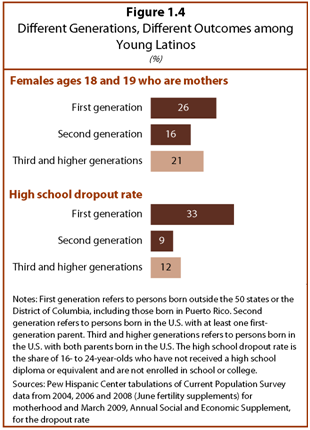

The picture becomes even more murky when comparisons are made among youths who are first generation (immigrants themselves), second generation (U.S.-born children of immigrants) and third and higher generation (U.S.-born grandchildren or more far-removed descendants of immigrants).1

For example, teen parenthood rates and high school dropout rates are much lower among the second generation than the first, but they appear higher among the third generation than the second. The same is true for poverty rates.

Identity and Assimilation

Throughout this nation’s history, immigrant assimilation has always meant something more than the sum of the sorts of economic and social measures outlined above. It also has a psychological dimension. Over the course of several generations, the immigrant family typically loosens its sense of identity from the old country and binds it to the new.

It is too soon to tell if this process will play out for today’s Hispanic immigrants and their offspring in the same way it did for the European immigrants of the 19th and early 20th centuries. But whatever the ultimate trajectory, it is clear that many of today’s Latino youths, be they first or second generation, are straddling two worlds as they adapt to the new homeland.

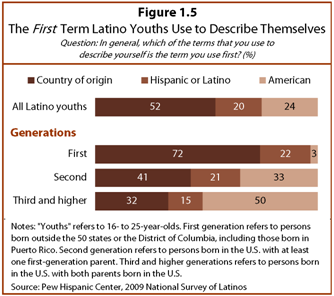

According to the Pew Hispanic Center’s National Survey of Latinos, more than half (52%) of Latinos ages 16 to 25 identify themselves first by their family’s country of origin, be it Mexico, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, El Salvador or any of more than a dozen other Spanish-speaking countries. An additional 20% generally use the terms “Hispanic” or “Latino” first when describing themselves. Only about one-in-four (24%) generally use the term “American” first.

Among the U.S.-born children of immigrants, “American” is somewhat more commonly used as a primary term of self-identification. Even so, just 33% of these young second generation Latinos use American first, while 21% refer to themselves first by the terms Hispanic or Latino, and the plurality—41%—refer to themselves first by the country their parents left in order to settle and raise their children in this country.

Only in the third and higher generations do a plurality of Hispanic youths (50%) use “American” as their first term of self-description.

Immigration in Historical Perspective

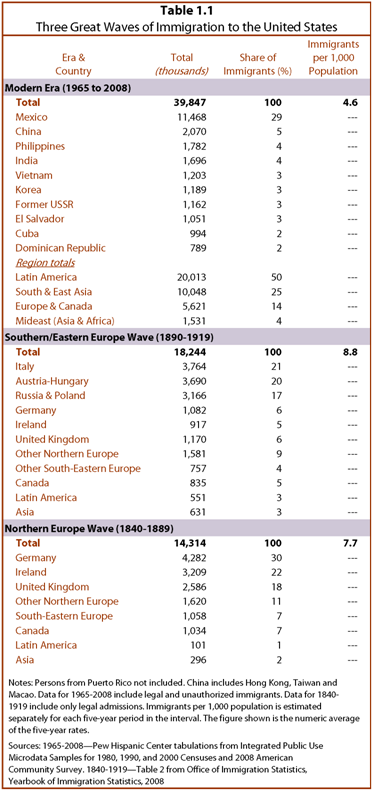

Measured in raw numbers, the modern Latin American-dominated immigration wave is by far the largest in U.S. history. Nearly 40 million immigrants have come to the United States since 1965. About half are from Latin America, a quarter from Asia and the remainder from Europe, Canada, the Middle East and Africa. By contrast, about 14 million immigrants came during the big Northern and Western European immigration wave of the 19th century and about 18 million came during the big Southern and Eastern European-dominated immigration wave of the early 20th century.2

However, the population of the United States was much smaller during those earlier waves. When measured against the size of the U.S. population during the period when the immigration occurred, the modern wave’s average annual rate of 4.6 new immigrants per 1,000 population falls well below the 7.7 annual rate that prevailed in the mid- to late 19th century and the 8.8 rate at the beginning of the 20th century.

All immigration waves produce backlashes of one kind or another, and the latest one is no exception. Illegal immigration, in particular, has become a highly-charged political issue in recent times. It is also a relatively new phenomenon; past immigration waves did not generate large numbers of illegal immigrants because the U.S. imposed fewer restrictions on immigration flow in the past than it does now.

The current wave may differ from earlier waves in other ways as well. More than a few immigration scholars have voiced skepticism that the children and grandchildren of today’s Hispanic immigrants will enjoy the same upward mobility experienced by the offspring of European immigrants in previous centuries.3

Their reasons vary, and not all are consistent with one another. Some scholars point to structural changes in modern economies that make it more difficult for unskilled laborers to climb into the middle class. Some say the illegal status of so many of today’s immigrants is a major obstacle to their upward mobility. Some say the close proximity of today’s sending countries and the relative ease of modern global communication reduce the felt need of immigrants and their families to acculturate to their new country. Some say the fatalism of Latin American cultures is a poor fit in a society built on Anglo-Saxon values. Some say that America’s growing tolerance for cultural diversity may encourage modern immigrants and their offspring to retain ethnic identities that were seen by yesterday’s immigrants as a handicap. (The melting pot is dead. Long live the salad bowl.) Alternatively, some say that Latinos’ brown skin makes assimilation difficult in a country where white remains the racial norm.

It will probably take at least another generation’s worth of new facts on the ground to know whether these theories have merit. But it is not too soon to take some snapshots and lay down some markers. This report does so by assembling a wide range of empirical evidence (some generated by our own new survey; some by our analysis of government data) and subjecting it to a series of comparisons: between Latinos and non-Latinos; between young Latinos and older Latinos; between foreign-born Latinos and native-born Latinos; and between first, second, and third and higher generations of Latinos.

The generational analyses presented here do not compare the outcomes of individual Latino immigrants with those of their own children or grandchildren. Instead, our generational analysis compares today’s young Latino immigrants with today’s children and grandchildren of yesterday’s immigrants. As such, the report can provide some insights into the intergenerational mobility of an immigrant group over time. But it cannot fully disentangle the many factors that may help explain the observed patterns—be they compositional effects (the different skills, education levels and other forms of human capital that different cohorts of immigrants bring) or period effects (the different economic conditions that confront immigrants in different time periods).

Readers should be especially careful when interpreting findings about the third and higher generation, for this is a very diverse group. We estimate that about 40% are the grandchildren of Latin American immigrants, while the remainder can trace their roots in this country much farther back in time.

For some in this mixed group, endemic poverty and its attendant social ills have been a part of their families, barrios and colonias for generations, even centuries. Meantime, others in the third and higher generation have been upwardly mobile in ways consistent with the generational trajectories of European immigrant groups. Because the data we use in this report do not allow us to separate out the different demographic sub-groups within the third and higher generation, the overall numbers we present are averages that often mask large variances within this group.

A summary of the major findings of the report:

Demography

- Two-thirds of Hispanics ages 16 to 25 are native-born Americans. That figure may surprise those who think of Latinos mainly as immigrants. But the four-decade-old Hispanic immigration wave is now mature enough to have spawned a big second generation of U.S.-born children who are on the cusp of adulthood. Back in 1995, nearly half of all Latinos ages 16 to 25 were immigrants. This year marks the first time that a plurality (37%) of Latinos in this age group are the U.S.-born children of immigrants. An additional 29% are of third-and-higher generations. Just 34% are immigrants themselves.

- Hispanics are not only the largest minority population in the United States, they are also the youngest. Their median age is 27, compared with 31 for blacks, 36 for Asians and 41 for whites. One-quarter of all newborns in the United States are Hispanic.

-

About 17% of all Hispanics and 22% of all Hispanic youths ages 16 to 25 are unauthorized immigrants, according to Pew Hispanic Center estimates. Some 41% of all foreign-born Hispanics and 58% of foreign-born Hispanic youths are estimated to be unauthorized immigrants.

- Latinos make up about 18% of all youths in the U.S. ages 16 to 25. However, their share is far higher in a number of states. They make up 51% of all youths in New Mexico, 42% in California, 40% in Texas, 36% in Arizona, 31% in Nevada, 24% in Florida, and 24% in Colorado.

- More than two-thirds (68%) of young Latinos are of Mexican heritage. They are growing up in families that on average have less “educational capital” than do other Latinos. More than four-in-ten young Latinos of Mexican origin say their mothers (42%) and fathers (44%) have less than a high school diploma, compared with about one-quarter of non-Mexican-heritage young Latinos who say the same.

Identity and Parental Socialization

- Asked which term they generally use first to describe themselves, young Hispanics show a strong preference for their family’s country of origin (52%) over American (24%) or the terms Hispanic or Latino (20%). Among the U.S.-born children of immigrants, the share that identifies first as American rises to one-in-three, and among the third and higher generations, it rises to half.

- Young Hispanics are being socialized in a family setting that places a strong emphasis on their Latin American roots. More say their parents have often spoken to them of their pride in their family’s country of origin than say their parents have often talked to them of their pride in being American—42% versus 29%. More say they have often been encouraged by their parents to speak in Spanish than say they have often been encouraged to speak only in English—60% versus 22%. The survey also finds that the more likely young Latinos are to receive these kinds of signals from their parents, the more likely they are to refer to themselves first by their country of origin.

- By a ratio of about two-to-one, young Hispanics say there are more cultural differences (64%) than commonalities (33%) within the Hispanic community in the U.S. At the same time, about two-thirds (64%) say that Latinos from different countries get along well with each other in the U.S., while about one-third say they do not.

- Most young Hispanics do not see themselves fitting into the race framework of the U.S. Census Bureau. More than three-in-four (76%) say their race is “some other race” or volunteer that their race is “Hispanic or Latino.” Young Hispanics also do not see their race in the same way as Hispanics ages 26 and older. Only 16% of Hispanic youths identify themselves as white, while nearly twice as many (30%) older Hispanics identify their race as white.

Language

- About one-third (36%) of Latinos ages 16 to 25 are English dominant in their language patterns, while 41% are bilingual and 23% are Spanish dominant.

- The language usage patterns of Latinos change dramatically from the immigrant generation to the native born. Among foreign-born Latinos ages 16 to 25, just 48% say they can speak English very well or pretty well. Among their native-born counterparts, that figures doubles to 98%.

- For the children of immigrants and later generations, embracing English does not necessarily mean abandoning Spanish. Fully 79% of the second generation and 38% of the third report that they are proficient in speaking Spanish. These figures are below the share of immigrant youths who are proficient in Spanish (89%), but they demonstrate the resilience of the mother tongue for several generations after immigration.

- For both native-born and foreign-born young Hispanics, the boundaries between English and Spanish are permeable. Seven-in-ten (70%) say that when speaking with family members and friends, they often or sometimes use a hybrid known as “Spanglish” that mixes words from both languages.

Teenage Parenthood

- Young Hispanic females have the highest rates of teen parenthood of any major racial or ethnic group in the country. According to the Center’s analysis of Census data, about one-in-four young Hispanic females (26%) becomes a mother by age 19. This compares with a rate of 22% among young black females, 11% among young white females, and 6% among young Asian females.

- Notwithstanding those numbers, the rate of births to Hispanic females ages 15 to 19 declined by 18% from 1990 to 2007. But among the full population, the rate of births to teenagers in this age group declined by 29% during the same period.

- A heavy majority of older Latinos (81%) and Latino youths (75%) say that more teenage girls having babies is a bad thing for society. Even higher shares of the full U.S. population say the same thing—94% of all adults and 90% of all 18- to 25-year-olds.

- About seven-in-ten (69%) Latino youths say that becoming a teen parent prevents a person from reaching one’s goals in life; 28% disagree.

- Native-born Latino youths have a somewhat more negative view of teen parenthood than do the foreign born. Some 71% of the second generation and 78% of the third say teen parenthood interferes with one’s goals in life. Just 62% of foreign-born youths agree. The pattern is the same on the question of whether more teen parenthood is bad for society.

- On average, Hispanic females are projected to have just over three children in their lifetime. In comparison, African-American women are projected to have an average of 2.15 children in their lifetime, and for whites this number is 1.86.

Life Priorities and Satisfaction

- Like most youths, young Latinos express high levels of satisfaction with their lives, with half saying they are “very” satisfied and 45% saying they are “mostly” satisfied. They are also optimistic about their futures. More than seven-in-ten (72%) expect to be better off financially than their parents, while just 4% expect to be worse off. Optimism on this question runs a bit higher among native-born Latinos (75%) than among the foreign born (66%).

- Even more so than other youths, young Latinos have high aspirations for career success. Some 89% say it is very important in their lives, compared with 80% of the full population of 18- to 25-year-olds who say the same.

- Other life priorities rank a bit lower among Latino youths. About half say that having children (55%), living a religious life (51%) and being married (48%) are very important to their lives; about a quarter (24%) say the same about being wealthy. All of these ratings are very similar to those made by non-Latino youths.

- Latinos believe in the rewards of hard work. More than eight-in-ten—including 80% of Latino youths and 86% of Latinos ages 26 and older—say that most people can get ahead in life if they work hard.

- Nearly four-in-ten (38%) young Latinos say they, a relative or close friend has been the target of ethnic or racial discrimination. This is higher than the share of older Latinos who say the same (31%). Also, perceptions of discrimination are more widespread among native-born (41%) than foreign-born (32%) young Latinos.

Educational Expectations and Attainment

- The high school dropout rate among Latino youths (17%) is nearly three times as high as it is among white youths (6%) and nearly double the rate among blacks (9%). Rates for all groups have been declining for decades.

- The high school dropout rate for the second generation of Latino youth (9%) is higher than the rate for whites (6%) and Asians (4%) but comparable to the rate for blacks (9%).

- Nearly all Latino youths (89%) and older adults (88%) agree with the statement that a college degree is important for getting ahead in life. However, just under half of Latinos ages 18 to 25 say they plan to get a college degree.

- The reason most often given by Latino youths who cut off their education before college is financial pressure to support a family. Nearly three-quarters of this group say this is a big reason for not continuing in school. About half cite poor English skills; about four-in-ten cite a dislike of school or a belief that they do not need more education for the careers they plan to pursue.

- Native-born Latino youths go much farther in school than do their foreign-born counterparts. Among 16- to 24-year-olds who were born abroad, just 21% are enrolled in high school. Among their native-born counterparts, 38% of second-generation and 32% of third-generation young Latinos are enrolled in high school.

- The high school completion rate (89%) and the college enrollment rate (46%) for second generation Latino youths are similar to those of whites in this cohort, 94% of whom have completed high school and 46% of whom are enrolled in college. However, second generation Latinos who attend college are only about half as likely as white college students to complete a bachelor’s degree (Fry, 2002).

Economic Well-Being

- The household income of young Latinos lags well behind that of young whites and is slightly ahead of young blacks. Poverty rates follow the same pattern: Some 23% of young Latinos live in poverty, compared with 13% of young whites and 28% of young blacks.

- The poverty rate among young Latinos declines significantly from the first generation (29%) to the second (19%). The rate for the third and higher generations is 21%.

- Foreign-born Latino youths are more likely to be working or looking for work than the native born (64% versus 56%) and have lower rates of unemployment (17% versus 23%). Labor market activity and unemployment among foreign-born Latino youths match that of all youth.

- Foreign-born Latino youths are much more likely than their native-born counterparts to be employed in lower-skill occupations. More than half (52%) of all employed foreign-born youths are in food preparation and serving; construction and extraction; building, grounds cleaning and maintenance; and production occupations, compared with 27% of native-born Latino youths. The native born are more dispersed across occupations, including in relativity high-skill occupations.

Gangs, Fights, Weapons, Jail

- About three-in-ten (31%) young Latinos say they have a friend or relative who is a current or former gang member. This degree of familiarity with gangs is much more prevalent among the native born than the foreign born—40% versus 17%.

- The same pattern applies to other risk behaviors explored in the survey. Some 17% of native-born Latino youths say they got into a fight in the past year, compared with just 7% of foreign-born youths. Some 7% of the native born say they carried a weapon in the past year, more than double the 3% share of foreign born who say the same. And 26% of the native born say they were questioned by police for any reason in the past year, compared with 15% of the foreign born.

- Mexican-heritage young Latinos have more experience with gangs than other young Latinos. More than half (56%) say gangs were in their schools, while just four-in-ten (40%) other young Latinos say the same. In addition, young Latinos of Mexican origin are nearly twice as likely as other young Latinos to say that a friend or a relative is a member of a gang—37% versus 19%.

- About 3% of young Hispanic males (ages 16 to 25) were incarcerated in 2008, compared with 7% of young black males and 1% of young white males. Native-born young male Hispanics are more likely than their foreign-born counterparts to be incarcerated—3% versus 2%.

About this Report

This report is the work of the entire Pew Hispanic Center staff. The overview (Chapter 1) was written by the Center’s Director Paul Taylor, who also served as overall editor. Chapters 2 and 5 were written by Associate Director for Research Rakesh Kochhar. Chapters 4 and 8 were written by Senior Researcher Gretchen Livingston. Chapters 3 and 7 were written by Associate Director Mark Hugo Lopez. Chapter 6 was written by Kochhar and Lopez. Chapter 9 was written by Rich Morin, Senior Editor of the PewResearchCenter’s Social & Demographic Trends project (www.pewresearch.org/pewresearch-org/social-trends), and Senior Research Associate Richard Fry. Senior Demographer Jeffrey S. Passel tabulated immigration statistics and provided guidance on the demographic portions of this report. The topline was compiled by Daniel Dockterman and Gabriel Velasco. The report was copy-edited by Marcia Kramer of Kramer Editing Services. It was number checked by Daniel Dockterman, Gabriel Velasco and Wendy Wang.

Lopez took the lead in developing the survey questionnaire, assisted by the colleagues listed above and also by Ana González-Barrera, Jennifer Medina, Cristina Mercado and Kim Parker. The authors also thank González-Barrera for helping to compile demographic statistics and Mercado for helping to coordinate the focus groups and transcribe focus group recordings. Daniel Dockterman and Gabriel Velasco provided outstanding support for the production of the report.

About the Survey

The 2009 National Survey of Latinos was conducted from Aug. 5 through Sept. 16, 2009, among a randomly selected, nationally representative sample of 2,012 Hispanics ages 16 and older, with an oversample of 1,240 Hispanics ages 16 to 25. The survey was conducted in both English and Spanish, on cellular as well as landline telephones. The margin of error for the full sample is plus or minus 3.7 percentage points at the 95% confidence level. The margin of error for respondents ages 16 to 25 is plus or minus 4.6 percentage points, and the margin of error for respondents ages 26 and older is plus or minus 4.8 percentage points.

Interviews were conducted for the Pew Hispanic Center by Social Science Research Solutions (SSRS).

A Note on Terminology

The terms “Latino” and “Hispanic” are used interchangeably in this report.

The term “youths” refers to 16- to 25-year olds unless otherwise indicated. In this report, the terms “Latino youths,” “young Latinos” and “young adults” are used interchangeably.

All references to whites, blacks, Asians and others are to the non-Hispanic components of those populations.

“Foreign born” refers to persons born outside of the United States to parents neither of whom was a U.S. citizen. Foreign born also refers to those born in Puerto Rico. Although individuals born in Puerto Rico are U.S. citizens by birth, they are included among the foreign born because they are born into a Spanish-dominant culture and because on many points their attitudes, views and beliefs are much closer to Hispanics born abroad than to Latinos born in the 50 states or the District of Columbia, even those who identify themselves as being of Puerto Rican origin.

“Native born” or “U.S. born” refers to persons born in the United States and those born abroad to parents at least one of whom was a U.S. citizen.

Unless otherwise noted, this report uses the following definitions of the first, second, and third and higher generations:

First generation: Same as foreign born above. The terms “foreign born,” “first generation” and “immigrant” are used interchangeably in this report.

Second generation: Born in the United States, with at least one first-generation parent.

Third and higher generation: Born in the United States, with both parents born in the United States. This report uses the term “third generation” as shorthand for “third and higher generation.”

Language dominance is a composite measure based on self-described assessments of speaking and reading abilities. Spanish-dominant persons are more proficient in Spanish than in English, i.e., they speak and read Spanish “very well” or “pretty well” but rate their English speaking and reading ability lower. Bilingual refers to persons who are proficient in both English and Spanish. English-dominant persons are more proficient in English than in Spanish.

Recommended Citation

Pew Hispanic Center. “Between Two Worlds: How Young Latinos Come of Age in America,” Washington, D.C. (December 11, 2009).

About the Focus Groups

The Pew Hispanic Center conducted seven focus groups during the summer of 2009 to help inform the development of the survey questionnaire and to ask young Latinos about the issues that are important to them. Mark Hugo Lopez, Cristina Mercado, Ana González-Barrera and Jennifer Medina moderated the focus groups. Focus groups were held in Los Angeles; San Jose, Calif.; Chicago; Orange, N.J.; Silver Spring, Md.; Langley Park, Md.; and the District of Columbia. Diego Uriburu of Identity Inc. of Gaithersburg, Md., helped to organize the Silver Spring and Langley Park focus groups, and the Congressional Hispanic Caucus helped to organize the one in Washington, D.C. All groups were composed of Latinos between the ages of 16 and 25. Focus group participants were told that what they said might be quoted in the report, but we promised not to identify them by name. The quotations interspersed throughout the report are drawn from these groups.