As the new nexus of teens’ online experience, online social networks are the focus of widespread concern over the disclosure of personal information online.

Over the course of seven years, our research examining teenagers’ use of the internet has repeatedly shown that teens are one of the most wired segments of the American population. And teenagers, perhaps more than any other age group in the U.S., have been well-positioned to take advantage of new communications technologies and social media applications as they emerge.

Psychologists have long noted that the teenage years are host to a tumultuous period of identity formation and role development.2 Adolescents are intensely focused on social life during this time, and consequently have been eager and early adopters of internet applications that help them engage with their peers. In our first national survey of teenagers’ internet use in 2000, we found that teens had embraced instant messaging and other online tools to play with and manage their online identities. In our second major study of teens in 2004, we noted that teenagers had taken to blogging and a wide array of content creation activities at a much higher rate than adults. Teens who adopted these tools were no longer only communicating with text, but they were also developing a fluency in expressing themselves through multiple types of digital media – including photos, music and video.

And along comes MySpace….

MySpace was by no means the first social networking application to come to the fore, but it has been the fastest-growing, and now consistently draws more traffic than almost any other website on the internet. It has also garnered the majority of public attention paid to online social networking, and sparked widespread concern among parents and lawmakers about the safety of teens who post information about themselves on the site.

Social networking sites appeal to teens, in part, because they encompass so many of the online tools and entertainment activities that teens know and love. They provide a centralized control center to access real-time and asynchronous communication features, blogging tools, photo, music and video sharing features, and the ability to post original creative work – all linked to a unique profile that can be customized and updated on a regular basis. However, in order to reap the benefits of socializing and making new friends, teens often disclose information about themselves that would normally be part of a gradual “getting-to-know-you” process offline (name, school, personal interests, etc.). On social network sites, this kind of information is now posted online — sometimes in full public view. In some cases, this information is innocuous or fake. But in other cases, disclosure reaches a level that is troubling for parents and those concerned about the safety of online teens.

Social networking sites are by no means the first online application to spark worries among parents. In our first study of teen internet usage in 2000, well before social networking sites emerged, we reported that 57% of parents were worried that strangers would contact their children online. At that time, close to 60% of teens had received an instant message or email from a stranger and 50% of teens who were using online communication tools said they had exchanged emails or instant messages with someone they had never met in person. At the time, parents responded to these worries by taking precautions such as monitoring their child’s internet use and placing the computer in a public area of the home — much as they do today.

Studies of child victimization have shown that incidences of sexual abuse, physical abuse and other forms of maltreatment have been declining since the early 1990’s.3 Research has also shown that acquaintances and family members are responsible for most of the physical crimes committed against children.4 However, the type of “friending” activity that occurs on social networking sites, where users link to one another’s profiles to grow their networks, highlights the radically changing notion of what it means to be acquainted with someone. It is so compelling to some teens to display big friendship networks and so easy with a click or two to establish online connections that it is possible for teens to have virtual ties to others on social networks whom they have never met in person. That raises key questions and concerns: Are these people they have some connection to—through online or offline friends who can vouch for them? What kind of information are they posting to their profiles, and who has access to that information?

When asked these questions, teens consistently say that the decisions they make about disclosing personal information on social networks and in offline situations depend heavily on the context of that exchange. Posting a generic school name to a profile like “Jefferson High” does not reveal the same level of specificity as posting “Our Lady of Perpetual Help School.” Likewise, those who live in smaller towns who disclose the name of the city where they live would share more detail than those who say they live in a large metropolitan area. Many of the teens we interviewed were aware of these distinctions and most are taking steps to restrict public access to their profiles.

This study was conducted in two parts; first we conducted a series of six focus groups with middle and high school students in two American cities in June of 2006. Groups were single gender, and grouped in three grade ranges – 7th and 8th, 9th and 10th, and 11th and 12th grades. After completing the six in-person focus groups, a 7th online, mixed gender high school-age focus group was also conducted. These qualitative results are not representative of the U.S. teen population.

Second we fielded a nationally-representative call back telephone survey of 935 parent–teen pairs. We interviewed teens who were between the ages of 12 and 17. This survey was fielded between October 23, 2006 and November 19, 2006 and has an overall margin of error of plus or minus three percentage points.5

American teenagers continue to lead the trend towards ubiquitous internet connectivity in the U.S.

Looking at a general picture of teen internet adoption, American teens are more wired now than ever before. According to our latest survey, 93% of all Americans between 12 and 17 years old use the internet. In 2004, 87% were internet users, and in 2000, 73% of teens went online.

While teens go online in greater numbers and more frequently than in the past, usage gaps between teens of different socio-economic status persist. Teens whose parents are less educated and have lower incomes are less likely to be online than teens with more affluent and well-educated parents. Of teens whose parents have college educations, 98% are online while only 82% of teens whose parents have less than a high school education are online. In general, income and parental education levels have a greater impact than race and ethnicity on the frequency of internet use.

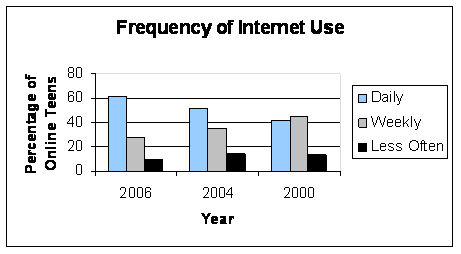

Not only are more teens online, but they are also using the internet more intensely now than in the past. Eighty-nine percent of online teens use the internet at least once a week. The percentage of online teens who report using the internet daily has increased from 42% in 2000 and 51% in 2004 to 61% in 2006. Of the 61% of teens who report using the internet daily in 2006, 34% use the internet multiple times a day and 27% use the internet once a day. If teens log onto the internet daily, they are more likely to log on multiple times rather than once per day.

Home continues to be the primary location where teens access the internet. However, there are still notable numbers of teens, especially those in lower income or single parent households, who report using the internet most often from school, the library, or a friend or relative’s house.

More and more teens have broadband connections at home. Three-quarters of all online teens live in households with broadband internet access, up from 50% of online teens with broadband in 2004. Just a quarter of online teens have dial-up internet access at home.

As we found in 2004, teens who have active lives offline are also active online. For instance, teens who are involved in after school activities such as sports, band, drama club, or church go online with greater frequency than teens who have fewer extracurricular commitments.

Many parents take online safety precautions with their teenage children.

To understand fully how teens use the internet and in particular social networking websites, it is important to explore the circumstances of their home internet use – where the computer is located, what kinds of protective software are used, and what kind of rules a parent has in the household around use of the internet and other media. This helps to add context to generalized parental worries about teen internet use. We looked at both technical and non-technical methods that parents use.

More than half of parents with online teens have a filter installed on their computer at home.

[AGE]

Teens are generally aware that there are filters on their home computers. Half (50%) of all online teens who go online from home say that the computer they use at home has a filter that keeps them from going to certain websites. A bit more than a third of teens (37%) say that their home computer is not filtered, and another 13% say they do not know if the computer has a filter or not.

Teens have a reasonably accurate understanding of whether or not their home computer (according to their parent or guardian) has a filter installed on it. One-third or 34% of online teens were correct that their parents had installed a filter on their home computer. Another 18% of online teens agreed with their parents when they stated that they did not have filters on their home computer. However, in some families there are contradictions between what the parents say and what their children say. Nearly 13% of teens said that they did not have filters on their home computers, while their parents stated that they did. And another 12% believed that they had filters on their computer at home, when their parents said a filter was not in use.

Some teens simply professed uncertainty and said they did not know if they had filters at home. Overall 6% of online teens were uncertain and actually had filters at home, with another 6% of online teens unsure and living in homes without filters.

Monitoring software is not as popular as filters, but is still used by 45% of parents with online teens.

The other broad category of technical protection for online teens is monitoring software – these are programs that run on the family computer and record where a child goes, what he or she does, and in some cases, record every key stroke that a child makes. A bit under half (45%) of parents of online teens say that they have monitoring software installed on the computer that the teen uses at home. About 4 in 10 (38%) parents say they do not have monitoring software installed and another 14% say they are not sure.

Teens are also relatively aware of monitoring software on their home computers, though less aware than they are of filtering. About a third of teens (35%) with internet access at home believe that there is monitoring software on their home computer, and about half (48%) say there is not any monitoring software installed. About 1 in 6 (17%) say they are not sure whether or not there is monitoring software on the computer they use at home.

Teens are a bit less accurate than they were with filters when it comes to assessing whether or not there is monitoring software on their home computer. Overall, 22% of teens correctly indicated that they have monitoring software on their home computer. Another 22% correctly indicated that they do not have monitoring software at home. Some 18% of teens incorrectly believed that they did not have monitoring software on their home machine when according to their parents they did, and another 10% believed there was monitoring software on their computer when there was not. And as with filters, a significant number of teens said they did not know whether or not they had monitoring software installed – 7% of online teens are uncertain and do actually have monitoring software installed according to their parents and another 6% of online teens are unsure and did not have the software installed on the computer they used at home.

Many filtering packages warn users when the software is blocking content, while monitoring packages often work silently in the background. Users of computers with filters may be more aware that such a tool is installed because of the operational characteristics of the software.

Technical protective measures are used most often in households with younger teens.

More of these technical protection and monitoring tools are used in households with younger children. Fully 58% of families with teens ages 12-14 have filters installed compared with 47% of homes with older teens, and 51% of households with younger teens say they use monitoring software, compared with 39% of households with teens ages 15-17. Monitoring software seems to be used most in homes with younger teen boys, while filters are used in the homes of younger teens regardless of gender. Parents who have a more positive view of technology in their lives and those who own more types of personal technology (cell phones, PDAs) are more likely to use monitoring software on the computer their child uses at home.

Parents also employ a wide array of non-technical protections and behaviors to protect their teens.

On the non-technical side, parents have a variety of techniques at their disposal. Parents can check the computer to see where a teen has gone online and what they have done. They can also place the computer in a well-traveled area of the home. Parents can establish family computer and internet use rules, including what websites may or may not be visited, what types of personal information may be shared online with others and how much time a child may spend online.

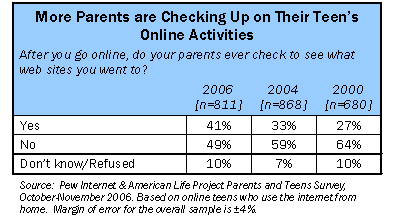

Teens today are more aware that their parents are watching them online.

[1]

Another late high school-aged girl explains the relationship between monitoring and trust established in her family. “My parents sometimes monitor where I go, but they pretty much trust me when I’m online. I spend about 3 hours a day online, including time at work. They have talked to me about being careful what sites I visit.”

Teens in the other, less-monitored third of online teens, explain how knowledge imbalance affects oversight in the home. Says one tech-savvy high school boy, “I’m pretty sure they’d be upset if they saw me browsing hate sites, or looking at animal porn, but my internet usage isn’t very well moderated. No, they don’t talk to me about it, simply because it’s probable that I know more about it than them.”

Three years ago, we found that 33% of teens believed that their parents were checking up on their online behavior after they went online, while 41% of today’s teens believe that their parents monitor them after they’ve gone online. Parents are most likely to report checking up on younger teens (ages 12-14), in particular younger girls. Seven in ten parents of younger teens checked up on their online behaviors, compared with 61% of parents of older teens.

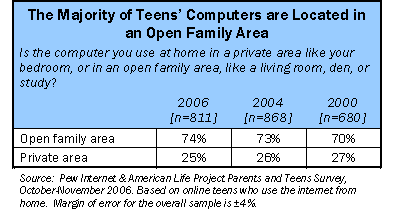

Three-quarters of home computers are in a public place in the home.

Teens report that the computer that they use at home is generally found in a public area in the home, like a living room, den or study. Three-quarters of teens who go online at home say the computer is in an open family area. Another quarter (25%) say it is in a private space in the home, like a bedroom. And one percent say they have a laptop which can be moved and used in a variety of places both public and private. These numbers are remarkably similar to the findings in our 2004 and 2000 surveys, where 73% of teens and 70% of teens, respectively, reported that their computer was in a public location in the home.

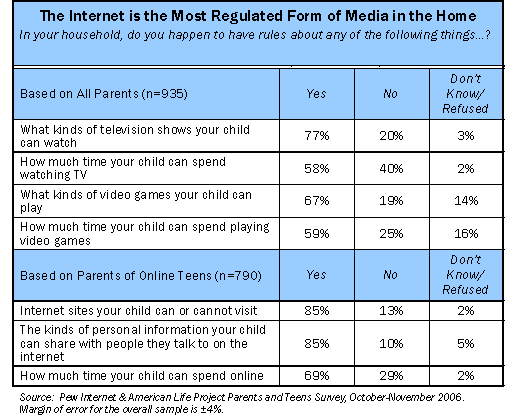

More households have rules about internet use than for other media.

Parents are also particularly likely to establish rules about their children’s internet wanderings and information sharing. More than eight in ten parents (85%) of online teens said that they had rules about internet sites their child could or could not visit, and a similar number (85%) said they had established rules about the kinds of personal information their child could share with people they talk to on the internet. Fewer parents (69%) said they had household rules for how long a teen could spend online. One high school-age boy detailed his internet restrictions at home. “My parents limit my time on the internet. I can only spend about 1-2 hours of non-school work time on it. They try checking up on me but I can get away with a lot if I wanted. They make sure to tell me never to meet people on it because people pretend to be someone they are not.”

Still, most teens focused on household internet time limits when talking about restrictions on their internet use in our focus groups. “My parents don’t really have any rules directed to the internet,” one young high school age women told us. “I know better [than] to go to dirty sites and stuff. The only rules I have is that I have 2 hours a day on the computer, and I can’t be on the computer after 10 pm. I tend to bend the 2 hours rule quite often.” While rules about what kinds of sites teens could visit and length of time they can spend online do not vary by age or sex, most of the rules about the sharing of personal information are implemented (or are reported to be so) by parents of girls and older teens.

Nevertheless, in comparison to other types of media with in the home, the internet is a much more regulated piece of technology than the television or video game console.

Younger boys are the most likely to have gaming rules applied to them.

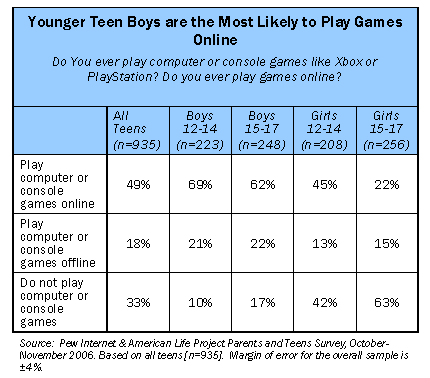

Nearly two-thirds of parents of online teens (65%) say they have household rules about the types of video games their child can play, and 58% of those same parents said they had rules about the amount of time their teen could spend playing video games.

Much of the regulation of gaming is aimed at the most avid game-players – younger boys. Parents of younger boys were more likely than other groups of parents to say they had rules about what kind of games could be played and for how long. It is also important to note that fewer teens play games than go online, which may be reflected in the lower percentage of parents with rules about games.

Regulation of television watching habits is mainly aimed at younger teens.

Three quarters (75%) of parents of online teens regulate what kinds of television shows their child watches, and 57% of parents of kids who go online say that they have rules about how much time their child can spend watching TV. Regulation of television watching habits is primarily aimed at younger teens, with parents of these teens more likely to report having these rules than parents of older teens.

Despite all the rules parents impose on internet use, parents still think that the internet is a good thing for their child.

Overall, 59% of parents of online teens say that the internet is a positive addition to their children’s lives. Still, the percentage of parents who think that the internet is good for their children has decreased a statistically significant amount from 67% in 2004 to 59% in 2006. However, that does not mean that more parents today are more “anti-internet” than they were two years ago. Instead, more parents have become ambivalent; in 2006, 30% said that they did not think that the internet had an effect on their children one way or the other, compared with 25% who reported this in 2004.