Parental and institutional regulation of teens’ mobile phone use.

As cell phones become increasingly ubiquitous in the backpacks and back pockets of American teens, parents and schools struggle with how to manage teens’ constant connectivity to friends, networks and the information that these devices allow.

Teens in our focus groups talked about how in many families, parents as much as teens were the instigators of the first phone purchase. Parents are most often the phone provider – 70% of teens have phones fully paid for by someone else. Most American teenagers get their first cell phone in middle school, at age 12 or 13: 23% of teens got their first cell phone at age 12 and another 23% got their first phone at age 13. About 20% of teens have their first phone by the time they enter middle school (age 11 or under for first cell phone owned). Another 14% of teens get their first phone at age 14 and roughly 20% get their first phone when they’re between 15 and 17.

Teens from lower income households generally must wait a little longer to get their first cell phone. A greater proportion of teens from lower income households – earning less than $30,000 annually — got their cell phones at later ages, with 18% getting their first cell phone at age 16, compared with just 6% of teens from wealthier homes. The trend persists through various income brackets, with teens more likely to get their phones at earlier ages in higher income households.

[T]

Parents and limits on cell phone use.

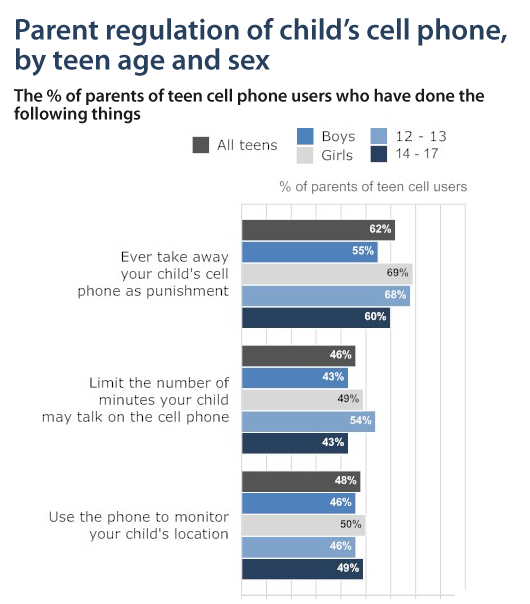

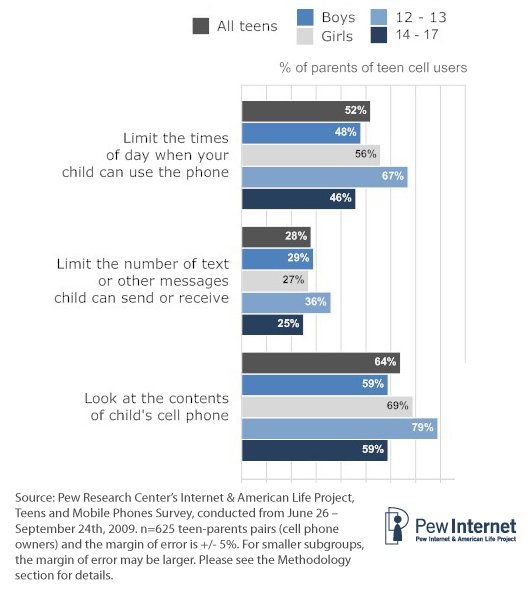

Although parents often facilitate the initial purchase of a mobile phone, they seldom obtain a phone for their teen and then step out of the picture. Phones are regulated by parents and used as parenting tools. Parents often place limits on the times of day their teen can use his or her phone, as well as the numbers of minutes they can use or texts they may send. Parents look at the contents of their teen’s phone, use the phone to monitor their child’s location and take the phone away as punishment.

[at school]

About half of parents (52%) say they have set limits on the times of day when their child can use the phone and a similar number (48%) say that they use the cell phone to monitor their teen’s location.41 A middle school boy describes his mother’s limits on his phone use: “Yeah my mom set it so it will get deactivated at eleven on school nights. So when I’m going to sleep I’ll keep getting texts and I’ll be like, ‘I’m going to bed,’ and people will be like, ‘What?’”

One high school boy narrates some of the conflict between him and his mother over location monitoring. “Yeah, she’s like, ‘The reason why I got you a cell phone is that you can call me when you get home or when you get to this place,’ and if I don’t call she like flips. ‘Why do you have a cell phone if you can’t call me?’ Like, ‘I got caught up.’ She’ll be like, ‘No, no excuses.’ So, having the cell phone is a pro and con.”

Parents also limit the number of minutes their child may talk on the phone – 46% of parents report setting these types of limits, possibly in response to the fact that many family plans – used by 69% of teens – have a set number of minutes shared across the family. “It’s all about the minutes. Because I don’t know, my mom and dad, I go over my minutes sometimes, and they started yelling at me or something, they said pay for this, stuff like that,” said one high school-age boy.

Parents are least likely to report limiting the number of text messages or other messages their child sends or receives on their phone – a bit more than a quarter (28%) of parents say they set text message limits. Most teens have unlimited text messaging plans, which for many families may make these limits unnecessary.

The flip side of parental regulation and monitoring is that teens report feeling suffocated by the constant contact with parents. “The worst thing is, I guess, like, when you don’t want to get in touch with your mom, but she can always get in touch with you,” said one younger high school girl. “Sometimes you want your space. But when you have your phone you can’t have your space.”

Girls, particularly younger girls, are much more likely to be the object of parental regulation around the cell phone than boys or older teens. Girls are more likely to have parents looking at the contents of their cell phones, have limits on the times of day they can use the phone and are more likely than boys to have their cell phone taken away as punishment for misdeeds.

Nearly 7 in 10 girls (69%) have parents who say they have taken the phone away as punishment. A similar percentage (69%) of parents of girls report looking at the contents of their daughter’s phone, compared with 55% and 59% of boys’ parents, respectively. Fully 56% of parents of girls say they limit the times of day when their daughter can use her cell phone compared with 48% of boys’ parents. Parents of girls and boys are just as likely to engage in other monitoring behaviors like limiting the number of minutes a teen may talk, limiting the number texts a teen may send or monitoring his or her location via the phone.

A teen’s age is also a significant factor in whether or not a parent reports regulating his or her phone. Younger teens, particularly younger teen girls, are the primary targets of parental phone regulation. Teens 12 to 14 are the primary focus of parent regulation that involves looking at the content of the teen’s phone – between 72% and 80% of teens in this age range have parents who say they look through their child’s phone. The 12-to-14 age range is also the age when parents are most likely to limit text messaging — 35% of parents of teens with cell phones in this age range report doing this, compared with 23% of parents of older teens. Teens 12 to 15 years old are the primary recipients of limits around the times of day they may use their cell phone. Some 60% of parents of 12-to-15 year-olds report limiting the times of day when their teen’s phone may be used, as do 39% of parents of 16-17 year-olds.

Teens ages 13-14 are more likely to have parents who report limiting the number of minutes they may talk on the phone and are the age group most likely to have parents who say they’ve taken their child’s phone away as punishment. Parents of younger girls ages 12-13 are the most likely to report engaging in multiple forms of regulation of their daughter’s cell phone. These parents are more likely than parents of sons or of older teens to say they’ve limited the number of minutes their daughter may talk on the phone. They are also more likely to report going through the contents of their child’s cell phone, taking away her phone as punishment and limiting the number of text messages she may receive than parents of other teens.

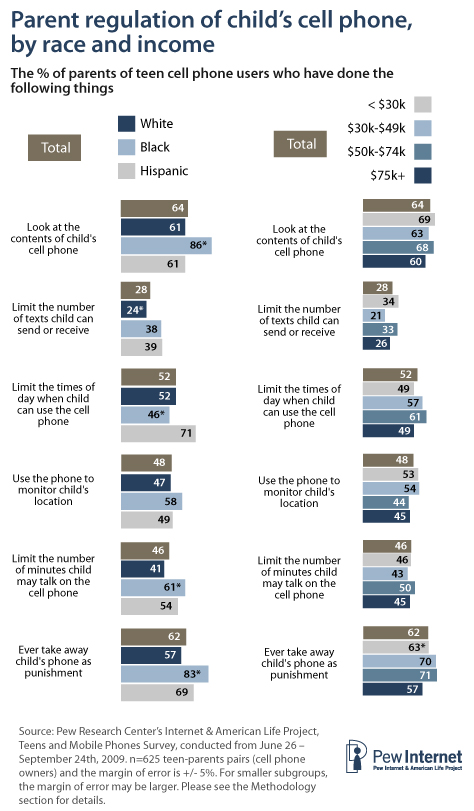

African-American parents are more likely to report regulating their child’s cell phone than white parents. African American parents are more likely than white parents to look at the contents of their child’s cell phone, take the phone away as punishment, limit the times of day their teen may use the phone, and limit the number of minutes or text messages their child may send, receive or use.

Parents are more likely to report limiting the number of minutes their child can talk if their child does not send or receive text messages. Six in 10 parents of non-texters limit the number of minutes their teen can talk on the mobile phone compared with 44% of parents of texting teens.

A small number of teens report that their parents monitor their location through their cell phone. A bit more than one in six teens (17%) say that their parents have monitored where they were through the cell phone. A little less than half (48%) of parents report monitoring their teen’s location through the cell phone. Not surprisingly, teens see this as an unwelcome intrusion into their lives. One participant in the focus groups had a monitoring service enabled on her phone and was very curt in her feelings toward it. Younger teens, particularly girls, are the most likely to report parental monitoring of their location. Among 12-13 year-olds, 25% report having their whereabouts monitored by their parents through their phone compared with 14% of older teens. As with other forms of control, younger girls are the most likely to report location monitoring through their cell phones, with one-third (33%) saying their parents engage in this behavior, more so than all older teens and younger boys. There is no difference in teen-reported monitoring by race or socio-economic status.

About 10% of teens and parents both acknowledge that the parent is monitoring the teen’s location with the phone. Another third (37%) of teens have parents who say they monitor their whereabouts with the phone, but the teens themselves are not aware of such surveillance. On the flip side, there is another small group of teens (7%) who report being monitored via their cell phone, but whose parents do not report such monitoring behavior. Finally, the remaining 43% of parent-teen pairs represent cases where both parties say there is no monitoring of the teen’s whereabouts with his or her mobile phone.

Cell phone plans and parental regulation of the phone.

The type of plan teens have for their phone – unlimited or limited minutes, unlimited or limited texting and whether they’re on a family, pre-paid or separate plan are closely linked with parental regulation. Parents are more likely to place limits on their child’s text messaging when their teen has a family or pre-paid cell phone plan; or when their child’s cell phone plan limits the number of texts they may send per month; or when they must pay per text message. Similarly, teens on cell phone plans that limit the number of minutes they may talk (or the number of texts they may send) are more likely to have parents who say they place restrictions on the number of voice minutes their child may use.

Teens with unlimited text messaging plans (75% of all teens with cell phones) are more likely to have parents who say they take their teen’s phone away as punishment and that they limit the times of day when their child can use their mobile phone. However, if we look at reported behavior, teens who say they text message their parents most often are more likely to have parents who say they do not regulate their child’s mobile phone in any way. This may well indicate a rapport between generations that builds on mutual trust.

Few parental actions relate to differences in negative cell phone uses by teens.

Whenever interventions, whether formal and not, are evaluated, the ultimate question becomes – do they work or not? While this report cannot show causality or prove that certain interventions do or do not work, we can report on the relationship between particular steps that parents take to regulate their child’s mobile phone and the behaviors of teens themselves. Generally speaking, there is relatively little correlation between parental interventions on cell phone use and behavioral outcomes on the part of teens.

Compared with teens whose parents place no time-based limits on their cell phone use, teens whose parents limit when they may use the phone are less likely to say they text (27% vs. 42%) or talk (44% vs. 57%) while driving. On the other hand, these teens are more likely to report experiencing harassment through the phone. Teens with parents who limit when they can use the phone are also more likely to have received “sexts” or text messages with sexually suggestive images of peers attached. However, this kind of regulation shows no relationship with riding with drivers who text or use the phone dangerously behind the wheel or with sending sexually suggestive images of oneself to others with your phone. As noted above, these relationships do not suggest causality. Parental limitations may, for example, be implemented after they have discovered distressing material on their teen’s phone or otherwise in response to some negative cell phone related incident, rather than as a preemptive move.

Teens who have parents that monitor their location using the cell phone are generally not aware that their parents are monitoring them – 17% say their parents monitor their location with the phone, compared with 48% of parents who say they monitor their child’s location. There is also a relationship between parents who monitor their child’s whereabouts with the phone and teens reporting harassment through their phone – a larger percentage (30%) of teens with monitoring parents report harassment through the phone compared with 22% of teens whose parents do not monitor their location with the phone. Of course it may be that a teen who experiences harassment triggers a greater level of monitoring in parents.

Limiting the number of minutes a child may talk on the cell phone does not measurably relate to any talking- or texting-related negative behaviors. However, limiting the number of text messages a child may send does seem to be related to lower levels of some worrisome text-related behaviors. Teens whose parents limit their texting are less likely to say that they have been in the car while the driver texted or used the phone in a dangerous manner. These teens are also less likely to say they have sent text messages they later regretted, or to say that they have sent a sexually suggestive image of themselves to someone via text. Limiting texts is not associated with a lower likelihood of driving-age teens texting behind the wheel, nor does it reduce the likelihood that a teen receives cell phone spam or is harassed through his or her phone.

While nearly two-thirds of parents say they’ve taken their child’s phone away as punishment, many of these teens have a greater likelihood of reporting certain behaviors or feelings than teens whose parents do not use this tactic. Teens whose parents have taken away their phone are more likely to report being harassed through their phone (30% vs. 20%), regretting a text they sent (53% vs. 39%), and being in a car when the driver used the phone in dangerous way (48% vs. 33%). It may be that parents of teens are resorting to taking the phone away because their child is engaged in more risky behaviors, rather than indicating that taking away the phone is an ineffective punishment.

Mobile phones and schools.

As institutions that are often called upon to serve in loco parentis, schools take a variety of approaches towards the regulation of the mobile phone within their four walls and on their campuses.

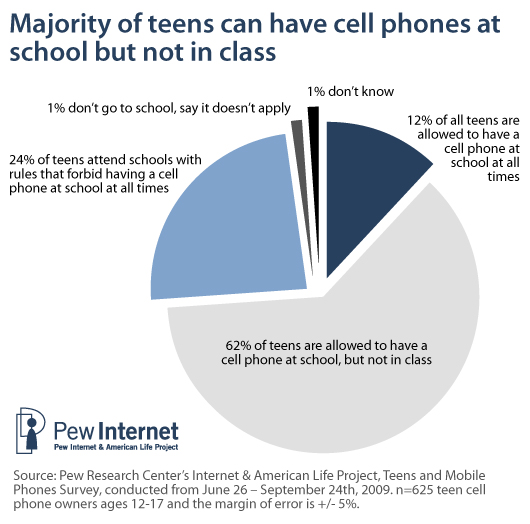

When it comes to possession of a mobile phone during the school day, just 12% of teens with cell phones say that they can have a cell phone at their school at all times. A majority of teens (62%) say that they can have a cell phone at school but not in class, and another quarter of teens (24%) attend schools that forbid cell phones altogether.

Our focus group conversations support these findings and suggest that most schools treat phones as a disruptive force to be kept turned off and away from the classroom. Many teens talked about a tiered system based on a “if they can see it, they can take it” philosophy. An older high school girl describes a common system: “Yeah, it’s happened to me three times. The first time they take it for a day. They take it for a night and you don’t see it until the end of the next day of school. The second time they take it for a week, and the third time the rest of the semester.” Other teens describe systems in schools that require parents to come to the school to retrieve the phones of wayward students.

Some schools allow limited use of cell phones, as this older high school girl explains, “At ours, you can have it in passing periods and lunch. And if they see it, it gets taken and I think the first time you go back at the end of the day and get it.”

Some teens describe what feels like arbitrary enforcement or a lack of clarity around school rules for mobile phones. “I don’t text much in school. And we don’t really have, and our rules are just like whatever the teachers feels like,” said one younger high school-age boy. “Some teachers give it to you at the end of the day, some after class, some keep it over the weekend if it’s like, Thursday or Friday.” Others described schools “giving seniors leeway” with phones and teachers playing favorites or looking the other way around cell phone enforcement. Said one middle school girl, “At my school, it’s kind of messed up, but if you’re one of the favorites, and I’m one of the favorites with some of my teachers, they just let you use your phone.”

A younger high school-age girl describes one teacher’s classroom policy: “Well, my teacher has a mind of her own, so she takes up the phones in class before class starts and then at the end she’ll give them back and then that’s not like the school policy. That’s just her policy, but if you don’t turn it in and it goes off, then it gets sent to the principal and your parents have to come pick it up.” Another high school-age girl describes a creative teacher, who, “if she caught you texting, she’d pick up your phone in class and read the message.” This is apparently an effective deterrent according to reports of teens in our focus groups.

Other teens report that their teachers use their own phones in class: “Well, it says in the book that you’re not supposed to have it, like if you have it, it’s supposed to be off and in your book bag or whatever, but like it’s extremely flexible. Like, some of my teachers even use their phone in class, so you can use it as long as it doesn’t make noise.”

A few schools simply ban phones altogether: “We have absolutely no cell phones,” said one older high school girl. “If you’re on school grounds, you can’t even use it in your car.”

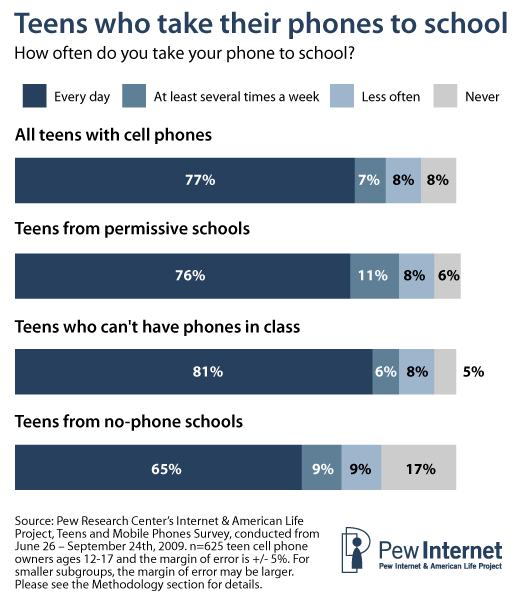

Despite these restrictions, teens are still overwhelmingly taking their phones to school – 77% take their phones with them to school every school day and another 7% take their phone to school at least several times a week. Less than 10% of teens take their phone to school less often and just 8% say they never take their phone to school.

While a higher percentage of teens who attend schools that forbid all cell phones say they never bring their phone to school (17% vs. 5% at other schools), nearly 65% of teens at “no phone” schools bring their cell phone to school every day, anyway. Four in five (81%) teens at schools where they may have a cell phone, just not in class, bring their phone to school everyday.

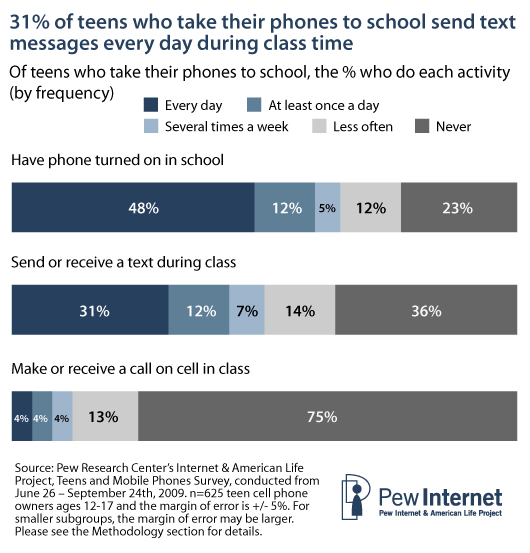

Further, many teens who take their phones to school are keeping them on and using them during the school day, sometimes during instructional time. Six in ten teens (60%) say they have their phone turned on at school at least once a day and sometimes several times a day. Just one-quarter of teens (23%) who take their phones to school say they never have them turned on during the school day.

Teens with carte blanche to have their phone with them at school are just as likely as teens who can have the phone, just not in class, to have their phone on several times during the school day. Some 49% of both groups report such behavior. Teens who are not allowed to have a phone at school are more likely to say they keep the phone off during the school day, with one-third (32%) saying they never turn their phones on, compared with 21% of teens who can have phones at school but not in class, and 16% of teens who have fewer restrictions.

More striking is the two-thirds of teens (64%) who tote their phones to school who say they have ever sent or received a text message during class. Nearly one-third (31%) of teens who take their phones to school text in class several times a day and another 12% of those teens say they text in class at least once a day. Fewer teens report that they place calls during class, though 4% manage to make calls from class several times a day and another 4% do so at least once a day. Fully 75% of teens who bring their phones to school say they never make calls during class time.

One middle school boy describes texting in class at his school: “When I’m in class, I just see people pull out their phone and try to be sneaky, and get past the teachers and try texting and stuff. Like, one time I tried that and my teacher caught me.”

[a second phone]

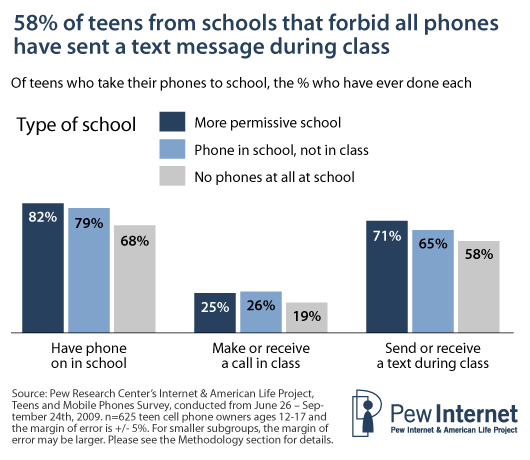

In-class texting varies little with regard to the aggressiveness of a school’s regulation of its students’ mobile phones – teens with full access to cell phones are just a bit more likely (71% to 58%) to say they send or receive texts in class than teens who attend schools that forbid phones altogether. Perhaps heartening to administrators is the finding that about a third of teens text frequently in class (31%), another third of teens (33%) text in class occasionally and a third (36%) say they never send text messages during class. These findings mostly hold regardless of the regulatory environment, although there are exceptions in the extremes of behavior. Teens in schools where phones are totally forbidden are slightly less likely to text in class several times a day, and are more likely to say they never text, than are teens who attend schools that allow cell phones at all times.

Roughly 25% of teens take their cell phones to school and say they have made a phone call on their cell phone during class, although most do so only infrequently. The data show that 13% of teens who bring their cell phones to school make a cell call during class less often than once a week and just 4% make such calls several times a week. Another 4% say they make calls at least once a day and yet another 4% say they make calls several times a day during class. There are few statistically significant differences on this question by school regulatory environment.

Girls and older teens are more likely than boys and younger teens to take their cell phones to school every day. Teens from lower income families are more likely to say that they make calls during class time several times a day, with 12% of teens whose parents earn less than $30,000 annually saying they make calls that frequently compared with just 2% of teens from wealthier families.

Cheating with cell phones.

Another problem associated with cell phones in school is that the technology offers new opportunities for cheating. Although this report does not have survey data to establish the prevalence of this problem, responses from the focus groups indicate it is not uncommon. Most of the teens in the sessions said that they have heard that other students have used cell phones to cheat, and some admitted to doing it themselves. Themes from their focus group responses indicate that cheating is carried out through the cell phone by texting test answers to others, taking pictures of exams, taking pictures of textbook materials to bring into an exam, and getting answers online, especially through Web sites that claim they will answer any question. A high school girl commented, “I have heard of people taking pictures of the textbook — a section where they didn’t know anything – and then they’ll zoom in and take a photo. It’s kind of like a sheet of notes, but it is on your phone. It’s not like you have to pull out a piece of paper and unfold it and make a lot of noise. It is easier.” A high school boy stated, “I’ve seen a lot of kids with their iPhones … They’ll Google something like an essay question or something like that. “

In addition, several teens mentioned that their phone is their calculator, which can also be a method for cheating when calculators are not allowed during math exams. A high school girl recalled, “Last year I would use the calculator and pretend I was writing my work down. Then I would use my calculator in order to get this algebra problem. Teachers will be like, ‘Oh yeah, you passed this class,’ and I’m like, ‘Calculator,’ in my head.”