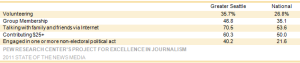

Americans’ views on the appropriateness of changing a baby’s genetic characteristics depend in large part on the intended purpose and on whether or not human embryos would be used in testing these techniques. A majority of Americans support the idea of using gene editing with the goal of delivering direct health benefits for babies, but at the same time, a majority considers the use of such techniques to boost a baby’s intelligence something that takes technology “too far.”

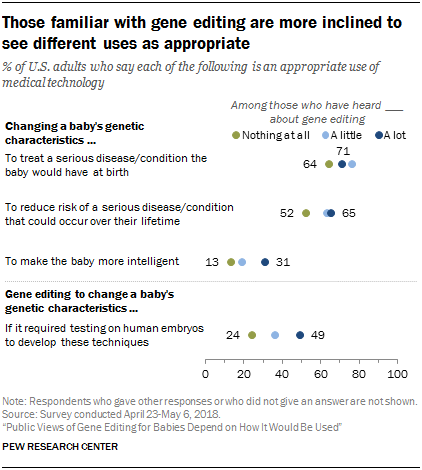

About seven-in-ten Americans (72%) say that changing an unborn baby’s genetic characteristics to treat a serious disease or condition that the baby would have at birth is an appropriate use of medical technology, while 27% say this would be taking technology too far. A somewhat smaller share of Americans say gene editing to reduce a baby’s risk of developing a serious disease or condition over their lifetime is appropriate (60% say this, while 38% say it would be taking medical technology too far). But just 19% of Americans say it would be appropriate to use gene editing to make a baby more intelligent; eight-in-ten (80%) say this would be taking medical technology too far.

These are some of the findings from a new Pew Research Center survey conducted April 23-May 6, 2018, among 2,537 U.S. adults.

While public discussions about potentially altering a baby’s genetic makeup have been ongoing for decades, the development of a new gene-splicing technology – known as CRISPR – has accelerated the debate and brought new urgency to better understanding public opinion about gene editing as well as the broader social, ethical and policy implications ahead.1

Previous Pew Research Center surveys have tracked public opinion about gene editing using different question wording and, in some cases, different polling methodologies. As such, those findings are not directly comparable to this new survey. However, the broad pattern – that public support for gene editing varies with its intended purpose – is consistent with a 2016 study that explored public views about the possibility of using gene editing to “enhance” a baby’s health over the course of their lifetime and a 2014 survey.2

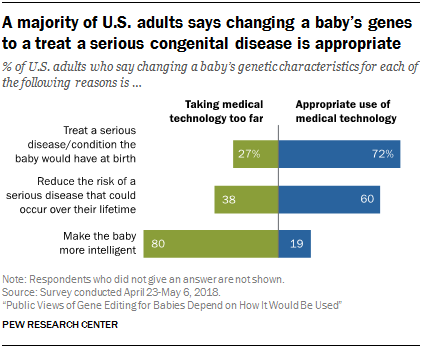

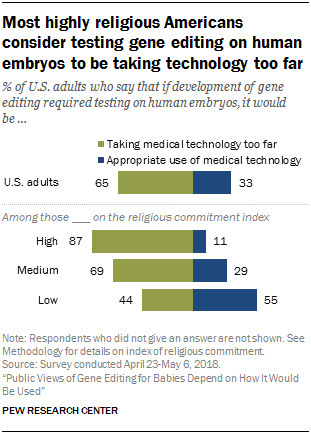

Regardless of the intended purpose of gene editing, experts acknowledge that further development of these techniques will likely involve testing in human embryos. In August 2017, research scientists in the United States reported the first successful use of gene editing in human embryos to eliminate an inherited condition. When asked to consider the possibility that the development of gene editing would involve testing on human embryos, one third of Americans (33%) say this would be appropriate while about two-thirds (65%) say this would be taking medical technology too far.

The 2016 Pew Research Center survey using different question wording found that most adults said testing on human embryos to develop gene editing would make gene editing less acceptable for them.

Public views of gene editing vary by religious commitment, gender, levels of science knowledge and familiarity with gene editing

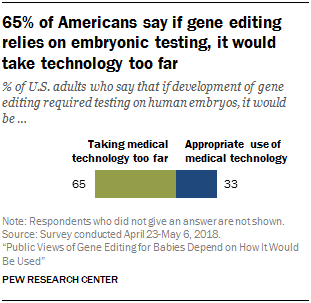

Several patterns emerge in public opinion about gene editing in these varying contexts. There are large differences in acceptance of gene editing between the highly religious and less religious. In addition, there is a gender gap in views about gene editing, with women less accepting of it than men. People with higher levels of science knowledge and greater familiarity with gene editing also tend to be more accepting of it.

Religious Americans are more likely to view gene editing negatively

Americans who are high in religious commitment – that is, those who attend religious services at least weekly, pray at least daily and say that religion is very important in their lives – are less inclined than those with either medium or low levels of religious commitment to say that gene editing is an appropriate use of medical technology.3 For example, those high in religious commitment are closely divided over whether it is appropriate to use gene editing to reduce a baby’s risk of disease later in life; 46% say this is appropriate, while 53% consider it taking technology too far. In contrast, roughly three-quarters of those low in religious commitment (73%) say gene editing to reduce a baby’s risk of developing a serious disease or condition is an appropriate use of medical technology. And, while a 57% majority of those high in religious commitment say gene editing to treat a congenital disorder in a baby is an appropriate use of medical technology, a much larger share of those with low religious commitment (82%) say this is appropriate.

Those with high levels of religiosity also stand out when considering the possibility that development of gene editing would entail testing on human embryos. An overwhelming majority of those high in religious commitment (87%) say this would be taking medical technology too far; just 11% of this group says this would be appropriate. In contrast, 55% of those low in religious commitment say that development of gene editing techniques that require testing on human embryos would be an appropriate use of medical technology.

The differences by religiosity in views on the appropriateness of gene editing tend to persist even when statistically controlling for other factors such as gender, race and ethnicity, age, and education that are related to religious beliefs and practices. See Appendix for details.

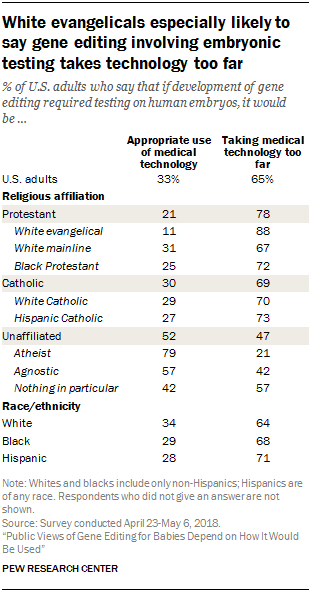

There are also differences in views about gene editing by religious affiliation, particularly if such techniques would involve embryonic testing. Just 11% of white evangelical Protestants say that if development of gene editing techniques required testing on human embryos, it would be an appropriate use of medical technology.

By contrast, about half of the religiously unaffiliated (52%), including 79% of atheists and 57% of agnostics, say that embryonic testing to develop gene editing techniques would be an appropriate use of medical technology.

See the Appendix for other views about gene editing by religious affiliation.

Men are more accepting than women of using gene editing to change a baby’s genetic makeup

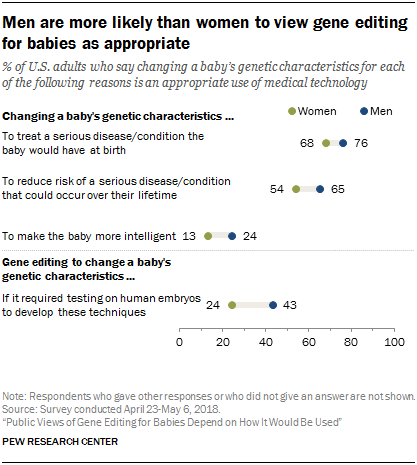

Men are more inclined than women to view gene editing as an appropriate use of medical technology, regardless of its intent. About two-thirds of men (65%) believe that gene editing to reduce a baby’s risk of developing a serious disease later in life is an appropriate use of medical technology, compared with 54% of women. And men (76%) are more supportive than women (68%) of using gene editing to treat a congenital disorder.

Similarly, more men (43%) than women (24%) are accepting of gene editing technology if it required embryonic testing to develop.

Women tend to have higher levels of religious commitment, on average, but differences by gender tend to hold even when controlling for religiosity and other factors in statistical models. See the Appendix for details.

Previous Pew Research Center surveys in 2016 and 2014, while not directly comparable due to different polling methods and question wording, have also found that women tend to be less accepting than men when it comes to gene editing for babies.

Americans with high levels of science knowledge are more likely to view gene editing in a positive light

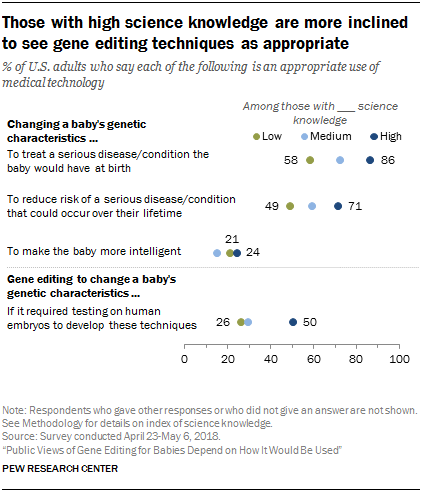

People high in science knowledge – based on a nine-item index – tend to be more accepting of using gene editing for babies.4 Some 86% of those with high science knowledge believe it is appropriate to use gene editing to treat a congenital disorder, compared with 58% of those with low science knowledge. And, 71% of those with high science knowledge say it is appropriate to use gene editing to reduce a baby’s risk of disease that would occur later in life, compared with 49% of those with low science knowledge.5

However, few Americans say it is appropriate to use gene editing to make a baby more intelligent, regardless of their level of science knowledge.

Judgments on the appropriateness of gene editing also follow a similar pattern by education level, which is closely linked with science knowledge. Those with a postgraduate degree are more accepting of gene editing for treating or reducing the risk of a disease than those with a high school degree or less.

Americans who report familiarity with gene editing are more inclined to see it as appropriate

People who say they have heard at least a little about gene editing that can be used to change a baby’s genetic characteristics are more likely than those who have heard nothing at all to say gene editing would be appropriate in each of the circumstances considered in this survey.

A Pew Research Center survey in 2016 found a similar tendency for those who report familiarity with gene editing to express more interest in and acceptance of using these technologies to enhance a baby’s health over the course of their lifetime.

Americans are more likely to anticipate negative than positive effects from gene editing

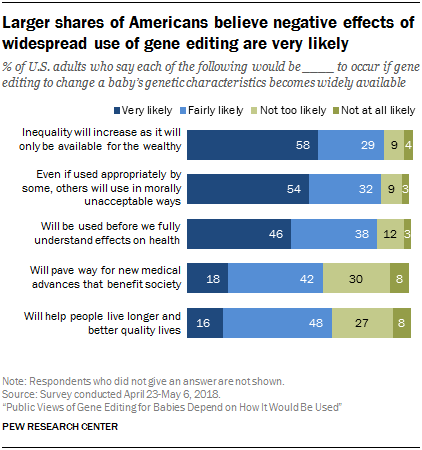

Although gene editing for babies is still in development, a separate April 2018 survey found that about half of Americans (52%) believe it is likely that within the next 50 years, we will be able to eliminate almost all birth defects by manipulating the genes of an embryo before a baby is born. In the current survey, as people think about a future with possible widespread use of gene editing to change a baby’s genetic makeup, more anticipate negative than positive effects on society.

Specifically, a majority of Americans (58%) believe gene editing will very likely lead to increased inequality because it will only be available to the wealthy. Some 54% of Americans anticipate a slippery slope, saying it’s very likely that “even if gene editing is used appropriately in some cases, others will use these techniques in ways that are morally unacceptable.” And, 46% expect it is very likely that gene editing techniques will be used before we fully understand how they affect people’s health.

Far smaller shares see positive outcomes as very likely if gene editing for babies were to become widely available. Roughly two-in-ten Americans (18%) say it is very likely that development of these techniques will pave the way for new medical advances that benefit society as a whole. Another 42% say this is fairly likely to occur, while 38% consider this not too or not at all likely. Just 16% see the widespread use of gene editing as very likely to help people live longer and better quality lives. About half (48%) say this is fairly likely, while 34% say this outcome is not too or not at all likely.

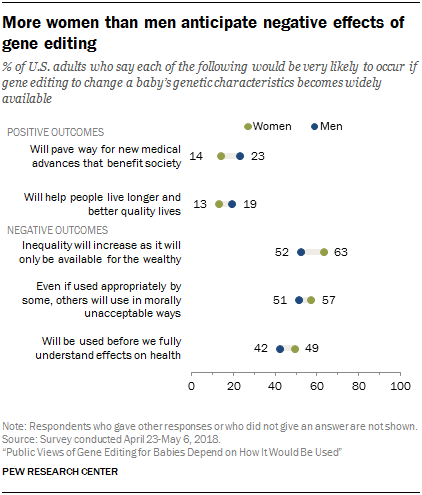

Women are more inclined than men to expect negative effects if gene editing becomes widely available, in keeping with gender differences over acceptance of gene editing. For example, larger shares of women than men say this technology will lead to an increase in inequality as it will only be available for the wealthy (63% say this is very likely vs. 52% of men) or say it will be used in morally unacceptable ways (57% vs. 51%). And although only minorities of men and women see positive effects as very likely, men are somewhat more inclined to anticipate positive outcomes.

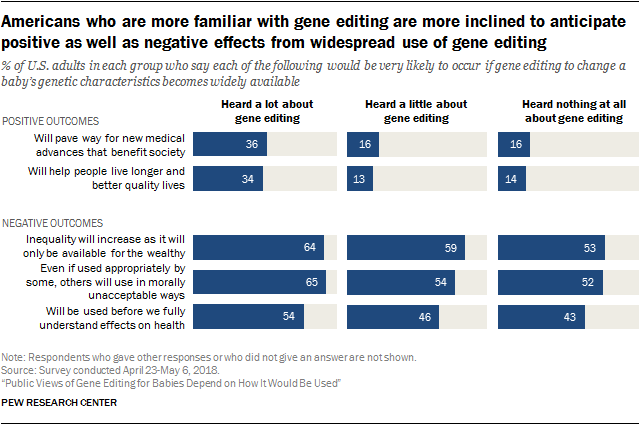

Expectations also vary by self-reported familiarity with gene editing. Those who have heard a lot about gene editing to change a baby’s genetic characteristics are more inclined to anticipate positive outcomes from its widespread use. Some 36% of this group thinks it is very likely that the widespread availability of gene editing would pave the way for new medical advances that are beneficial to society, compared with about half as many of those who have heard a little or nothing about gene editing (16%).

However, those most familiar with gene editing are more likely than those with no familiarity to also anticipate downsides. About two-thirds of those who have heard a lot about gene editing (64%) say it is very likely that widespread availability of gene editing will increase inequality because the technology will primarily be available only for the wealthy, compared with 53% of those who have heard nothing about using gene editing to change a baby’s genetic characteristics. And, 65% of those who have heard a lot about gene editing think it’s very likely that others will use these techniques in morally unacceptable ways, while 54% of those who have heard a little and 52% of those who have heard nothing about gene editing say this.

A similar pattern occurs with levels of science knowledge. A larger share of people with high science knowledge anticipate positive outcomes from the widespread availability of gene editing than those with low science knowledge. At the same time, those with high science knowledge are at least equally likely as those with low science knowledge to think negative effects from the widespread availability of gene editing are very likely.

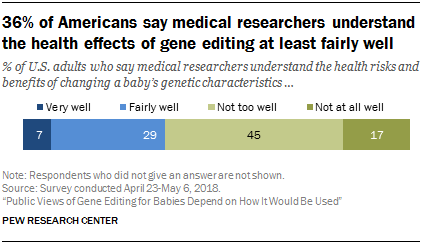

The American public also tends to be skeptical about whether medical experts fully comprehend the health consequences of gene editing. A 36% minority of Americans believe that medical researchers understand the health effects of gene editing for babies either very (7%) or fairly well (29%), while 62% say medical researchers do not understand the health effects at all or not too well.

Familiarity with gene editing is linked with beliefs about medical researchers’ understanding of it. About half of those who have heard a lot about gene editing for babies (51%) say that medical researchers understand the health effects of gene editing for babies at least fairly well, compared with three-in-ten of those who have heard nothing at all (30%). However, level of science knowledge based on a nine-item index is not related to views on this issue; 36% of those with high science knowledge and 40% of those with low science knowledge believe that medical researchers understand the health effects of changing a baby’s genetic characteristics at least fairly well.

There are no or only modest differences on this question by gender or religious commitment.