How was local television news changed by September 11 – the moment American foreign policy and the specter of terrorism became a local story?

Not even the attack on America and the war on terrorism could wrench local TV news from “live, local and late-breaking” coverage of carnage, crime and accidents.

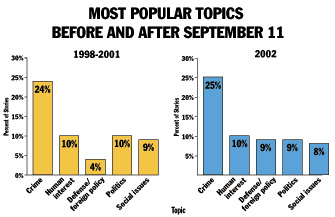

Local newscasts did begin to cover more of the world in 2002, but only a little more. And to make room for that coverage of defense and foreign affairs, local TV chipped away at the coverage of everything but crime and disaster. In the 2002 local TV news study, a quarter (26 percent) of all stories were devoted to crime, law and the courts, the most of any single year since 1998, when we began monitoring local television news.

The events and aftermath of September 11 did force local TV stations to become more international. Over the first four years of the study, foreign affairs and defense amounted to just 4 percent of stories. This year, coverage of those topics more than doubled to 9 percent, making it the third-most-reported subject.

Yet that figure may overstate how much local TV news really changed. Half of our study occurred in early March, during the heaviest fighting of the Afghanistan war. That week, coverage of the terrorism war at home and abroad swelled to 8 percent of all stories. In late April-early May, the second week of the study, coverage of the war on terrorism had dropped to 2 percent of all stories.

Most of this coverage, moreover, consisted largely of cut-and-paste stories from satellite feed footage (97 percent), rather than using local expertise to connect these issues to the community.

This is predictable with regard to the war abroad, given Pentagon restrictions and financial pressures. But one might have expected stations to staff the domestic war on terrorism, especially given local TV’s reliance on the public safety community for news.

Instead, when it came to the war at home – from airport baggage checks to the threat of bioterrorism – stations did relatively little reporting (just 1 percent of the stories), and hardly any of that involved much enterprise. Only 12 percent of all stories about homeland security were based on what would generally be considered enterprise reporting. The rest was coverage of “threats” picked up from police and fire scanners, news conferences, daybooks, or official press releases.

Indeed, there was as much coverage of missing children, especially the Florida disappearance of Rilya Wilson, as there was of local homeland defense (1 percent each) – and this was before the media glare focused on missing children in July and August.

What didn’t get on the air was notable. Issues directly affecting the lives of huge numbers of viewers got even less attention than usual. Some topics became almost extinct, including education and transportation issues (2 percent each). Consider a few statistics from the 7,423 stories we studied in 2002:

- Only nine stories about aging and Social Security.

- Thirteen stories about welfare and poverty.

- Fifteen stories about the arts.

- Thirty-three stories about race.

Coverage of social issues was down from the average of the first four years, as was the percentage of stories about civilization and culture. Despite a languishing economy, a moribund stock market, and a series of accounting scandals that rocked public confidence, economic/business news fell to the lowest level in the study’s history: to 7 percent of stories.

Stories about the job market, perhaps reflecting the scores of layoff announcements, increased, but still amounted to just 1 percent of the total. Put another way, coverage of the effects of the recession rose while coverage of the causes declined.

Reporting on politics, government and public policy (9 percent) did not increase, despite the political dimension of the war on terrorism. Consumer and health news held at 6 percent of all stories even though health reports and consumer recalls were the top two topics in which stations exhibited enterprise.

Much of the enterprise work is done by reporters assigned to specific beats. According to our survey of news directors, three-quarters of local newsrooms have assigned beats. Among those beats, medicine/health reporters were most common (42 percent) followed by crime or court beats (38 percent), education (37 percent), investigative (25 percent), consumer news (24 percent), and government/politics (24 percent).

With all those beats, why are newscasts still so full of crime news? Apparently the reflex to cover the “live, local and late-breaking” – usually crime – is so strong that it commands most newsroom resources not specifically earmarked for other subjects.

Indeed, the actions of cops, criminals, suspects, crime victims, family members, and lawyers made up 27 percent of all stories.

And nothing was on for very long. More than two-thirds (67 percent) of the stories ran a minute or less, 40 percent thirty seconds or less.

Television at its best can take us to places we cannot go ourselves, be it the corridors of power or the mountains of Afghanistan, and it can connect those places to our lives. But local TV news continues instead to be a surrogate rubbernecker, taking us to crime scenes, murder trials, and traffic accidents, where we can do little but gawk.

Not even a generation-defining event like September 11 has changed that.

Wally Dean is director of broadcast training for the Committee of Concerned Journalists. Lee Ann Brady is senior project director at Princeton Survey Research Associates.